There comes a time in every med student's life when she has to decide what she wants to specialize in—and for Dr. Varsha Jain, it was the specialty of all specialties: space gynecology. Since the first female astronaut launched into space in 1983, NASA has collected data about the effects of space travel on women's bodies, and Dr. Jain set out to put it to use.

Baylor's College of Medicine is home to the Center for Space Medicine, the only academic department of its kind in the world. Dr. Jain is a member of that staff, working closely with NASA, and she shared some fascinating info with us about how exactly an astronaut deals with her period, among other issues. Turns out those space women may have the right idea...

Marie Claire: Does space travel put women who are on contraceptives and period suppressors at risk?

Dr. Varsha Jain: Anybody taking the hormonal pill is at risk of developing clots. It's one of the biggest reasons women on Earth stop taking the pill.

NASA is very good at keeping a database of the astronauts before they fly, during the flight, and after they come back. And actually, my research shows that space flight doesn't seem to increase the risk of blood clots for women taking the hormonal pills. So even though there are some women astronauts taking these pills for a number of years on end (and this is similar to what many women do here on Earth), these women are so fit and healthy, because the selection criteria at NASA is so stringent, that going into space doesn't seem to increase their risk, which is great.

Marie Claire: How do female astronauts differ from other women?

VJ: The astronaut population is a group of extremely accomplished people, extremely intelligent. Astronauts have to work very hard to prove themselves. They are very motivated, very dedicated to their jobs. They're fit and healthy to the extreme, so it's not a population like you would see on Earth. Things like smoking, that increase the risk of clots, just doesn't apply to this group of people. They're geared to look after their health, which is different from most of the terrestrial population. Concerns like compliance with medication—forgetting to take tablets—isn't of concern with this group. The compliance comes into question with their training protocols. They're having to take multiple flights, several times a year, crossing multiple time zones. It's not the usual kinds of problems you'd encounter in a clinical practice. When you go into space, you're not measuring the number of hours until your next pill by the rising and setting of the sun but by the time on the clock (the sun rises and sets every 90 minutes as the spacecraft orbits the earth).

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Also, there are physical changes that happen when the human body goes into space. When these women are being recruited, the average age of an astronaut candidate finalist is about 32 years, and the average age of a female astronaut when she first flies is 38. There was a paper that was written a number of years ago that stated the average age of a female astronaut having her first baby was about 41 years. It's quite late, if you look at the general population. So keeping their reproductive organs healthy, if they do decide to have children after space travel, is important.

Marie Claire: What do astronauts use for birth control and period suppression?

VJ: At the moment, the gold standard is the oral contraceptive pill, taken back to back, continuously. From the terrestrial research and clinical use, we know you can do this for years on end, and it's not a problem for the female astronauts. The risks are actually the same as when they're taking the pill for 21 days and then having a break. This is what has been used predominantly by female astronauts and what appears to be current practice here on earth.

Marie Claire: Scientists once surmised that period blood would flow backwards, into the body, in space, though now we know that's not true at all. Does being a menstruating woman hurt your chances of becoming an astronaut?

VJ: There are very strict health criteria at NASA when people are selected to become astronauts. However, since menstruation is a completely normal process, it does not impact their ability to be selected. Because competition is so high, astronauts tend to end up being extremely fit and healthy people, who don't tend to have chronic illnesses.

Having said that, there are impacts from being in space. For example, one of the hot topics is a condition called VIIP [visual impairment due to intracranial pressure]. Basically, we're finding there are changes in the eye as a result of going into space, and we don't know why this is happening, or how. But as a result, it's changing the astronauts' vision. Interestingly, female astronauts don't appear to be showing sign of VIIP as much as their male colleagues.

The 2013 class, which was the last class recruited at NASA, was 50 percent female. It's extremely encouraging that women are becoming integrated into human space flight.

Follow Marie Claire on Instagram for the latest celeb news, pretty pics, funny stuff, and an insider POV.

-

Jennifer Lopez Goes All-White—$500,000 Birkin Included

Jennifer Lopez Goes All-White—$500,000 Birkin IncludedTwo things J.Lo loves? Monochromatic dressing and Birkin styling.

By India Roby Published

-

Zendaya Changes From Off-Duty Basics to Springtime Glam

Zendaya Changes From Off-Duty Basics to Springtime GlamThe actress packed three outfits into less than 24 hours.

By India Roby Published

-

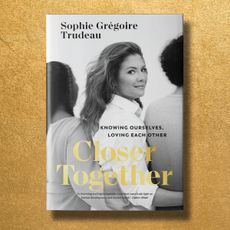

Sophie Grégoire Trudeau’s Next Chapter Is Still Being Written

Sophie Grégoire Trudeau’s Next Chapter Is Still Being WrittenHalf of a power couple for the last two decades, she’s learning through projects like her new book ‘Closer Together’ how to be more whole.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Bridgerton's Hair and Makeup Designer Reveals the Beauty Products Fit for Royalty

Bridgerton's Hair and Makeup Designer Reveals the Beauty Products Fit for RoyaltyErika Ökvist takes us behind the scenes of the Netflix hit.

By Faith Cummings Published

-

The Ultimate Gift Guide for 'Bridgerton' Lovers

The Ultimate Gift Guide for 'Bridgerton' LoversLive like you belong in the hit Netflix Regency-era romance romp.

By Maria Ricapito Published

-

12 New 2022 Memoirs to Add to Your TBR Pile

12 New 2022 Memoirs to Add to Your TBR PileFrom Kendra James's 'Admissions' to Viola Davis's 'Finding Me.'

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

Netflix’s ‘Maid’ Helped Me Open Up About Domestic Violence

Netflix’s ‘Maid’ Helped Me Open Up About Domestic ViolenceThe show is being praised for its portrayal of emotional abuse and other underrepresented forms of DV.

By Linsey Maughan Published

-

Julia Quinn's Bookshelves Are (Naturally) Filled With 'Bridgerton' Memorabilia

Julia Quinn's Bookshelves Are (Naturally) Filled With 'Bridgerton' MemorabiliaThe historical romance novelist gives us a peek of her home library in MC's 'Shelf Portrait' series.

By Marie Claire Published

-

Kim Kardashian West Insists She Divorced Kanye “For His Personality”

Kim Kardashian West Insists She Divorced Kanye “For His Personality”The mega-influencer's 'SNL' monologue was unexpectedly savage—and hilarious.

By Marie Claire Editors Published

-

10 Books to Read If You Love Watching the Olympics

10 Books to Read If You Love Watching the OlympicsThese stories revolve around the sports and competition we can't get enough of.

By Jessica Goodman Published

-

The Cast of 'Firefly Lane': Get to Know Who's Who

The Cast of 'Firefly Lane': Get to Know Who's WhoKatherine Heigl and Sarah Chalke lead the cast of the beloved Netflix dramedy.

By Andrea Park Last updated