Shortly before their first visit to Guantánamo Bay, on the day after Christmas in 2004, Kristine Huskey and her colleagues were told they could put together a special care package for their 12 Kuwaiti clients, none of whom they'd ever met. Stunned by this small act of grace — you can bring food down there? — the lawyers were suddenly faced with a rather peculiar challenge: What would a dozen observant Muslims want to eat after two years in American custody? They settled on traditional Middle Eastern fare: Nuts. Dates. A baklava they'd bought from a famous store in Detroit. "We put together this whole spread," says Huskey. "And they thanked us — they were very polite about it. But it turns out what they really wanted was pizza and Twix."

Over the next two years, Huskey learned the cravings of her clients by heart. For Fawzi al Odah, she almost always brought McDonald's french fries and ice cream. For Abdullah Kamal al Kandari (her favorite, a former member of the Kuwaiti volleyball team), she brought a 12-inch cheese pie from Pizza Hut. Each time she visited, at least two guards inspected her boxes and bags and confiscated all utensils, which, Huskey notes, made eating the ice cream a problem — although under the circumstances, this was the least of her clients' complaints.

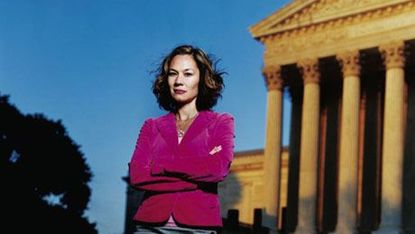

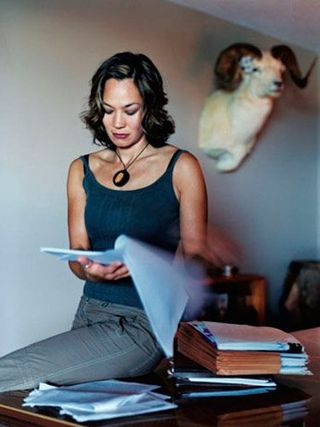

Compared with other Arab countries, Kuwait is fairly receptive to Western ideas and influence, which may help explain why Huskey's clients chose fast food over baklava. Whether they'd choose to accept Huskey as their lawyer, however, was another matter entirely. Though Kuwait's attitudes toward women are more progressive than most of its neighbors in the region (the country's workforce is 35 percent female, and its female literacy rate is roughly 83 percent), its women were only extended the right to vote last year, and Huskey, by virtually any measure, is a deeply unconventional gal. Though tiny and lithe, she's blunt and outspoken, and she likes to pair her chic suits with calf-hugging, high-heeled boots. ("They've sort of become my statement," she says.) While most Kuwaiti women over 30 are married with three children, Huskey, at 39, is still single, still without kids, and knows how to fire a gun. (She keeps the head of a ram, which she shot herself, mounted on her living room wall.) Her boyfriend of several years is a staunch Republican. "Which makes for some pretty heated debates," she says.

Perhaps most unusually, Huskey worked part-time as a model before she went to the University of Texas for her law degree, a mini career that once earned her a starring role as a dancer in the 1993 video "Knockin' Da Boots" by H-Town. In it, she wore nothing but a purple satin bra and panties. "At least it was MTV before the thongs," she says.

Needless to say, when Huskey first went down to Guantánamo Bay, she was fully clad in a business suit and sensible shoes. Yet she still wondered if she was covered enough. "I brought a head scarf with me, which I was ready to put on," she says. "I was willing to set my feminism aside and let my male colleagues do the face-to-face work while I sat in the corner and took notes, and then go to work on their case back in Washington." But it never came to that. From the day they first met, Huskey's clients accepted her as their lawyer.

How does this happen, exactly? How did a former MTV dancer with a passion for outré footwear and hunting become one of the key human-rights lawyers for Guantánamo detainees? Huskey would doubtless say that it was the logical next step in a rather eccentric life, one that has always involved a fair measure of creativity, independence of spirit, and multicultural fluency. Because her mother is Filipino and her father is "a big white guy whose every other word is a swear," she was forced, from day one, to navigate between two worlds. Because her father was a pilot for various oil companies, she lived in Alaska until age 12, and then Saudi Arabia, where she grew accustomed to the rhythms and norms of life in a Muslim society. At 18, she followed her boyfriend, an aid worker for UNICEF, to Angola during that country's civil war. "And that relates to Guantánamo Bay," she points out. "When people ask what my Kuwaiti clients happened to be doing in Afghanistan in the middle of a war, I remind them that people do go and offer humanitarian assistance in dangerous places. It's not unheard of." Two years later, Huskey moved to New York City and put herself through Columbia University by tending bar. She graduated Phi Beta Kappa.

Huskey first started working on the Guantánamo case in March of 2002, after Thomas B. Wilner, her mentor at the law firm of Shearman & Sterling and a lawyer in Washington for 35 years, was contacted by the families of the detainees. Wilner chose Huskey as a member of the legal team in part for her fearlessness: "He said I was one of the only associates — even when I was junior level — who wasn't deferential to the partners," she says, nibbling on a Triscuit, giving her shiny dark hair a sly shake. She's sitting in her new office at the International Human rights Law Clinic at American University Washington College of Law in DC, where she has just accepted a teaching job. "And he liked that I wasn't going to kowtow. That I spoke my mind." Wilner also suspected that Huskey's unabashed femininity would be an asset. "The first thing anybody notices about Kristine is that she's extraordinarily attractive," he says. "Too many women try to become good lawyers by being incredibly hardass. Kristine is totally at ease using her feminine side to get her point across — and she's all the stronger in making her case because of it."

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

By April of 2002, Wilner and Huskey were on a plane to Kuwait. By May, they'd filed a complaint with the DC District Court that their clients were being robbed of due process. The court threw out the case. The lawyers appealed; their appeal was denied. Finally, they took their case to the Supreme Court and won in June of 2004, allowing for the first time the legal representation of Guantánamo detainees. Six months later, they were on their way to Cuba.

"It was all very professional," says Huskey, describing the initial visit. "It was basically, 'I'm your lawyer; I've met your families; I've been to Kuwait. Describe to me what your life is like in here...'" She found herself compiling a staggering list of grievances. As military officials themselves admit, 41 inmates have attempted suicide since 2002 (three actually succeeded in July), and human-rights groups have catalogued a range of horrors and humiliations. In September 2005, more than 125 detainees staged a hunger strike to protest their conditions — one of Huskey's clients dropped down to 93 pounds. Health officials had to strap him to a chair, loop a feeding tube through his nose, and pump him full of Ensure.

When Huskey returned to Washington, one of the first things she did was file a motion with the DC District Court to improve her clients' living conditions. "I asked for adequate medical and dental care — they'd never received any dental treatment," she says. "And I asked that they be allowed to exercise more. They were only getting out of their cells one or two times a week for 20 minutes." At a press conference, she and Wilner mentioned that some of the detainees complained their Korans were being defaced. Four months later, Newsweek ran a stronger version of this charge, saying a Koran had been flushed down the toilet. (The magazine later printed a retraction saying it couldn't quite substantiate the claim.)

But more valuable than tallying grievances, says Huskey, and even more valuable than giving legal counsel, was the simple human contact she provided clients. "You have to understand," she says, "we spent so much time talking about how grim the conditions were. It got to the point where they didn't even want to talk legal strategy with me, because they didn't think the law was working."

As conversation shifted to the personal, Huskey found herself relying on her native charms. And the men began confiding in her. One can see how they would: Though hardened and worldly, there's also something innocent and childlike about Huskey — she reminds one almost instantly of Holly Golightly, on her weekly trips to visit mobster Sally Tomato in Sing Sing. She smiles easily and listens well; she speaks in a melodic sing-song. ("I see no reason why smart women can't be attractive and girly, and attractive women can't be smart," she says. "Really, you can be both.") One of the detainees soon began showing her pictures of his daughters back home and discussing the problems he was having with his teenage girl. Another broke into a smile — for the first time — when Huskey screamed as a cockroach climbed onto her shoe. With the volleyball player, she talked about her modeling. "That, and the fact that I do triathlons to de-stress," she says. "It was sort of weird. Almost like a blind date."

The comparison might sound strange, trivializing — an analogy a former model, not a human-rights lawyer, would be apt to make. But Huskey clarifies: "These men are bored senseless." She points out that Guantánamo Bay isn't like a federal prison, or even a maximum-security prison, where inmates are allowed contact with their families. Here, they are suspended from all connection to the outside world. "They don't have anyone to talk to except interrogators and guards," she says. "I became their sister, their mental-health person, everything. And that's what those discussions — about modeling and volleyball — were about. Tiny moments of normalcy."

Guantánamo Bay is America's oldest overseas naval base, a 45-square-mile swath of land at the southeast end of Cuba, a country with which America has no diplomatic relations. Until June of 2004, the only Americans to visit the detainee prison camp were members of Congress, officials from the International Red Cross, and a few reporters. Then the Supreme Court heard the arguments in Huskey's case, Rasul v. Bush, and ruled that Guantánamo prisoners were entitled to claims of habeas corpus. Soon, a modest group of lawyers, Huskey among them, began filing down to Cuba. Today, these lawyers know this bleak, other-planetary place better than almost anyone on earth.

Usually, Huskey and her colleagues arrive at night, after a three-and-a-half-hour charter flight on a turbo-prop jet. They stay on the leeward side of the base, where there's nothing but a bare-bones dormitory ("the bachelor quarters"),

a mess hall (already closed), and a bar (where Huskey orders a vodka tonic, while her male colleagues opt for beers). The next day, she's shuttled by military escorts to the more populated windward side, where there's a Pizza Hut, a McDonald's, a Navy Exchange store, and a souvenir shop (Huskey confesses she has purchased a couple of Guantánamo Bay T-shirts).

Then they're taken to the actual prison complex, a 15-minute ride by military bus down a solitary road dotted with giant iguanas and banana rats. When she arrives, each man is waiting in a windowless cell. One by one, they're are brought from behind bars to meet in an adjoining area, where they spend the entire time shackled to an iron ring in the floor.

The allegations against the 12 Kuwaiti detainees vary widely. Some, she admits, are "very worrisome." One client is accused of supporting the Taliban during the American invasion. But she's less persuaded by others. Abdullah Kamal al Kandari is being held on evidence that he wore the type of Casio watch preferred by al Qaeda terrorists to detonate bombs; that his supposed alias was found in an al Qaeda member's computer recovered in Afghanistan; and that he was traveling near the Afghan border during the invasion with $10,000 cash. (He, in turn, says that many Muslim men have such watches, that he doesn't have an alias, and that he was donating the money to a charity he found through his local mosque.)

"I've looked at Abdullah's file over and over again," Huskey says. "And I've talked to him a million times. Even if you believe the allegations against him, that still doesn't make him a terrorist."

True, but carrying $10,000 in cash to the Afghan border would arouse almost anyone's suspicions... "I'm not naive," she says sharply. "Of course I've considered the possibility that the $10,000 was to support al Qaeda. In fact, sometimes I have this nightmare/fantasy that my clients will get released, go back to Kuwait, and join al Qaeda."

So at moments like this, what does she tell herself?

"That this is why we have fair hearings. We could guess. We could speculate. But we could also determine, through a fair process, if the allegations against my clients are true. Everyone deserves a process based on good evidence, not torture or hearsay."

This July, Huskey decided to join the International Human Rights Law Clinic full-time, to devote herself to cases like Rasul. Paradoxically, this means saying good-bye to her Kuwaiti clients, who will continue to be represented by Shearman & Sterling. Today, Huskey has a more controversial client, Omar Khadr, a Canadian born to Middle Eastern parents, who, unlike the Kuwaitis, is charged with a war crime: American authorities say he lobbed a grenade at a U.S. soldier in Afghanistan and killed him. Huskey has no idea when his trial will take place — considering that President Bush just transferred 14 high-level terrorist suspects, including top lieutenants to Osama bin Laden, to Guantánamo whose cases presumably take precedence over Khadr's.

"I realize there's a difference between Omar and my previous clients," she says. But she still finds a way to relate to him, to humanize him. "He was picked up when he was 15. So no matter what the allegations are against him, he should have been given special status as a child. And he wasn't."

At the end of September, the Senate and House passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006, outlining future protocols for the treatment of detainees. It can barely be considered progress. Prisoners at Guantánamo now have the right to see some, but not all, classified evidence being used against them in military tribunals. And they no longer have the right to challenge their detainee status in a U.S. court of law.

Huskey hopes there'll be yet another Supreme Court challenge to the act. Like most human-rights lawyers, she believes that preserving the integrity of the legal system is the cardinal value, and also the ultimate one. She doesn't live in a universe of moral absolutes.

"Some people may be horrible, through and through," she concedes. But then she adds, with her idiosyncratic humanism, "On the other hand, that's the essence of what being a human-rights lawyer is: You believe that by being human — just by being human — you're entitled to certain rights. They may be scant, but you're entitled to them."

-

Melissa McCarthy Defends Meghan Markle From Critics Who Are "Threatened" by Her

Melissa McCarthy Defends Meghan Markle From Critics Who Are "Threatened" by HerMcCarthy once starred in the duchess' 40th birthday video.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Zendaya Says She Might Just "Go Away for a While" During 'Euphoria' Hiatus

Zendaya Says She Might Just "Go Away for a While" During 'Euphoria' HiatusRest is best!

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Celebrate Earth Month With Our Feel-Good Fashion Report

Celebrate Earth Month With Our Feel-Good Fashion ReportYour guide to being more sustainable in 2024.

By Anneliese Henderson Published

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenIt's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

EMILY's List President Laphonza Butler Has Big Plans for the Organization

EMILY's List President Laphonza Butler Has Big Plans for the OrganizationUnder Butler's leadership, the largest resource for women in politics aims to expand Black political power and become more accessible for candidates across the nation.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

Want to Fight for Abortion Rights in Texas? Raise Your Voice to State Legislators

Want to Fight for Abortion Rights in Texas? Raise Your Voice to State LegislatorsEmily Cain, executive director of EMILY's List and and former Minority Leader in Maine, says that to stop the assault on reproductive rights, we need to start demanding more from our state legislatures.

By Emily Cain Published

-

Your Abortion Questions, Answered

Your Abortion Questions, AnsweredHere, MC debunks common abortion myths you may be increasingly hearing since Texas' near-total abortion ban went into effect.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Future of Afghan Women and Girls Depends on What We Do Next

The Future of Afghan Women and Girls Depends on What We Do NextBetween the U.S. occupation and the Taliban, supporting resettlement for Afghan women and vulnerable individuals is long overdue.

By Rona Akbari Published

-

How to Help Afghanistan Refugees and Those Who Need Aid

How to Help Afghanistan Refugees and Those Who Need AidWith the situation rapidly evolving, organizations are desperate for help.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

It’s Time to Give Domestic Workers the Protections They Deserve

It’s Time to Give Domestic Workers the Protections They DeserveThe National Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, reintroduced today, would establish a new set of standards for the people who work in our homes and take a vital step towards racial and gender equity.

By Ai-jen Poo Published

-

The Biden Administration Announced It Will Remove the Hyde Amendment

The Biden Administration Announced It Will Remove the Hyde AmendmentThe pledge was just one of many gender equity commitments made by the administration, including the creation of the first U.S. National Action Plan on Gender-Based Violence.

By Megan DiTrolio Published