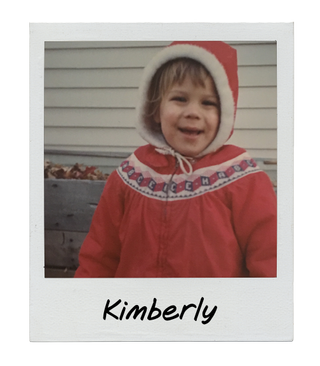

While her friends were shopping for cute bras and debating tampons versus pads, Kimberly Zieselman had yet to start her period. So at 15 years old, her parents insisted on taking her to the doctor. Eventually, a reproductive oncologist at Massachusetts General Hospital told her parents that their daughter's uterus and ovaries were only partially formed—and would likely soon become cancerous. The doctors pushed them to consent to a surgery to remove them, essentially a hysterectomy. She spent her 16th birthday that summer recuperating from the operation, but other scars wouldn't heal.

"On some level, I knew I was not being told the whole truth," Kimberly says. "But I was afraid to ask questions. I was the kid who did what I was told, who wanted to please adults and doctors. I sensed something awful was being hidden from me, and I didn't know who I could trust."

It wasn't until 26 years later that she learned the truth: She was intersex. Specifically, Kimberly has Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (AIS), one of more than 30 different intersex conditions. Externally, she looks typically female, but what the doctors removed, she later discovered, were internal testes. (She never had a uterus or ovaries at all.) These produced testosterone, which her body then converted to estrogen. In Kimberly's case, leaving the testes intact would have allowed her body to self-regulate and age without synthetic hormones.

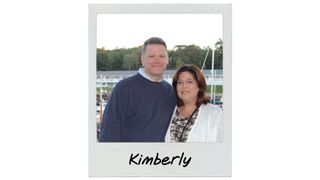

When she found out, Kimberly was 41 and a married mother of adopted twin girls living in the suburbs. "It was very disorienting," she says. "It took that foundation that your life is built on and pulled it out from under me."

While Kimberly felt her whole world was upended, her husband, Steven, was almost blasé when she told him. "He was like, 'Okay, it doesn't change anything,'" she says. Although she appreciated his understanding, she wanted him to recognize her turmoil. "I was confused and trying to figure out what it really did mean for me to have XY chromosomes."

It meant, essentially, that she's part of the thousands of people born each year with differences in their sex characteristics or differences of sex development (DSD). Usually, these variations occur before birth—in genes, chromosomes, genitals, body hair or reproductive organs. Widely accepted statistics put the number of intersex births at 1 in 1,500, but because there are more than 30 intersex conditions, some estimate it's more than 1 in 150 births.

"It's about 1.7% of the population, which is the same percentage of natural born redheads," says Kimberly, now the executive director of advocacy organization interACT: Advocates for Intersex Youth. "How many natural redheads do you know? That's probably how many intersex people you know. It's not that rare, just invisible."

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Kimberly learned the truth because she sought out her medical records after an adult hernia triggered painful memories of hernia surgeries as a child. Hernias are typical for kids with her intersex trait because their undescended testes push out. "On an unconscious level," she says, "I knew it was related, but it had been buried for so long."

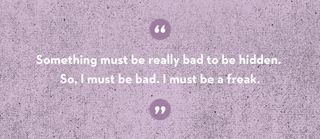

Her childhood surgeries, the unfounded threat of cancer and the sense of something secretive had left her traumatized. Her doctor diagnosed her with PTSD. "Even though I didn't know the truth, when you're a kid you know when there are things being hidden," she says. "Something must be really bad to be hidden. So I must be bad, I must be a freak." She had grappled with this feeling throughout childhood.

And although she didn't yet understand it was because of being intersex, Kimberly knew from age 15 that she wouldn't be able to have biological children. As a way of coping with her infertility, she had gone to law school and worked in the field of assisted reproductive technology. "I dealt with egg donor contracts, surrogate parents, in-vitro and other legal issues around family building in different ways," she says. "That was my way of subconsciously relating." After graduation, Kimberly married Steven, and they adopted twin girls from China.

Today, she has no regrets. "I'm so glad that this is the way I came to parenthood. This was definitely right for us," Kimberly says. "If I was told I could change things and take away my intersex variation, I absolutely wouldn't because of the path it's put me on, building the family that I've built and putting me in contact with so many amazing people through this community. It's really opened up my world. My focus now is on raising awareness and ending medically unnecessary, irreversible surgeries on intersex kids."

Trying to Forget Who I Am

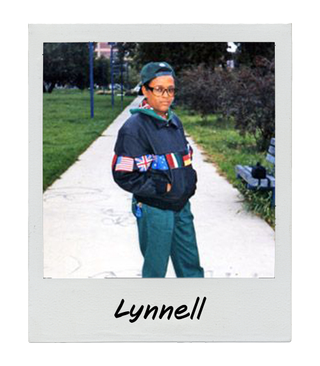

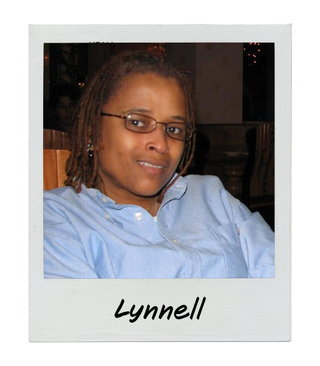

As Kimberly became more involved with other intersex people, she learned that she wasn't alone: Many had undergone surgeries that they didn't truly understand or were too young to give consent for. Some, like Lynnell Stephani Long, had serious lifelong repercussions from procedures performed in childhood.

Lynnell was born in 1963 on the south side of Chicago. At birth, she had the genes of a male, but both a penis and a vagina-like opening. At two days old, the doctors performed a genital surgery to make her conform to more "male" norms, and declared her a boy. She was raised as a boy named Steve by her mother. No one ever told her about the operation.

Starting at the age of 8, she was frequently admitted to the hospital for testing because she wasn't developing as quickly as other kids her age. And while her brothers were growing facial hair, she was growing breasts. She was diagnosed with growth hormone deficiency. "They never used the term 'intersex,' though, because that wasn't coined until 1996," says Lynnell, now 53.

In high school, locker rooms put her under embarrassing scrutiny, and male classmates would comment on her girlish looks or small penis. When she turned 14, doctors started her on hormone injections. "I didn't think it was helping me; I thought it was making me sick," she says.

Lynnell didn't know it at the time, but that's because she also has a form of androgen insensitivity syndrome. As a result, her body doesn't absorb male sex hormones, or androgens, which included testosterone. "I wasn't having any of the symptoms they thought I'd have after years of injecting myself with testosterone," she says. "That was very traumatizing."

To be fully male and "pick a side," Lynnell eventually married a woman. "I figured that maybe if I did, I'd be the guy to make my mother happy," she says. "It didn't work. I set my wife and I up for failure, because it's impossible for someone to make you something you're not."

The marriage only lasted a year. Lynnell spiraled into drugs and alcohol. "I was suicidal, not because of marriage but because of who I am," she says. "I felt that I was destined to live in between, not being one or the other ... I did a lot of crazy s*** trying to forget who I am, to not be me."

It wasn't until 1996 when she saw intersex advocate Cheryl Chase on television that the light came on. "I was never told I was intersex, I was just told that I needed extra help being a boy," she recalls. "But she's talking about symptoms, like being infertile. A light came on. My mom changed the channel but I turned it back."

After that, Lynnell tracked down her medical records, where she read about the surgery performed on her as an infant. She found an endocrinologist who diagnosed her intersex condition and put her on estrogen. "I finally fit the pieces of the puzzle together," she says. "It was eye opening. The grass was greener, the sky was bluer." She stayed sober. She changed her name too.

"I had to figure out who I really am," Lynnell says. "For me, I never felt male. I always felt like I didn't belong anywhere. I was a boy who played with dolls. Psychologically, what happened years ago did so much damage. I just wanted to be me. If I could exist without gender, that would be perfect. So my gender is intersex."

Changing Medicine for the Better

For decades, common treatments for intersex babies were based on a plan proposed by psychologist John Money in the 1960s. The belief was children should be protected from looking atypical—or even knowing they had been born different. Doctors were encouraged to perform genital surgery on babies and to discourage parents from talking about it with the child for fear of psychological trauma.

But ignorance wasn't bliss for many intersex children or adults. Genital surgeries carry huge risks. In many cases, they can result in lifelong pain, incontinence and loss of sensation, and many of these operations are performed on infants and children without their consent. Not surprisingly, many intersex people distrust the medical community.

On October 26, 1996, now celebrated as Intersex Awareness Day, a group of intersex activists protested against the way doctors were treating intersex babies outside the American Academy of Pediatrics conference. That marked the beginning of organized intersex advocacy and paved the way for a 2006 paper published in the journal Pediatrics and signed by 50 experts to consider a new way of managing intersex variations. The idea was that doctors should assign a child a gender after birth—based on their genes, internal organs and appearance—and should discourage parents from rushing into surgery. But it doesn't specifically tell doctors not to operate, either.

Today, doctors continue to gradually change how they treat intersex babies and adolescents. Instead of pushing for cosmetic surgeries to make babies look "normal" (or acquiescing when a parent wants one), many doctors wait to take action if a baby or teenager doesn't have any conditions that pose a health risk or other complication.

"We're trying to make sure a family has enough time to digest the information and make the best informed consent they can make when it's not an emergency," says Dr. Lynn Hunt, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on LGBT Health and Wellness. "All DSDs aren't the same, all human beings aren't the same, all families aren't the same. We need to work with the families to make them realize that they have a wonderful kid, but something just developed differently."

Parents need to consider the pros and cons of surgeries—and doctors shouldn't push, she adds. "Some surgeons talk about how little people heal better than bigger people, without scarring or without constriction. And there is a group intersex people for whom surgery might be an appropriate choice early on because of the need for fewer surgeries," Dr. Hunt says. "But the other half of surgeons say we don't have enough knowledge about for whom this is a good choice and for whom this is a terrible choice. If we don't know if there is definitely a good outcome, we should really hold off."

The social conversations about gender and orientation—while completely separate from intersex—are also helping advocates bring the issue to the spotlight and informing medical professionals. That's especially true when it comes to genital surgeries. "We're not always right," says Dr. Hunt of people like Lynnell, who were born ambiguous. "We've learned from our trans youth that we don't always make the right decision when people's genitalia are typical, and it's probably safe to say that when people's genitalia are atypical we have a higher incidence of not being right." And because some of the effects of intersex treatment can affect both mental and physical heath, she adds, doctors are beginning to be even more careful when treating intersex kids.

In 2015, the United Nations declared intersex surgeries without consent a human rights violation, comparing them to torture. But around the world, only a few places, like Australia and Malta, have passed legislation to specifically protect intersex people. In the United States, Ed Clere, a Republican member of the Indiana House of Representatives, proposed a bill in the state protecting intersex children in foster care. When the bill was put forward in January 2016, it didn't receive a hearing. Still, he continues to speak about intersex rights throughout Indiana.

"After the UN statement, I felt like the tide was turning, but little has changed," says Kimberly. "Unfortunately, despite some growing awareness and changes in the medical community, I'm still regularly hearing from parents who feel they were pushed into early surgery without having full information about the risks."

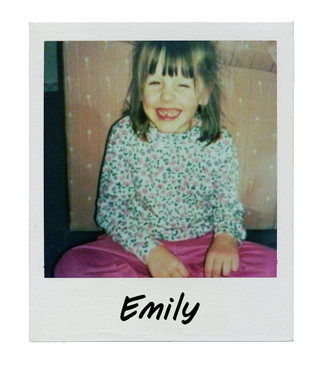

Because of the growing awareness, younger intersex people like Emily Quinn, 27, have come of age in a safer, more informed generation—though not without challenges of their own. Emily found out she had a form of Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome when she was only 10. Because she has several family members who have the condition, her mother knew it was a possibility, so she took Emily to the gynecologist. Afterward, Emily was told not to speak about it. "My mom had seen the way her sister had been bullied back in the 1960s, and she was worried about the same thing happening to me."

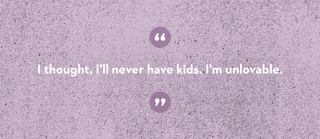

The challenges of dealing with this new knowledge were compounded by the family-focused community in Utah she grew up in. "Here, the self worth of a woman is based on whether or not they can have children," says Emily, who is also infertile. "You learn from an early age that you're going to get married and have kids. That was the hardest part for me. I thought, I'll never have kids. I'm unlovable. I'll never have anybody to be in a relationship with."

Unlike Kimberly, Emily didn't have surgery—despite the pressure from her doctors. "Because my testes were left intact, produces natural hormones and I don't have to go on hormone therapy," Emily says. "I know I'm really lucky."

Both Kimberly and Emily were also encouraged by their doctors to have a vaginoplasty to expand their vaginas. Fortunately, both of them were able to avoid that invasive surgery.

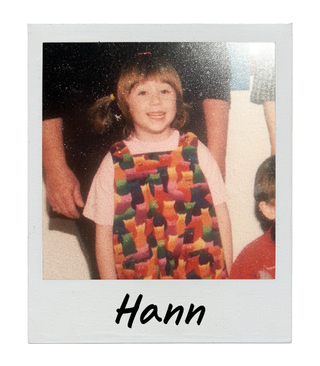

For Hann Lindahl, however, surgery was a good option. She found out she was intersex at 15, when, like many intersex people, puberty just didn't start. At age 16, Hann had surgery to remove her gonads, the tissue that becomes ovaries or testicles. In her case, they weren't producing hormones at all.

"That was the right choice, but that's very much an anomaly for intersex people," says Hann, 24. "One of the lies intersex people are told is that you have to have these removed otherwise it could become cancer. In my case, they just weren't doing anything for me. The important thing was that I was old enough to make that decision for myself."

Breaking the Silence

All four women found support networks of other intersex people, which has been an important part of their journeys. They share their stories publicly in an effort to end intersex stigma and unconsented surgeries—despite any potential backlash. For Lynnell, it was like "climbing a mountain" to talk about being intersex after the long process of coming to terms with it herself. "I felt like I was pulling the scab off these old wounds. It hurt—it hurt a lot," she says. "But I had always had a feeling that said, 'You need to do that. You need to do this to help the person who grew up like you.'"

Kimberly's 15-year-old daughters have been given bits of information gradually. "The first time we talked about it they were 9 or 10, around when I was explaining what puberty is and what's going to happen to their bodies, explaining it didn't happen to mine in the same way," she says. "Now, they're really proud of the work that I do, and they've told me stories of informing people—like their health teacher—what being intersex means."

Telling friends and romantic partners can also complicate relationships. Hann has received generally positive or curious responses from friends, which she says may be because many of them are on the LGBT spectrum: "They have had to think about things like this, had to have a deeper understanding of gender and sexuality and do that work for themselves." So far, she has only dated men and says she has been completely open with all of them and never gotten negative response.

But recently, Hann told a coworker she was intersex. "Their response was. 'Oh, I heard Lady Gaga was born with a tail. Is it anything like that?'" Hann recalls. "I was like, 'Yes, You hit the nail on the head.' It's just something that's not known about at all."

For Emily, her background means that infertility is a complex issue. "I'm still on the fence about kids, but for a long time, I told myself I didn't want them. And when I did online dating, I would only date people who didn't want kids, or who were on the fence about it or wanted to adopt," she says. It's difficult, she says, because it's not like getting married to someone and finding out later that she can't have children. She has confided in several partners, many of whom had positive responses. But one boyfriend ended up breaking up with her because she couldn't have children.

Publicly disclosing her story has helped with dating and friendships—in some ways. When MTV created an intersex character for the show "Faking It," Emily was consulted for the project. Later, she wrote a public letter "coming out" about being intersex herself. Since then, all a potential boyfriend has to do is Google her. So now she brings it up after a couple dates.

"When I was little, I looked things up online, which was scary," Emily says. "There weren't people talking positively about being intersex. But I knew that there couldn't be something wrong with me—I was born this way. That's a big reason why I do this. No one should feel like they're not lovable or accepted for who they are just because of the way they were born."

Follow Marie Claire on Facebook for the latest celeb news, beauty tips, fascinating reads, livestream video, and more.

From: Good Housekeeping US

-

21 Spring Essentials in Madewell, Banana Republic, and Shopbop's Flash Sales

21 Spring Essentials in Madewell, Banana Republic, and Shopbop's Flash SalesDon’t let these can’t-miss sales pass you by.

By Brooke Knappenberger Published

-

'Shōgun' Is a Masterpiece—Will There Be More Episodes?

'Shōgun' Is a Masterpiece—Will There Be More Episodes?With those ratings, never say never.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

32 Child Stars Who Have Aged Like Fine Wine

32 Child Stars Who Have Aged Like Fine WineThey made the notoriously bumpy transition to adulthood look easy.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Black Lives Matter Quotes That Are Powerful, Informative, and Necessary

Black Lives Matter Quotes That Are Powerful, Informative, and Necessary"Racism is a visceral experience...It dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth. You must never look away from this."

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Being Estranged From My Mom Is Hard. Mother’s Day Makes It Harder

Being Estranged From My Mom Is Hard. Mother’s Day Makes It HarderIt’s high time to start representing the different types of mother-daughter relationships—or lack thereof—that exist during the holiday.

By Christina Wyman Published

-

'Crying in H Mart' Is Our May Book Club Pick

'Crying in H Mart' Is Our May Book Club PickRead an excerpt from Michelle Zauner's memoir, here, then dive in with us throughout the month.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The 13 Best True Crime Books to Devour

The 13 Best True Crime Books to DevourThe definition of page-turners.

By Maria Ricapito Last updated

-

23 Black History Heroes You May Never Have Heard Of

23 Black History Heroes You May Never Have Heard OfThese are life stories worth knowing.

By Bianca Rodriguez Last updated

-

To End Sexual Abuse in Churches, Dismantle Purity Culture

To End Sexual Abuse in Churches, Dismantle Purity CultureThe Christian church’s norms provide the perfect cover for sexual predators—and leave their victims feeling like the sinners.

By Leslie Goldman Published

-

I Was Adopted by a Sex Offender

I Was Adopted by a Sex OffenderHow my stepfather's past changed my future.

By Sine Nomine Published

-

Where Did All My Girlfriends Go?

Where Did All My Girlfriends Go?Even in our hyperconnected world, true friendship remain elusive for young women looking to rebuild their college-era squads.

By Maggie Bullock Published