Life Behind Bars

So, what's life really like on the inside of a federal women's prison? Marie Claire's Lea Goldman talked to Piper Kerman, author of the soon-to-be-released memoir Orange Is the New Black, about her 15-month sentence in lockup in Danbury, Connecticut.PLUS: Read an excerpt from Orange Is the New Black here.

MC: Tell us about that first night in prison. I think a lot of people imagine prison the same way — people screaming, violence in the corridors, basically, your worst nightmare.

PK: It's not quite like that, but it is terrifying, and there's very little information that you can get in advance, especially if you're a woman. Lots has been written about male facilities, but not so much for women. When I surrendered, I was literally kept waiting in the lobby of the prison facility for hours and hours. Then I sat in a holding cell for several hours. Then it took hours to be processed — that's a really scary experience because for the first time you're coming in contact with prison guards, who are scary people in general.

MC: What makes the guards so intimidating?

PK: They are super-brusque and treat you in an unhuman way. You don't have any sense of what's going to happen next. Let's say, for example, you're going into the hospital — you'd feel like you can ask questions. You might not always get satisfactory answers, but you'd at least feel like you could ask questions to know what's going to happen next. But you can't ask questions in prison. All you can do is stand there, keep your mouth shut, and follow orders. That's intimidating.

Two of the prison guards who processed me were men. One of them began to mock me, to mimic all of my answers to questions, which is, of course, incredibly weird. There are all sorts of simple ways that they let you know: We're in control and you are absolutely not.

MC: What can you bring in with you?

PK: You can't bring anything. They take everything, right down to your underpants.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

MC: What does the prison give you, in terms of amenities and supplies?

PK: As a federal prisoner, you are issued toilet paper, tampons, eight packets of laundry soap once a month, and food. You also get a uniform, sheets, towels, a laundry bag, shampoo, and a mini toothbrush. But toothpaste and body soap have to be purchased at the commissary. It was over a month before I could actually shop at the commissary because the paperwork took so long to clear. You have a prison bank account, so you never actually touch or handle money. It's all handled by computer.

MC: In your book, you talk about plum jobs and room assignments. So, not all prisoners are treated the same?

PK: There are definitely hierarchies. The longer I lived there, the more surprised I was by the level of influence that prisoners themselves have over how things play out, at least in the minimum-security facility I was in. Everybody is expected to have a job, which is where the hierarchies typically play out. The woman who ran the kitchen got a lot of perks, like any housing assignment she wanted. She still got to smoke her one cigarette a day, even after cigarettes were banned.

MC: Is there any sexual tension between the mostly male prison guards and the female prisoners?

PK: I would certainly say that sexual harassment is rampant. Every single year there are examples of prison guards or staff who are caught committing sexual abuse. I think that any relationship between a staffer and a prisoner, even if it's consensual, is abusive because the staffer just has so much power. A guard can have you locked up in solitary [confinement] — it's completely your word against theirs.

MC: You didn't share your own sexual history — the fact that you once had a lesbian relationship — with any of your fellow inmates. Why?

PK: I kind of figured that would create more problems than I needed. There wasn't anything to be gained, and a lot of hassle might have arisen out of it.

MC: At the time of your imprisonment, you were engaged to your current husband. How did you stay in touch? Did he visit you every weekend?

PK: He visited me every single weekend. There are four pay phones in the facility, and you're allowed to use them if you have enough money in your prison account. I probably talked to Larry several times a week on the phone, in 15-minute increments. And he trekked up to Connecticut every single weekend to see me. His commitment was absolutely incredible.

MC: Martha Stewart was convicted and sentenced at roughly the same time you were imprisoned. Ostensibly, she should have been assigned to your prison in Connecticut. Why do you think she wasn't? [She was ultimately sent to a facility in West Virginia.]

PK: I don't really know the real reason. The minimum-security camp in Danbury where I served time is really broken down. It floods every time that there's heavy rain. There's very little in the way of rehabilitative programming. My assumption is that the Bureau of Prisons didn't want a public figure like Martha Stewart to get a full taste of how degraded life can be for prisoners within the federal system, so they sent her to the best facility possible, which is in West Virginia.

MC: Just how bad was the Danbury facility?

PK: One of the bathrooms was constantly infested with insects. There was mold growing in the walls. I worked on a construction team, and one day, we had cut open a wall in a classroom to do repairs. The interior was completely coated in a terrifying thick black mold. That stuff is nasty and toxic.

MC: How about the food? In your book, you discuss what a serious ritual eating and preparing food is for inmates.

PK: I went to Smith College, which is a very fancy women's college. And, you know, it doesn't matter what kind of setting you're in, if it's dominated by women, there's going to be a lot of obsessing about food! You can buy peanut butter or pickled jalapeños, bananas or even avocados from the commissary. There were two small microwave ovens that were available to 200 prisoners. It was kind of amazing what some women were able to produce out of this microwave oven. I only learned how to make one thing, which was cheesecake.

MC: How do you make cheesecake in a prison microwave?

PK: You actually only need the microwave to make the crust. The nice thing about prison cheesecake is that all of the ingredients come from the commissary. All you really need is some Laughing Cow cheese, a container of nondairy creamer, and a little lemon juice. To make the crust you buy some graham cracker cookies, add little bit of margarine, and cook it in the microwave for a couple of minutes. Then you mix up the other ingredients and pour it into your graham cracker shell. The problem is that, of course, you need to chill it. My 'Bunkie' had a bucket that she had secreted away, and I could fill that up with ice and basically just put the thing on ice. That's basically how you make prison cheesecake.

MC: I won't lie — that sounds less than tempting.

PK: It tastes better than it sounds.

MC: When you were finally released, you write about how you raced into the arms of your fiancé, who was waiting for you outside a Chicago courthouse. What did you do that evening?

PK: He took me out for a really nice lunch before flying home to New York. It was so overwhelming to not wear a prison uniform, to be able to walk around freely.

MC: Was the adjustment to freedom difficult?

PK: I definitely had many moments in those first few months where I'd just be like, I can't believe I'm in a taxi, I can't believe I'm on the subway, I can't believe I'm sitting here in my living room.

MC: Are you back to work?

PK: I went back to work right away. I was very lucky — a friend of mine created a job for me at his company. Most prisoners who come home face really significant challenges when it comes to finding work. It's very, very hard for most people who have a criminal record to get a job. I think the system is very wasteful of taxpayers' dollars. It's also very wasteful of human potential. I found that most people whom I was locked up with were, you know, good people who have skills and value. Prison is a missed opportunity to nurture those things.

Read an excerpt from Piper Kerman's memoir Orange Is the New Black in the April issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now.

-

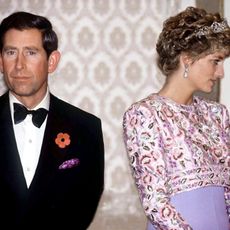

Princess Diana Revealed to a Royal Author the Real Reason Why Her Marriage to Prince Charles Ended Not Long Before She Died in 1997

Princess Diana Revealed to a Royal Author the Real Reason Why Her Marriage to Prince Charles Ended Not Long Before She Died in 1997And no, it apparently wasn’t Camilla Parker-Bowles.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Princess Martha Louise of Norway Sets Wedding Date with Fiancé Shaman Durek Verrett After a Two Year Engagement

Princess Martha Louise of Norway Sets Wedding Date with Fiancé Shaman Durek Verrett After a Two Year EngagementAlready billed as “one of the most beautiful high society weddings of the year,” the celebration will last for four days.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Heidi Gardner Opens Up About Viral Moment She Broke Character During ‘Saturday Night Live’ Beavis and Butt-Head Sketch

Heidi Gardner Opens Up About Viral Moment She Broke Character During ‘Saturday Night Live’ Beavis and Butt-Head Sketch“I just couldn’t prepare for what I saw.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

The Best Bollywood Movies of 2023 (So Far)

The Best Bollywood Movies of 2023 (So Far)Including one that just might fill the Riverdale-shaped hole in your heart.

By Andrea Park Published

-

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ 2023: Everything We Know

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ 2023: Everything We KnowCue up Mike Reno and Ann Wilson’s “Almost Paradise."

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

Who Is Gerry Turner, the ‘Golden Bachelor’?

Who Is Gerry Turner, the ‘Golden Bachelor’?The Indiana native is the first senior citizen to join Bachelor Nation.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

‘Virgin River’ Season 6: Everything We Know

‘Virgin River’ Season 6: Everything We KnowHere's everything we know on the upcoming episodes.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

The 60 Best Musical Movies of All Time

The 60 Best Musical Movies of All TimeAll the dance numbers! All the show tunes!

By Amanda Mitchell Last updated

-

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We KnowNetflix owes us answers after that ending.

By Zoe Guy Last updated

-

35 Nude Movies With Porn-Level Nudity

35 Nude Movies With Porn-Level NudityLots of steamy nudity ahead.

By Kayleigh Roberts Last updated

-

The Cast of 'The Crown' Season 5: Your Guide

The Cast of 'The Crown' Season 5: Your GuideThe Mountbatten-Windsors have been recast—again.

By Andrea Park Published