On a cold, gray August day in 2003, Victoria Donda, a 26-year-old law student, got a call from her friend Isaac. "We need to meet. It's urgent," he said. The petite Argentine was having a hellish week. Her father had tried to kill himself and now lay comatose with a self-inflicted gunshot wound. She had barely left his side since, even to shower or eat. Now, her head spinning from lack of sleep, her dark eyes swollen and red from crying, Victoria raced from the hospital to a nearby café to meet Isaac.

Earlier that week, the Argentine government had publicized allegations that her father, along with other ex-military officers, had taken part in Argentina's military dictatorship in the 1970s. He was accused of interrogating and torturing prisoners; he'd tried to commit suicide the night the news broke. Entering the café and sliding into a seat by the window, Victoria desperately hoped that Isaac, a friend from her volunteer work, would tell her the charges had been a huge mistake. Instead, he just looked at her, his eyes welling up behind his thick glasses.

"Negrita," he said, using a term of endearment for the black-haired Victoria, "you are the daughter of a couple murdered during the dictatorship. The people who raised you aren't your parents," he continued. She'd been kidnapped, and her identity had been changed at birth.

Victoria froze. She knew about the "children of the disappeared" — everyone in Argentina did. During the country's horrific military regime, from 1976 to 1983, thousands of ordinary people were killed, tortured, and "disappeared." The government claimed they were dangerous dissidents, but many of the victims were idealistic students and activists, and some of the women were pregnant. Their infants, delivered in jail, were stolen and given to conservative citizens who supported the dictatorship. These new "parents" raised the babies as their own. Now, 20 years after the end of the regime, humanitarian groups were trying to reunite the children of the disappeared with their biological families. At human-rights rallies, Victoria, a budding activist, had stood shoulder to shoulder with women whose pregnant daughters had been jailed. Distraught, decades later, these women were still searching for their grandchildren. She'd never dreamed she might be one of them.

Victoria grew up as Analía Azic, the daughter of Juan Antonio Azic, a retired coast guard officer turned grocer, and Esther Abrego, a housewife, in a middle-class suburb of Buenos Aires. An outspoken tomboy who was fiercely protective of her younger sister, Carla, and her sickly mother, Victoria was often sent home from Catholic school for talking back to the nuns. But her father never got angry: She was his "little princess." She loved spending the weekends selling apples and zucchini with him at his grocery store.

"I trusted my father like any daughter would, but we were especially close," she says now, sipping maté, a traditional South American tea, from a wooden gourd on the couch in her Buenos Aires apartment. Her mother, who loved to sew, made many of her clothes, including a favorite pink-and-white sundress. Victoria's childhood was idyllic.

By 26, she was studying law at the University of Buenos Aires, the path her father had chosen for her. Despite her father's conservative politics, Victoria was involved in liberal causes, spending hours volunteering in Buenos Aires' poorest slums and living in an abandoned bank building where she'd helped open a cultural center. Appalled that their daughter was barely eating and bathing in cold water, her parents bought her an electric heater and insisted she come home twice a week for dinner.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

One Thursday in late July 2003, when Victoria was home for a family meal, her father was uncharacteristically distant. She went to his bedroom to check on him and found him pacing, changing clothes distractedly. At 10 p.m., he left the house. Though her mother and sister went to bed, Victoria stayed up, watching TV. At 1 a.m., her father called and gave her a number, asking her to call in one hour. When she did, a stranger answered the phone.

"Your father is in the hospital," he said. "He just shot himself."

As she later learned, he had driven to the Buenos Aires clinic where her mother had spent months in treatment for pancreatitis, and sat down on a bench before a statue of the Virgin Stella Maris, patron saint of the naval forces. Her mother had prayed to that statue, offering a braid of her long blonde hair in exchange for recovery. Sitting before it, Victoria's father put a pistol into his mouth and pulled the trigger. The bullet had missed his brain but obliterated his nose, mouth, tongue, and jaw.

Victoria woke her sister and mother, and the family rushed to the Buenos Aires Naval Hospital where he'd been admitted. Bursting into her father's room, she gasped: He had no face. The bullet had left him disfigured and unconscious, but alive.

Reeling, Victoria fled her father's bedside and ran into the waiting room. Her first concern was for her mother, she remembers now. "I didn't cry. I just tried to explain to her what had happened." Then she saw her father's name in bright red headlines scrolling across the TV screen. Suddenly the suicide attempt made sense. He was on a list, issued by the Spanish government, of four dozen Argentine ex-military men accused of torturing and murdering civilians during the military regime. Argentina was roiling politically — the new president was trying to annul laws protecting the officers. The effort was controversial; years after the dictatorship, most of the men had resumed normal lives. Now Spain was demanding they face charges for human-rights crimes against Spanish citizens.

Victoria couldn't think straight. Her father's coast guard service wasn't something the family discussed — she'd never dreamed it was linked to the military or the country's decades-old dictatorship. Suddenly, the man she'd grown up with — who'd donated furniture to her causes and looked the other way when she'd come in past curfew — was accused of torturing and electrocuting prisoners. Survivors said he'd threatened to throw their children against the wall or electrocute them during interrogations. How could this be the person who, when she'd put a poster of her idol, Che Guevara, on her bedroom door, calmly asked her to at least move it out of sight? The idea was horrifying; she pushed it away.

"I couldn't deal with his name being up there," she says. "I remember thinking, I'm going to have to stop being an activist." But that didn't matter. His survival — and her family's — did. As her mother broke down in tears in the waiting room, Victoria decided she would move back home. Over the next few days, the women took turns spending hours at her father's bedside, going without sleep, hoping he would open his eyes.

At the same time, unbeknownst to Victoria, the news about her father had furthered a long-running, secret investigation into her past by human-rights workers. Throughout her childhood, questions had swirled around her identity. After she arrived home, in 1977, a neighbor — knowing the parents to be infertile, and connecting the dots with Victoria's "father's" ties to the military — tipped off a human-rights group.

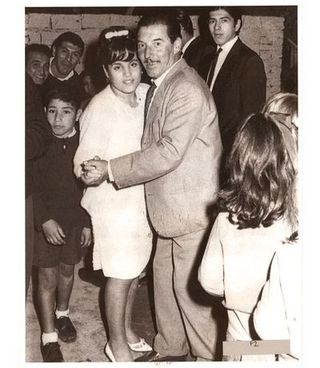

Meanwhile, a female prisoner who'd been present at Victoria's birth came forward. She described the labor, which took place in a filthy room inside the Naval Mechanics School, a notorious detention center — Victoria's mother had been in chains. Minutes after the birth, the new mother and the prisoner pierced the baby's ears with blue surgical thread. If she were released from prison one day, Victoria's mother hoped to use it to find her daughter in an orphanage. A baby with blue thread in her earlobes had later been seen by another witness in Buenos Aires. Ever since, rights workers had been investigating, interviewing friends and relatives of Victoria's birth family.

In late 2002, the rights workers set up a meeting with Victoria herself, posing as sociology students interested in her cultural center. They compared her appearance to pictures of her suspected biological parents, political activists who'd been disappeared in 1977. The resemblance was uncanny. Then, the week after Victoria's father's suicide attempt, they'd contacted Isaac through Argentina's human-rights community and told him what they believed: Analía Azic was actually Victoria Donda, who'd been seized from her mother's arms at just 15 days old.

Victoria remembers almost nothing from that first conversation with Isaac. "I wanted to erase it," she says. But one image remains: "The window was all steamed up. Isaac sat in front of me, crying, taking off his glasses and cleaning them with napkins."

Isaac said the rights workers who'd researched her case were waiting to speak to her. Calling her boyfriend for moral support, Victoria numbly trailed Isaac to another nearby café. The five women waiting at a small table were young, about Victoria's age; many of them also had disappeared family members. Their expressions were solemn, and they spoke softly, showing Victoria a copy of her birth certificate. It was signed by a military official, Dr. Jorge Luis Magnacco, who has since been accused of coordinating many of the baby kidnappings at the Naval Mechanics School. Her head spinning, she could barely articulate the question looming in her mind: "Who are my real parents?"

The only way to know for sure would be to take a DNA test, the women explained. After the dictatorship, parents of missing prisoners had volunteered blood, which had been analyzed, stored in a national database, and used to identify remains and reunite families. The woman sitting next to her, Vero, gently took her hand. "I hated all of them," says Victoria now. Getting up, she walked to the bathroom, shaking uncontrollably. Her boyfriend came in and wrapped her in his arms, not saying a word, but she couldn't stop trembling.

That night, Victoria returned to the home where she'd grown up, despondent. She couldn't fathom what she'd learned, let alone face the question of the blood test. Going into her parents' bedroom, she reached into the closet drawer where her father kept his service revolver. She took it out of its case and held it in her hand, feeling its weight, wondering if she should follow his lead. Was this the only way to end her nightmare? Then the consequences dawned on her. "If I killed myself, someone was going to have to clean up. I thought of the practical stuff," she says. Putting the gun away, she left the room.

For the next three months, she was ridden with indecision and anxiety. If she took the test, the couple who raised her might go to prison for kidnapping. But she couldn't imagine not discovering the identities of her real parents. Meanwhile, the life she'd always known had fallen apart. Guilt — and looks of pity — plagued her in public, so she scaled back her volunteering. She went to class but wore all black, burying the high heels she loved and her trademark low-cut, bright dresses and miniskirts deep in her closet.

In October, her father emerged from his coma. As he lay in bed over the next few days, she confronted him with questions. He still couldn't speak but scrawled answers on a notepad. "It was very emotional," says Victoria, who has sworn never to reveal what they talked about. He promised to support her if she took the genetic test, even if it would put him in jail — a promise her mother had also made. As she wrestled with the choice, she relied on friends, who took her calls at all hours, met her for teary conversations over coffee, and brought her to the dance clubs she used to love so she could feel normal again under the bright lights.

"I tried to forget what was going on," she says. "But I couldn't block it out."

In late 2003, Victoria visited Vero; the investigator had become a close friend. In Vero's library, Victoria found a thick book of grainy photographs of disappeared prisoners. She froze when she spotted a black-and-white image of a woman with dark eyes and full lips: María Hilda Pérez, or "Cori." She'd been abducted when she was five months pregnant.

Victoria couldn't take her gaze from Cori's eyes. "They were like mine," she says. "Turned down at the ends, with long eyelashes." Suddenly, her natural curiosity roared back to life, and she was desperate to know whether Cori was her mother. Still, she didn't take the test. Finally, on March 24, 2004 — more than a year after seeing the photo — she went to a memorial for victims of the dictatorship at the Naval Mechanics School, the first time she'd set foot in the place where her biological parents were held captive and she was born. She found herself next to a woman named Paula, who revealed that she was five months pregnant. It couldn't have been just a coincidence, Victoria thought.

"If Cori was my mother, then I was as little as the baby in Paula's belly when she was here," she says. "It must have been terrible. She was valiant. The least I could do was find out who she was." The next month, Victoria had blood drawn at a local clinic. Agonizingly, the results were never returned. On June 26, she got tested again.

Four months later, on October 8, 2004, a judge summoned her to a dank federal courtroom in downtown Buenos Aires and read the results. She and Vero wept on each other's shoulders.

"Your mother was María Hilda Pérez, known as Cori," he said. "She named you Victoria." It was the first time she'd heard her given name. "Your father was named José María Donda," the judge continued. "Now, what do you want to be called?"

"Victoria," she replied. But she kept the name she grew up with, and goes by Victoria Analía Donda today. "I am who I am in part because of how I was raised," she says.

Gradually, Victoria pieced together the story of her biological parents' lives, using a book of pictures and documents human-rights workers had given her. Her mother, Cori, she learned, had been a liberal activist, too. After falling madly in love with Victoria's father at university and marrying him in 1975, Cori was arrested, reportedly set up by her brother-in-law, Adolfo — Victoria's biological father's older brother, chief of operations at the Naval Mechanics School. Adolfo had long been mortified by his younger brother's left-wing politics.

Cori was captured at a train station where she'd been told to meet a fellow activist. Beaten and hooded, she was stuffed into a pickup truck. At a red light, she jumped out, sprinting until the high heels she was wearing snapped. In no time, her captors caught up to her. Victoria's father, learning of Cori's abduction later that day, found the shoes, discarded, by the station. He was jailed soon after. Victoria's parents saw each other for the last time in prison. Their captors brought her mother into her father's interrogation room to confirm his identity. They pretended not to know one another. Soon after giving birth — four months after her capture — Cori was drugged, loaded into a Fokker military airplane, and thrown alive into La Plata River, the fate of many of her fellow political prisoners. Her brother-in-law, Adolfo, was likely the one who approved her murder. José María's body was never found.

Victoria contacted her mother's side of the family, who'd since moved to Canada. But she resisted getting to know them, sure they would detest the people who'd raised her, whom she continued to love. Then, in March 2005, Cori's sister — Victoria's aunt — contacted her to tell her that Cori's mother, Leontina, Victoria's maternal grandmother, had Alzheimer's disease. Leontina had begged Adolfo (who is still alive and is now on trial for his crimes) for information about Cori in the years after her disappearance. Heartbroken at his stonewalling, she had moved to Toronto in 1987. Her remaining children, Victoria's aunts and uncles, had already made new lives there. Victoria decided to go to Canada to meet them the next month, in April.

The weeklong trip was bittersweet. "We were related, but they didn't really know me, and I didn't know them," Victoria says. She suspects she wasn't the granddaughter they'd expected: When they asked if she had a boyfriend, she answered, only half-jokingly, "Two." And when she told her grandmother she was an activist, Leontina exclaimed, "Oh, no! Another lefty!" with humor — and dismay. But Victoria hoarded every tidbit about her parents, asking obsessively what they were like, how they met, and what they ate. Her sassy mother had also loved to wear high heels. And like Victoria, Cori had had her father wrapped around her little finger.

Back home, overwhelmed, Victoria tried therapy, but what made her feel alive was community activism. She started volunteering again. Her life story had become so well-known by then that, in 2007, at 30, she ran for — and won — a congressional seat representing Buenos Aires. In 2009, she became president of the Human Rights Commission, which monitors the trials of accused repressors (including her "father").

Still, her family situation haunted her. In 2009, Esther, the woman who'd raised her, died. Their affectionate relationship had continued — Esther was never charged with kidnapping, thanks to the testimony of Victoria and her sister, Carla (who was later revealed to be the daughter of another disappeared couple). They told investigators Esther couldn't have been aware the adoption papers she'd signed changed their identities because she was illiterate at the time. (In fact, as a schoolgirl, Victoria had taught Esther to read and write.) Victoria says Esther believed Victoria was her father's daughter by another woman.

As for the man she grew up thinking was her father, Victoria visits him every two weeks, bringing cakes and medialunas, small Argentine croissants, to the secure ward where he is being held during his yearlong trial. He could spend the rest of his life in prison for the crimes of torturing and kidnapping; Victoria believes he should be punished. While she refers to him and Esther as her "appropriators" in public, she calls them mamá and papá in private.

"You can't turn love off like it's a faucet," she says. "He has to pay his debt to society. But I love him." Still, they don't talk about politics, she says, smiling. She believes he has repented for his crimes. His suicide attempt before the statue "was a way to ask for forgiveness from my mother, and from us."

The book that the rights workers gave Victoria on her biological parents is now tucked away in the wicker drawer of an end table in her living room, next to photos of the parents who raised her, articles about her family, and a purple cloisonné necklace from Leontina. She rarely goes through it anymore. "I've closed the stage of searching desperately to find my parents," she says. "I was looking for them in other people. Now I look for them in myself."

-

Kourtney Kardashian Barker Loves Her Postpartum Body, Thank You Very Much

Kourtney Kardashian Barker Loves Her Postpartum Body, Thank You Very MuchAfter a body shaming troll tried to tear her down, she reminded them that her body “gave me my 3 big babies and my little baby boy.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Clara Bow’s Great-Granddaughters React to Taylor Swift’s ’The Tortured Poets Department' Song Named After the Famous Actress

Clara Bow’s Great-Granddaughters React to Taylor Swift’s ’The Tortured Poets Department' Song Named After the Famous ActressThey “couldn’t believe” Swift named a song after the 1920s star.

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Here’s How to Get Out of a Speeding Ticket, According to Zendaya and Tom Holland

Here’s How to Get Out of a Speeding Ticket, According to Zendaya and Tom HollandUnfortunately, the rest of us might not be able to use this tactic.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Of Murder and Motherhood

Of Murder and MotherhoodTheir children are gone but these women are united in their fight for justice and answers.

By Katya Cengel Published

-

60 Gifts for Mom She'll Truly Love

60 Gifts for Mom She'll Truly LoveFrom creature comforts to luxe indulgences.

By Sara Holzman Published

-

'Skye Falling' Deserves a Spot on Your Summer Reading List

'Skye Falling' Deserves a Spot on Your Summer Reading ListIn July, Marie Claire read Mia McKenzie's 'Skye Falling.' See what the #ReadWithMC community thought about the book here.

By Marie Claire Published

-

Adria Biles, Simone Biles' Sister, Is a Former Gymnast and Simone's Biggest Fan

Adria Biles, Simone Biles' Sister, Is a Former Gymnast and Simone's Biggest FanSimone Biles' little sister, Adria Biles, is a fellow gymnast, a Simone lookalike, and a fierce champion of her famous sister.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Melissa Moore's 'Life After Happy Face' Podcast Looks at Killers Through New Eyes

Melissa Moore's 'Life After Happy Face' Podcast Looks at Killers Through New EyesThe true crime expert and daughter of the Happy Face Killer opens up to Marie Claire about destigmatizing the label of 'criminal's kid.'

By Maria Ricapito Published

-

Won't Call the Midwife

Won't Call the MidwifeWith high rates of maternal mortality and coercion in hospital settings, more American women are exploring childbirth without any medical assistance whatsoever. The Free Birth Society provides community, resources, and validation for these convention buckers. But experts warn that choice comes at the expense of safety.

By Rebecca Grant Published

-

Michelle Zauner's 'Crying in H Mart' Is Deeply Moving

Michelle Zauner's 'Crying in H Mart' Is Deeply Moving"She made me want to eat and cry at the same time..."

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

Being Estranged From My Mom Is Hard. Mother’s Day Makes It Harder

Being Estranged From My Mom Is Hard. Mother’s Day Makes It HarderIt’s high time to start representing the different types of mother-daughter relationships—or lack thereof—that exist during the holiday.

By Christina Wyman Published