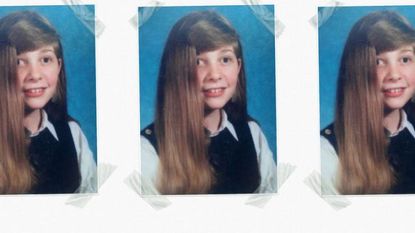

Are you sure that's how you want your hair?" the photographer asked. His tone was weary and judgmental. I must have been at least the 300th kid he'd photographed that day.

I reached up to my face to make sure that my curtain of tresses was falling right where I wanted it, exactly as I'd practiced placing it every day for months: directly covering my right eye, the lazy one.

"I'm sure!" I said with uncharacteristic confidence.

The photographer shrugged and snapped the photo. I marched back to eighth grade English class with my head held high, experiencing a rare moment of triumph in a junior high journey riddled with defeat. I smiled to myself. I had done it. In a pre-Photoshop world, I'd miraculously found a way to hide my greatest physical flaw from the unforgiving camera lens. All I'd needed was a little creative hairstyling and a full submission to my shame.

Year after year I did my best to look pretty for that dreaded class picture, and year after year a big glossy photo envelope was slapped down on my desk with rows of untamable, recalcitrant eyeballs staring back at me through the cellophane window, reproduced in a merciless series of 3x5s, 5x7s, and that one massive, horrific 8x10. Even my painstakingly-placed cascade of hair didn't do the one thing I so desperately needed it to: make me look normal.

I hated my lazy eye. It was the first and only thing anyone ever noticed about me. I could have gone to school every day dressed as a mermaid, and I still would have been the mermaid with the lazy eye.

Just a few of the things, in addition to the aforementioned hair curtain, I tried in order to hide it: I wore sunglasses even on rainy days. I covered it with my hand and then said I was relieving the pressure of my "behind-the-eye headache." Sometimes I just walked around with one eye shut, claiming an allergic reaction. Other times, I tried to line up the lazy eye with other people's gazes by sitting as far to the left of them as possible, turning my head away, and then focusing my good eye somewhere over their left shoulder. Nothing worked.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

RELATED STORY

Picking at My Face Almost Ruined My Life

"Why don't you get that thing fixed?" one of my classmates said to me during 7th grade Civics. "I had a lazy eye when I was little and my parents got me surgery to fix it. Your parents are abusing you."

I'd actually had surgeries already—two of them when I was just 2 years old. Both went horribly wrong and made my eye look significantly worse than it had in the first place. My mother was so horrified and heartbroken that she swore she'd never let me go under the knife again. Her solution was to just keep repeating this, over and over and over: "You are the most beautiful girl in the world. You look perfect just the way you are."

Years of ridicule and humiliation—plus therapy for anxiety and depression—followed. As a young woman, I became determined to do whatever I had to do to change my fate. To stem the tide of grimacing boys. To prevent people from thinking my lazy eye indicated a decreased mental capacity and that they had to talk to me slowly using small words.

I had three more eye surgeries over the next three years. The doctor told me that my eye would never be completely straight and that there was nothing he could do about the fact that I could only see out of one eye at a time. I'd still never be able to see a movie in 3D. I was still doomed to a life of parking two-feet away from the curb and missing the trash can whenever I tried to make a basket with a crumpled-up piece of paper. Glasses and contacts would be no help. But I didn't care about any of that. I would look normal.

The surgeries—during which doctors cut open my eyeball in search of the "lost muscle" that slipped away over a decade before—did help straighten me out. At 16, I transferred to a new school where I didn't carry the lazy-eye stigma of my past. I got a glimpse at what it was like to be someone other than "the girl with the lazy eye." I got a boyfriend. I made the cheerleading squad. I took photos in which I didn't look like Cousin It.

Still, I remained obsessed with the idea that I'd quickly become the outcast again if anyone found out my secret. Occasionally—especially if I was tired or stressed out—my eye would drift and the person I was talking to would innocently look over their shoulder, turn back, and ask, "Are you talking to me?"

RELATED STORY

Here's the Brutally Honest Reason I Went Blonde

I was terrified I'd be exposed. I started avoiding eye contact all together. One night at group therapy, another girl called me out:

"I have something to talk about that's been bothering me for a long time," she announced, proud of her commitment to the therapeutic process. "Liz never looks at me when she's talking to me or when I'm talking to her. I think it's rude."

I lifted my eyes from the floor and looked at her for just a moment. "I have a lazy eye," I said. "Sometimes people can't tell when I'm looking at them, so I just look at the floor." She was mortified. The flood of apologies that followed was even worse than the day in second grade when a kid held up the googly-eyed snowman he'd made and told me: "It looks like you."

But the truth was no one really noticed my lazy eye anymore, and that completely threw me. I started calling attention to it at every opportunity. "Sorry if it looks like I'm not looking at you guys when I talk to you," I'd say in my college study group. "I have a lazy eye." The response was always a series of shrugs and confused looks or someone saying: "Really? I can't tell." It started to piss me off. Suddenly no one seemed to notice or care about what I had come to believe was the one and only unique and important thing about me.

I kept identifying as cosmetically disabled because I was 100% sure it was the only thing that made me special. I had no idea who else I was. I switched majors five times. I joined the college improv comedy troupe. I went to lesbian night clubs wearing a sequined rainbow tube top to support my newly "out" best friend even though I was straight. I needed to be something.

The rest of the world was willing to look beyond my once-lazy eye, but I couldn't let them.

I met my second-ever boyfriend (and future husband) at a bar and became immediately suspicious when he called to ask me out the next day. When he showed up for the second date with flowers, I was sure he was a serial killer.

"What's wrong with him?" I asked my best friend. "He's handsome and smart. Why would he bring flowers to someone with a lazy eye? Do you think he has a creepy fetish for physically deformed women?"

I confronted him a few weeks later. "Are you pity-dating me?" I asked. "Because of the lazy eye?"

"You have a lazy eye?" he responded. "I didn't notice. I have this weird scar on my chin, so I guess we're even."

I was the only one who cared about my lazy eye anymore. I'd spent my entire childhood desperately wishing people would notice something else about me, and then, when it actually happened, I was too fixated on it to accept that.

Now in my 30s, I've finally embraced that I am more than my lazy eye. I'm a writer, a wife, a mother, and a failed commercial actress. Four years of auditions, and not a single booking. But honestly? It's kind of nice to be rejected for all the mysterious reasons everyone else is, instead of the obvious reason I always was.

Follow Marie Claire on Facebook for the latest celeb news, beauty tips, fascinating reads, livestream video, and more.

-

Meghan Markle’s New Netflix Cookery Show Begins Filming Today—But Not Where You’d Expect It to Be Shot

Meghan Markle’s New Netflix Cookery Show Begins Filming Today—But Not Where You’d Expect It to Be ShotThe Sussexes are having a busy week this week, shooting both of their his-and-her Netflix shows and rolling out the first product offering for Meghan’s new lifestyle brand American Riviera Orchard.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

How I'm Redefining My Wellness Journey in 2024

How I'm Redefining My Wellness Journey in 2024Sponsor Content Created With The Honey Pot

By Aniyah Morinia Published

-

Meghan Markle’s Lifestyle Brand American Riviera Orchard Reveals Its First Product Offering

Meghan Markle’s Lifestyle Brand American Riviera Orchard Reveals Its First Product OfferingFifty samples were sent out in the company’s first limited edition run of the item.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

The 32 Best Hair Growth Shampoos of 2024, According to Experts

The 32 Best Hair Growth Shampoos of 2024, According to ExpertsRapunzel hair, coming right up.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

The 20 Best Hair Masks for Damaged Hair, According to Experts and Editors

The 20 Best Hair Masks for Damaged Hair, According to Experts and EditorsHealthy strands, here we come!

By Gabrielle Ulubay Last updated

-

How Often You Should Wash Your Hair, According To Experts

How Often You Should Wash Your Hair, According To ExpertsKeep it fresh, my friends.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

The 11 Best Magnetic Lashes of 2023

The 11 Best Magnetic Lashes of 2023Go ahead and kiss your messy lash glue goodbye.

By Hana Hong Published

-

Beauty Advent Calendars Make the Perfect Holiday Gift

Beauty Advent Calendars Make the Perfect Holiday GiftThe gift that keeps on giving.

By Julia Marzovilla Last updated

-

The 18 Best Natural Hair Products in 2023

The 18 Best Natural Hair Products in 2023Remember: Your curls are your crown.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

The 9 Best Hot Rollers for the Curls of Your Dreams

The 9 Best Hot Rollers for the Curls of Your DreamsThis is how we roll.

By Samantha Holender Published

-

The 12 Best Cream Eyeshadows, According to Makeup Artists

The 12 Best Cream Eyeshadows, According to Makeup ArtistsThe best part? They’re so easy to apply.

By Samantha Holender Published