Taylor Hirth and I are curled up on a leather couch at the home of her friend in Kansas City, Missouri. It is late afternoon, and the only light in the room is from the television playing a tape of Taylor, now 31, sitting in a police interview room. I watch her as she scrutinizes every word and movement on the screen. Is there something that she didn't say right? Is she remembering all of this correctly? Could she have done something differently? She asks herself these questions all the time.

The date of the recording is Feb. 10, 2016, 11:05 a.m.

Sometime after 1 a.m. on Feb. 9, 2016, the door of Taylor's apartment was pushed in and she was gang-raped in her own bed in the Kansas City, Missouri, suburb of Independence while her then-2-year-old daughter slept by her side.

For hours, the men took turns raping her. At least, as she tells a detective of the Independence Police Department (IPD) in the video, she thinks it was three, it's possible there were more—she was facedown in her pillow for part of the time. Later, the men put her pajama pants over her head, lifting them only to ejaculate on her face. She tells the detective about waking up and realizing a man she didn't know was standing in her bedroom doorway. Before she could sort out what was going on, he ordered her to roll over on her stomach. She screamed, but he jumped on top of her and told her if she screamed again, he would hurt her and her daughter. And then he started raping her. And then he told his buddies to join in.

"At one point, my daughter woke up," Taylor tells the detective. "I could tell she was sitting up, and I was trying to feel if it was another person. I wanted to make sure no one was near my daughter, that no one was touching her, and I reached up and felt her face and could tell she was there, and she held my hand while they raped me repeatedly and she was watching."

"This is the part that always gets me," Taylor tells me as she watches herself crying on screen.

"I was so proud of her for just laying there and being quiet," she tells the detective. "I was at the point where I was trying to be as calm as possible and take on the persona of somebody who was enjoying what they were experiencing, so whatever she saw, I wanted her to feel safe and feel like Mommy is okay, Mommy wasn't being hurt, so I held her hand, and I said, 'It's okay, honey, these are nice men. Mommy's just playing with these men. Okay, baby, lay back down and go to sleep."

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

It is the only time during my five days in Missouri I saw Taylor almost cry.

After the attack, Taylor—unable to find her cell phone—posted a message on Facebook saying she had just been raped and begging anyone online to send the police to her address. By chance, one of her good friends logged on about 20 minutes later. The friend called the police, and then joined Taylor at the hospital for support but also to take care of Taylor's daughter while Taylor underwent a SANE (Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner) exam.

Six months later, on Aug. 31, 2016, IPD closed Taylor's case, with the detective assigned to her case explaining in his report that "all investigative leads have been exhausted." Though the vaginal swabs done during her exam indicated male DNA, IPD hadn't found a match. "If additional information becomes available, the case will be re-opened at that time," the report stated.

So Taylor went back to her life as a working single mom. She tried to reestablish some normalcy, if not for herself, for her daughter. But, she told me, her daughter can sense something with mom is "off." Taylor moved into a new apartment, and she sleeps with her daughter in her bed, bedroom door closed and locked, a Taser hanging nearby. Even if her attackers had been caught, chances of a conviction were slim. But four months after IPD closed her case, new information came to light and Taylor's case was reopened. One man has now been charged. (He has not yet entered a plea.) I asked Taylor if she was hopeful in light of this development, and she said she wouldn't use that word. Some days she feels empowered, determined to keep speaking up on behalf of herself and victims everywhere, and other days she feels hopeless, convinced that her efforts have been futile and that the guys who raped her will never be punished. This is the story of one young woman's attempt to get justice, only to experience firsthand why so many victims of sexual assault don't think it's even worth reporting the crime to the police.

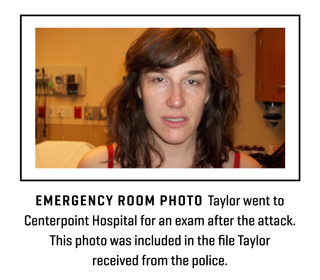

Taylor underwent a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) exam at Centerpoint Hospital after the attack.

According to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), 2 out of 3 sexual assaults go unreported. The first reason is fear of retaliation by the assailant. The second is victims of sexual violence believe the police would not do anything to help. "Ultimately, police are the largest obstacle to the prosecution and conviction of rapists in the United States," Kansas University law professor Corey Rayburn Yung wrote in a 2016 analysis "Rape Law Gatekeeping." "Police disbelieve rape victims far more often than the public and other agents involved in rape investigations." Yung explains that, as a result of strong cultural biases against victims of sexual assault, police do not fully investigate the crime and that allows rapists to go free, thinking they can get away with additional sexual violence in the future. Taylor believes her case exemplifies the horrific way this can play out.

Even as she was being assaulted, Taylor knew she would report this crime.

"I knew I was going to fight these guys tooth and nail," she told me. "I thought, Fuck this, they messed with the wrong chick."

But, she added, some of that anger and focus on getting justice was a means of self-preservation.

"Part of that thinking was me trying to keep my head away from the possibility I wouldn't make it out alive," she said.

Taylor has always been a feminist and a victim advocate. She worked at Planned Parenthood as an intern in 2009 recruiting volunteers and at a domestic violence shelter from 2012 to 2014, but her advocacy is informed by personal experiences as well. In 2010, Taylor was an intern for state Rep. Paul LeVota, D-Independence. Taylor said he started pursuing her with suggestive text messages, asking her over to his apartment—alone—for drinks. When she refused, he continued to try to coax her to come over with a barrage of texts. In July 2015, Taylor broke her silence and spoke to theKansas City Star after a Senate investigation released details of other sexually charged texts LeVota sent to an intern. Two days after the story broke, LeVota, who was by then a state senator, announced he would resign his seat. He denied the allegations related to the investigation and denied that he acted inappropriately with Taylor.

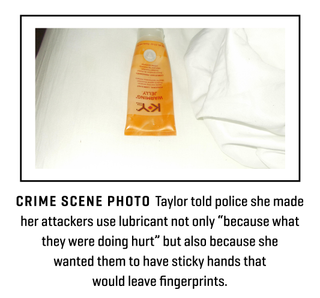

Taylor knew how hard it is to get a conviction in an assault case—according to RAINN, out of 1,000 rapes, 994 perpetrators will go free—but she also knew that in order for law enforcement to have a better chance of catching these guys, her assailants would need to leave as much evidence as possible. During the attack, Taylor made the men use lubricant not only "because what they were doing hurt," she tells the detective in the taped interview, but also because she wanted their hands to be sticky to leave obvious fingerprints. At one point when one man tried to force his penis into her mouth, she protested saying her mouth was so dry—could he get her a glass of water? They would have to touch glasses, cabinets, and the kitchen faucet.

Taylor tells the detective she saw an opportunity to escape once during the assault, when she thought the guys' pants were around their ankles. She tried to lunge across the bed to grab her daughter, but as soon as she made a move in that direction, she was grabbed and punched in the back of her head and side and bent back over the side of the bed. One of the attackers, she reported, warned her if she did that again, he would punch her and her daughter. After that, she told me, she resigned herself to taking it. She didn't look at her attackers, she played along, she said she wanted to make them feel "this chick is okay, she isn't going to call the cops."

When it was over, Taylor did everything "right." She notified the police. She kept the bra and panties they pulled off her—she couldn't find the pants. She didn't shower so the dried semen would remain on her thighs, her belly, her face, knowing she had to preserve the DNA for the SANE exam.

Taylor herself gives the detective possible leads during her recorded interview Feb. 10. She mentions hearing noises from downstairs after the assault, she talks of a company whose workers may have had access to the building and says someone had recently written something like "You Sexy" in the dust of her windshield in the apartment parking lot. She also mentions that one of the men said it was another's birthday the day of the attack and that she heard one of her attackers calling another by name. She wasn't 100 percent sure what it was, but she gives the detective three similar-sounding names that she might have heard.

Still, from the moment the first patrol officer arrived, Taylor began to doubt that she'd actually get justice. About 20 minutes into her taped interview with the detective, after she has given her account of what happened and answered his questions and follow-up questions, he asks about what she did earlier on the night of the attack, and if she is on Tinder or other dating websites that might lead someone to know who she is. The Taylor on the TV politely shakes her head no.

But as we watch the video, the Taylor next to me on the couch is furious. "Tinder! Tinder! What the fuck is it about these fucking guys and Tinder!" It isn't just about the Tinder questions, Taylor told me. It's that she felt like a criminal in her own home, wrapped in a robe, holding her child.

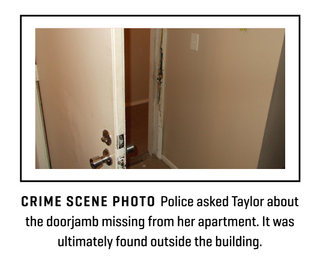

As she tells the detective in the interview, she was appalled by the way she was treated when two male officers arrived at her apartment. "The first thing he said to me when he walked in was, 'So, what happened here?'… as if I was a party to something, that this was somehow something that I invited," she tells the detective. That officer, too, asked her about Tinder, she says, and then he was preoccupied with where the missing part of her doorjamb was. The detective explains that they have to ask about things like Tinder because it's very popular and they've had situations where "there's a plan to meet and it ended up turning into a rape." Sometimes, he says, people are too embarrassed to reveal they were on a dating site, even though it can be important.

Taylor says she understands that but still objects to the officer's accusatory tone, but the detective cuts her off mid-sentence and quickly refocuses on the doorjamb.

"Of all the burglaries I've worked, of all the burglaries [the responding officer]'s ever worked, we've never once, ever seen or heard of a suspect cleaning up the mess from a doorjamb," he tells her. "They'll wipe down their fingerprints or anything like that, but they don't pick up messes from the doorjamb. And if they are trying to cover their tracks that much, they're not going to leave—we found sperm on your bed—they're not going to leave actual DNA but take a doorjamb." He says he's just trying to make sure she didn't forget anything.

About two minutes later, he tells Taylor that he believes something happened—he talked to the nurse who told him of extensive damage—but "what I just want to make sure of—and I want you to feel comfortable—if for some reason, and I'm not saying there was, please don't think I am, but I just have to ask this, if for some reason you had a guest over, and then it got out of control, and you're trying to cover for somebody, I just want to make sure that..."

"No," Taylor says, offering for him to look through her phone or any of her records. Later in the interview, he has Taylor sign a release to check her phone. Then he asks if she's gone back to the apartment since the attack. Taylor hadn't. He asks her if she locked the door when they took her to the hospital. She tells him she left in the ambulance before the cops left. The detective briefly leaves the room and, when he returns, has Taylor sign a consent form allowing crime scene investigators to go into her apartment.

At that point, it had been over 30 hours since the rape.

Taylor went to the Independence Police Department in Jackson County, Missouri, the day after her rape for an interview with a detective.

The distrust between sexual assault victims and police officers is well-documented. In August 2016, the Department of Justice released a scathing report on the Baltimore Police Department, which found that the BPD Sex Offense Unit questioned victims "in a manner that puts the blame for the sexual assault on the victim's shoulders" and inferred victims were responsible because they "engaged in behavior that invited the assault." The report also noted that "victim advocates reported that BPD's Sex Offense Unit was only minimally investigating reports of sexual assault; for example, they were not making efforts to identify witnesses or submitting rape kits for testing."

In a 2014 analysis, "How to Lie With Rape Statistics: America's Hidden Rape Crisis," Corey Rayburn Yung, the Kansas University law professor, points to investigations in New Orleans, Philadelphia, and St. Louis that found police departments undercounted reported rapes, either by "designating a complaint as 'unfounded' with little or no investigation; classifying an incident as a lesser offense; and, failing to create a written report that a victim made a rape complaint." He notes that police may face political pressure to manipulate crime statistics, but he adds, "Police operate within a larger cultural framework that is hostile to the stories of rape victims. These attitudes infect police work such that police often disbelieve rape victims and, as a result, do not include complaints within official police records used to compute crime statistics."

In 2010, Martin D. Schwartz, a sociologist and research fellow at the National Institute of Justice (part of the DOJ), released the results of a study he conducted between 2004 and 2006. The researchers asked patrol officers what percentage of the time they have a "gut feeling" that a rape never happened. Of the 428 respondents, 32.7 percent estimated that all of reported rapes are false. The true number of false reports is between 2 and 10 percent.

Shortly after IPD closed the investigation of Taylor's case, she requested her full file and, she told me, received what she understood to be everything pertaining to the investigation of her case: 43 pages of information, her taped interview with the detective, and photos the police took – all of which she provided to me to use in my reporting. Only eight of those pages were about the police investigation of her case. The remaining ones were from the nurse and laboratory. Two pages from another woman's sexual assault report were also mistakenly included.

The Stoneybrook apartment complex, where Taylor lived at the time of the rape, is made up of four buildings with 12 apartments per building. According to the police report, two detectives canvassed the neighborhood on Feb. 10 beginning at 2:30 p.m. and contacted all the apartments in Taylor's building. In the middle of the afternoon on a Wednesday, only two people were home. Neither indicated they heard or saw anything. The report then states that the detectives made contact with the property manager and she told them that "to her knowledge all of the apartments in building 17007 are occupied."

In the files that the police gave Taylor, there's no mention of the detectives obtaining a list of current residents to check their names against the names Taylor provided to the detective in her interview at the police station or visiting the other buildings in the complex. The report states the officers said they would return later in the evening to try to contact more residents, but the only mention of the return visit is to one apartment across the hall from where Taylor lived. There is no indication IPD contacted the company whose workers may have had access to the building that Taylor had mentioned to the detective in her interview. I went to Stoneybrook twice during my time in Missouri, but the office of the property manager was closed both times. I followed up by phone and email, but got no response.

The apartment complex is adjacent to busy U.S. Highway 24, which is lined with businesses: a gas station, a sub shop, phone stores, a CVS. The police report makes no mention of any of the stores being contacted, so it is unknown if any security footage was available. The report does indicate detectives contacted three homes just behind the fence to Taylor's old apartment but residents had no information.

While I was in Kansas City in November, one of my trips to Stoneybrook was with Taylor. Standing outside her old building, she pointed out the terrace of her former third floor apartment. Right where we were standing, she told me, is where the police located the missing piece of doorjamb. As we were leaving, I noticed a trail that led into the stand of trees behind the apartment. We walked the trail about 10 feet through the trees where it opened onto a large, empty field of tall grass and weeds. Taylor told me she didn't even realize the trail was there. There is no mention of the field in the police report.

Also in the documents is a supplemental report filed by another officer, describing going to the hospital to follow up with Taylor and to get her to sign a medical release form that would allow the hospital to share information that might aid in the investigation. "Upon arrival, I contacted Taylor's ER nurse," the officer wrote. "The nurse advised that she had been unable to observe any injuries on Taylor, and that Taylor had changed her story with the hospital staff several times; advising that there had been first 3, then 4, then 5 attackers. I contacted Taylor, who advised that she had been struck by her attackers on her ribs, back, and neck. Taylor appeared nonchalant while describing her injuries and did not seem upset. The only injury I was able to observe at the time was a minor scratch on Taylor's side."

When Taylor saw this report, she lost it. She scrawled on her personal copy of the IPD report, "this never happened!" She has no recollection of a police officer contacting her at the hospital. She only remembers nurses, specifically her SANE nurse.

The SANE nurse's report reveals the extent of Taylor's injuries. The nurse photographed bruises and abrasions on her right breast, bruises on her left breast and nipple. Taylor reported that "one man kept pinching and pulling on my breast." The nurse noted scratches on Taylor's abdomen and side, and a bruise on her leg, as well as multiple lacerations and bruises around Taylor's vagina and anus, and an abrasion on her cervix. Vaginal bleeding was present. The nurse took 46 photos of Taylor's injuries, and the only officer mentioned in the nurse's report is the one who was first on the scene at Taylor's apartment.

I made numerous attempts to contact the IPD including going to the police station. The detective who interviewed Taylor did speak to me in the police department lobby but had no comment on the case. I also attempted to contact, by phone and email, the officer who filed the supplemental report at the hospital. IPD Major Paul Thurman, IPD's investigations divisions commander, responded to my requests for comment via memo that reads in part: "Your repeated inquiries into a specific sexual assault investigation have been acknowledged; however, victims of person crimes and the subsequent investigation are protected under applicable Missouri State Laws."

Taylor says she was in bed with her daughter at the Stoneybrook apartment complex when multiple men broke into her apartment and raped her.

"I kept thinking, How could I be a more perfect victim," Taylor said throughout my time with her. "I was sober, dressed in sweatpants, sleeping in my locked apartment on the third floor with my daughter, not on Tinder or OkCupid, not dating or married … and still wasn't believed."

When Taylor referred to a "perfect victim," she was referring to one of the most pervasive rape myths, long documented and studied inaccurate assumptions about who a rape victim should be. The "perfect victim" is so utterly without "flaws" that it would be impossible to blame her for what happened. She doesn't drink, she doesn't dress provocatively, she doesn't sleep around, she doesn't do anything that could possibly put her in harm's way. It's because this myth persists that the victim in the Brock Turner case had to explain that "alcohol was not the one who stripped me, fingered me, had my head dragging against the ground, with me almost fully naked. Having too much to drink was an amateur mistake that I admit to, but it is not criminal."

Taylor knows that the perfect victim doesn't exist and that a victim shouldn't have to be "perfect" in order to be believed. The point she was making is that even for those who do buy into rape myths, it would be hard to apply them to her case. She went for an exam, she reported immediately, she wasn't in a relationship so, she says, reporting the rape "couldn't be written off as some attempt to cover up an affair." She was a single mom, sleeping in her own bed with her toddler.

"My case was the kind that should have been easy to investigate and believe," she said.

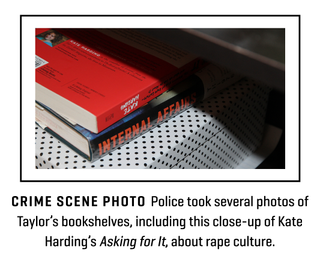

In her book, Asking for It: The Alarming Rise of Rape Culture and What We Can Do About It, Kate Harding lays out a list of other myths that plague victims of sexual assault: She asked for, it wasn't really rape, she lied, and, inexplicably, "he didn't mean to" or rape was some kind of miscommunication. Focusing on what a woman wore, whether she was drinking, or if she'd previously indicated that she wanted sex before saying no places the victim squarely in the frame as suspect and gives dispensation to the perpetrator.

And yet when Taylor received her police report and saw the crime scene photos, she immediately felt like she was being investigated. "It was like they were working for the defense," she said, "Or trying to diminish the severity of the attack based on my not being a virgin and being a sexual human."

Among the photos of the busted doorframe, opened kitchen cabinets, the bedroom, the bed, close-ups of sinks, and the door to the balcony are a picture of her vibrator that was between her mattress and box spring, a photo of some condoms in a wooden box, and a close-up of her ADD prescription medication.

Within the crime scene photos are also pictures of Taylor's bookshelf; one is a close-up of Kate Harding's book.

Taylor with her daughter, now 3, in Kansas City, Missouri, in December 2016.

Then around midnight on Oct. 10, 2016, Taylor's phone rang. It was the IPD detective who had interviewed her and had let her know her case was being closed. He had news. A man's DNA from a rape in nearby Johnson County, Kansas, had been run through CODIS — a tool used to track DNA evidence nationwide — and, as would later be revealed in court documents, there was a positive match to the sample obtained from Taylor's rape kit and it appeared to be the same suspect.

Hearing the news, Taylor went to her bathroom and threw up.

"Then there was a lot of anger it happened to someone else," Taylor said. "I was devastated about that."

The victim in the Johnson County case was a sheriff's deputy who was kidnapped and assaulted, according to the charges. The story got national media coverage and a reward was offered for any information in the deputy's case that led to an arrest.

On Oct. 11, 2016, Brady Newman-Caddell, 21, and William Luth, 24, were arrested and charged with the deputy's rape, to which they pleaded not guilty.

Then, on Friday, Dec. 23, 2016, as Taylor was preparing to spend the holidays with her daughter and father, Newman-Caddell, though already in a Johnson County jail cell, was charged with the rape of Taylor Hirth. According to the detective's probable cause report, which was made public when the charges came down, the accused lived in Taylor's old apartment building one floor below her. Looking back, Taylor told me, she remembers him holding the main building door for her a couple of times as she juggled bags of groceries and her daughter.

The detective erroneously listed the same apartment number for Taylor and Newman-Caddell, but when I emailed Jackson County chief trial attorney Michael J. Hunt, the lawyer prosecuting the case, about this report, he replied, "I am not allowed to comment publicly on pending cases."

Newman-Caddell was charged on four counts: rape, sodomy (anal and oral), and child endangerment. He has not yet entered a plea in the case and whether he will be convicted on any count remains to be seen, but Taylor told me she almost cried in relief when she saw the last charge. Not only did prosecutors believe that Taylor had been raped, they also believed they had enough evidence to indicate her daughter had been put in grave danger as well.

But Taylor's relief was fleeting. According to the probable cause report, dated Oct. 11, 2016, the defendant told the detective assigned to Taylor's case that his friend William Luth had raped Taylor and encouraged him to join in. Newman-Caddell told him he entered her "a ½ inch" but couldn't keep an erection. Luth, whose birthday is Feb. 8, the day before Taylor's rape, has not been charged in Taylor's case. Newman-Caddell also told the detective that no one else was involved, but Taylor remains confident there was at least one other assailant.

Luth's lawyer, David Bell of Wyrsch Hobbs & Mirakian, P.C., said he had "no comment at this time."

Taylor says the rape and the investigation have taken their toll. She casually mentioned to me that she bought Rogaine because her hair started falling out in clumps three months after the rape. Her weight has fluctuated. She tries to eat right and practice self-care, but she always feels stressed out waiting on something, whether it was her police report, a DNA match, a callback from the IPD or the prosecutor.

In the first days and weeks following a sexual assault, victims often experience acute stress disorder (ASD). Symptoms can range from loss of sleep and feelings of anxiety and stress to feeling physically and emotionally numb and being unable to recall certain details of the assault. ASD is much like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), only PTSD occurs over longer or delayed periods of time. Studies cited by the National Center for PTSD at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs found in the first weeks following a sexual assault, 94 percent of women reported symptoms of PTSD. After nine months, 30 percent reported the same pattern of symptoms.

Taylor told me she saw a therapist for about five months after the attack. Though she hasn't gotten an official diagnosis, Taylor said her therapist believed her symptoms—including the hair loss—are indicative of both ASD and subsequently PTSD.

When her case closed in August, Taylor started piecing her life back together. Or as she put it, "There wasn't anything to wait on anymore." And then came the detective's call and Newman-Caddell's arrest, and she was back to waiting: for the series of hearings to come, for Newman-Caddell's plea, for anyone else to be charged, maybe even for a trial.

Newman-Caddell won't appear in court for this case until the resolution of the Johnson County case. Michael McCulloch, the Johnson County public defender who is representing Newman-Caddell, had no comment on either case.

Taylor says the whole experience has placed her in a "strange place to be" when it comes to her work as a victim's advocate.

"How, having gone through what I went through and am still going through, can I still encourage women to report?"

Follow Marie Claire on Facebook for the latest celeb news, beauty tips, fascinating reads, livestream video, and more.

-

The Most Coveted Designer Belts Are Also the Most Unrecognizable

The Most Coveted Designer Belts Are Also the Most UnrecognizableBuck-up. There's a fierce appetite for this luxury IYKYK accessory.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Charli D'Amelio Says Kim Kardashian "Inspired" Her to Work on Prison Reform

Charli D'Amelio Says Kim Kardashian "Inspired" Her to Work on Prison ReformThe social media star has partnered with REFORM Alliance.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Henry Cavill and His Girlfriend Natalie Viscuso Are Expecting Their First Child

Henry Cavill and His Girlfriend Natalie Viscuso Are Expecting Their First ChildCongratulations are in order!

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Documentaries About Black History to Educate Yourself With

Documentaries About Black History to Educate Yourself WithTake your allyship a step further.

By Bianca Rodriguez Published

-

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We KnowNetflix owes us answers after that ending.

By Zoe Guy Last updated

-

'Firefly Lane' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Firefly Lane' Season 2: Everything We KnowIn the immortal words of Tully Hart, "Firefly Lane girls forever!"

By Andrea Park Published

-

31 Different Pride Flags and What Each Stands For

31 Different Pride Flags and What Each Stands ForInclusivity matters.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

'Bridgerton' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Bridgerton' Season 2: Everything We KnowThe viscount and his new love interest hit Netflix at the end of March.

By Andrea Park Published

-

'Bachelor In Paradise' 2021: Everything We Know

'Bachelor In Paradise' 2021: Everything We KnowIt's back, baby!

By Andrea Park Published

-

In 'We Are Not Like Them' Art Imitates Life—and (Hopefully) Vice Versa

In 'We Are Not Like Them' Art Imitates Life—and (Hopefully) Vice VersaRead an excerpt from the thought-provoking new book. Then, keep scrolling to discover how the authors, Jo Piazza and Christine Pride, navigated their own relationship while building a believable world for Riley and Jen—best friends, one Black, one white, dealing with the killing of an unarmed Black boy by a white police officer.

By Danielle McNally Published

-

Love Has Lost

Love Has LostQuasi-religious group Love Has Won claimed to offer wellness advice and self-care products, but what was actually being dished out by their late leader Amy Carlson Stroud—self-professed “Mother God”—was much darker. How our current conspiritualist culture is to blame.

By Virginia Pelley Published