As I drive into the Texas Correctional Facility on a cold December day, I see barbed wire, armed guards, and watchtowers. I still can't believe these biannual visits are my life, although nearly 12 years have passed since my mom was murdered. I'm patted down and stripped of my belongings, but not before I grab a few coins for the vending machines.

My first sight of my brother, Max, is behind a pane of glass. He's a good-looking kid — his clean-cut features call to mind a young Matt Damon. He's 28, but he looks about 18. "Prison preserves you," he says. "The absence of alcohol, cigarettes, and sun helps." The only changes I notice in his appearance are tattoos on his arms, knuckles, and forearms — blurred black letters and shapes, none in the form of recognizable words, that the inmates give one another in jail. I wonder what Mom would think of them. But then I remind myself Max is in prison for life — what would she say about that?

Just after 3 a.m. on October 3, 1999, our mother was stabbed 42 times in the face, neck, and chest, in the foyer of our home in a middle-class suburb outside Dallas, Texas. Police call an especially violent death like hers "overkill" — a crime of passion or rage, usually committed by someone the victim knows. That night, Max, then a rebellious 17-year-old high school junior, and his degenerate friends were strung out on cocaine and marijuana. They hadn't eaten for three days and were out of cash. So Max and his buddy Chris Brockman hatched a plan to steal money from our mom's purse. When they got to the house, the dead bolt was locked, and Max didn't have his key.

Although the boys' court testimony differed over what happened next, we know that Chris rang the doorbell, and our mom, a creative, self-sufficient woman who loved to make cookies from scratch and leave us handwritten notes, answered in her nightgown. She'd been searching frantically for Max that night — he'd begun leaving home and hanging with a tough new crowd for days at a time. At 10:30 p.m., she'd called a church friend of his--the last person she spoke to before the attack — asking him to tell Max he could come home anytime, day or night. Max probably never got that message, but when the doorbell rang a few hours later, she must have rushed to answer, relieved he was back. Even if she intuited something was wrong, she wanted him home, and probably assumed he'd just been drinking — certainly not doing drugs. But whatever she saw once she opened the door must have scared her. Police believe she turned to run as Chris flew into a rage, stabbing her in the skull with a pocketknife and yelling at Max to get more knives. After the murder, the boys threw the house into disarray to make it look like a robbery, stole her wallet, and used her ATM card to get cash at a local bank.

Reconstructing the events of the evening, detectives later concluded that my brother's role in the slaying was limited to handing Chris four kitchen knives. Max denied even that, claiming he was in the garage when Chris attacked her. But if so, how would Chris know where to get the knives? And how could he retrieve them in the middle of a brutal assault? At the trial, Chris corroborated that Max didn't physically hurt our mother. Chris was the only one covered in blood after the crime; I've never doubted that Max didn't stab her himself. (DNA evidence later proved he didn't.) But he didn't stop the murder or get help. Worse, the very idea to kill her might have been his in the first place: Chris testified that on the way to her house, Max had said, "If my mom sees you, you have to kill her."

That year, I was 25. At the exact time of the murder, 3 a.m., I awoke in my apartment in Birmingham, Alabama, 650 miles away. The entire right side of my body was numb. But I didn't learn about the murder until the next evening; while I prepared to host a dinner party, the news desk paged me. As a television reporter for the Fox affiliate in Birmingham, I was often interrupted for stories, but this time my office was relaying a phone message from a detective in my small hometown, Grand Prairie. When I reached him, the detective said they'd been called to my mom's house that afternoon. (Her fiancé, returning from a hunting trip, had found her body.) After years of interviewing people at crime scenes, I was now on the other side. But instead of becoming hysterical, I shifted into reporter mode and asked questions: Do you have a suspect? A weapon? Any leads?

I had no way of reaching Max — he didn't have a cell phone or credit cards, so when he'd vanished earlier that week, my mother hadn't been able to trace him — but I thought I'd see him at home. Not until I made the 11-hour drive later that night did I learn about his involvement. I dialed my mom's house, knowing detectives would answer. "We're issuing capital murder warrants for Max and Chris," one of them told me. "If you hear from Max, call the police. Do not help him, or we'll be issuing a warrant for you, too." The conversation was surreal; I felt stunned and numb. After learning my mother had been murdered, I felt like anything was within the realm of possibility, but I couldn't imagine Max having done something so horrible.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

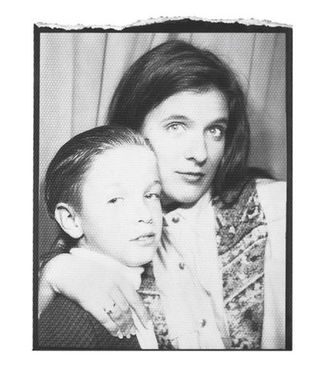

Max is eight years younger than I am. Our parents couldn't have kids and adopted me when I was 16 months; Max was 5 months when they brought him home. I remember everything about that day. We'd gone shopping, picking out Oshkosh overalls for him. When I came home from school, I had a baby brother! We were raised as siblings in a traditional suburban family, active in school and church. One night when Max was 8, my mother asked him to set the dinner table. I said it would be easier for me to do it, but she insisted, "Melissa, we're raising someone a husband." By high school, Max was a well-liked athlete who'd never gotten into any trouble worse than a few low math grades. Then, in 1998, our parents divorced and moved Max, a 16-year-old sophomore, to Shady Grove Academy, a private Christian school. My mother was concerned he was more of a follower than a leader with his friends, and thought, ironically, he'd be less likely to fall in with a bad crowd there, with smaller classes and more attention.

Shady Grove marked the turning point in Max's life. He joined the basketball team and befriended Chris, an unstable teammate who'd been kicked out of several schools and whom teachers saw as a ticking time bomb, thanks to a dangerous cocktail of illegal substances he combined with prescription medication for his bipolar disorder. By the next fall, Max had fallen in with a fringe group of misfits, Chris' friends from previous schools, and was missing classes and doing drugs.

When I was growing up, I had curfews and phone restrictions: My parents were very hands-on. Even after their divorce, my mom, who co-owned an upscale Dallas furniture store, and dad, a factory worker at Lockheed Martin, cooperated to rein Max in. My mom was independent, capable, and visionary when it came to interior design — she was decorating my Birmingham apartment in "shabby chic" before the term existed — but she was also extremely determined. She worked full time, and felt equipped to handle anything. That's what scared her about Max's sudden downward spiral. As he got caught up with this new group--a mix of high school graduates and dropouts with their own cars and apartments, who plied younger kids like Chris and Max with drugs and booze and then demanded money in return — she was at a loss. In the weeks before the murder, a counselor had advised my parents to use "tough love." I remember my mom saying Max couldn't be gone long: "He has absolutely no money. He has to come home."

Back in Texas, I took an active role in the investigation, pleading with the father of one of my high school friends, a detective on the police force, to retrieve the bank's surveillance footage the day after the funeral. Max had turned himself in after the body was found, and police had the evidence to convict both teens, but I needed to know who was at the ATM 40 minutes after our mom was murdered. When I saw Max on the tape, covering his head with a sweatshirt as he withdrew $300, I was stunned and disappointed. I desperately wished I was seeing someone with a gun to his head, forcing him to make the withdrawal. I couldn't believe he had taken the cash of his own free will — or that my mom had given her life for such an insignificant sum. Her assets and bank account were frozen, so it wasn't possible for us to pay for his defense, but even if it was, I'm not sure if I would have after seeing that tape. (Our dad, completely devastated, couldn't afford the fees.) So Max had a public defender.

I did buy him a suit and tie for the trial so he wouldn't have to appear in his jailhouse jumpsuit. I hoped that would help the jury see him for who he was: a good kid with a solid family. He was convicted of capital murder anyway. Max didn't kill our mother, but since he conspired with Chris to rob her, under the Texas penal code he was liable for the slaying, too. Both boys were sentenced to life in prison. I've always wondered if a more expensive attorney could've gotten Max a shorter sentence. Instead, he'll serve 40 years before he's eligible for parole in 2039, at age 57.

My dad and I held hands as the verdict came down and, in one moment, the jury defined my brother's life — and our family's. Anger, shock, and devastation pulsed through me as I realized Max's life, as he'd known it, was over. Although I hadn't been able to pay for his defense (and besides, there were too many unknowns around the crime, and I'd wanted to digest all of the evidence revealed in the trial for myself), I thought his punishment was too harsh. He got the same sentence as Chris, who, in a chemical frenzy, literally sat on top of my mom, stabbing her to death. Am I living in a nightmare? I kept wondering. Will I ever wake up? Still, I'd promised Max I would be there throughout the trial--and I was, every day. And despite my disappointment, the verdict and sentencing were also a relief after months of testimony.

According to the social workers on Max's case, criminals don't usually process their crimes for at least five years. You can try talking to him, they said weeks after the murder, but you won't get the truth. Still, I was obsessed with knowing what had happened. One night, in a desperate attempt to understand how our mom felt as she died, I went to the kitchen, got a knife from the drawer, and held it to my flesh. I was tempted to penetrate my skin and share in her suffering. For the first year or two after her death, I was absorbed in logistics: the crime, the trial and sentencing, and issues around her estate. (Only 51 when she died, she didn't leave a will.) I didn't truly process my rage and sorrow until six years later, when I went on a trip to Australia — alone, after some friends bailed out. One morning, at a bed and breakfast in the Hunter Valley wine region, I woke up suffocating with grief, feeling the despair, deep pain, and presence of pure evil around the crime as strongly as if it had just happened. I cried like never before; overwhelmed and unable to sleep for a desperate 24 hours, I felt like I was being tortured. When I returned home a week later, I learned that just hours after I'd woken up in despair in Australia, Chris had killed himself in prison.

I followed the social workers' advice, and in the years immediately after the murder, Max and I rarely discussed it during my visits. When we did, he denied his involvement, saying he didn't belong in jail. Seven years after the murder — five years ago — when Max again insisted he didn't kill our mother, I said, "You're not spending your life in prison because you physically murdered someone. You betrayed your family. You brought a maniac into our house, and you didn't fight back." He hadn't intended any of it, he replied: "It was a series of bad decisions — skipping school, doing drugs, hanging out with the wrong kids, going to get money in the middle of the night."

Those decisions robbed me of my mother and my brother. I just got engaged, and I want my fiancé to meet Max, but I'm not sure about my unborn children. I do want them to know about my family, however. Some of my fondest memories are from the three-week camping trips we took every summer, when my mom would pack the car with homemade goodies and whip up gourmet meals out in the wilderness on a propane stove. We visited 46 states by the time I was 16, Max and me in the backseat as we drove, giggling and playing car games.

I'm still in the process of forgiving Max. Therapy helped, and then, seven years ago, I got involved with Priority Associates in New York, a Christian organization that connects young professional. I started building strong friendships with the women I met there, so I did what I thought my mom — who had a cadre of lifelong friends — would do and organized a weekly breakfast for us. Seeing the group members struggling with their own issues allowed me to be honest about what had happened in my family without fearing judgment, and I started healing as I talked about it. In 2008, our small group grew into a nationwide network, PURE, which hosts conferences where women can meet, network, share their stories, and reflect on what matters most. (To learn more, visit thepureconference.com.)

Back in the prison, staring at Max through the glass, I struggle for common ground. I start by asking what he misses most about Mom's cooking. We agree on her desserts — chocolate peanut butter squares and magic cookie bars — then laugh and glance at each other as if we share a secret no one else knows. My mom always wanted to give us a childhood full of great memories, saying, "When you're 80 and looking back on life, it's not the things you owned or the house you lived in; it's the places you went and the people you were with you'll remember." So many years later, though our lives are changed forever, Max is still my brother. And although I don't know what lies ahead for us, Mom was right about the past. It's the people I remember — the people we were.

-

Anne Hathaway Details the "Gross" Audition Request She Once Endured

Anne Hathaway Details the "Gross" Audition Request She Once Endured"Now we know better."

By Meghan De Maria Published

-

The Emotional Ending of 'Baby Reindeer,' Explained

The Emotional Ending of 'Baby Reindeer,' ExplainedNetflix's latest miniseries from Richard Gadd is based on the true story of the comedian and his stalker.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

The Must-Visit Hair Colorists in New York City

The Must-Visit Hair Colorists in New York CityI trust these talented colorists implicitly.

By Sophia Vilensky Published

-

Of Murder and Motherhood

Of Murder and MotherhoodTheir children are gone but these women are united in their fight for justice and answers.

By Katya Cengel Published

-

60 Gifts for Mom She'll Truly Love

60 Gifts for Mom She'll Truly LoveFrom creature comforts to luxe indulgences.

By Sara Holzman Published

-

'Skye Falling' Deserves a Spot on Your Summer Reading List

'Skye Falling' Deserves a Spot on Your Summer Reading ListIn July, Marie Claire read Mia McKenzie's 'Skye Falling.' See what the #ReadWithMC community thought about the book here.

By Marie Claire Published

-

Adria Biles, Simone Biles' Sister, Is a Former Gymnast and Simone's Biggest Fan

Adria Biles, Simone Biles' Sister, Is a Former Gymnast and Simone's Biggest FanSimone Biles' little sister, Adria Biles, is a fellow gymnast, a Simone lookalike, and a fierce champion of her famous sister.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Melissa Moore's 'Life After Happy Face' Podcast Looks at Killers Through New Eyes

Melissa Moore's 'Life After Happy Face' Podcast Looks at Killers Through New EyesThe true crime expert and daughter of the Happy Face Killer opens up to Marie Claire about destigmatizing the label of 'criminal's kid.'

By Maria Ricapito Published

-

Won't Call the Midwife

Won't Call the MidwifeWith high rates of maternal mortality and coercion in hospital settings, more American women are exploring childbirth without any medical assistance whatsoever. The Free Birth Society provides community, resources, and validation for these convention buckers. But experts warn that choice comes at the expense of safety.

By Rebecca Grant Published

-

Michelle Zauner's 'Crying in H Mart' Is Deeply Moving

Michelle Zauner's 'Crying in H Mart' Is Deeply Moving"She made me want to eat and cry at the same time..."

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

Being Estranged From My Mom Is Hard. Mother’s Day Makes It Harder

Being Estranged From My Mom Is Hard. Mother’s Day Makes It HarderIt’s high time to start representing the different types of mother-daughter relationships—or lack thereof—that exist during the holiday.

By Christina Wyman Published