Piper Kerman: The Mistake That Nearly Cost Me Everything

After graduating from Smith College, Piper Kerman fell in with a hard-partying, drug-dealing crowd. Ten years after she left it all behind, her past came back to haunt her. In a Marie Claire exclusive, she reveals the true story that landed her 15 months in a federal prison.

International baggage claim in the Brussels airport was large and airy, with multiple carousels circling endlessly. I scurried from one to another, desperately trying to find my black suitcase. Because it was stuffed with drug money, I was more concerned than one might normally be about lost luggage.

Dressed in suede heels, black silk pants, and a beige jacket, I probably looked like any other anxious 24-year-old professional, a typical jeune fille, not a bit counterculture, unless you spotted the tattoo on my neck. I had done exactly as I had been instructed, checking my bag in Chicago through Paris, where I had to switch planes to take a short flight to Brussels.

When I arrived in Belgium, I looked for my black rollie at the baggage claim. It was nowhere to be seen. Fighting panic, I asked in my mangled high school French what had become of my suitcase. "Bags don't make it onto the right flight sometimes," said the big lug working in baggage handling. "Wait for the next shuttle from Paris — it's probably on that plane." Had my bag been detected? I knew that carrying more than $10,000 undeclared was illegal, let alone carrying it for a West African drug lord. Maybe I should try to get through customs and run? Or perhaps the bag really was delayed, and I would be abandoning a large sum of money that belonged to someone who could probably have me killed with a simple phone call. I decided that the latter choice was slightly more terrifying. So I waited.

The next flight from Paris finally arrived — I spotted the suitcase. "Mon bag!" I exclaimed in ecstasy, seizing the Tumi before sailing through one of the unmanned doors into the terminal, inadvertently skipping customs. There I spotted my friend Billy waiting for me. I didn't breathe until we had pulled away from the airport and were halfway across Brussels.

I graduated from Smith College, class of '92, on a perfect, sun-dappled New England day. While my more organized and goal-oriented classmates set off for graduate school programs or entry-level jobs, I decided to stay on in Northampton, Massachusetts. A well-educated young lady from Boston with a thirst for bohemia, I had no idea what to do with all my longing for adventure. So I got an apartment with a fellow Smithie and a job waiting tables at a microbrewery. I bonded with fellow waitresses, bartenders, and musicians, all equally nubile and constantly clad in black. I ran for miles on country lanes, learned how to carry a dozen pints of beer up steep stairs, and indulged in numerous romantic peccadilloes with appetizing girls and boys.

My loose social circle included a clique of impossibly cool lesbians in their mid-30s. Among them was Nora Jansen, a short, raspy-voiced Midwesterner who looked a bit like a white Eartha Kitt. Nora was the only one of that group of older women who paid any attention to me. One night over drinks, she calmly explained to me that she had been brought into a drug-smuggling enterprise by a friend of her sister, who was the lover of a major West African drug kingpin named Alaji. Nora was trafficking heroin into the U.S. and was being paid handsomely for her work. I was completely floored. Why was she telling me this? What if I went to the police? It all sounded dark, awful, scary, wild — and exciting beyond belief, a world about which I knew nothing. And while it wasn't exactly love at first sight, for a 22-year-old in Northampton looking for adventure, Nora was a figure of intrigue. As if by revealing her secrets to me, Nora had bound me to her, and a secretive courtship began.

Over the months that followed, we grew much closer. When she was in Europe or Southeast Asia for a long period of time, I all but moved into her house, caring for her beloved black cats, Edith and Dum-Dum. One day Nora returned home with a new white Miata convertible and a suitcase full of money. She dumped the cash on the bed and rolled around in it, naked and giggling. Soon I was zipping around in that Miata, with Lenny Kravitz demanding to know, "Are You Gonna Go My Way?"

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

At the end of the summer, Nora learned that she had to return to Indonesia. "Why don't you come with me, keep me company?" she suggested. Although I had been yearning to make a move to California, I had never been out of the United States, and the prospect was irresistible. I wanted an adventure, and Nora had one on offer. It was that simple. What would I need for my journey to Indonesia? I had no idea. I packed a small L.L. Bean duffel bag with a tank dress, blue jean cutoffs, some T-shirts, and a pair of black cowboy boots. I was so excited, I forgot a bathing suit. Adopting an air of mystery, I told my parents that I was traveling for an art magazine, then rebuffed any of their questions.

Bali was a bacchanalia: days and nights of sunbathing, drinking, and dancing until all hours. Expeditions to temples, parasailing, and scuba diving offered other diversions — the Balinese scuba instructors loved the long-finned, elegant blue fish that had been tattooed on my neck while I was in New England.

But the festivities were always punctuated by tense phone calls between Nora and her drug contacts. As a go-between for Alaji, she arranged to smuggle suitcases with heroin sewn into the lining into the States. It was up to her to figure out how to coordinate the logistics — recruiting couriers, training them on how to get through customs undetected, paying for their "vacations" and fees. The job required lots of flexibility and lots of cash. When funds ran low, I was sent off to retrieve money wires from Alaji at various banks — a crime itself, although I did not realize it.

During a brief stay back in the States to visit with my very suspicious family, I received a call from Nora, who explained tersely that she needed me to fly out the next day, carrying cash to be dropped off in Brussels. She had to do this for Alaji, and I had to do it for her. She never asked anything of me, but she was asking now. Deep down I felt that I had signed up for this situation and couldn't say no. I was scared and agreed to do it.

Nora met up with me in Europe, where things took a darker turn. Her business was getting harder for her to maintain, and she was taking reckless chances with couriers, which was a very scary thing. When Nora informed me that she also wanted me to carry drugs, I knew that I was no longer valuable to her unless I could make her money. Obediently I "lost" my passport and was issued a new one. She costumed me in glasses and pearls and told me to get a conservative haircut. With makeup she tried in vain to cover up the tattoo on my neck.

A single phone call to my family would have rescued me from this mess of my own making, yet I never placed that call — I thought I had to tough it out on my own. Mercifully, the drugs she wanted me to carry never showed up, and I narrowly avoided becoming a drug courier. Still, it seemed like only a matter of time before disaster would strike. I was in way over my head and knew I had to escape. When Nora and I got back to the States right before Thanksgiving, I took the first flight to California I could get. From the safety of the West Coast, I broke all ties with Nora and put my criminal life behind me.

It took me a while to get used to a normal life. I had been living on room service, exoticism, and anxiety for over six months. But several friends from college, now in the Bay Area, took me under their wing, pulling me into a world of work, barbecues, softball games, and other wholesome rituals. I immediately got two jobs, rising early in the morning to open a juice bar in the Castro, and getting home late at night after hostessing at a swank Italian restaurant across town. Finally I landed a "real" job at a TV production company that specialized in infomercials and worked my way up from gal Friday to producer.

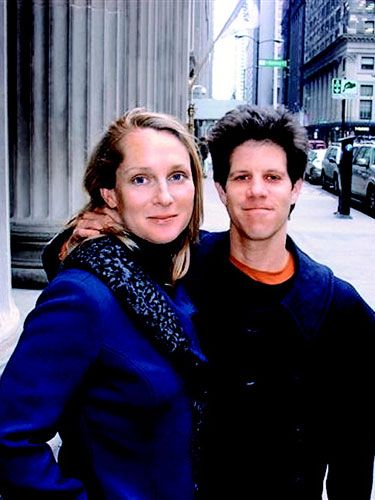

I never talked about my involvement with Nora to new friends, and the number of people who knew my secret remained very small. As time passed, I gradually relaxed — I was feeling pretty damn lucky. Great job, great city, great social life. Through mutual friends, I met Larry, the only pal I knew who worked as much as I did in leisure-loving San Francisco. When I would crawl, exhausted, out of the editing room after hours, I could always count on Larry for a late dinner or later drinks. We shared a particularly simpatico sense of humor, and he quickly became the most reliable source of fun that I knew. Within months we were an official couple, much to the shock of our skeptical friends. When Larry got offered a great magazine gig back East, I quit my beloved job to move back with him. More than four years after I parted ways with Nora, Larry and I landed in New York in 1998 — he was an editor at a men's magazine, I worked as a freelance producer — and settled in a West Village walk-up.

One warm May afternoon, as I worked from home in my pajamas, the doorbell rang. Within minutes, two customs officers were standing in my living room, informing me that I'd been indicted in federal court in Chicago on charges of drug smuggling and money laundering, and that I'd have to appear in court within the month or be taken into custody. The veins in my temples suddenly pounded as if I had run miles at top speed. I had put my past behind me, had kept it secret from just about everyone, even Larry. But that was over. I was shocked at how physical my fear was.

I staggered uptown to Larry's office and pulled him out onto the street. "I've been indicted in federal court for money laundering and drug trafficking."

"What?" He looked amused, as if perhaps we were participating in some secret street theater.

"It's true. I'm not making it up. I just came from the house. The Feds were there."

Larry was uncharacteristically quiet. He didn't yell at me for not telling him I was a former criminal, didn't chastise me for being a reckless, thoughtless, selfish idiot. He never once suggested that, as I emptied my savings account for legal fees and bond money, perhaps I had ruined my life — and his, too. He said, "It will all work out. Because I love you."

That morning was the beginning of a long, torturous expedition through the labyrinth of the U.S. criminal justice system. Confronted with the end of my life as I knew it, I closed myself off, telling myself that I would have to figure out a solution on my own. But I wasn't alone — my family and my unsuspecting boyfriend came along for the miserable ride. My father arrived in New York, and we drove an excruciating four hours up to New England for an emergency family meeting at my grandparents' home. I sat in their living room rigid with shame while they questioned me for hours. What I had done was almost totally beyond their comprehension.

Incredibly, my family said they loved me and would help me. Still, they doubted that a "nice blonde lady" like me could ever end up in prison. But my lawyer, referred to me by the biggest big-shot lawyer I knew, quickly impressed upon us the severity of my situation. My indictment in federal court for criminal conspiracy to import heroin had been triggered by the collapse of my ex-lover's drug-smuggling operation. Nora was in custody, pointing fingers and naming names. Gently but firmly, my lawyer explained that if I wished to go to trial and fight the conspiracy charge, I would be one of the best defendants he had ever worked with, sympathetic and with a story to tell; but if I lost, I risked the maximum sentence, well over a decade in prison. If I pleaded guilty, make no mistake, I was going to prison under mandatory minimum sentencing beyond any judge's control, but for a much shorter time. There were some agonizing conversations with Larry and my still-reeling family before I chose the latter.

In October 1998, with Larry looking on, I stood tall, if pale, in my best suit in Chicago's federal court building and choked out three words that sealed my fate: "Guilty, Your Honor." But shortly after, my date with prison was postponed indefinitely after Alaji, the West African drug kingpin, was arrested in London and the U.S. tried to extradite him to stand trial. The Feds wanted me in street clothes, not an orange jumpsuit, to testify against him. There was no end in sight.

I spent the next five years under federal supervision, reporting monthly to my "pretrial supervisor," an earnest young woman with an exuberantly curly mullet and an office in the federal court building in Manhattan. Every now and then I was drug-tested — I always tested clean. My predicament remained a secret from almost everyone I knew — friends, colleagues, employers. I felt that I just had to gut it out quietly. My friends who did know were mercifully quiet on the subject as the years dragged on.

I worked hard at forgetting what loomed ahead, pouring my energies into exploring New York with Larry and our friends. I needed money to pay my huge, ongoing legal fees, so I worked as an online creative director with clients my hipster colleagues found unpalatable: big telecom and petrochemical firms, shadowy holding companies. With folks who knew nothing of my criminal secret and looming imprisonment, I was simply not quite myself — pleasant, but aloof, distant. Somewhere on the horizon was coming devastation, the arrival of Cossacks and hostile Indians.

As the years passed, my family began to believe that I would be miraculously spared. But never for a minute did I allow myself to indulge in that fantasy — I knew that I would go to prison. But the revelation was that my family and Larry still loved me despite my massive fuckup; that my friends who knew my situation never turned away from me; and that I could still function in the world professionally and socially, despite having ostensibly ruined my life. I began to grow less fearful about my future, my prospects for happiness, and even about prison.

Ultimately, Britain declined to extradite Alaji to America and, instead, set him free. Finally, more than five years after I pleaded guilty, the U.S. Attorney in Chicago was willing to move forward with my case. To prepare for my sentencing, I wrote a personal statement to the court and broke my silence with more friends and coworkers, asking them to write letters to the judge vouching for my character. It was an incredibly humbling experience to approach people I had known for years, confess my situation, and ask for their help. I had steeled myself for rejection, knowing that it would be perfectly reasonable for someone to decline on any number of grounds. Instead, I was overwhelmed by kindness and cried over every letter, whether it described my childhood, my friendships, or my work ethic. Each person strived to convey what they thought was important and great about me, which flew in the face of how I felt: profoundly unworthy.

Finally my sentencing date drew near. Larry and I again flew to Chicago where we hoped for a shorter sentence in light of the lengthy delay. At the advice of my lawyer, I wore a skirt suit from the 1950s that I had won on eBay, cream with a soft blue windowpane check, very country club. "We want the judge to be reminded of his own daughter or niece when he looks at you," my lawyer said.

On December 8, 2003, I stood in front of Judge Charles Norgle with a small group of my family and friends sitting behind me in the courtroom. Before he handed down my sentence, I made a statement. "Your Honor, more than a decade ago I made bad decisions, on both a practical and a moral level. I acted selfishly, without regard for others. I am prepared to face the consequences of my actions and accept whatever punishment the court decides upon. I am truly sorry for all the harm I have caused to others."

I was sentenced to 15 months in federal prison, and I could hear Larry, my parents, and my friend Kristen crying behind me. We returned to New York where the wait continued, this time for my prison assignment. It felt oddly like waiting for my college acceptance letter — I hope I get into Danbury in Connecticut! The next closest federal women's prison was in West Virginia, 500 miles away. When the thin envelope arrived from the federal marshals a few weeks after my sentencing, telling me to report to the Federal Correctional Institution in Danbury on February 4, 2004, my relief was overwhelming.

I tried to get my affairs in order, preparing to vanish for over a year. I had already read the books on Amazon about surviving prison, but they were written for men. About a week before I was to report, Larry and I met a small group of good friends at a bar for a very impromptu going-away. We had a good time — shot pool, told stories, drank tequila. Night turned into morning, and finally one friend had to say good-bye. And as I hugged him as hard and relentlessly as only a girl drunk on tequila can, it sank in on me that this was really good-bye. I didn't know when I would see any of my friends again or what I would be like when I did. And I started to cry. I had never wept in front of anyone but Larry. But now I cried, and then my friends started to cry. We must have looked like lunatics, sitting in an East Village bar at 3 in the morning, sobbing.

On February 4, 2004, more than a decade after I had committed my crime, Larry drove me to the women's prison in Danbury. We had spent the previous night at home; Larry had cooked me an elaborate dinner, and then we curled up in a ball on our bed, crying. Now we were heading much too quickly through a drab February morning toward the unknown. As we made a right onto the federal reservation and up a hill to the parking lot, a hulking building with a vicious-looking triple-layer razor-wire fence loomed. If that was minimum security, I was fucked. Almost immediately, a white pickup with police lights on its roof pulled in after us. I rolled down my window. "There's no visiting today," the officer told me. I stuck my chin out, defiance covering my fear. "I'm here to surrender."

Follow Marie Claire on Facebook for the latest celeb news, beauty tips, fascinating reads, livestream video, and more.