Ri Asada, 22, sips iced tea in a Tokyo café, oblivious to a man at the next table who is ogling her bare thighs. She's dressed in a perennially popular Japanese style: high heels, over-the-knee socks, and a lacy minidress, with doll-like makeup and colored contact lenses. It is a provocative look, yet Asada, an economics graduate who still lives with her parents, insists it's "just fashion." She is not interested in attracting the opposite sex. She is not interested in sex, period.

"The thought of sleeping with someone never crosses my mind," she says. "I don't even like holding hands."

Apparently, Asada's lackluster libido is not unusual here. Recent Japanese studies point to a startling trend among the nation's under-40s: a rising aversion to sex and dating. In Japan, where there's a name for every new social twist, the media have dubbed it "Celibacy syndrome," "No-sex sickness," and, ominously, the "death of sex." When combined with the shrinking birthrate and aging population, the decline is so serious that the nation "might eventually perish into extinction," claims Kunio Kitamura, the head of the Japan Family Planning Association (JFPA).

Additional research does little to curb such alarmism. A JFPA survey released in January 2013 found that 45 percent of women ages 16 to 24 "were not interested in or disliked sexual contact." More than 25 percent of men in the same age group— supposedly in their turbocharged hormonal prime—felt the same way. Things don't improve with age: A 2011 government survey reported that 49 percent of Japanese women ages 18 to 34 don't have a boyfriend or husband, while 61 percent of heterosexual men are also single. (There are no available figures for same-sex relationships.)

Further, more than 40 percent of Japanese marriages are classed as "sexless," meaning couples of child-bearing age who rarely or never have sex. Japan also ranked lowest in condom-maker Durex's sexual Wellbeing Global Sex Survey of 26 countries: A question on sexual frequency found that, while around 53 percent of adult Americans and 82 percent of Brazilians had sex at least once a week, only 34 percent of Japanese did.

What is going on? The core of it, it seems, is that men's and women's lives are moving in opposite directions. In the past two decades, Japanese women have become more independent and career-focused. At the same time, the economy has stagnated, and the traditional "salaryman" corporate culture has waned. No longer in the guaranteed role of breadwinner, many men have become less ambitious at work and more passive in love, experts say. "Men and women have fewer shared goals, so it's become harder for them to connect romantically and sexually," says Kitamura. "Also, their expectations of each other have not adjusted. Many men still want women to be submissive, while women are turned off by unambitious men. To put it bluntly, many people feel that relationships between men and women are just a pain in the neck."

Tokyo-born Asada swore off sex and dating three years ago, after a one-year relationship in college with a fellow student. "When we broke up, I realized I'd spent the whole time thinking about only his needs. That's what he expected," she says. "I'm much happier now that I'm single."

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Asada works as a student adviser at a "cram school" that provides private academic tutoring for college applicants. Tall and attractive, she often gets asked out on dates by colleagues. She always refuses. "My weekends are too precious." Her favorite pastimes are shopping for clothes and makeup and playing games on her smartphone. Asada says she doesn't miss sex, and casual hookups are not for her. "In theory you should be able to have sex just for fun, but in reality it's too much trouble." In fact, casual sex is problematic for most young women in Japan. While the country is known for its liberal attitudes toward erotic pleasure, double standards apply to women. "Girls can't have casual flings without being judged," says Asada.

Interestingly, such double standards have intensified in recent years as mass-market pop culture has exploded. The fantasy ideal for women under 25 reflected in anime cartoon characters and all-girl "idol" bands is impossibly cute and virginal: Women are not supposed to show any signs of sexual experience or desire. Not everyone buys into this chaste ideal, but its influence is profound. In February, singer Minami Minegishi, 20, a member of the hugely popular all-girl pop

group AKB48, received more than 3 million hits on YouTube when she posted a video of herself apologizing in tears to her fans. Shockingly, she had shaved off all her hair as an act of penance. Her crime? She had been caught on camera sneaking home after spending the night with her boyfriend.

It's not just young women who are turned off by the confusing world of modern romance. In bustling Harajuku, Tokyo's street-fashion hub, Kensuke Todo, 20, says dating and sex are too complicated. "Either girls are not interested in you at all, or they want a serious relationship," he says. The college student, who is majoring in social affairs, says he enjoys his hobbies of photography and fashion much more than chasing girls for sex. "I'd rather spend my money on clothes than buying women dinner or gifts," adds Todo, who's wearing pricey Paul Smith pants and a Comme des Garçons shirt.

Todo is too shy to talk about whether he still has sexual urges, or what he does to satisfy them without dating. But he admits that quite a few of his male friends who are also celibate turn to virtual girlfriends and sexually explicit comics for excitement. "It's quite common," he says, blushing. Vast amounts of pornography are readily available in Japan. Many media commentators are debating whether the prevalence of such imagery—which demeans women and sets up unrealistic fantasy expectations for men—is another factor alienating the sexes from each other in real life.

Tomomi Yamaguchi, assistant professor of anthropology at Montana State University, agrees this could be part of the malaise but says Japan's outdated attitudes toward women overall are one of the main underlying reasons. "The country needs to stop treating women like either sex objects or baby-making machines and allow them to be themselves." Better sex education, more measures to help women combine a career and family, and less pressure on men to be the sole providers would also help spark the nation's collective love life, the cultural expert believes.

If such steps are not taken, young women like Asada could remain single all their lives. According to projections by the government's National Institute of Population and Social Security, women in their early 20s today have a 1 in 4 chance of never marrying. Their chances of remaining childless are even higher: almost 40 percent. Japan's birthrate has been falling steadily for years, and fewer babies were born in 2012 than in any other year on record. (The year before that—as the proportion of elderly people skyrocketed — adult diapers outsold baby diapers in Japan for the first time.) The nation is on the brink of ahuge demographic crisis: At current levels, the population of 127 million is projected to fall by a whopping one-third by 2060.

In many ways, the country has only itself to blame. For years, educated women in Japan have been postponing marriage and children because it's so difficult for them to combine work and family. Eri Tomita, 31, loves her job in the human resources department at the central Tokyo office of a French bank. A college graduate and fluent French speaker, she fought hard in Japan's overcrowded job market to establish her career and has no intention of giving it up. "My job is part of my identity now. I like having responsibilities at work and being financially independent."

In the male-dominated corporate world, workplace discrimination is blatant as soon as a woman marries. "The chances of promotion stop dead because the bosses assume you will get pregnant and leave. I've seen it many times," says Tomita. Once a woman does have a baby, she adds, it's simply impossible to keep working. "You have to work long, inflexible hours, so you have to quit. You end up being a housewife with no income of your own. This is not an option for modern women like me."

Slim and beautiful with long hair and a stylish fashion sense, Tomita has made a conscious decision not to get romantically involved at all so she can focus on her work. She lives alone and socializes with her girlfriends. "I have many single friends who are all career girls like me. We like to go out to French or Italian restaurants and have expensive food and wine."

The phenomenon of groups of single, financially solvent women meeting up socially has become so common in Japan that it has a name: joshi-kai, or "ladies parties." Restaurants and resorts offer joshi-kai special menus and discount travel packages to attract the lucrative all-female customers. On Valentine's Day this year, one restaurant even offered a special joshi-kai deal so women could still celebrate the occasion without men. The girls' get-togethers are similar to those in HBO's Sex and the City—the show was a huge hit when it aired in Japan—except for one crucial difference: "We never talk about sex," says Tomita. "We talk about our jobs, about shopping and makeup, about movies. Sex is not a priority." Tomita explains that, as for younger women like Asada, casual sex is loaded with too many negatives. "I often get asked out by older married men who want an affair. They assume I must be desperate because I'm still single," she sighs. "Men my own age are intimidated." Tomita says she would like to marry around the age of 40 if she can meet a man who supports her desire to work. But, worryingly, the decliningbirthrate has caused a backlash against career women. In a 2012 government survey, 51 percent of the population said they believed women should stay at home while men go out to work — up 10 percent from a similar survey in 2009.

Japan, it seems, just can't get it right. Men, too, feel burdened by such old-fashioned attitudes about gender roles. Amid the ongoing economic recession, many men feel that the pressure on them to be the main family provider is unrealistic. At the same time, the glaringly obvious answer— settling down with career women like Tomita and sharing the burden—is not feasible because the corporate world is too rigid to allow both parents to work. This apparently insoluble situation has created a new breed of romantically apathetic single men. naturally, they have a name: soushoku danshi, or "herbivore men" (literally "grass eater" in Japanese).

Satoru Kishino, 31, is a self-confessed herbivore man who says he doesn't mind the label because it has become so commonplace. He defines it as a "straight man for whom sex and relationships are not a priority." "I'm not interested in having a girlfriend or getting married," says Kishino, who works at a fashion accessories company as a designer and quality control manager. "I enjoy my life the way it is —going to work, relaxing with friends and family."

Like Asada and Tomita, Kishino says he never lacks entertainment. "I like cooking and cycling and going to see Japanese comedy theater." Well groomed with gelled spiky hair and a friendly face, Kishino says he has many female friends. "I do find some of them attractive, but dating is too troublesome. I don't want to have the responsibility of being someone's boyfriend, or have to worry that they hope it will lead to marriage."

Moreover, Kishino says, dating has become so overcommercialized in Japan, with constant pressure to spend money on expensive gifts, dinners, and "romantic getaways," that he can't afford it. He has learned to live without sex. "I don't dislike sex, but you have to jump through hoops just to get a girl into bed. I can't be bothered, and I'm fine being alone."

Still, not everyone in Japan has given up on sex and romance. On a sunny afternoon in the upscale Tokyo district of Aoyama, around 300 singletons are attending a private matchmaking event in the basement of a restaurant. Matchmaking has a long history in Japan — until around 1970 many marriages were still arranged through intermediaries. Today, both the government and private companies are trying to reverse the apparent incompatibility of the sexes by playing cupid with organized get-togethers.

Masumi Sasaki, 34, a pharmacist, has come along with a female friend "to see what it's like." The basement is dark and packed with bodies brandishing smartphones. They are playing a speed-dating game that involves getting as many phone numbers from the opposite sex as possible. Sasaki quickly decides the event is not for her. "I just came here to talk to people in a normal fashion," she says.

Retreating to a coffee shop, Sasaki explains that she is used to being single and celibate and is not desperate to find a partner. "I panicked around the age of 30 and tried hard to find someone to marry. But when it didn't happen, I stopped thinking about it." In fact, it doesn't take long for Sasaki to reveal that the true love of her life at the moment is not a person but her 8-year-old female pet rabbit, Nichi. Sasaki lives alone in a small apartment just outside Tokyo with ginger-hued Nichi and spends much of her free time with her. "On weekends I often take Nichi to special 'rabbit cafés' where she can play with other rabbits," says Sasaki.

While it might sound like one of those "only in Japan" tales that the West loves so much, the rise in pet ownership is a genuine phenomenon. Amid the tough economic and romantic climate, more people have been buying pets such as dogs, cats, and rabbits and pampering them like surrogate children or partners. The estimated number of pets across the nation is now more than 22 million, and the industry is worth around $12 billion a year. Indeed, Sasaki confesses she loves rabbits so much it's hard for men to compete. "I met a man at a rabbit convention and afterward he friended me on Facebook," she says. "At first I didn't know who he was. It was only when he posted a photo of his rabbit that I remembered him."

So is it really end-times for sexual relationships in Japan? Interestingly, a 28-year-old man at the same matchmaking event as Sasaki agrees with those who believe that the country's anachronistic attitudes toward women are the root of the problem. "I find women who are independent and have their own careers much more sexually attractive," says Shinsuke Yasuda, an IT systems engineer. "I don't want someone who is subservient." Many young Japanese men feel the same way, but "society has to catch up" to make equal relationships possible, Yasuda says. "At least some of us are trying," he adds, before disappearing into the darkness to collect more phone numbers. Maybe there's hope yet.

-

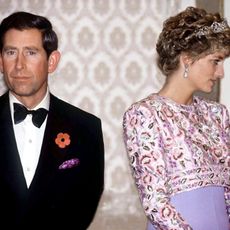

Princess Diana Revealed to a Royal Author the Real Reason Why Her Marriage to Prince Charles Ended Not Long Before She Died in 1997

Princess Diana Revealed to a Royal Author the Real Reason Why Her Marriage to Prince Charles Ended Not Long Before She Died in 1997And no, it apparently wasn’t Camilla Parker-Bowles.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Princess Martha Louise of Norway Sets Wedding Date with Fiancé Shaman Durek Verrett After a Two Year Engagement

Princess Martha Louise of Norway Sets Wedding Date with Fiancé Shaman Durek Verrett After a Two Year EngagementAlready billed as “one of the most beautiful high society weddings of the year,” the celebration will last for four days.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Heidi Gardner Opens Up About Viral Moment She Broke Character During ‘Saturday Night Live’ Beavis and Butt-Head Sketch

Heidi Gardner Opens Up About Viral Moment She Broke Character During ‘Saturday Night Live’ Beavis and Butt-Head Sketch“I just couldn’t prepare for what I saw.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

The Best Birth Control Pills for Your Body Type

The Best Birth Control Pills for Your Body TypeNo bloat, no meltdowns, no breakouts, no baby.

By Karen Springen Published

-

Good News for Your Binge-Watching Habit: Apparently It Makes You Closer as a Couple

Good News for Your Binge-Watching Habit: Apparently It Makes You Closer as a CoupleAwwwww.

By Megan Friedman Published

-

My First Year of Marriage Almost Ended in Divorce

My First Year of Marriage Almost Ended in Divorce"It's not always sexy, and it's not easy."

By Natasha Huang Smith Published

-

12 Things Only People Dating in Big Cities Know

12 Things Only People Dating in Big Cities KnowWelcome to the worst dating scene on earth.

By Lori Keong Published

-

Sex! Now! Please!

Sex! Now! Please!My boyfriend, who lives 1300 miles away, arrived last night.

By Marie Claire Published

-

I Wasted Two Years "Dating" a Man I Never Met

I Wasted Two Years "Dating" a Man I Never MetWe talked on the phone for hours a day, professed our love, and had intimate phone sex — but never a single date.

By Laurie Sandell Published

-

I Was Seduced—and Abused—by a Porn Star

I Was Seduced—and Abused—by a Porn StarDawn Schiller recounts her dark, scary affair with legendary adult film star John Holmes.

By Abigail Pesta Published

-

My Lost Love

My Lost LoveHe was my childhood sweetheart, my relationship safety net — until he wasn't.

By Sarah Wexler Published