I Was One Of The Top Doctors In My Field. I Was Also An Opioid Addict.

Opioids have become a full-blown national crisis of epidemic proportions, killing 130 people each day. Drug overdose is now the number-one cause of death for Americans under 50. One doctor at the top of her game—who knew the risks better than anyone—almost became another statistic.

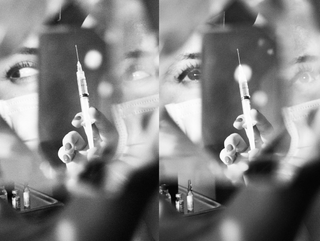

Alison ran around her palatial six-bedroom house in Georgia on a crisp January night in 2016, preparing to depart the next day for a family ski trip in Colorado. She washed dishes, tidied counters, put in several loads of laundry, and crossed items off her packing list. Whenever she found a moment alone—every 45 minutes or so—she retrieved the syringe containing sufentanil she’d tucked inside the Ugg boots she wore around her house, pulled a makeshift tourniquet out of her hooded sweatshirt, found a usable vein, and plunged the needle into her arm, delivering one tenth of a milliliter of the most powerful opioid available for use in humans.

That night, as Alison hustled her house into order, she shot up in her 13-year-old daughter’s closet (she once used her ballet-shoe laces as a tourniquet), her oldest son’s bathroom (he was away at college), the kitchen pantry (she sometimes kept vials inside boxes of dry pasta), the laundry room (her favorite place to use), the bathroom (her least favorite), and the stairway leading up to the second floor, where she could gauge if family members were getting close.

By the end of the night, she had polished off two milliliters, an amount that could kill an average-size adult if given in a single dose. Sufentanil is an opioid painkiller five to seven times more potent than fentanyl—another powerful opioid—at the time of peak effect and 4,521 times more powerful than morphine, but Alison wasn’t intimidated. As an anesthesiologist, she’d spent her entire professional life delivering such substances to patients during surgery.

What Alison didn’t know then was that in just over two months, her whole world would come crashing down. She had no idea that three nurses would grow wise to the ways she was stealing drugs from the hospital. Or that she’d spend 90 days at an in-treatment center, followed by a five-year monitoring program for physicians. All she was thinking about that night was that her drugs of choice, sufentanil and fentanyl, made her happy at a time when her work demands were overwhelming and her second marriage was falling apart. “It was immediate; everything just chilled out. For me, it felt like when you have a really good glass of wine and you’re like, ‘Ahhh,’ ” says Alison, now 46. “During that time, that was the only thing I looked forward to. That was really the only thing that was good in a day of life for me.”

Before she started abusing opioids six months earlier, Alison had never used a drug recreationally other than a puff of marijuana during high school. (She didn’t like it.) She enjoyed a glass of red wine with dinner once or twice a month but hadn’t ever thought of using the substances she injected into patients all day, every day. “I’d been in anesthesia for 18 years, and it never even tempted me,” she says. “I never wondered what it felt like. It did not enter my mind.”

Alison was raised in a small town in Tennessee, the third youngest of seven children born to strict, conservative Christian parents. Her father is a physicist who liked to pose math questions at the dinner table (“In a group of 27 kids, there are 13 more girls than boys. How many girls and boys are there? Go!”), and her mother is a stay-at-home mom. For vacation, “we didn’t go to the beach or Disney World; we went to a place with a telescope or a planetarium,” says Alison, recalling one trip in which they piled in a station wagon and drove to South Dakota to watch an eclipse.

Today, three siblings are physicians, one worked for the CIA, and another chaired a university department. Alison likes to joke that she’s the underachiever in the family, and though she deserves no such title, the lifelong pressure she felt to outperform her siblings took a toll. “I was raised in a family where the lowest thing that was allowed was perfection,” she says. “I felt like I needed to do more, always. That was a big thing that came up in treatment—that my ‘good enough’ wasn’t good enough.” She had an eating disorder as a young teen and remembers dropping 30 pounds from her petite frame one summer by consuming only iceberg lettuce and fat-free French dressing. She says she felt like a failure because a younger sister weighed 15 pounds less.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

One of Alison’s older brothers taught her square roots when she was two years old. (“It was like his little dog and pony trick to show me off to his friends,” says Alison, laughing.) She took up the violin at age four and started piano lessons when she was six. She skipped first and seventh grades and completed high school in three years, graduating days after she turned 16. She finished college in three years too and enrolled in medical school in California at 19. A wunderkind, yes, but she wonders now about the damage racing through her youth caused. “Perfectionism is horrible,” Alison says. “I know that I didn’t develop good coping mechanisms. Some of my treatment team thinks I got stunted.”

Medical school was the first time Alison had to study in her life. She chose to specialize in anesthesia because of how tangible it was. “I liked how when someone’s blood pressure is high, you give them medicine and it goes down,” she says. “That immediate gratification.” She married a man she met while she was in medical school when she was 22 and had her first son one month before graduation. (Her second son was born during her residency.)

Three years of her medical schooling were paid for by the Navy (“With my dad being a teacher and me being one of seven kids, there was no money,” she explains), so after finishing her residency, she paid the military back with three years of service, during which she was stationed at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. True to form, Alison was not just any anesthesiologist in the Navy, she was the one asked to do the anesthesia for a president (“A huge honor,” she says) and a high-ranking senator. (She was called in from maternity leave after giving birth to her daughter at the surgeon’s request.)

Alison left the Navy in 2003 and moved to Georgia, about an hour from where she grew up. She and her husband wanted to raise their kids in the South, and she was eager for a slower pace. The years of schooling and success with three young children had been hard on her marriage. “I fell in love with my kids immediately, and I let the marriage slip,” Alison explains. “I put my kids before my husband.”

For years, she bounced between area hospitals, taking a position at whichever had the best team, reputation, and equipment at the time. In the spring of 2007, she began an affair with a charismatic nurse. She originally wanted to set him up with one of her sisters, but one late night while they were on call together, he said, “I’m not interested in your sister.” By June, her husband had found out after seeing the nurse’s number on the caller ID. When he asked Alison about it, she confessed; they divorced after 11 years of marriage.

She continued to date the nurse on and off in the years after the affair. Their relationship was fiery and unstable, in the way that intensely passionate but ultimately destructive relationships can be. Alison knew he wasn’t good for her, but she was hooked. “Looking back on it, I’m sure on some level that was addiction too,” she says. “He was something super bad for me who I was with despite bad consequences.” They rekindled their romance a final time in 2011 and married just before Christmas the following year.

To outsiders, Alison’s life looked rosy. The newlyweds lived in a dream house they had built in the lush foothills of the Appalachian Mountains and took Alison’s kids on family trips to beaches in Florida and ski slopes in Idaho and Wyoming. In 2012, Alison accepted a job as the medical director of the anesthesiology department at one of the hospitals where she’d worked and quickly became the most-requested anesthesiologist by patients and surgeons alike. “Her quality was absolutely phenomenal,” says Lindsay Dembowski, her boss at the time. Other doctors would complain, “‘It’s not fair, she’s getting all the good cases,’” Dembowski says. “It was because she was so good.”

Behind the scenes was a different reality. On the business side, anesthesiology was run by an outside management group that Alison says cut corners and costs to the point where the department was chronically understaffed. “It was a horrible environment,” she says. Still, she ran herself ragged trying to be the best, as always. “I can’t shut it off,” Alison says. “I can’t go home and say, ‘We did a really good job today. I’ll do the rest tomorrow.’ I could never do enough. I was trying to fix things that were impossible to fix.”

The workload wasn’t good for her new marriage either. Her husband was pulling away, they were fighting constantly, and she had learned he was using opioids recreationally. They were in the car one day, talking about fentanyl, and Alison remembers saying something like “You can’t even use it once or you’re addicted.” Her husband replied, “Yeah, that’s not true,” and told her he used it sometimes. “He was the first face I ever put to drug use, and I worshipped the ground he walked on at that point, so I thought, This person is not a loser, he knows what he’s doing, he’s good at what he does,” she says.

Soon, her husband was asking her to get some from the hospital for him. “I didn’t have to ask anyone to write me a prescription; I had absolute access,” Alison says. She resisted at first but gave in a few times, bringing home fentanyl left over in a syringe at the end of surgery. (The needle is uncontaminated, as it is injected into an intravenous line rather than directly into a person.) There’s an official protocol for the disposal of unused drugs at the end of an operation. Waste procedures vary from hospital to hospital, but generally doctors are supposed to have a nurse or assistant physically watch them drain the syringe into a sink or trash can. But in a fast-paced hospital environment, doctors will often ask someone to watch who isn’t really paying attention. “It’s pretty easy,” Alison says. “No one stands there and looks.” In hospitals where the person serving as a witness has to enter a code, doctors commonly know nurses’ codes and enter them even if no witness is present. (To prevent this, some hospitals now require both the physician and the witness to identify themselves using a thumbprint scanner.)

On Father’s Day in 2015, Alison was home alone; her husband was with his dad, and her kids were with their dad. She was putting away laundry in her husband’s closet when she found pockets and shoes full of empty fentanyl vials—more than she’d ever stolen for him. She confronted him when he got home, but “he tried to downplay it, and I just made up my mind that I would never give it to him again,” she says.

Alison already had a vial of fentanyl she had swiped for her husband sitting in a drawer at home; she’d slipped it into her pocket when a surgery she’d already prepped for was canceled a few weeks earlier. “For whatever reason, I hadn’t given it to him yet,” she says, “and when I decided I wasn’t ever going to again, instead of squirting it out, I just let it sit there.” There were “more bad days than good” those weeks, and the vial was still sitting there six weeks later, after she and her husband had another big blowup. “I was like, You know what? He says fentanyl is what makes life better for him when the world’s falling in. I’m gonna go try,” Alison says. She went into her bathroom and injected a “tiny, tiny, tiny” dose in a vein on the back of her right hand. “All of a sudden, everything was OK,” she says. “I would say it’s like immediately going from zero to the happiest buzz you’ve ever had.”

She shot up because she was “careless and reckless with a fuck-it mentality” at that point. “My justification was that I was a victim. I was a martyr. Work was terrible to me, my marriage was a sham, so I deserved it,” she says. “In an instant, my whole idea about myself, my moral code—I let it go.”

Maybe a week or so later, she used again. She came home and made dinner, and at around 8:30 p.m. she went into her laundry closet. “I was like, ‘Ohhh, OK,’ and finished whatever I needed to do, watched TV in peace, and was able to sleep. That was a big thing—because I definitely had been having trouble sleeping.” Within a few months, she went from using once to using every so often to using as soon as she walked in the door from work. Sometimes even that wasn’t soon enough: She would shoot up in her car in the hospital parking lot or after working out at her gym before driving home. She’s mortified to admit that at least once she picked up her daughter from dance practice and drove her home while high.

Soon, she was injecting fentanyl first thing on a Sunday morning and, because the effect wears off after one to two hours, reupping as many times as it took to make it to bedtime. “For me, that’s what I liked; it was my hobby, my favorite thing to do,” she says. Her dosage and the number of times she used in a day increased rapidly as well. “I remember a couple of times thinking, Let’s try a little more this time, and it was way too much,” she says. “One Saturday night we were watching a movie and I could not keep my eyes open. I’m sure my family just thought I was super tired.” Alison also began using the more potent sufentanil when she could get it. “When you’re getting the needle out, you’re almost salivating,” she says. “It’s like you’re just about to eat. You’re starving. It means relief is about to happen; you’re almost there. It’s very primal.”

That’s not to say using was always a positive experience. She took some fentanyl to a friend’s Halloween party she attended with her husband (she hid it up her sleeve) and locked herself in the bathroom after they arrived. “I was very, very irritated with myself,” Alison says. “I remember being like, All the people out there are socializing, and this is what you’re doing?” She and her husband never used together; when he found out about her fentanyl abuse six weeks in, he was furious and began trying to thwart her efforts by checking her bag before she left the hospital when their shifts overlapped. Alison once put a vial in her shoe and tried to limp out without him noticing, but he caught her and threw it in the trash. On Thanksgiving morning, Alison discovered her husband had thrown out a whole vial of fentanyl she had hidden in a duffel at the back of her closet. Seething, she locked herself in her daughter’s room. (She was spending the holiday at her dad’s.) Alison called her parents, who were expecting her for dinner, to tell them she wasn’t going to make it. (She lied and said work had called her in.) “That made me feel pretty lame about myself,” she says. Another night, Alison mistook ketamine, a heavy sedative, for fentanyl and was unable to talk or move for hours. “That was very scary. I was lying on the bathroom floor like, Oh, shit, what have I done?” Alison says. “I remember cussing to myself, You’re an idiot and this is disgusting. This is the level you’ve now dropped to! And yet, that wasn’t the last time I used.”

There were many days when Alison woke up thinking, I’m not going to use. I have to stop. But then she would walk into work and “it was almost like my brain was someone else’s—it was a switch, like a zombie in a movie—like, Of course you’re going to get some, you need it,” she says.

Alison swears she never shot up before work, but when she was at the hospital, looking for opportunities to steal leftover drugs preoccupied her mind. “I would make a plan,” she says. “In the morning, I’d already be thinking, Will I be able to use today? When’s there going to be time? Will I be able to get some? What cases does it look like I’ll be able to steal from? What’s the best chance?” As director of the department, she could pop into whatever surgeries she wanted, so she would often come by when an operation was finishing up to see if she could snag any unused drugs. Other times, she would check out more opioids than a procedure required, ensuring there would be some remaining, or add sufentanil to the cocktail of drugs given to a patient even when it wasn’t required. “Sometimes the only reason I gave sufentanil was so I could get it to me,” Alison says. “It’s not harmful, but it wasn’t necessary.” She also swapped syringes filled with saline for those filled with drugs to trick the person watching her waste, or she marked an opioid on a patient’s chart that he or she had never been given. Alison never resorted to pouring the liquid from the sharps bucket, where syringes are disposed, but she’s heard of others who have (despite the risk that the mixture of unknown substances at the bottom of the bucket could be a lethal combination). She also knows of physicians who steal pills from prescription bottles patients bring with them to appointments.

When Alison started regularly using after hours, she never paused to reflect on how the drugs could impact the work she did from home every night. “I had to make the schedule, talk to surgeons, answer questions,” she says. “I was cognizant enough, but I wonder if any of them would say, ‘Well, yeah, she acted a little more spacey.’ I don’t know if someone felt that and just didn’t tell me.”

Some of her coworkers were indeed taking note. In March 2016, about eight months after Alison started using, her boss got a call from a nurse anesthetist who said she and two others—Alison’s three best friends at the hospital—had been conducting an investigation after noticing some missing narcotics. “I remember thinking, Who in the world?” Dembowski says. When she sat down with the nurse anesthetist the next morning to hear the evidence, she was shocked. “I thought, There is absolutely no way. Of all the people—Alison was my best doctor—she would have been the last one on my list of suspects.”

The nurse anesthetist had been tipped off back in January when she noticed Alison had marked on a chart that she’d given sufentanil to a patient not long after the nurse had given fentanyl. “The nurse anesthetist was like, ‘Why would she give sufentanil when I was giving fentanyl?’ The patient must have been in a lot of pain,” Dembowski says. (The nurses declined to be interviewed.) But of course the patient wasn’t in that much pain and had never been given the sufentanil. Alison had pocketed it. The nurse had documented a number of similar incidents. “There was enough evidence,” Dembowski says. “There was no way she could deny it.”

Alison remembers one Friday when she’s sure one of the three nurse anesthetists who turned her in saw a syringe in her pocket as she was leaving work. “We were talking and I noticed her staring at it,” she says. “She didn’t say anything; she was just looking. Of course I had a guilty conscience, but then I was like, No, no, she’s not going to think that.”

The following Tuesday, Alison got a text from her boss saying, “Hey, are you around? We need to meet with you.” Dembowski and her boss sat Alison down and told her what they knew. At first, she got defensive and denied it. “Nope. Nope. Didn’t do it,” Dembowski remembers her saying. But when they told Alison she was going to have to take a drug test, she broke down. “She was like, ‘What do we do from here? I did it,’” Dembowski says. Alison knew she’d never return to work at that hospital (she later resigned), but she was told she could keep her medical license if she immediately enrolled in treatment. “My heart sank,” Alison says. “I felt like my life was over.”

The risk of suicide is high when addicts are caught, Dembowski says, so she couldn’t let Alison out of her sight. They escorted her from the building, Dembowski drove her home to pack a bag, and they set off on a two-hour drive to a treatment center in Atlanta. Alison called her husband and her children from the road. (Once she arrived at treatment, she would be barred from talking to them and everyone else on the outside for 30 days.) “I’m sure she probably hated me,” says Dembowski, remembering how Alison worried about how she would pay her bills, what would happen to her kids, and whether she would be home in time for Easter and Mother’s Day. “In her mind, I’d just ruined her whole life.”

She took Alison to Talbott Recovery, an in-treatment center started in 1989 by George Talbott, an internist who struggled with alcohol abuse and pioneered the first treatment program specifically for doctors like himself. “It’s very easy, with the stigma addicts face, to say, ‘You’re an addict, you’ll always be an addict, you’re good for nothing,’” says Navjyot Singh Bedi, Talbott Recovery’s medical director. “Dr. Talbott decided he must find a way to not only get physicians the help they need but also advocate for them returning to practice medicine, because addiction does not take away their ability to care for other human beings. They don’t lose their medical knowledge or skills.”

Alison spent the required 90 days at Talbott, far longer than what’s offered at most in-treatment programs, which typically last 30 days at most (a length, Bedi says, that was “manufactured by insurance companies,” not proven by science). The treatment cost was about $45,000; Alison paid nearly $30,000 out of pocket. The rest was covered by insurance.

Opioids are the second most frequently abused substance among physicians, after alcohol, so there were other fentanyl users in Alison’s group. Though Talbott also offers programs for the general public, the doctors interact only with one another because, well, their egos are too large. “You put a physician in a regular treatment center and all of the oxygen in the room gets taken over by this narcissist who thinks they know everything and doesn’t ever discuss their own vulnerabilities or sadness,” says Bedi, who notes doctors don’t use their honorific titles at treatment. “We want them to leave their credentials at the door and focus on the disease that’s coming to kill them.”

The program is lengthy, which is particularly good for doctors because “they are really, really smart, and the smarter you are, the harder it is to get the basics of recovery because you can kind of outthink your feelings,” says Debbie Ray, Alison’s case manager at Talbott. “We have to get them to put themselves out there and be vulnerable, which is not an easy thing for a physician to do. I always tell my patients, ‘You’re going to see a sadistic-looking smile on my face when you’re in the middle of telling the hardest story of your life.’ Because when I hear them do that, that’s where the work begins.” In treatment, Alison had to “learn I’m a regular person, not superhuman,” she says. “This whole experience has brought me into the human race.”

At Talbott, participants live, eat, and do everything with at least one other person. “We couldn’t go anywhere by ourselves, which as an adult is difficult,” Alison says. “But I know I wouldn’t have gotten better otherwise. I was sick, and it was absolutely what I needed.” When they grocery shopped, they did it as a group—no splitting up to grab tortillas while another person gets fruit. (One time, at CVS, a member of her group somehow snuck away to drink Listerine, which contains alcohol, Alison remembers.)

They woke around 7 a.m. Talbott staffers would inspect the group apartments, looking for cleanliness and contraband. “There were all these rules, like the coffee maker had to be unplugged,” Alison says. “It reminded me of being in the military.” They would arrive at the treatment center by 8 a.m.; when they walked in the door, they would learn if they had to take a randomized drug test. If not, they went to a morning meditation session, followed by hours of lectures, group discussions, and meetings where they worked on the 12 steps common in many treatment programs. Like Step 4, which requires addicts to make a “searching and fearless” moral inventory. Before that, “I hadn’t let myself acknowledge that I could be hurting other people with my drug use,” Alison says. “I really thought I was only hurting myself.”

After in-treatment ended, Alison signed a five-year monitoring agreement with her state’s physician health program (PHP). Doctors in recovery who are enrolled in PHPs can continue to practice in the vast majority of situations as long as they remain healthy and meet requirements like checking in every day to see if they have to take a drug test and attending support-group meetings and other therapy. If they fail to comply or prove to be a risk to public safety, the PHP may need to report them to the medical board and they could lose their license.

Every Tuesday, Alison drives to Atlanta to attend a small group meeting with nine other physicians, followed by a large meeting with around 80 other doctors, physician assistants, and respiratory therapists. She’s also required to attend self-help group meetings, like Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous. She had to go to a meeting every day in the beginning, but that tapers off over time; three years in, she goes three or four times a week.

All but four states—California, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wisconsin—have independent PHP programs. The first was founded in New Jersey in 1982; Georgia’s is the newest and was started in 2012. Similar long-term aftercare monitoring programs exist for impaired pilots, who, like physicians, put the public at risk if they relapse. “The consequences of treatment failure are high, so we might even overtreat them a bit to make sure we reduce the likelihood of relapse,” Bedi says.

The PHP model has shown remarkable results. The first national study of state PHPs, which was published in the Journal of Substance Abuse in 2009, found that of 904 physicians enrolled in 16 state PHP programs, 78 percent had no positive test for either drugs or alcohol during the five years of intensive monitoring, and 72 percent continued to practice medicine. “Almost all my people get better,” says Dr. Paul Earley, medical director of Georgia’s PHP and president-elect of the American Society of Addiction Medicine. “PHPs have a success rate which is unparalleled, and the reason physicians do so well is they get a ton of treatment. Everyone should get that kind of care.” Smaller studies have shown similar results. “Addicted physicians treated within the PHP framework have the highest long-term recovery rates recorded in the treatment outcome literature: between 70 percent and 96 percent,” the authors of the 2009 national study wrote.

Such outcomes raise a question: Why do addicts have to have a medical or pilot’s license to receive such high-quality care? There’s no official estimate for how often treatment works for the general public nationwide, but a frequently quoted figure is that just 30 percent of people abstain from using for a year after treatment. (And that’s only among those who complete a program; anywhere from 20 to 60 percent of addicts drop out, according to a 2013 study published in Clinical Psychology Review.)

With 130 people dying of opioid overdoses in the U.S. every day—nearly 50,000 people died in 2017 alone—wouldn’t we want as many people as possible to have access to the most effective treatment? Why that isn’t the case is simple: Insurance won’t pay for more-expensive long-term care unless a person has already flunked out of less extensive and costly options, Bedi says.

Even worse is that 80 percent of opioid addicts are not getting any treatment at all, according to a research letter published in JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association in 2015. Of the treatments available to the general public, few mirror the PHP model. There are two standouts that do. One is Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (HOPE) program, which aims to reduce alcohol and drug use and recidivism among high-risk felony probationers. A one-year independent randomized control study of HOPE conducted in 2009 found participants were 72 percent less likely to use drugs, 55 percent less likely to be arrested for a new crime, and 53 percent less likely to have their probation revoked. Similarly, a study of 4,009 people enrolled in South Dakota’s 24/7 Sobriety program, designed to reduce the state’s unusually high rate of drunk driving, found 99.4 percent of participants passed the twice-daily alcohol tests they were given each day.

The reason doctors get such high-quality care is that the medical profession treats addiction not as a character defect but like the serious condition it is. “Addiction is a chronic brain disease that cannot be treated with short-term measures,” Earley says. “PHPs look at addiction as a chronic disease—more like diabetes than appendicitis. And like diabetes, you have to educate patients on how to care for themselves.” Such care can be expensive: Georgia’s PHP costs $430 per month for five years, for a total of $25,800, plus an additional $120 per month for drug tests, all of which the physicians pay out of pocket—but it’s cheaper than dealing with the health conditions or imprisonment that can come with sustained relapse. (For PHPs in other states where costs are offset by physician licensure fees, hospitals, and malpractice carriers, rates may be as low as $150 per month; Georgia’s state legislature mandates the costs of the PHP be covered by participants.)

The stigma on addicts in society as a whole has started to decrease amid the opioid crisis, thanks in part to the fact that people of privilege like Alison got hooked, cluing the public in to what researchers have always known to be true: Anyone can become addicted. “A silver lining to the opioid epidemic is it has brought the disease into the conversation,” Bedi says. “People are beginning to see these are our friends, our coworkers, our relatives. We cannot discriminate against them, we cannot deny them access to treatment—this is a lethal condition.” It’s an overdue change from the crack epidemic in the 1980s, which notoriously led to mass incarceration as African Americans were sent to prison rather than treatment programs. “People are realizing that you can’t just wish away addiction by saying, ‘We’re not going to treat it,’” Bedi adds. “You will have this enormous burden explode in your face if you ignore the disease.”

There has been a lot of progress, but we’re not there yet. There’s still so much disgrace surrounding physicians in recovery that Alison worried she’d never work again. “It’s a small town; everyone knows,” she says. “I was the biggest news in town.” A majority of anesthesiologists do not return to that specialty after struggling with addiction because the easy access makes the temptation too real. “Most would say, ‘Well, this tiger might not bite me, but I’m not going to hang around and pet it all day long,’” Earley says.

But Alison is not most people. Because she had no prior history of drug abuse, had practiced anesthesia for nearly two decades without incident, is doing well in treatment, and gets a monthly injection of naltrexone, an anti-addiction drug that blocks opioid cravings, she was allowed to return to the operating room. She landed a job in the anesthesiology department at a hospital about 30 minutes away from where she lives. Fentanyl is used in almost every surgery, so she has to handle it constantly. “They say it’s the equivalent of an alcoholic as a bartender,” Alison says. She thought she might think, You’re the thing that ruined my life when she touched a vial again for the first time, but instead she felt neutral. The drug had lost its power.

Upon her hiring, she offered to take additional precautionary measures—like returning all leftover drugs to the pharmacy or having someone regularly review her charts—but so far, her new workplace hasn’t required her to do anything extraordinary. “I’m not going to relapse. That’s what I tell myself every day,” Alison says. “I will do whatever it takes to stay sober, even if it means quitting anesthesia.”

Alison says she hasn’t been tempted, but she’s always careful to add a yet to the end of that sentence. “I don’t want to get complacent,” she says. Sometimes when she has a lot of leftovers at the end of a surgery, she thinks, There you go, you could have all of that right now, but then she goes to the garbage can and squirts it out. “I haven’t had any physical cravings at all,” she says, noting that the only time it even crossed her mind was when she and her second husband divorced 10 months into her treatment. “It was one of the really bad days. I was home by myself, and I was like, Man, I miss when I used to use. It wasn’t a craving; I just remembered how it fixed that feeling, temporarily at least.”

Eventually, Alison was able to reconcile with most people in her life, except for the three nurse anesthetists, with whom she’s had only brief interactions and text exchanges. Her old boss, Dembowski, says she gets a text from Alison every few months saying, “Thank you for saving my life.” Her children forgave her, and they’re closer than ever. They meet for Orange Theory workouts, cheer for her now-15-year-old daughter at volleyball games, and gobble down pizza at the best spot in town.

She thinks recovery has made her a better, more empathetic doctor. She doesn’t tell patients about her history. (It’s a liability issue.) “I want to say, ‘Look, I’m in recovery myself,’” she says. “‘I’m often the smartest person in the room, and I made the dumbest decisions. There is no judgment.’” Instead she says something like “I’m very familiar with recovery.” She’s also been approached by friends seeking help for family members struggling with opioid addiction. “To see the pain I caused my family used to help someone else’s, it’s amazing,” Alison says. “That something good came out of something horrible that’s something, whatever it is, greater than me. And it’s pretty cool.”

Alison hopes sharing what she’s been through will help to reduce shame. “Addiction is a nondiscriminating disease. It doesn’t care what color you are, what age, what sex, what religion, your socioeconomic status; it is an equal-opportunity offender,” she says. “Maybe 20 years from now my story will help to change the stigma and people won’t automatically think their doctor is a horrible person just because they’re in recovery.” To that end, she wanted to use her full real name in this story, but her bosses wouldn’t allow it, which is why we’ve used her middle name here. They were afraid of what her patients would think if they Googled her.

Photographs by Allie Holloway.

This story originally appeared in the March 2019 issue of Marie Claire.

Kayla Webley Adler is the Deputy Editor of ELLE magazine. She edits cover stories, profiles, and narrative features on politics, culture, crime, and social trends. Previously, she worked as the Features Director at Marie Claire magazine and as a Staff Writer at TIME magazine.

-

A Healthy Scalp Is the Secret to the Best Hair of Your Life

A Healthy Scalp Is the Secret to the Best Hair of Your LifeSponsor Content Created With KilgourMD

By Emma Walsh Published

-

Jennifer Lopez Puts Her Navy Outfit Into Overdrive With a Matching Birkin

Jennifer Lopez Puts Her Navy Outfit Into Overdrive With a Matching BirkinIs it really a J.Lo outfit without this particular purse?

By India Roby Published

-

Will Prince Archie and Princess Lilibet Appear in Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s Two New Netflix Series?

Will Prince Archie and Princess Lilibet Appear in Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s Two New Netflix Series?Filming for both shows—about polo and cookery—began this month.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Dear Survivor: You Are Enough by Merely Existing

Dear Survivor: You Are Enough by Merely ExistingIn honor of Sexual Assault Awareness Month, Rise founder Amanda Nguyen writes a love letter to her younger self.

By Amanda Nguyen Published

-

Dear Survivor: Tarana Burke Wants You to Hold On to Hope

Dear Survivor: Tarana Burke Wants You to Hold On to Hope"We need to heal—and in order to heal, we must have the capacity to hope that that work to end sexual violence IS possible."

By Tarana Burke Published

-

My Tarot Card Dependency Controlled My Life

My Tarot Card Dependency Controlled My LifeFor years, Remy Ramirez didn't make a move without consulting her tarot deck. Through meditation and therapy, she was finally able to break her addiction...but only after being held captive to the cosmos.

By Remy Ramirez Published

-

Friendship, Infertility & Moving Forward

Friendship, Infertility & Moving ForwardThere’s no rulebook for navigating your pregnancy while your best friend struggles to conceive. I learned that the hard way.

By Victoria Lamson Published

-

Millions of Americans Have My “Invisible Disability.” You’ve Probably Never Heard of It.

Millions of Americans Have My “Invisible Disability.” You’ve Probably Never Heard of It.Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) can make daily life a struggle. So why isn’t it better known?

By Jenny Hollander Last updated

-

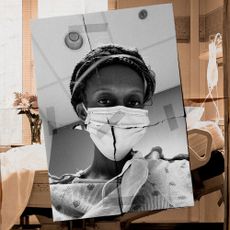

When Your Breast Cancer Journey Takes an Unexpected Turn

When Your Breast Cancer Journey Takes an Unexpected TurnAfter an annual mammogram in June revealed suspicious calcifications, breast cancer survivor Kai McGee underwent a partial mastectomy. Now, she's grappling with the outcome of that surgery.

By Kai McGee Published

-

The Coldness of Enduring Breast Cancer in a Covid-19 World

The Coldness of Enduring Breast Cancer in a Covid-19 WorldIn June, breast cancer survivor Kai McGee went to the hospital for her annual mammogram and ultrasound. Now she has to decide the next steps in her treatment journey, an already-stressful process made worse by the isolation of Covid-19.

By Kai McGee Published

-

A Devastating Choice: Deciding Between a Lumpectomy or Mastectomy

A Devastating Choice: Deciding Between a Lumpectomy or MastectomyWhen Kai McGee was diagnosed with stage II breast cancer six years ago, she was forced to choose between saving her breasts and risking a possible cancer occurrence in her healthy breast in the future. Now, she's grappling with the after-effects of that choice during a pandemic and a summer of racial reckoning.

By Kai McGee Published