Who doesn't have a surreal tale about wrestling over the phone with a foreign-sounding agent as far away as Mumbai about some exceedingly local problem—like a surcharge on a cable bill? Now, as everyone's feeling the economic squeeze, Indian customer-service reps have become the new shrinks.

On a 90-degree night in Bangalore, India, a young woman named Purbani Mukherjee settles into her workstation to talk personal finance with customers across the globe, most of them in America. She answers nearly every caller—from jobless factory workers in Pittsburgh to Manhattan party girls with maxed-out credit cards—with the same soothing mantra: "I'm real sorry to hear that. How may I help you?"

Mukherjee, 26, a business-school graduate in a black cotton top with silver stitching, works at 24/7 Customer, one of India's top call centers. Located in a manicured business park—surrounded by towering walls to keep out the urban chaos—the company employs 2000 agents, a third of whom are women, to provide customer service and telesales for U.S. banks and corporations. The night shift is the busiest time, since the day is just beginning in America. In the main operations room (a wide-open space with low ceilings, not unlike the one in Slumdog Millionaire), hundreds of young, ambitious Indians wear headsets in row after identical row, their voices a purposeful collective hum.

PHOTO GALLERY: Inside Indian Call Centers

With many major U.S. companies, including American Express, Dell, and Verizon, outsourcing telephone operations to India, call-center agents are a symbol of our globalized age. And yet, with the economy in crisis and phone calls often motivated by palpable desperation, call-center agents are now playing the role of therapist, confidant, scapegoat—and lightning rod.

"We've all been surprised by how fast people's lives have unraveled," says Mukherjee, adding that callers frequently dissolve into tears. "The other day I spoke to a man in the Midwest who owns a failing transport company. He'd spent all his money on a big house and car, luxury holidays, and lavish presents for his kids," she says, shaking her head. "Now he's in deep, deep debt. I tried to discuss his financial options, but he was inconsolable. He just broke down, sobbing, 'I don't know what to do. I don't know what to do.'"

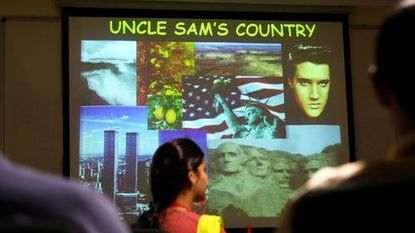

For newlywed Mukherjee, who earns around $3000 per year (a high salary for a young Indian urbanite, yet a mere one-sixth of the average call-center wage in the States), such tales are a bizarrely intimate insight into the downside of the American Dream. She admits that she always thought of the U.S. as a place with "a never-ending supply of money and material possessions," where crises are solved by Bree Van de Kamp turning up on the doorstep with freshly baked muffins. So did most of her colleagues. Indeed, call centers are renowned for emulating and idolizing U.S. culture. At 24/7 Customer, agents learn to speak with fake American accents and adopt Anglicized names like Kate and Ben. They attend crash courses in American history and study staples of Americana like Friends and The Apprentice. 24/7's lobby says it all: The walls feature murals of smiling call-center agents, dressed in the casual, geek-chic fashion of Silicon Valley hotshots, alongside giant corporate slogans. We are a highly motivated, performance-driven organization, says one.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Yet their foreignness is a sticking point, and culture clashes are rampant—as when Americans ask the Indians if they travel to work on a bullock cart, or kiss their boss's feet every morning; call-center employees are frequently hit up for a good curry-chicken recipe.

The agents' lilting tone seems to invite a measure of intimacy. Mukherjee recently talked to a distraught 80-year-old New Jersey woman whose son, on whom she was financially dependent, had just lost his marketing job. "After I'd answered her original query, she talked on for 15 minutes," Mukherjee recalls. "I sympathized as much as I could." Agents are trained to use stock phrases to end calls with talkative customers, such as "I must let you go, sir/ma'am," but sometimes, says Mukherjee, "you can't cut people off." Since the recession hit, many call centers are reporting that the average time spent on each call has doubled.

Of course, the flip side of this need to share is unchecked rage—at being out of work, at jobs being outsourced. "People often get angry when we can't do what they want, such as raise their credit limit," says Mukherjee. "Then they abuse us for being Indian and demand to speak to an American." In fact, so many customers are accusing Indian agents of "stealing American jobs" that some call centers have begun training agents in how to cope with the new fury. "Some people really shout and scream that we should give the jobs back," says Mukherjee, who does yoga in her spare time to relieve the stress of the job. "The main thing is to remain super-calm and never to take anything personally," she adds serenely, brushing her shoulder-length hair away from her face.

Downstairs in a boxy training room, Rohini Poonacha, 30, wearing a crisp blue shirt and a diamond stud in her nose, confirms that dealing with "aggressive callers" has become the greatest source of anxiety for employees. Poonacha is a 24/7 trainer who teaches accent and customer-service skills. "We do role-play and mock calls, where we cry and yell as hard as we can so trainees get used to it," she says. All calls are monitored, and agents are forbidden from losing their cool. "A raised voice conveys agitation, which is bad for business," says Poonacha. "If an agent's pitch goes up once, they're warned. If it happens twice, they're fired."

Not every employee can handle the pressure. Last September, a 23-year-old male call-center agent in Mumbai suffered a heart attack, induced by work-related stress, said doctors. A growing proportion of the nation's 300,000-strong army of call-center agents are reportedly suffering from other ailments, too, including obesity, back pain, insomnia, and stomach disorders. Still, in a country where women are struggling to break out of their traditional homebound, no-pay roles, it's an attractive gig. At 24/7, 15 percent of senior managers are female. "Outsourcing is a good industry for women," explains Shalini Kalra, 33, a supervisor with a clipped British accent. "It's totally performance-oriented, so you're judged on results, not gender." An engineering graduate, Kalra has worked at 24/7 for eight years. She's the first woman in her family ever to have a paid job; her mother thought her desire to work was "a passing phase." By now, she has earned enough at the company to buy her own modern apartment, where she lives alone. This is beyond rare for an unmarried woman in India. "I cherish my independence," she says. "I've earned it." The downside? Kalra averages 14 hours a day in the office. She says finding time to go on dates is "my biggest challenge, to say the least."

As for India's $11.5 billion outsourcing industry, the big challenge is in meeting the ever-growing demand for its cheap, educated workforce. Ironically, rising wages and a shortage of skilled labor in India are prompting some companies in the land of outsourcing to outsource elsewhere. Tata, India's largest corporation, which makes everything from trucks to jewelry, already has call centers in the U.K. So will jobless Pittsburgh factory workers soon be going by names like Rohini and Purbani, and fielding calls from Mumbai?

Abigail Haworth is MC's senior international editor, based in Bangkok. She also wrote "My Girlfriend's Secret Life"

-

Anne Hathaway Details the "Gross" Audition Request She Once Endured

Anne Hathaway Details the "Gross" Audition Request She Once Endured"Now we know better."

By Meghan De Maria Published

-

The Emotional Ending of 'Baby Reindeer,' Explained

The Emotional Ending of 'Baby Reindeer,' ExplainedNetflix's latest miniseries from Richard Gadd is based on the true story of the comedian and his stalker.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

The Must-Visit Hair Colorists in New York City

The Must-Visit Hair Colorists in New York CityI trust these talented colorists implicitly.

By Sophia Vilensky Published

-

The Best Bollywood Movies of 2023 (So Far)

The Best Bollywood Movies of 2023 (So Far)Including one that just might fill the Riverdale-shaped hole in your heart.

By Andrea Park Published

-

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ 2023: Everything We Know

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ 2023: Everything We KnowCue up Mike Reno and Ann Wilson’s “Almost Paradise."

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

Who Is Gerry Turner, the ‘Golden Bachelor’?

Who Is Gerry Turner, the ‘Golden Bachelor’?The Indiana native is the first senior citizen to join Bachelor Nation.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

‘Virgin River’ Season 6: Everything We Know

‘Virgin River’ Season 6: Everything We KnowHere's everything we know on the upcoming episodes.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

The 60 Best Musical Movies of All Time

The 60 Best Musical Movies of All TimeAll the dance numbers! All the show tunes!

By Amanda Mitchell Last updated

-

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We KnowNetflix owes us answers after that ending.

By Zoe Guy Last updated

-

35 Nude Movies With Porn-Level Nudity

35 Nude Movies With Porn-Level NudityLots of steamy nudity ahead.

By Kayleigh Roberts Last updated

-

The Cast of 'The Crown' Season 5: Your Guide

The Cast of 'The Crown' Season 5: Your GuideThe Mountbatten-Windsors have been recast—again.

By Andrea Park Published