Seven years after a Goldschläger-wielding football player claimed my virginity, I wrote a law school term paper that ended with a plea: Victims of date rape should work together to alter their public perception and effect change. Then I lived my life and waited for someone else to do it.

Twelve years later, my call was answered when countless victims made their voices heard. I felt the weight of the Columbia student's mattress as she dragged it to class in protest, and Lena Dunham's rage when her partner removed his condom and flung it into a tree. I felt confusion and panic alongside the women who said they sipped a drink with Bill Cosby and awoke with no memory of what followed. Yet I also felt safe, shielded from their trauma by the distance between us, the comfortable gap between writer and reader, anchor and audience. These were their ghosts, not mine.

Then one Friday night, at a table for two at a restaurant in Manhattan's Upper East Side, I stopped being a safe, silent observer. Over chicken and pinot with my husband, I became the subject of the conversation.

"Can you educate me?" he asked, as my small sip of wine turned into a gulp. He didn't have to explain further; I knew he was talking about my ghost. He wanted a glimpse behind the curtain, a peek into the part of my past we'd discussed only once in our nearly six years together. "I need you to help me understand."

He had just returned from two college campuses where, as a Title IX attorney, he helped the schools investigate sexual assault allegations. The subject weighed on him, even more so given the recent Rolling Stone statement questioning its (later-debunked) reporting of an alleged gang rape at UVA. He craved insight that I am uniquely qualified to give.

But I didn't want to join the conversation or help him understand. I preferred to pore over articles and essays, sympathize and judge, and digest it all alone.

What's more, I couldn't help him understand that which I still don't.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

I fixated on the saltshaker and made broad statements like, "It's complicated," and, "It's often a gray area." I swallowed my chicken whole as his questions flew at me like darts, filling my mouth with food so there was no room left for words.

When he didn't relent, I explained that "the girl often likes the guy, and goes out with him willingly."

"Often, she drinks with him, willingly."

"Often she fools around with him—to a certain extent—willingly."

I shifted in my chair and told him vanilla facts that were a mystery to no one, withholding all personal flavor that could cause him to judge me. I wasn't brave like the women in the news; I felt scared and exposed, just like I had felt nearly two decades earlier.

I felt scared and exposed, just like I had felt nearly two decades earlier.

I didn't tell him that sometimes you are 17—just four days past the age of consent—and despite your book smarts, you are, at times, stupid. Your focus gets derailed by the boy who sometimes calls for phone chats and makeouts. Occasionally you round a few bases with him, but despite his allure, you diligently keep your virginity intact. He applauds your good morals and says you should stick to them.

He asks you to pick him up one night and walks out of his parents' house carrying a brown-bagged bottle of booze. For an hour, you drive without a destination, tasked with finding the venue for the night's entertainment. You feel stupid and young because you have no place to go. You tell him that you snuck your friend's boyfriend into your parents' house when he was too tired to drive, that he slept on the couch and no one knew he was there. You just want to impress the boy, but suddenly a plan is born and it feels beyond your control. You know you should drop him off and say good-bye, but you don't want the night to end yet.

You sneak him in the door and up the stairs, the plush carpet concealing the sound of two extra feet. He waits in your room with his Goldschläger while you run downstairs to say good night. You return and lock your door, then pull two shot glasses off your shelf. Alcohol helps you find a voice when you are too awkward or nervous to conjure your own. You don't yet know that it can also silence your voice entirely.

You drink a few rounds together, then one on your own. He encourages you to forge ahead while he sits one out. You do this once, at least, but twice, you think. Within 20 minutes, the 87-proof bottle is empty, more gold bits floating in your belly than in his.

The fooling around starts out fairly normal, until you're not in normal territory anymore. Until you're naked, and you don't remember getting there. Until you go from sober to smashed in a blink. Until you need to say words you have never uttered before.

"Promise me nothing will happen tonight."

You're slipping into darkness and in your lucid moments, you know it. You realize you're in dangerous territory and that in seconds or minutes, your conscious time will run out.

"Promise me you won't let anything happen tonight," you repeat; then you say it again and again.

You've never experienced intoxication so instantly debilitating. As the Goldschläger travels through your 120-pound body, you feel yourself spinning out of the world where your brain and your mouth and your body all work in unison.

Despite the promises made, you feel him starting to penetrate you as your waning consciousness is regained from the pain.

"Promise me nothing will happen," you stammer again, scared, as you try in vain to push his body a few inches higher than your own. Though you keep conveying your intentions, a different decision is being made for you. Each time he answers, "I promise," he continues trying to break it.

And then, in the final seconds before it all goes dark, you give up. You slide open the drawer to the nightstand that once belonged to your grandmother and reach for the only condom you have ever owned. Your friend dispensed them at a party after making off with a bagful from Family Planning. You brought one home, never imagining you'd use it, more fascinated by it as something you had yet to see in real life.

You hand it to him.

And then your world goes black.

Sometime between the drunken blackness and the morning light come the shaking sobs, and as you weep he says, "Fucking take me home right now," and, "You're really ugly when you cry."

Then, through your tears, you ask the question that will haunt you more than all the rest of it: "Did it happen more than once?" and the answer: "Yes—yes, OK? It happened more than once." And you will thereafter imagine yourself lying there like a corpse, no concept of what he's doing to you, no idea where a second condom came from. You assume there was none.

You weren't unclear and the boy wasn't confused. He chose to ignore you.

In the days that follow, you cry to your friends, cry in their cow barn, cry on the lacrosse field. A friend persuades you to talk to a sheriff, and the first one is young and kind and hands you tissues while you cry in an uncomfortable chair. He tells you to come back a few days later, and when you do, the nice man is gone. He is replaced by a mean, older sheriff who says, "It sounds pretty consensual to me" as he walks you to the glass doors without making eye contact. He doesn't understand. You weren't unclear and the boy wasn't confused. He chose to ignore you. You chose to protect yourself when it became clear that that was the only power you had left. You wonder if he would call it "consent" if you handed over your keys to a carjacker who was taking your Honda with or without your permission. You gave up the keys to protect your life. And even if he's right, where was the consent for the second act—or possibly the third?

People start to talk, and the look on your best friend's face as you tell him about the condom makes you want to throw up your insides. Even he is starting to doubt you.

For the first time, you have a real problem, not a kid problem. You made some choices that led to some things and you don't know how to exist in the world that followed. You no longer know how to make good choices. Or maybe you're afraid no one will listen when you do.

So you see the boy again, once or twice. You want to feel normal again. If what he did was OK, then seeing him should make things better. If it's not just a one-time tragic incident, then maybe it won't be a one-time tragic incident that defines the rest of your life. He starts to have sex with you again once. You are sober, but you don't know what's happening. You're lying in his parents' bed when he leaves and puts on a condom in another room. Before you know what he's doing, he's in again. Then he stops, and you don't know which part to feel worse about. Nor do you feel better or normal afterward. Now you loathe yourself.

Despite you willing it to be, your life is never normal again. Four years later, in your college apartment, a room full of girls share some variation of the same story. You realize that this happens a lot, and no one's life is ever normal again.

Seven years after it happened, you still struggle so much that you spend a year in law school writing that term paper. You study the 1995 penal code and identify every crime he might have committed, even with all the gray areas. Some things, you learn, were still black and white, had anyone cared to look. You identify ways that lawyers can help women like you—ideas that one day will seem naïve and impractical given the realities of the legal system—and you never follow through with any of them because you still want to hide under your covers and forget it.

And try as you will, you never do forget. Nearly 20 years later, you still wonder how things would be different if it never happened. Life is a choose-your-own-adventure book; every option available since that night is a direct result of the preceding decision. Choose to bring the king to your castle, turn to page 62. Choose to drop him off at his home, turn to page 80. Would you still be this cold, frigid, childless queen if you had chosen the other path?

Despite you willing it to be, your life is never normal again.

Sitting next to my kind, thoughtful husband, who hoped to gain more from me than a vanilla recitation of facts, I didn't say any of those things. Instead, I agreed to share a crème brûlée I had no stomach for and answered his questions with useless chatter. I told him it's a gray area. I told him it's complicated. I told him nothing. I opted to be a bad conversationalist rather than a wife he might be ashamed of.

Then 19 years and eight months after I felt the Goldschlager burn in my throat, I wiped my eyes when he wasn't looking, finished my dessert, and went home.

I crawled into my bed, a place that should be safer than any other, but for one night long ago, was not.

And in that bed, I felt the familiar shame of the last 20 years. I wondered why I couldn't share my story with the man who sees my ugliest parts and loves me regardless; why, two decades later, I still had no voice. I suppose I've never been comfortable with how gray my story is, my own inability to point to an unambiguous villain or victim. I have apprehension over how much I can trust my memories. I'm uneasy knowing I could throw on a suit and argue both sides of the case. Maybe I couldn't handle the thought of my husband's curious green eyes reflecting my own doubts and shame.

Maybe I didn't tell him because I'm really ugly when I cry.

Or maybe some damage runs so deep that I needed to leave it undisturbed, far below the surface, buried in its own little grave. Maybe I just wanted it to stay there and stop haunting me.

-

'Baby Reindeer' Is Netflix's Latest Viral Hit—Will It Get a Season 2?

'Baby Reindeer' Is Netflix's Latest Viral Hit—Will It Get a Season 2?The miniseries from Richard Gadd has a very definite ending.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

The Best Unisex Perfumes Were Made to Be Shared

The Best Unisex Perfumes Were Made to Be SharedYours, mine, and ours.

By Sophia Vilensky Published

-

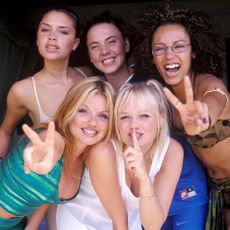

The Spice Girls’ Mini-Reunion at Victoria Beckham’s 50th Birthday Party Is a Precursor for a Forthcoming Tour, Sources Say

The Spice Girls’ Mini-Reunion at Victoria Beckham’s 50th Birthday Party Is a Precursor for a Forthcoming Tour, Sources Say“I’ll tell you what I want, what I really, really want”...is this to be true.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

The Best Bollywood Movies of 2023 (So Far)

The Best Bollywood Movies of 2023 (So Far)Including one that just might fill the Riverdale-shaped hole in your heart.

By Andrea Park Published

-

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ 2023: Everything We Know

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ 2023: Everything We KnowCue up Mike Reno and Ann Wilson’s “Almost Paradise."

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

Who Is Gerry Turner, the ‘Golden Bachelor’?

Who Is Gerry Turner, the ‘Golden Bachelor’?The Indiana native is the first senior citizen to join Bachelor Nation.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

‘Virgin River’ Season 6: Everything We Know

‘Virgin River’ Season 6: Everything We KnowHere's everything we know on the upcoming episodes.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

The 60 Best Musical Movies of All Time

The 60 Best Musical Movies of All TimeAll the dance numbers! All the show tunes!

By Amanda Mitchell Last updated

-

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We KnowNetflix owes us answers after that ending.

By Zoe Guy Last updated

-

35 Nude Movies With Porn-Level Nudity

35 Nude Movies With Porn-Level NudityLots of steamy nudity ahead.

By Kayleigh Roberts Last updated

-

The Cast of 'The Crown' Season 5: Your Guide

The Cast of 'The Crown' Season 5: Your GuideThe Mountbatten-Windsors have been recast—again.

By Andrea Park Published