My motivation for losing weight had always largely been vanity. The health warnings I'd read in magazines seemed like idle threats to an invincible teenager. But at 268 pounds at 20 years old, I was reminded of my mortality. I was obese and, worse, morbidly so, according to the height and weight charts I'd read online. It wasn't the peak I'd hit that stung. It was the numbers I imagined past the peak. Where do you go when you've only ever traveled northward on the scale?

Losing weight felt all at once easy and impossible. Even a person with the most basic health knowledge knows that to lose weight: You must move more. You must eat better. And you cannot binge eat.

Searching for body mass index (BMI) calculators and height-and-weight charts on my laptop, I found most information suggested that a healthy weight range for a 5'9" 20-year-old female was, on average, between 125 and 168 pounds. To meet the high end of the range, I'd have to lose 100 pounds. I had no idea what my body would look like at any of the lower, healthier weights, and it seemed arbitrary to be so specific, so far away. But I needed a goal to strive toward, so 140 it was.

The first three days—when I sobered to the fact that my life would be devoid of a deep fryer and two-for-one doughnuts—were almost unbearable. During the day, I'd feel fine eating healthily. I pulled sample diet menus from health-focused magazines; I didn't know the calories, the carbs, or the fat grams, only that the foods and portions in the meal plans were deemed healthy.

But when the sun went down each night, I felt that deep longing for sweets. I wanted cake.

But when the sun went down each night, I felt that deep longing for sweets. I wanted cake. I wanted chocolate. I couldn't watch television without wishing there could be a bowl of crunchy anything in my lap. I couldn't deem the day done without having that urgent stuffed fullness. I needed to be sufficiently sugared for sleep. Anxiety, sweaty palms, my body writhing in discomfort. An addict, I cried heartily and whole bodily, every night.

One week in, it got easier. By easier, I mean I agonized less. Perhaps my stomach shrank, or my mind's appetite did, whichever comes first. I took group fitness classes, used the cardio equipment, went jogging or walking—and tried to eat well. I lost just over 30 pounds in those three months of summer. I won't say it was fun, but I will say that, like anything new, and like any challenge you embark on, it was exciting at first to see the numbers on the scale fall.

Shortly after my junior year at the University of Massachusetts started, I joined Weight Watchers. Having always struggled with consistency in dieting, I began journaling what and how much I ate. This single act changed the way I viewed and valued eating, teaching me accountability and an awareness of my own hunger and fullness. There was a pleasurable quality in reporting to the journal, to myself, what I'd put into my body. It bred empowerment. It made me aware of small victories, all the times when I might have once eaten a half-dozen cookies or bowls of Cap'n Crunch and now was able to stop at one. These were milestones. Between that November and the following January, I lost around 20 pounds.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

What I learned in those six months had less to do with food and more to do with myself. It taught me about the nature of struggle and the feeling of strength that's born from it. But then, I started to slow. In progress, in patience. The vigilance, the exercise—they wore on me. The thrill of newness evaporated, and I began to feel bored with the whole process. What I thought next—just after I silently called myself a quitter, a loser, all manner of bad names—was simple enough: Oh, it's just going to suck for a while.

A heady dose of reality, it was a revelation. For once, I realized that weight loss wouldn't be like taking up jogging as a new hobby. I imagined it would be like running a marathon, where miles 10 through 26 just purely, uncompromisingly suck. Once I said this to myself, much of the journey seemed clearer. I recognized the distance, the real strength that I'd have to maintain.

Weight loss isn't like jogging—it's like a marathon where miles 10 through 26 just purely suck.

There is simply no denying the hard parts. The afternoons when I was midway between lunch and dinner and knew no amount of fruit would ever satisfy like a cupcake. The mornings when I found myself setting the pace on the treadmill and my legs felt leaden. Looking at my empty dinner plate after finishing a complete meal and wanting another full one to replace it. The times just before bed when I couldn't sleep because my mind was running the aisles of a supermarket grabbing Oreos and Lucky Charms in a fever.

I developed ways to distract myself, if only to narrowly escape a binge. I wrote in my journal. I called friends and talked about things other than food and weight. I went to the movies, where I had finally learned to be content without twice-buttered popcorn and Sno-Caps. I spent time in nature—the surest, quickest way to feel connected to something greater, and a way for me to realize that the world still spun on its axis whether or not I hated my body.

Moving to Italy for five months for a junior spring semester abroad was precarious. By the time I stepped onto Italian soil, my weight had dropped to 210 pounds. I continued to count points. My aim was to taste at least a bite or two of every last thing. I stuck to small, sensible portions, knowing that most of the food was rich. A handful of pillowy gnocchi, each no bigger than the tip of my thumb; six strands of tender homemade pappardelle in rich Bolognese sauce; grilled eggplant brushed with fruity olive oil; whole branzino with bones removed tableside.

I walked around Rome. Every monument, every antique church, every centuries-old piazza. I took the stairs when there were escalators; I walked to class when there were buses; I traveled to Naples and climbed Mount Vesuvius when my unbalanced self would have been better suited to sitting at its base. And there, in a city, a country, that doesn't necessarily believe in formal exercise, I learned to run. If I close my eyes tight, I can almost still feel the up-and-down jiggling of a body with essentially three filled backpacks of excess strapped to it.

Every day, every run, every walk was triumphant. The size-16 trouser jeans I'd bought just before coming to Italy required a tight belt to keep them on my hips. Even the belt needed new holes punched in it to make it smaller. Three months in, exercise was changing not only my shape, but my relationship with eating, too. I recognized that when I felt better physically, I was more motivated to eat well. The thought of potentially undoing any of the hard work I'd put into walking and running weakened the appeal of bingeing. For the first time in my life, I was able to eat decadently without gorging.

I left Rome in mid-May with a heavy heart. But I stepped off the plane a new girl. At the airport, I saw my reflection in the glass panel of windows. Whose body is this? was the only thought racing through my mind. Tall and slender and…normal. I knew it even before I stepped on the scale and saw that I had lost 55 pounds. I felt proud, alive. I was 21 now and, for the first time, appropriately weighed in for my height at 155 pounds.

There were days during the first weeks of being home when I just wanted to be out and about. I wanted to do all the things I hadn't done before with any measure of grace. I crossed my legs casually, coolly. I bought new clothing in sizes like 8 and, unbelievably, 6. I discovered how much cheaper it was to be thin—the way clearance racks practically shout your name, since they're loaded with smaller sizes. I found pacing the mall insanely fun, trying on clothes just because; it was exhilarating to pick any outfit and know that, at the very least, it would look OK. I began emerging from behind the curtains and walking barefoot to the trifold mirror at the center of the dressing rooms, an act I had detested before. I lost another 22 pounds over those next two months. And on the final day of summer, just as I was heading back to UMass for senior year, I saw a number I didn't think I'd ever see: 133.

On my first day back, the stares were unnerving. My eyes met those of others walking past. Each seemed more aware of me than before. I felt more accepted, respected. Not simply thin, but valued. Desirable. People I'd known since freshman year—who'd come to know me big—were stunned. Mouths hung gaping as they took in such a transformation. For the very first time, I was exactly the girl I'd always wanted to be. Those first few months when I inhabited a new, hard-earned body were a raw, explosive high. But after all highs comes a low.

A part of me was disdainful of the newfound attention: You see me now? I'm attractive now? Receiving the congratulations in some small way felt like accepting what I'd been before—all of my life—was wrong. Even though I'd often felt that way myself,

I resented that the size of my body was correlated to my worth as a person.

I resented that the size of my body was correlated to my worth as a person. The praise was a confirmation that thinness made me the better version of myself. And since something about it still felt foreign and unnatural to me, the outside praise made my insides cower. When I was fat, no one spoke aloud about my body. They couldn't. There's no decent way to bring up someone's obesity. And now the thinness was the centerpiece on the table of conversation.

With all the compliments I received for my weight loss, I feared returning to fat. What worried me almost as much as letting myself down if I gained it all back was letting everyone else down. The pressure, the foreignness of it all, caused the welling up of a deep, deep insecurity. I felt as though the tips of my fingers were moments from losing their death grip on the cliff I clung to. This wasn't the light and free, casual and content life I'd expected to start.

Instead, my thoughts were consumed by what I'd eat, when I'd eat, how I'd eat, and how much it all cost nutritionally. I became obsessed not only with counting calories and trying to stay at the exact same number each day, but with the healthfulness of the foods I consumed, too. All I wanted was to eat alone, in quiet, in secret. I needed to avoid eyes, speculation, and judgment of what I'd chosen to put on my plate. I imagined myself under a microscope, with everyone gathering closely to see what I'd do next. Paranoia set in and, with it, a greater need for compulsive control.

I began staying home more, not wanting, not even feeling able, to stray from routine. Being social was exhausting, as though it were taking an energy I didn't have in the first place. What I tried to display as a natural decline in my desire to go out partying was a cover for my fear of the calories that came with drinking and late-night eating. I couldn't save up enough calories in the day to waste on alcohol. I couldn't bear the thought of how hungry I might be after a night at the bars, when we'd return home and everyone would suggest takeout pizza and calzones. I would not, could not, commit to coffee dates, mall trips, movies, anything before I'd completed my workout for the day. I weighed and measured every morsel, never straying from my allowance of 1,600 calories a day. I panicked at restaurants when I was out of my own kitchenly control.

Eventually, I sought help—first, with a registered dietitian, who encouraged me to think less about food itself and more about the ways I was using it as something other than physical nourishment. When she told me my intense fears, preoccupations, and current obsessive thought patterns were in line with what's now known as OSFED, or Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder, I realized that all of my life was an eating disorder. No one who reaches morbid obesity is without a disorder of eating. Only now, I'd swung sharply from a lifetime of overeating to extreme restriction—both sides of the same obsessive coin.

She suggested I see a therapist, and there, I worked on what I'd come to know as my deepest, saddest realization: I'd used food, in one extreme or another, as love and comfort and joy for 20-some years. Amid the chaos of my childhood—an alcoholic father, a mother who worked two or three jobs and gave me food when she couldn't give me time or presence—and the insecurity of my adulthood, I could control food. When I felt nervous, food was reassuring. When I was anxious, food was soothing. When I was sad, food lifted me up. For every single emotion, I could turn to food.

The further I dug to uncover the roots of my relationship with food and overeating, the worse I began to feel. It was like taking every belonging I owned out of the cabinets and closets and drawers of my house and staring at the mess of it without ever being able to put it all away. There was no closure to the chaos. When I relayed this to my therapist, she suggested that I see a psychiatrist—someone who could evaluate me and potentially prescribe medication. The psychiatrist explained to me that it seemed to her that I'd always suffered from depression, and that it was likely something that ran in my family. Perhaps it was why Dad drank, she proposed. To soothe himself. To self-medicate. Perhaps it was why I ate. To soothe myself. To self-medicate. And I knew she was right.

Something I'd heard another formerly morbidly obese man describe in a documentary about obesity stuck with me: "Food addiction isn't like addiction to alcohol or drugs, where you can just remove it from your life. With food, you need it to live. You have to have it every day." The only way to get through food addiction is by making peace with food and uncovering the reasons we use it for anything other than hunger. I began to recognize the danger in attaching too much judgment to the foods I chose. Chocolate cake wasn't "bad," carrots weren't "good," and Bavarian cream doughnuts alone didn't make me morbidly obese. I was the one who abused food and gave it character. I was the one who combined them all in massive quantities, eating well beyond fullness. I learned to view food as a neutral entity, not positive or negative.

Slowly, I could go out to eat without an anxiety attack. Slowly, I could enjoy a social life like the one I once had. I had begun to feel limited by the "safe" foods I'd clung to since losing weight. To branch out, my nutritionist suggested I try having a nostalgic treat in place of my afternoon snack. She instructed me to pick one, plate it, sit at a table, and eat it as slowly as I could, so that all my senses were engaged. For my first treat, I chose a cupcake. I set it on a pretty antique plate, brewed a steaming cup of tea, and ate it at the kitchen table for the better part of 10 minutes. I'd made it special; I'd enjoyed it—and because of that, the eating lacked regret. And though I did wish I could have another, I didn't feel my old urge to binge. Day after day, I repeated my afternoon tea and cupcake, before moving on to chocolate bars, then doughnuts. The point of this daily dessert was proving to myself that I wasn't a monster around food. I would not eat with abandon anymore. I could have the foods that I loved and not abuse them, and I didn't have to live a life without them. I respected food, and in turn, I respected myself.

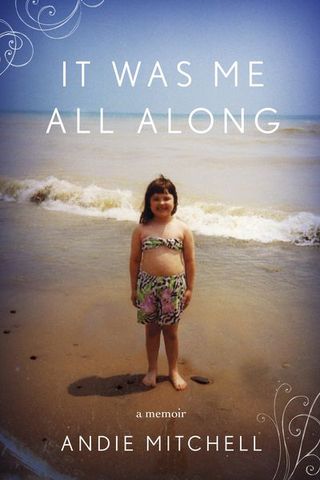

Adapted from It Was Me All Along: A Memoir, copyright © 2015 by Andie Mitchell, to be published by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of Random House LLC, on January 6. Available on Amazon.com.

This article appears in the January 2015 issue of Marie Claire.

-

Bitten Lips Took Center Stage at Dior Fall 2024 Show

Bitten Lips Took Center Stage at Dior Fall 2024 ShowModels at the Dior Fall 2024 show paired bitten lips with bare skin, a beauty trend that will take precedence this season.

By Deena Campbell Published

-

30 Spring Items That Solve My Expensive-Taste-on-a-Humble-Budget Dilemma

30 Spring Items That Solve My Expensive-Taste-on-a-Humble-Budget DilemmaSee every under-$300 spring item on my wish list.

By Natalie Gray Herder Published

-

Your Makeup Won't Budge With These Setting Sprays

Your Makeup Won't Budge With These Setting SpraysPrepare for 12-hour wear.

By Sophia Vilensky Published

-

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"Senator and breast cancer survivor Amy Klobuchar is encouraging women not to put off preventative care any longer.

By Senator Amy Klobuchar Published

-

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My Body

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My BodyI'm plus size, but after I decided to pose nude for photos, I suddenly felt more body positive.

By Kelly Burch Published

-

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?Much like abortion, surrogacy, and IVF, becoming an egg donor was a reproductive choice that felt unfit for society’s standards of womanhood.

By Lauryn Chamberlain Published

-

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in Check

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in CheckGut health = wealth.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo Olympics

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo OlympicsShe withdrew from the event due to a medical issue, according to USA Gymnastics.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Truth About Thigh Gaps

The Truth About Thigh GapsWe're going to need you to stop right there.

By Kenny Thapoung Published

-

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” Condition

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” ConditionDespite having no outward signs, they can be brutal on the body and the mind. Here’s how each woman deals with having illnesses others often don’t understand.

By Emily Shiffer Published

-

The High Price of Living With Chronic Pain

The High Price of Living With Chronic PainThree women open up about how their conditions impact their bodies—and their wallets.

By Alice Oglethorpe Published