As a child in North Korea, the most isolated nation on the planet, Yeonmi Park knew nothing of the outside world. She learned only what her teachers taught: Americans were enemies and "bastards." At times, she and her classmates punched and kicked dummies dressed as U.S. soldiers. Food and electricity were scarce. Foreign films, illegal.

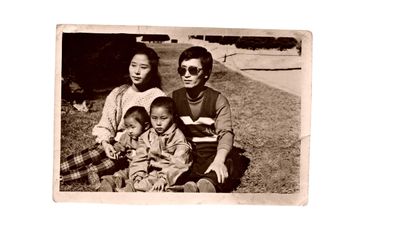

Park's father spent years in a labor camp for starting a business, which was not allowed by the government. When he got out, his bones protruding from hunger, the family decided to escape across the border to China. In 2007, with the help of smugglers, her older sister fled first, followed by Park and her mother, with her father due to come later. That's when their real problems began.

Marie Claire: Your sister vanished on her way to China. You and your mother got there but learned your smugglers were sex traffickers. Why had you trusted them?

Yeonmi Park: In North Korea, we never learned to think critically. There is no concept of individualism. The government treated us as less valuable than animals. You can't even stay overnight at someone's house without permission from the police. My mother warned me not to say—or even think—anything bad about our "dear leader," Kim Jong Il, because "even the birds and mice can hear you whisper."

MC: You were 13 at the time, and the traffickers said they wanted to rape you. Your mother said to rape her instead.

YP: She was raped two times that night. The first time, I heard only the sounds. The second time was in front of me. I told myself I did not see that. That's how I could carry on with life. It's a survivor trick.

MC: You learned that you and your mother would be sold to "husbands." How did it feel to hear that?

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

YP: I didn't know what human dignity meant. But I thought, You can't buy people for money. At that moment, I realized, Wow, you can be bought and sold. They were negotiating prices in front of us. It felt heavy, crushing. My mother and I were separated and sold to different men.

MC: You were sold to a man who tried to rape you. You fought him off, kicking and screaming. Where did you get that spirit?

YP: I don't know where that power came from. I was a small kid. We have a strength that we don't know. It comes out.

MC: He said he would help you track down your family, and you stopped fighting his sexual advances.

YP: Yes, I sensed some sincerity in this person, even though I fantasized about killing him. He did end up helping me find my parents.

MC: In late 2007, you and your parents reunited, but your father died the next year and you had to bury his ashes.

YP: That was the loneliest night. He had been through so much pain. When I saw him after he left the labor camp on sick leave, his voice was so oppressed. He couldn't look into people's eyes. He was so used to that—in prison, he wasn't allowed to look at the faces of the guards. He wasn't considered a person. Walking toward me, he looked so bony. His hair was shaved and bald. He was so sick, he had to be careful with what he ate because he hadn't eaten any ingredients like spice or oil when he was imprisoned. My mom was crying. But at that point, I didn't know how to be angry. I didn't know how to think for myself. Everything has to be taught—compassion, anger.

Yeonmi Park

MC: You heard Christian missionaries could help you get to freedom in South Korea through Mongolia. In 2009, you and your mother made it. What did the free world look like?

YP: Shiny! The airport was shining. The floor was shining. The ground was moving—a moving sidewalk. I saw girls in miniskirts, high heels, leather jackets. Their hair was dyed.

It was a different planet. There were flowers and trees. In North Korea, there is no color. You can feel that oppression, that misery. I remember being surprised when I saw trash cans in South Korea—people actually had garbage to throw away. In North Korea, we were so poor, we reused everything. We didn't throw anything away. If we used water to wash rice, we kept it. We used it to feed animals—pigs, dogs—or sometimes we washed our faces with it. We didn't have skin lotion or anything like that.

MC: What was it like to come across American "bastards" for the first time that year?

YP: I was very anxious. I didn't know what to expect. But when I saw them, I could see the truth. We were taught that they have cold blood, cold skin. Later, when my mother met my American coauthor, Maryanne Vollers, she said, "She's warm!"

MC: In 2013, your sister found her way to South Korea. How did it feel to see her?

YP: She was so small. She hadn't grown at all due to malnutrition and neglect. I grew, but she stopped. I thought, That beautiful girl, what did the world do to her? It takes a long time to recover. She's in the process.

MC: Your mother eventually went to retrieve your father's ashes from China.

YP: Yes, she brought him home. He's with us now in our room. He escaped North Korea too.

MC: When you began to speak publicly about your experience, the state-run media in North Korea released an ominous video calling you a "poisonous mushroom that grew from a pile of human waste."

YP: That was the first time I questioned if I should do this. I worried about my relatives in North Korea. But I cannot stop. People are so isolated there, they don't even know they're isolated. They don't know the words for "human rights." I believe North Korea will be free in our lifetime. Nothing is forever.

MC: How does it feel to wake up free every day in South Korea?

YP: Freedom is not quite natural to me. It takes a lot of energy to think freely. People ask for my opinion, and I think, Why does it matter? Or they ask my favorite food or color. I don't know my favorite food, but my favorite color is spring green. It's a journey to be free. I'm still learning it.

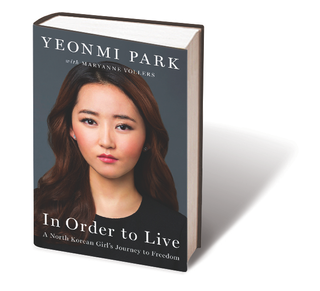

Yeonmi Park's memoir, In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl's Journey to Freedom, is available now. A version of this story appears in the November 2015 issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now.

Abigail Pesta is an award-winning investigative journalist who writes for major publications around the world. She is the author of The Girls: An All-American Town, a Predatory Doctor, and the Untold Story of the Gymnasts Who Brought Him Down.

-

This Week's Best On-Sale Picks Include a Tory Burch Bag and Pretty Silver Ballet Flats

This Week's Best On-Sale Picks Include a Tory Burch Bag and Pretty Silver Ballet FlatsWarm weather is finally here—it's time to dress like it.

By Brooke Knappenberger Published

-

A Sporty It-Sneaker Era Is About to Begin

A Sporty It-Sneaker Era Is About to BeginNike's next Air models are designed for Olympic athletes, but they'll soon be all over street style.

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

These Luxury Beauty Gifts Are Proven to Make Mom Feel Spoiled on Mother’s Day

These Luxury Beauty Gifts Are Proven to Make Mom Feel Spoiled on Mother’s DayThe best in makeup, haircare, and skincare for your favorite woman.

By Brooke Knappenberger Published

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenIt's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

EMILY's List President Laphonza Butler Has Big Plans for the Organization

EMILY's List President Laphonza Butler Has Big Plans for the OrganizationUnder Butler's leadership, the largest resource for women in politics aims to expand Black political power and become more accessible for candidates across the nation.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

Want to Fight for Abortion Rights in Texas? Raise Your Voice to State Legislators

Want to Fight for Abortion Rights in Texas? Raise Your Voice to State LegislatorsEmily Cain, executive director of EMILY's List and and former Minority Leader in Maine, says that to stop the assault on reproductive rights, we need to start demanding more from our state legislatures.

By Emily Cain Published

-

Your Abortion Questions, Answered

Your Abortion Questions, AnsweredHere, MC debunks common abortion myths you may be increasingly hearing since Texas' near-total abortion ban went into effect.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Future of Afghan Women and Girls Depends on What We Do Next

The Future of Afghan Women and Girls Depends on What We Do NextBetween the U.S. occupation and the Taliban, supporting resettlement for Afghan women and vulnerable individuals is long overdue.

By Rona Akbari Published

-

How to Help Afghanistan Refugees and Those Who Need Aid

How to Help Afghanistan Refugees and Those Who Need AidWith the situation rapidly evolving, organizations are desperate for help.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

It’s Time to Give Domestic Workers the Protections They Deserve

It’s Time to Give Domestic Workers the Protections They DeserveThe National Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, reintroduced today, would establish a new set of standards for the people who work in our homes and take a vital step towards racial and gender equity.

By Ai-jen Poo Published

-

The Biden Administration Announced It Will Remove the Hyde Amendment

The Biden Administration Announced It Will Remove the Hyde AmendmentThe pledge was just one of many gender equity commitments made by the administration, including the creation of the first U.S. National Action Plan on Gender-Based Violence.

By Megan DiTrolio Published