In the middle of a small room, with dirty-white walls decorated with pictures of Jesus and an array of plastic plants, a young woman stands on a stool. She wears a cotton candy-pink ball gown. At her feet, three other women sew tiny flowers along the hem of her giant hoop skirt. Her lips are painted a circus- clown red; light brown curls frame her face. "A woman should always be beautiful," says Natalya Khapova, 26, as she poses on her pedestal. "Not just outside the fence. Even if she's in here, she should show her beauty. A woman is everything gentle and wonderful -- or she should be." The fence Khapova refers to surrounds the correctional facility UF 91/9, an all-women's prison camp some 20 miles away from the Siberian capital of Novosibirsk. Her ball gown is one of three outfits she will don for the prison's main event of the year: the annual "Miss Spring" beauty contest. As with most women at UF 91/9, the reason for Khapova's stay isn't entirely clear. At first, she says she was "just a witness" to an undisclosed crime. When pressed, she mutters that she was "an accomplice -- or something like that" in an assault and robbery charge. Khapova, who has six-and-a-half years left of her eight-year sentence, is one of more than 1000 female inmates serving time here for everything from drug possession to murder. Today, however, Khapova focuses on something decidedly more appealing than her long-term fate.

This annual pageant, which prisoners begin planning weeks in advance, bears little resemblance to, say, Miss America -- picture instead over-the-top costumes and makeup reminiscent of Cirque du Soleil, a static-filled stereo DJ-ing Russian pop music, and a cast of nervous contestants teetering dangerously in their borrowed stilettos. It's a welcome diversion from the monotony of life inside the jail, and a legitimate excuse for the prison staff to extend the women's curfew -- all the way to 2 a.m., rather than the usual 10 p.m. sharp. The contest also serves another purpose, as the winner's prize is neither money nor a modeling contract, but something far more precious: a ticket to freedom. "Early release" happens only by the recommendation of the prison staff to a special parole board. Foremost among the criteria for consideration is "active participation in the social life of the camp." Hence, the popularity of the Miss Spring contest.

Though more than a decade has passed since the fall of communism in Russia, a vast divide still exists between those reaping the rewards of a capitalist market and those who previously relied on government subsidies and now live in poverty. The economic turmoil has hit women hardest: During the 1990s, 7.6 million jobs held by women (largely "state" positions) were eliminated--one in every five female held jobs. (For men, job cuts affected one in every 100.) In fact, out of the 5.5 million registered unemployed people in Russia, about 70 percent are women, according to the International Labour Organization. Coinciding with this rise in unemployment, the percentage of women committing crimes has also increased. From 1992 to 2004, the number convicted almost doubled, from 193,000 to 376,000 -- although only about a quarter of these women actually do hard time. Their crimes are exacerbated by a drinking and drug epidemic sweeping the country. Alcoholism, of course, is a longstanding tradition in Russia, where the average person consumes more than 17 liters of pure alcohol every year. But the narcotics trade is relatively new. Fueled by more open borders and the new elite's growing disposable income, Russia's drug business has grown into a $15 billion-a-year enterprise. The official number of drug addicts in Russia has risen 15- fold in the last decade to half a million, although experts think the true number is significantly higher. "Experts believe the total could be between 3.5 million and 4 million people," says Valentin Bo by rev, deputy chief of the parliamentary security committee. "The rising tide of drugs has triggered an increase in the number of drug related crimes." Half of the women at UF 91/9 are doing time for narcotics.

CREATIVE THERAPY

Amid these bleak realities, hundreds of women find themselves calling UF 91/9 home every year. Few sources of convict entertainment exist in Siberia, where temperatures in the winter can drop to -40 degrees. "We wanted to find ways to occupy convicts' free time," says Natalya Baulina, the prison's school marmish administrative head. "This contest gives prisoners an opportunity to feel like women, to dress up, put on makeup, and imagine they're connected to Russia's new freedom. "When I first introduced the idea to the women, they were in utter shock," Baulina adds. "The only pageant they knew was Miss Universe--women parading in barely visible swimsuits before male judges. They asked, 'How do you imagine we are going to do that?' I replied, 'We'll invent our own rules.'" The rules include each of the prison's nine sections picking one inmate to represent it, then creating costumes for three categories: "Greek Goddesses," "Flower Gowns," and "Imaginary Uniforms," for which inmates design their ideal prison uniforms of the future. Although the women admit that they'd never heard of many of the Greek myths or exotic flowers they will portray onstage, they are learning fast from books provided by the staff.

When the contest first began five years ago, supplies were nonexistent--the winner made her dress out of plastic bags from the prison kitchen. Even today, the women make use of whatever they can get their hands on, including pieces of the plastic plants that hang throughout the facility. Several guards and unit chiefs serve as judges, crowning the winner "Miss Spring" and two runners-up "Miss Charm" and "Miss Grace." A tiara will adorn Miss Spring; all three receive yellow sashes to drape across their costumes and goody bags filled with makeup donated by prison staff. In its brief history, the contest has gained a bit of notoriety; news crews now broadcast the event on local TV, inspiring other Russian prisons to host similar contests and fueling a debate between the media (it's good for ratings) and prisoners'-rights activists (the contest exploits the women). For the inmates, it's just another way to pass the time. Yulia Lutzkhak, 30, is serving four years for selling three grams of heroin. It was about 10 years ago that Lutzkhak's life unraveled: A miscarriage, a cheating husband, and unemployment led her into drug use. "I was on opium for three years, then heroin for a year," she admits. "I didn't have enough money, and someone asked me, Why don't you sell some? That's how I wound up here." Lutzkhak's sentence is up next April, and she's already planning for her new life on the outside. "I want to take computer courses," she says, "and then maybe work at an orphanage." She never wants to come back to UF 91/9, but she worries about the likelihood of finding work and the temptation to sink back into her old ways.

There is no program in place to help Lutzkhak transition back into society, although the government recently created its first-ever large-scale anti-drug campaign. Now, ads for special hot hotlines are springing up along the streets of Novosibirsk. The best thing to do, hotline experts advise, is check into a private clinic for treatment with "special medicines" (usually methadone, the heroin substitute). However, the cost of the clinics--starting at around $2000--prevents women like Lutzkhak from ever setting foot inside.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

LIFE ON THE INSIDE

There are hundreds of stories like Lutzkhak's at UF 91/9. A man is almost always involved, either cajoling his partner into drug-related crimes, or abandoning her so that she needs to make a fast buck on her own. Almost all women cling to the hope that someone on the outside is waiting for them. Contact with family members is restricted: Only after two months can inmates and relatives converse via telephone through the prison glass. Once every three months, the women in UF 91/9 are allowed an overnight guest, male or female, for up to three nights. No one ever stays the full three, though -- at $5 a night, it's too expensive.

In the "short-visits room," the scene is like a colorful Russian bazaar -- women of all generations talking and crying. The outsiders bring food, clothes, cigarettes, and sanitary products -- all carefully inspected by the guards to prevent any contraband from sneaking through. A little boy lugs fruit for his inmate mother. An old gypsy woman breathlessly tells her daughter the latest town gossip. (Gypsies, an ethnic group in Russia, have their own laws, which often include women taking responsibility for men's crimes and actually doing the time for them.) Lutzkhak's mother brings her beads for her contest gown and painted Easter eggs--but the eggs, not on the list, are quickly confiscated.

THE TROUBLE WITH FREEDOM

Finally, contest day arrives. The prison is awash in hairspray, lipstick, nail polish, and all manner of female accoutrement not normally allowed in the prison. As the final decorations are pasted onto outfits, former inmate Natasha Patalakhova, 29, anxiously heads toward the other women, flowers in hand. Released seven months earlier, she has returned to see her friends compete. Patalakhova, who served eight years for armed assault, had been the acknowledged star of previous pageants, winning and even directing the event. But since leaving these prison walls, she has struggled to find her way. The government has refused to replace her lost passport because of her conviction, and without it, she cannot travel or apply for a job. (In Russia, a passport must be presented to any potential employer.) So, caught in this catch-22, Patalakhova is living in limbo.

Patalakhova's teen years in Siberia, as a refugee from Kazakhstan, taught her how to survive. Her hardened out outlook landed her in a dangerous gang, and when her boyfriend died of a drug overdose, Patalakhova single-handedly gathered a group of vigilantes to raid the dealer's den. Armed and masked, they infiltrated the home, but in a moment straight out of a Theodore Dreiser novel, Patalakhova heard a child cry out, "Mommy, who are these people?" and called off the crime. She was still arrested for armed assault, receiving a 14-year sentence. "My prison days continue to haunt me," she says. After serving eight years, Patalakhova finagled the coveted early release, no small thanks to her work in the pageants. She returned to her village of Voskresenka, where she is now apparently stuck. She has an option to work (illegally) as an aide at an elementary school, thanks to a family connection, but the job pays only $15 a month-- nowhere near enough to survive. Today, however, Patalakhova brings a different message, as she enters the prison like a rock star to hoots and cheers. Wearing thigh-high boots and wide, Jackie O. -- style sunglasses, she is the vision of free-market capitalism.

"Everything is great, girls!" she says. "I can't say that it's easy on the outside, but freedom is the best!" Her speech moves many to tears. Later, as the inmates return to their daily routine, the new infusion of energy is palpable. Nona Madjidova, the pageant favorite thanks to a giant lily concoction gown, has been crowned Miss Spring, but the real buzz is about Patalakhova's visit and the new Russia that awaits them all outside the prison walls. "I told them they could have a fresh beginning," says Patalakhova. "I told them to forgive each other, help each other, and strive to get home. What else could I say?"

-

Zendaya Changes From Off-Duty Basics to Springtime Glam

Zendaya Changes From Off-Duty Basics to Springtime GlamThe actress did a complete 180 in less than 24 hours.

By India Roby Published

-

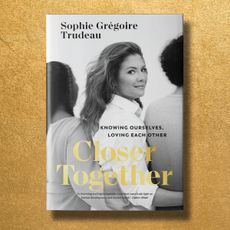

Sophie Grégoire Trudeau’s Next Chapter Is Still Being Written

Sophie Grégoire Trudeau’s Next Chapter Is Still Being WrittenHalf of a power couple for the last two decades, she’s learning through projects like her new book ‘Closer Together’ how to be more whole.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Prince Louis Turns 6—See the Adorable New Photo

Prince Louis Turns 6—See the Adorable New PhotoPrincess Kate was behind the lens.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Stylists on Why Leather Jackets Are a Great Investment

Stylists on Why Leather Jackets Are a Great InvestmentFashion insiders weigh in on their favorite styles.

By Lauren Tappan Published

-

Grown-Ups Are Rediscovering the Charm of Peter Pan Collars

Grown-Ups Are Rediscovering the Charm of Peter Pan CollarsFrom bibbed button-downs to round-neck leather jackets, this year's takes feel more sophisticated than sweet.

By Emma Childs Published

-

Sabrina Carpenter Wears Vintage Victoria's Secret Lingerie to Tease Upcoming Coachella Performance

Sabrina Carpenter Wears Vintage Victoria's Secret Lingerie to Tease Upcoming Coachella PerformanceHer look was pulled from the brand's 1997 archives.

By Lauren Tappan Published

-

The Best Chunky Sandals Prove Minimalism Is Out

The Best Chunky Sandals Prove Minimalism Is OutAnother footwear trend embracing maximalism in 2024.

By Lauren Tappan Published

-

The Brands to Shop for the Best Swimsuits

The Brands to Shop for the Best SwimsuitsFrom size-inclusive labels to sustainable and designer options, this list is all-encompassing.

By Lauren Tappan Published

-

The Best Vacation-Worthy Beach Dresses

The Best Vacation-Worthy Beach DressesFrom barely-there to playful fringe.

By Lauren Tappan Published

-

Could a 'Shirt Sandwich' Pull You Out of a Fashion Rut?

Could a 'Shirt Sandwich' Pull You Out of a Fashion Rut?The gourmet styling trick may help you fall back in love with your wardrobe.

By Emma Childs Published

-

The Best Spring Dresses Simplify Any Outfit Formula

The Best Spring Dresses Simplify Any Outfit FormulaStyle this wardrobe staple for any occasion, from farmer's markets to formal affairs.

By Lauren Tappan Published