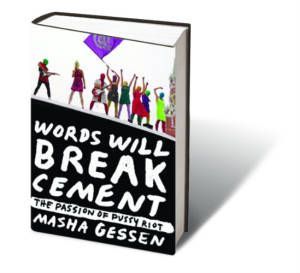

ON FEBRUARY 21, 2012, five women in brightly colored dresses, tights, and balaclava masks walked into a cathedral in Moscow to stage a "punk prayer," calling on the Virgin Mary to free Russia from Vladimir Putin. The world now knows those masked women as Pussy Riot, the Russian feminist punk rock group. (Three of the women were later arrested, put on trial, and sentenced to prison for "hooliganism.") Masha Gessen, a journalist who lived in Moscow for 20 years, had unprecedented access to the women—they even wrote her letters from jail—and charts their journey from budding punk activists to freedom fighters in her new book, Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot (Riverhead).

MARIE CLAIRE: You've said the arrest of some members of Pussy Riot was pivotal. Why is that?

MASHA GESSEN: The arrest was completely outside the scope and scale of the reactions we'd encountered in Russia. With few exceptions, we had not seen people going to prison for peaceful protests. Now there are about 70 political prisoners in Russia—a majority of them arrested after Pussy Riot.

MC: Let's talk about Nadya Tolokonnikova, 24, whom you portray as the soul of the group. How was her time in the penal colony?

MG: She was made to work extremely long hours and was incredibly sleep-deprived and underfed. She eventually went to the warden and demanded he bring prison conditions in line with the law. He threatened to have her killed. That's when she decided to go public and to go on hunger strike. She became very, very ill. She was hospitalized. And then she disappeared for 26 days. At this point, the great news is she's alive.

MC: What do you make of Putin's amnesty, which grants freedom to women who have small children, as the Pussy Riot members do?

MG: It's transparently cynical: They may get a month or two shaved off their sentences [they were set to be released in March] just so they can be out before the Olympics. On the other hand, even one less day in a Russian prison is good news.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

MC: Let's talk about you, too. Why did you leave Russia in December? I understand as a lesbian and as a parent, you no longer felt like you could live there.

MG: In the past year, there has been a large number of very restrictive, very scary laws that have created not just a chilling effect but an atmosphere of absolute hopelessness for many Russians. One of the proposed laws would take custody away from any parent "who allows for nontraditional sexual relations." That's personal. It will affect a lot of people, but the sponsors of the bill have made it clear this one is for me. That's when you have to admit defeat. If you're going to go after my kids, I have to leave. You win.

Kayla Webley Adler is the Deputy Editor of ELLE magazine. She edits cover stories, profiles, and narrative features on politics, culture, crime, and social trends. Previously, she worked as the Features Director at Marie Claire magazine and as a Staff Writer at TIME magazine.

-

Katy Perry's Top Almost Came All the Way Off on 'American Idol'

Katy Perry's Top Almost Came All the Way Off on 'American Idol'LOL.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

David Beckham Shares Heartwarming Tribute to Victoria Beckham on Her 50th Birthday

David Beckham Shares Heartwarming Tribute to Victoria Beckham on Her 50th BirthdayCRYING.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Zendaya's Method Dressing Marathon Is Over

Zendaya's Method Dressing Marathon Is OverShe found a new way to serve in custom Vera Wang.

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenIt's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

EMILY's List President Laphonza Butler Has Big Plans for the Organization

EMILY's List President Laphonza Butler Has Big Plans for the OrganizationUnder Butler's leadership, the largest resource for women in politics aims to expand Black political power and become more accessible for candidates across the nation.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

Want to Fight for Abortion Rights in Texas? Raise Your Voice to State Legislators

Want to Fight for Abortion Rights in Texas? Raise Your Voice to State LegislatorsEmily Cain, executive director of EMILY's List and and former Minority Leader in Maine, says that to stop the assault on reproductive rights, we need to start demanding more from our state legislatures.

By Emily Cain Published

-

Your Abortion Questions, Answered

Your Abortion Questions, AnsweredHere, MC debunks common abortion myths you may be increasingly hearing since Texas' near-total abortion ban went into effect.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Future of Afghan Women and Girls Depends on What We Do Next

The Future of Afghan Women and Girls Depends on What We Do NextBetween the U.S. occupation and the Taliban, supporting resettlement for Afghan women and vulnerable individuals is long overdue.

By Rona Akbari Published

-

How to Help Afghanistan Refugees and Those Who Need Aid

How to Help Afghanistan Refugees and Those Who Need AidWith the situation rapidly evolving, organizations are desperate for help.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

It’s Time to Give Domestic Workers the Protections They Deserve

It’s Time to Give Domestic Workers the Protections They DeserveThe National Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, reintroduced today, would establish a new set of standards for the people who work in our homes and take a vital step towards racial and gender equity.

By Ai-jen Poo Published

-

The Biden Administration Announced It Will Remove the Hyde Amendment

The Biden Administration Announced It Will Remove the Hyde AmendmentThe pledge was just one of many gender equity commitments made by the administration, including the creation of the first U.S. National Action Plan on Gender-Based Violence.

By Megan DiTrolio Published