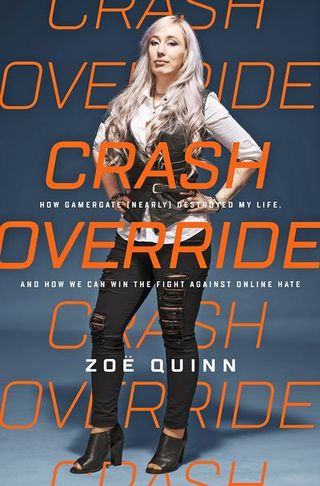

Zoë Quinn and I are part of a fairly exclusive club—one that's larger than it should be and growing all the time. In 2014, after the successful release of Quinn's game Depression Quest, her ex-boyfriend wrote a lengthy revenge blog post about his former relationship with her. When Quinn defended herself online, she was met with virulent trolls who published her private information, including her address, and barraged her with death and rape threats until, fearing for her own safety, she fled her home. The same thing happened to me after I, in my capacity as founder of Feminist Frequency—a website that analyzes the portrayal of women in pop culture—released a video examining sexist tropes in video games. In her book, Crash Override: How Gamergate (Nearly) Destroyed My Life, and How We Can Win the Fight Against Online Hate (PublicAffairs), out this month, the Los Angeles–based Quinn not only tells her own story of surviving threats of violence and online harassment, but also schools readers on Web culture and, most important, how to fix the problem.

RELATED STORIES

Anita Sarkeesian: We met briefly before Gamergate and became friends months later. I found a lot of healing in our conversations, because I knew that I could text you the twisted thoughts that come from being a survivor of trauma and you would understand.

Zoë Quinn: I completely agree. You get left with so many gross, dark things that are just put in your brain by external forces, and most people cannot handle it. There are few people I can talk to about the worst parts of what happened during Gamergate.

AS: People frequently approach me and say, "I've been harassed, but mine wasn't as bad as yours." I find it so disheartening; does this happen to you too?

ZQ: Yes, and it's such a weird thing to say. It's not a competition, and any harassment at all is too much—it doesn't matter if you've had a bad day or a bad forever. I feel like there's this growing commodification of suffering. If you are a marginalized person working in games, it's like, "Oh, I'm not a real game developer because I haven't been harassed yet." I've heard younger women say that, and I'm just like, "Noooooooo!" It's deeply upsetting. It's also horrible to see women who have been harassed and leave games say, "I wasn't strong enough." It's like, "No, you deserve better—it's not a sign of cowardice or weakness."

AS: When you're looking at all these horrible things written about you, you want to own your own story again—I hope this book does that for you.

ZQ: Me, too. At least now I'll have had the chance to say, "This is who I am—I'm Zoë Quinn, the person, not Zoë Quinn, the Google search term."

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

"At least now I'll have had the chance to say, 'This is who I am—I'm Zoë Quinn, the person, not Zoë Quinn, the Google search term.'"

AS: I think we're both in a place where we still don't own our stories, no matter how many years we've been talking about this. I'm still primarily asked to talk about harassment; I'm not asked to talk about the work I do.

ZQ: It's so frustrating that what happens to you overshadows what you did to overcome it. The number-one way to piss me off is to be like, "Well, at least the Gamergate trolls made you famous enough to get a book deal." No, they didn't—I did that! I worked my ass off, I kept going—they didn't give me a thing. When Gamergate started, everyone was like, "Just keep your head down, and it will pass." But I couldn't do that. I've taught girls in second grade how to make their first games. I can't say to them, "Yeah, come make games; it's great," and then when the shitheads are knocking on my door, act like this is someone else's problem. I have a sense of personal responsibility to the people I've taught how to make games—I can't just let harassment happen, because what about the next girl? There's going to be one.

AS: How did you formulate what you wanted to say in the book?

ZQ: I always want to find meaning in stuff that sucks—I don't want it to be the end of the sentence. It's like, "Yeah, that sucked, so what am I going to do with it?" When writing a book seemed like a possibility, I thought, If I'm going to do this, I have to have a very specific point. So I asked, "What can I take from this garbage that happened and how can I use it to make it less likely to happen to other people?" It was a lot to juggle—writing about this stuff in a way that was honest and gave it the emotional weight it should have without sounding melodramatic, because some of this stuff sounds like it was made up by space aliens.

AS: What can we do to fight against online harassment?

ZQ: The biggest and first thing is to get educated and stop downplaying the impact it can have on people's lives. A big barrier to people getting help with online harassment is the general attitude either that it's not a real issue—that it's "only" online—or that it's limited to someone saying they don't like you, and all of that stems from a basic misunderstanding of what we mean when we say "online harassment." I constantly hear from people who, before hearing my story, say they had no idea it was so bad or could consume someone's entire life and future. I think that once we improve the literacy surrounding the issue, it'll become easier to implement solutions and more likely that those solutions will be beneficial and carried out reliably.

Crash Override: How Gamergate (Nearly) Destroyed My Life, and How We Can Win the Fight Against Online Hate, $27

BUY IT: Amazon.com

AS: One thing I appreciate about your book is that, despite everything you've been through, you're not saying the internet is garbage.

ZQ: It's not. I would not have pretty much any of the good things in my life if it weren't for the Internet. I probably would not even be here, to be completely honest, without the support that my online community gives—it's like having a global family. I can't imagine my life without that. After all this, I'm still making games.

AS: What are you working on now?

ZQ: I'm making a comedy game. I decided to make this caring, goofy game about people loving each other and people loving themselves and being nice to each other and stuff like that. It's a comedy game about love, and that's a much better space to be in.

AS: Do you find working on the new game healing?

ZQ: Absolutely. There was a process to get to this point, though. For a while, I thought, I can't do this—I didn't want to deal with the repercussions. I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and started getting treatment. Now, I am very much looking forward to being in the space again. It feels like an arm that I'd fallen asleep wrong on: It's waking up, but it's still a bit numb and tingly, and I don't want to move it too much, but it's starting to feel right again. I don't know how people are going to react to the book or when this new game comes out this fall, but I'm hopeful. And it's nice to be hopeful for once.

This article appears in the October issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands September 19. Buy Crash Override: How Gamergate (Nearly) Destroyed My Life, and How We Can Win the Fight Against Online Hate on Amazon. Editor's Note: Anita Sarkeesian's company—Feminist Frequency—is the fiscal sponsor of Zoë Quinn's organization Crash Override Network.

-

Celebrate Earth Month With Our Feel-Good Fashion Report

Celebrate Earth Month With Our Feel-Good Fashion ReportYour guide to being more sustainable in 2024.

By Anneliese Henderson Published

-

Anne Hathaway Details the "Gross" Audition Request She Once Endured

Anne Hathaway Details the "Gross" Audition Request She Once Endured"Now we know better."

By Meghan De Maria Published

-

The Emotional Ending of 'Baby Reindeer,' Explained

The Emotional Ending of 'Baby Reindeer,' ExplainedNetflix's latest miniseries from Richard Gadd is based on the true story of the comedian and his stalker.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

48 Last-Minute Father's Day Gifts to Scoop Up

48 Last-Minute Father's Day Gifts to Scoop UpHe'll never even know you left it until now.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

16 Gifts Any Music Lover Will Be Obsessed With

16 Gifts Any Music Lover Will Be Obsessed WithAirPods beanies? Say less.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

This Pet Food Dispenser Is a Game-Changer for My Pet

This Pet Food Dispenser Is a Game-Changer for My PetThe futuristic-looking Petlibro Granary makes me feel so much less guilty being away from my dog.

By Cady Drell Published

-

The Privacy Whisperers

The Privacy WhisperersYou've read about their companies in the news. Now, hear from the women behind data privacy at the tech industry's heaviest hitters—Facebook, Apple, Google, and more.

By Colleen Leahey McKeegan Published

-

My Data Is Safe, Right?

My Data Is Safe, Right?There are two parts to the online safety conversation: privacy and security. Our quiz will help determine whether you're good to go on both fronts.

By Rachel Tobac Published

-

Who Are Myka & James Stauffer, Who Face Controversy After "Rehoming" Son Huxley?

Who Are Myka & James Stauffer, Who Face Controversy After "Rehoming" Son Huxley?YouTube star Myka Stauffer and her husband James are facing backlash for re-homing their young son, Huxley, who they adopted in 2017 and who has autism.

By Jenny Hollander Published

-

What Is "Houseparty," the App People Are Obsessed With In Quarantine?

What Is "Houseparty," the App People Are Obsessed With In Quarantine?It's the opposite of social isolation...without leaving your couch.

By Jenny Hollander Published

-

Group Video Chat Apps to Download While You're Social Distancing IRL

Group Video Chat Apps to Download While You're Social Distancing IRLWho's up for a virtual game night?

By Jenny Hollander Published