A flash-bang detonated, causing the crowd of 1,500 to crouch and cover their ears. Protestors buckled their bicycle helmets, tightened their goggles, and adjusted their ear plugs. Then a cloud of gray smoke bloomed from the center of the group.

Tear gas.

People wearing respirators used leaf blowers to disperse the chemical agent volleyed at protestors by the federal agents guarding Portland, Oregon’s Hatfield Federal Courthouse on July 24. “Stay calm,” someone shouted. “Walk, don’t run.” Those of us on the periphery of the protest shuffled farther away.

I was several blocks from the center of the declared riot and didn’t see any smoke around me, so I was shocked when my eyes began to burn. I heard people retching nearby. A stranger guided me to a pair of medics. They poured water over my face and dripped saline into my eyes.

One warned me that the water he doused me in wouldn’t get rid of the tear gas residue on my clothes, skin, or hair. “Shower like this,” he said, sticking his face forward and butt back. “You don’t want this stuff burning down there.” I caught his meaning.

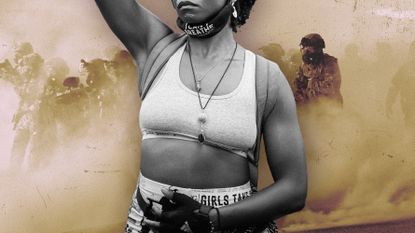

Protestors in Portland wear gas masks to protect themselves from chemical crowd control measures.

This particular night wasn’t much different from the months of clashes between law enforcement and activists in Portland. A University of Portland study shows that federal agents used tear gas as early as on July 3, sometimes as often as 33 times in a single night, until they transitioned defense of the courthouse to state troopers on July 30. Officers with the Portland Police also repeatedly used, and continue to use, the chemical agent against protestors.

Oregon’s largest city is only one of many places across the country and the world where crowds have demanded justice since the death of George Floyd on May 25. Protestors in at least 100 cities in the U.S., from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to Wilmington, North Carolina, were hit with some form of tear gas this summer. Mass demonstrations—and the “less lethal” methods of dispersing them—don’t show signs of stopping.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Now, protestors and some medical experts are questioning if tear gas can do more than cause “burning down there.” People with a uterus have taken to social media to compare notes on unusual changes to their menstrual cycle since being exposed to tear gas—periods coming extra early or late; debilitating cramps; and bleeding heavy enough to require an adult diaper.

“I’ve had multiple periods in one cycle,” says Danialle James, an activist in Portland who has protested nearly every night since George Floyd was killed and who jointly filed a lawsuit against a smorgasbord of federal officials and agencies that have used violence to subdue protestors. She says she has been exposed to tear gas “too many times to count,” including every day in a two- to three-week stretch. “Whether it was close to my time [of the month] or not, I also experienced severe menstrual cramps.”

We’re dealing with something that could kill us. But I’m Black. It’s my duty to fight for my freedom.

Many other protestors report similar symptoms—in addition to the burning eyes, cough, and breathing difficulties that regularly result from exposure to chemical agents. James says that every night, she and other women compare symptoms they identify as side effects of tear gas. Some symptoms vary—one woman’s eyes are constantly red, one woman is dealing with hemorrhoids, another’s hair has fallen out—but “we have the same uterus-type things going on,” confirms another Portland activist, Demetria Hester.

Still, Hester and James, along with hundreds—even thousands—of others have continued to show up nightly with every expectation of being exposed to tear gas yet again. “We’re dealing with something that could kill us,” James continues. “But I’m Black. It’s my duty to fight for my freedom. My duty to fight for my civil rights.”

Irritating Agents

“Tear gas” is a catch-all term used to describe crowd-control tools that, when dispersed, cause eye pain and tearing, coughing, disorientation, and other quick-acting but typically short-lived symptoms. (They’re also called “irritating agents,” a euphemism that implies they are as mildly annoying as pop-up ads.) A study authored by medical officers in Britain wrote that people exposed to tear gas are “highly motivated to escape from the smoke.”

2-Chlorobenzylidenemalononitrile, a real tongue twister of a chemical commonly called CS, is often used by law enforcement in the U.S. It’s actually a powder, not a gas, that is dispersed into the air when the cannister carrying it explodes.

If this sounds violent, that’s because it is. The tools are prohibited under international protocols, and the reason why law enforcement still uses them is complicated: The Geneva Protocol, signed in 1925, banned weaponized gases in war in response to the devastating chemicals that killed roughly 100,000 soldiers in World War I. The United States ratified the articles under the UN’s 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention in 1997, which banned the production, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons in warfare—but included an exception for “law enforcement, including domestic riot control purposes.” More recently, President Trump signed a bill banning the export of crowd control supplies, including tear gas, to Hong Kong, where there was a crack down on widespread protests in 2019.

Police bureaus in Portland, New Orleans, Oakland, Philadelphia, and other cities have defended their department’s use of tear gas. "CS gas is uncomfortable, but effective at dispersing crowds,” Portland Police Chief Chuck Lovell said at a press conference on July 1. “We would rather not use it. We'd rather have those in the area follow the law and not engage in dangerous behavior. We provide plenty of warning and everyone there had the opportunity to leave to avoid the use of force.” Police leaders say that using tear gas causes less harm than other crowd control measures, such as the brute force of batons and riot shields.

A protester throws back a tear gas grenade after federal officers tried to disperse a crowd in Portland.

The prevailing wisdom around tear gas suggests that it causes pain, but no lasting harm. The limited study of CS, primarily in military training exercises, has several limitations, though. For the most part, the subjects in these studies are young, healthy males—not exactly a cross-section of the people who are taking to the streets to decry systemic racism. Plus, the severity of the effects of CS, specifically, can vary based on temperature, humidity, and wind patterns. What’s more, these studies seldom investigate repeated or prolonged exposure or widespread use.

Portland was gassed at least 181 times between May 29 and July 15, according to research from the University of Portland. (Researchers believe this is an underestimate, and while tensions have eased since most federal officers left, gas continues to be used as of the writing of this article.) While many uses of tear gas occur after some protestors have gone home, the potential public health exposure to these chemicals has “innumerable implications for public health,” says Zoey Thill, a family medicine physician in New York and a fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health.

“Tear gas is inherently indiscriminate,” says Rohini Haar, an emergency physician and medical expert at Physicians for Human Rights. It wafts in the wind, stagnates in narrow streets and low elevations, and has been found to linger for weeks on surfaces nearly 1,000 feet away from where it was deployed, according to research conducted during pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong last year. Researchers there found CS residue on bike paths, walls of apartment buildings, and playgrounds. Those living near or in neighborhoods with protests, people who are homeless, and even those in jail have all reported feeling the effects of deployed tear gas.

Thill continues, “Putting aside the known bodily risks altogether—asthma exacerbations, arrhythmias, permanent vision changes or vision loss—the use of tear gas by police signifies an explicit commitment…to control and to repress.”

A “Rainbow of Health Concerns”

While plenty of studies have shown potential impacts of tear gas on respiratory, gastrointestinal, skin and eye health, the data on how it might affect reproductive health are sparse.

“It’s clear that we don’t have enough data and it’s hard to come by, as conducting studies—especially on reproductive health—would be unethical,” acknowledges Chloe Eudaly, a Portland city commissioner. Eudaly adds, “The fact that tear gas is a chemical weapon banned in war certainly suggests that it would be harmful to civilians.”

Haar agrees. “We don’t need a randomized controlled trial to know that tear gas is awful for you and that U.S. law enforcement recklessly uses this chemical weapon far too often.”

Anecdotal reports from Bahrain, the Gaza Strip, and Chile suggest that miscarriages and intrauterine fetal death increase in communities hit by tear gas. A Physicians for Human Rights survey conducted in the 1980s noted about 40 women’s babies in the Gaza Strip were stillborn, with the women reporting they noticed a lack of fetal movement two or three days after tear gas exposure.

The fact that tear gas is a chemical weapon banned in war certainly suggests that it would be harmful to civilians.

To fill in gaps in data, there are studies now investigating the possible connection between tear gas and disrupted menstrual cycles, including a University of Minnesota-Planned Parenthood North Central States survey focusing on exposure and reproductive health, and a Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research study about tear gas and overall health, both in initial stages.

Many women in Portland don’t need peer-reviewed research to convince them of the connection. Allison V., a 40-year-old mother and master’s student, says that her typically mild periods have gone haywire since she joined Black Lives Matter protests, first in Minneapolis and then in Portland. In the last few months, one period lasted only two and a half days; the next one arrived nine days late and lasted just a day and a half. “The gas is the only thing that has changed in my life,” she says. “I believe it’s directly related to the gas.”

Allison, who prefers not to use her full name, estimates she has breathed tear gas at least 30 times and describes gases of a variety of odors, densities, and colors, from green and red-pink to yellow and gray-white—“the whole rainbow of health concerns,” she says. (It’s hard to pinpoint exactly which chemicals are being used by U.S. law enforcement; the type and potency of these crowd control agents aren’t a matter of public record.)

“At first I thought I was crazy,” Allison continues. Then she stumbled across a Facebook post about strange period symptoms among protestors, from late and early cycles to extreme cramps and heavy bleeding. The post racked up 211 comments in three days.

Beyond Stress

One alternative explanation is that stress is to blame for erratic menstruation. Research shows high stress is linked to greater chances of irregular periods. (Uterine and cervical cancers, thyroid conditions, and polycystic ovary syndrome can also cause irregular periods.)

That’s what a doctor told Hester when she sought medical attention for a barrage of ailments, including twice-a-month periods, after being exposed to tear gas most days since May 29. “She told me that wasn’t symptoms of tear gas,” the activist says. “She said, ‘Oh, you could be stressed.’ I’m Black 24/7 and never had these symptoms before. They’re side effects of tear gas, point blank.”

Hester’s experience with a doctor who was quick to brush off her concerns aligns with what many Black people and other people of color know firsthand: That racial minorities are less likely to have access to quality and consistent health care, that medical providers are more likely to downplay Black patients’ pain, and that BIPOC face a variety of health outcomes worse than their white peers, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. With Black women leading many anti-racism movements, this could lead to a public health double-whammy: They endure more exposure to chemical agents yet have poorer medical care to treat that exposure.

Thill thinks Hester’s intuition is right, that her off-kilter cycle can’t be chalked up to only stress. “The usual stress response of the menstrual cycle is for things to sort of shut down. Ovulation can be delayed or can stop altogether,” she says. “The complaints I’m hearing with regard to tear gas exposure are of early periods, prolonged periods, or multiple periods in a month. These complaints can’t be explained by stress alone and are likely related to exposure to tear gas.”

The link could have an unintended chilling effect on activism. “Given that there is minimal evidence available about a link between tear gas exposure and irregular menstrual cycles, we run the risk of unintentionally intimidating women away from their right to protest and free expression,” Haar says.

So far, though, many activists are undeterred. “I keep going out there because Black lives matter at all costs,” Hester says. “If I lose my life, it’s fine, as long as you keep the work going on. You know we’re not going to stop. We’re going to fight.”

Related Story

Related Story

-

Bitten Lips Took Center Stage at Dior Fall 2024 Show

Bitten Lips Took Center Stage at Dior Fall 2024 ShowModels at the Dior Fall 2024 show paired bitten lips with bare skin, a beauty trend that will take precedence this season.

By Deena Campbell Published

-

30 Spring Items That Solve My Expensive-Taste-on-a-Humble-Budget Dilemma

30 Spring Items That Solve My Expensive-Taste-on-a-Humble-Budget DilemmaSee every under-$300 spring item on my wish list.

By Natalie Gray Herder Published

-

Your Makeup Won't Budge With These Setting Sprays

Your Makeup Won't Budge With These Setting SpraysPrepare for 12-hour wear.

By Sophia Vilensky Published

-

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"Senator and breast cancer survivor Amy Klobuchar is encouraging women not to put off preventative care any longer.

By Senator Amy Klobuchar Published

-

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My Body

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My BodyI'm plus size, but after I decided to pose nude for photos, I suddenly felt more body positive.

By Kelly Burch Published

-

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?Much like abortion, surrogacy, and IVF, becoming an egg donor was a reproductive choice that felt unfit for society’s standards of womanhood.

By Lauryn Chamberlain Published

-

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in Check

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in CheckGut health = wealth.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo Olympics

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo OlympicsShe withdrew from the event due to a medical issue, according to USA Gymnastics.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Truth About Thigh Gaps

The Truth About Thigh GapsWe're going to need you to stop right there.

By Kenny Thapoung Published

-

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” Condition

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” ConditionDespite having no outward signs, they can be brutal on the body and the mind. Here’s how each woman deals with having illnesses others often don’t understand.

By Emily Shiffer Published

-

The High Price of Living With Chronic Pain

The High Price of Living With Chronic PainThree women open up about how their conditions impact their bodies—and their wallets.

By Alice Oglethorpe Published