The most memorable Valentine's Day gift I ever received was a black nylon fanny pack designed to hold a gun. For my live-in, gun-nut boyfriend, it was a grand romantic gesture and an encore, of sorts, to his Christmas present, a .22-caliber semi-automatic pistol. I had hoped for the new "lady friendly" hammerless Smith & Wesson .38 revolver, but the fanny pack would have to do.

It definitely topped his gifts from years past: a can of pepper spray and a tactical pocketknife. And the timing was perfect. I had just qualified for a concealed-handgun permit under a recently passed state law-the state, of course, being Texas.

Every time I jogged in our neighborhood, a safe place by most standards, my boyfriend checked to make sure I had my gun with me. The fanny pack had a special Velcro strap inside so the firearm wouldn't jostle or go off as I ran, although sometimes it bruised my hip. And yes, I occasionally wondered if it was necessary to pack heat for an afternoon run. But I continued to do so -- and even began carrying it in my purse. I was pretty sure I'd have the guts to use it if I had to. When I worked as a club doorgirl, I once maced a guy because he was banging my boss's head on the sidewalk. It was that very night, in fact, that my boyfriend first asked me out.

On one of our first dates, we tried out his brand-new AK-47, outfitted with a rapid-fire mechanism and a 30 round drum. Clad in a 1960s leopard coat and knee-high boots, I squeezed the trigger and heard the rat-tat-tat sound of bullets spraying out, pelting the sides of the rock canyon and echoing back at us. Our other dates included shooting cardboard human-form targets at indoor gun ranges and attending gun shows after Sunday brunch.

For me, there was nothing weird about living among heavy artillery and having to move night-vision rifle scopes from the table before serving dinner. I grew up in the suburbs of Dallas with a rabidly Democratic stepfather who nonetheless believed that guns should be stowed in every car, crevice, and corner. The nail-polish drawer in my parents' bedroom contained a .357 Magnum alongside the cuticle scissors. A cupboard over the stove housed a holster with a wooden grip peeking out. Going out to dinner always involved my stepdad giving my mom a pistol to keep in her beaded baguette purse. He put NRA stickers on the family cars, including mine. Pistols were everywhere, and although it seemed archaic, paranoid, and even somewhat, shall I say, Branch Davidian, I got used to being within three feet of loaded firearms at all times.

In my early 20s, I applied to the Dallas Police Department. And though I ended up finishing college instead, I had been ready to go to work every day knowing I might have to kill. Being a woman with a gun gave me power and strength in a throwback environment where females were viewed, defiantly, as the weaker sex. The "good old boy" system in Texas assured that men could climb the workplace ladder with relative ease, while women -- subjected to pet names like "little lady," "honey," and "darlin'"-- were regarded as nothing more than secretaries and glorified coffee servers (even when they were executives or lawyers). As a woman in Dallas, I was bombarded with giant highway billboards advertising strip club after strip club. I often felt that, given my state's narrow view of women, I'd never gain the same credibility bestowed upon a man. And I was already on the fringe, favoring vintage frocks over low-cut tees and Bettie Page bangs over big hair and fake nails.

But while my ability to compare the recoil between a .44 and a .45 gave me something in common with the Bubbas, it also sent the message that I was not afraid to be strong. Packing a gun made me feel like a law-abiding version of Thelma or Louise. The power was exhilarating, something I couldn't find through any other means.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Lots of American women apparently feel the same way. Enrollment in the NRA's "Women on Target" program-which involves shooting instruction, hunting trips, and marksmanship -- rose to more than 6000 in 2006, a big jump from the 500 women who participated in 2000. And gun manufacturers are responding to this fast-growing demographic by making smaller models that better fit in women's hands. Websites that specialize in gun gear are adding lady-targeted accessories, highlighting Kelly-style bags with side-entry holster compartments and faux day planners meant for lead-loading-like the cheekily monikered "Hidden Agenda." In pro-gun circles, the term "security mom" has replaced "soccer mom," evoking a new breed of maternal type with a "locked and loaded" mentality. It's something I can relate to. I was always imagining who might be waiting for me in the parking lot, or whether I could reach my gun with a bag of groceries in my hand. My boyfriend relished the feeling of imminent danger, insisting on wearing tactical batons and mace on his belt loops-even at weddings-and choosing aisle seats at the movies "in case someone busts in and attacks us."

But though guns were a staple of my life, I was put off by almost anything else "Texan." I worked in a store selling stilettos to drag queens. Rather than rodeos, I went to rockabilly shows. You wouldn't catch me dead wearing cowboy boots; I was all about Doc Martens. Barbecue repulsed me, and wide-open spaces made me wonder where the shops were. Politically, I was an outcast, supporting a woman's right to choose, gay marriage, and, yes, background checks for gun purchases.

I always knew I was meant to live in a liberal city (and dump that defensive boyfriend), so eight-and-a-half years ago, I accepted a job as a paralegal at the Manhattan district attorney's office, which offered an interesting segue from the Wild West. I talked guns with the officers, who were amazed that a woman knew her Rugers from her Lugers. I kept my gun license in my wallet for show-and-tell, even though it wasn't valid in New York state.

My gun knowledge was a novelty to my fellow paralegals, mostly women who came from Connecticut, New Jersey, and Long Island. I'm not sure if it was the widening of their eyes when I told stories about shooting, their nervous laughter, their sidelong glances at each other, or all three, but I began to realize that my experiences with weapons were not exactly the norm. I began to feel like a caricature, as if I belonged in a Coney Island sideshow as "the rootin' tootin' Texas gun lady." Although there were a couple of assistant DAs who liked to talk guns with me, no one who worked in our bureau carried one-not even those who were prosecuting gang members and drug dealers. This Northeastern approach to law enforcement-tough, but without the need to boost cojones with caliber-began to shift my view on guns. Visiting Dallas didn't hurt either.On one of my first trips back to the Lone Star State, I brought a native New Yorker I was dating (who would become my husband two years later). Within 20 minutes, my stepdad had him slamming shots of tequila and shooting beer cans with a BB gun in the backyard. When we borrowed the family car, I remembered to remove the pistol from the glove compartment, since my carry license was no longer active. We later realized there'd been another gun under the passenger seat all along-the semiautomatic that, at the time, my parents thought they'd lost. This wouldn't have fazed me before; now it felt dangerous and weird. Though I desperately missed the big Texas sky, the sweet smell after a storm, and even the barbecued brisket, the rest of the state started to feel like a lawless theme park with SUVs, stadium-size churches, and billboards advertising upcoming gun shows and reminding parents that "children under 12 are admitted free!"

Because I'd always had guns, I always thought I needed them. Now, having spent most of my adult life unarmed and living in New York City-squashed between strangers on the subway without confrontation, counting a full cash drawer alone at night in my basement boutique without incident after I left my job with the DA, and living through the aftermath of September 11th, when the aware-ness of mortality and the fragility of life became part of daily consciousness-I'm more compassionate. It's a huge change from the well-defended person I was in Texas, or the homesick Second-Amendment fanatic I became in New York, the one who voted for George W. Bush in 2000, partly because he was Texan and knew what Ranch Style Beans were. It's a vote I deeply regret, given his "Quick Draw McGraw" way of dealing with the world.

Recently, my sister called to report that she, along with the rest of the family, had aced the concealed-handgun course. Despite having never fired a gun, she got a near-perfect score on the shooting test. Part of me wanted to roll my eyes at the idea of the entire family cleaning their guns together on a Sunday afternoon. Then I recalled the empowering feeling of passing the test myself a decade earlier. And although in that moment I sort of longed to be home on the gun range, wearing noise-canceling earmuffs, clicking the magazine into the butt of a gun, and chambering the first round just to see if I could still do it-I realized I no longer needed a gun to feel powerful. If anything, my willingness to be vulnerable makes me stronger. My newfound ability to live in the moment, rather than in perpetual, agitated anticipation-and dread at maybe having to put a bullet into someone-gives me more joy.

There's a well-known saying in the pro-gun world: "It's better to have it and not need it than to need it and not have it." I understand why that makes sense-as long as it's referring to umbrellas and tampons. As for a gun, I've come to believe that not having it and not feeling like I need it is, by far, the best way to be.

-

Bitten Lips Took Center Stage at Dior Fall 2024 Show

Bitten Lips Took Center Stage at Dior Fall 2024 ShowModels at the Dior Fall 2024 show paired bitten lips with bare skin, a beauty trend that will take precedence this season.

By Deena Campbell Published

-

30 Spring Items That Solve My Expensive-Taste-on-a-Humble-Budget Dilemma

30 Spring Items That Solve My Expensive-Taste-on-a-Humble-Budget DilemmaSee every under-$300 spring item on my wish list.

By Natalie Gray Herder Published

-

Your Makeup Won't Budge With These Setting Sprays

Your Makeup Won't Budge With These Setting SpraysPrepare for 12-hour wear.

By Sophia Vilensky Published

-

Racist Photo Sent in Wake of Sorority Rush at University of Alabama

Racist Photo Sent in Wake of Sorority Rush at University of AlabamaUniversity of Alabama and national chapter of the sorority in question are investigating image captured from social networking site.

By Kayla Webley Adler Published

-

This Act Could Put an End to Anti-Abortion Legislation

This Act Could Put an End to Anti-Abortion LegislationWomen's right to choose is constantly at stake—but this might the solution.

By Diana Pearl Published

-

Yet Another Blow to Birth Control Coverage

The Supreme Court's latest decision will limit a key benefit for women.

By Laura Cohen Published

-

California Audit Finds Universities Are Failing Students Who Are Sexually Assaulted

California Audit Finds Universities Are Failing Students Who Are Sexually AssaultedState auditor report says colleges must do more to prevent, respond to, and resolve incidents of rape and sexual assault on campus.

By Kayla Webley Adler Published

-

Sexual Assault Survivors Speak Out Against Campus Rape

Sexual Assault Survivors Speak Out Against Campus Rape"This is the civil rights movement of our generation"

By Allison Ellis Published

-

College Professors Say They're Being Punished for Speaking Out Against Rape on Campus

College Professors Say They're Being Punished for Speaking Out Against Rape on CampusInstructors at several schools say when it comes to sexual assault on campus, many on campus would rather they stay out of it.

By Claire Trageser Published

-

These Women Graffiti Artists Are Making People Talk in Egypt

These Women Graffiti Artists Are Making People Talk in EgyptMove over, Bansky.

By Melissa Bykofsky Published

-

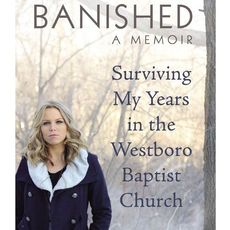

My Life in a Cult

My Life in a CultAuthor Lauren Drain speaks out about picketing U.S. solders' funerals and praising the terrorist attacks of September 11 as a teen member of the notorious Westboro Baptist Church — and about how her parents disowned her for questioning the group's shocking tactics.

By Lauren Drain Published