This story is a follow-up to MarieClaire.com's special report Women and Guns: The Conflicted, Dangerous, and Empowering Truth. Stay tuned this week as we publish Women and Guns response pieces and new material that sheds light on the nuanced world of females and firearms. Join the conversation on social media with the hashtag #WomenAndGuns.

When I was 9 years old, just a skinny little pipsqueak of a girl, I watched my father point a shotgun at my mother's head.

I grew up in New Hampshire in the 1960s, in a housing project apartment with more guns than rooms. There were shotguns for hunting. Hand guns for target practice. And a "lowlife special," as my father called it, tucked under my parents' mattress, to teach any lowlife who might break in a lesson.

There were quite a few lowlifes around our place at that time. My father sold stolen merchandise—anything from RCA TVs to Gillette razor blades. He also sold 8mm porn films that he code-named "pancakes" to clean-cut family men from the nice part of town.

"My father never locked his guns up. Never. It would've been like locking up the Rice Krispies."

My father never locked his guns up. Never. It would've been like locking up the Rice Krispies.

I knew I wasn't supposed to play with them. "A gun's not a toy," he told me a bunch of times. But I never really bought it. Especially not after watching him kid around with guns himself. Like the time he pointed one at the TV and pretended to blow away Lawrence Welk. That really cracked me up—I couldn't stand polka music, either.

When no one was around, I used those guns to play cops and robbers. Sometimes I was the cop, more often the robber. It was way more fun being the robber. "Stick 'em up!""Hand over the dough!" I liked ordering imaginary grown-ups around. You get sick of being ordered around by the real ones when you're a kid.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

All the time I was playing with those guns, I didn't know whether they were loaded. Some of them were and some of them weren't. It didn't seem to matter. I was having too much fun to even think about it.

I suppose if I'd been given toy guns I would've played with them instead. But I was a girl, and girls were given Barbies and Easy-Bake ovens. (Or, once in a while, a stolen bicycle.)

I was never a very good shot. I had lousy vision, which I didn't let on about so I wouldn't get stuck wearing glasses and being called four-eyes. With my crummy eyesight, I should never have been handling a gun in the first place. Especially not the day my father went ballistic.

"All the time I was playing with those guns, I didn't know whether they were loaded."

The day began like any other Saturday. I'd been watching cartoons. Wile E. Coyote. Yosemite Sam. I was what you might call a cartoon addict. I preferred animated characters to real people.

My mother came home from working the nightshift in a sunglass factory. She was late because she'd been working overtime to earn extra money. My father didn't buy it. When he'd been drinking, nobody could convince him of anything. He knew best even though he couldn't see straight himself.

He accused my mother of fooling around. Then he went and got his rifle.

Suddenly, I turned into Mighty Mouse. It was up to me to save the day. I ran to the hall closet and grabbed a pistol. This was no longer make-believe. The gun felt heavier than I remembered. My skinny arms shook. My fuzzy vision seemed fuzzier through the tears.

I walked to the kitchen where my mother was standing frozen by the stove, my father a few feet away, his finger on the trigger. They didn't even know I was there.

I felt a scream fill my mouth. I clamped my lips tight, afraid my voice would startle him and that the gun pointed squarely at my mother would go off. Then wouldn't it be all my fault if she got shot?

My mind was exploding with coulda, shoulda, and woulda. I coulda stopped this from happening. I shoulda been in the kitchen, not watching stupid cartoons. I woulda explained to my father that my mother was working late so she could pay for a toy I'd seen advertised on TV and wanted so badly it hurt.

But it was too late for explanations.

We weren't a church-going type family, but I'd heard about God from kids on the playground and so I prayed. Please God, make him stop. Please God, don't let her die. Please God, do something.

My mother's face was as white as I imagined heaven to be. My father, like an angry god, held her fate in his hands. They were saying stuff that I could barely hear with all the blood pounding in my ears.

I raised the gun. I knew one of them had to go. Him or her. There was no good choice. No happy ending. No funny ha ha cartoon death.

I prayed I wouldn't miss. Prayed God would save me. Prayed somebody would save me.

"I knew one of them had to go. Him or her. There was no good choice."

And then—halleluiah!—someone did. A friend of my father's walked through the front door and grabbed the shotgun. He checked the barrel. It was loaded.

He yelled at my father. And my father slumped into a chair.

That man stopped my father from making the biggest mistake of his life. At least I think he did. But I'll never really know for sure. Maybe my father was just fooling around. Maybe he was just trying to teach my mother a lesson she'd never forget. That's what he said later when he'd sobered up. But I don't think he knew himself if he would've pulled the trigger.

As for me, I held onto that pistol until the coast was clear. Then I put it back in the closet. I hid it as best as I could under the ice skates and galoshes. Hid it so maybe he couldn't find it.

I went back to watching cartoons, but they weren't as funny.

Gloria as the author of the memoir KooKooLand.

This story is a follow-up to MarieClaire.com's special report Women and Guns: The Conflicted, Dangerous, and Empowering Truth. Join the conversation on social media with the hashtag #WomenAndGuns.

-

Anne Hathaway Details the "Gross" Audition Request She Once Endured

Anne Hathaway Details the "Gross" Audition Request She Once Endured"Now we know better."

By Meghan De Maria Published

-

The Emotional Ending of 'Baby Reindeer,' Explained

The Emotional Ending of 'Baby Reindeer,' ExplainedNetflix's latest miniseries from Richard Gadd is based on the true story of the comedian and his stalker.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

The Must-Visit Hair Colorists in New York City

The Must-Visit Hair Colorists in New York CityI trust these talented colorists implicitly.

By Sophia Vilensky Published

-

Yes, Caregiving Is Essential Infrastructure

Yes, Caregiving Is Essential InfrastructurePresident Biden’s American Families Plan is further proof that care is necessary for economic growth.

By Valerie Jarrett Published

-

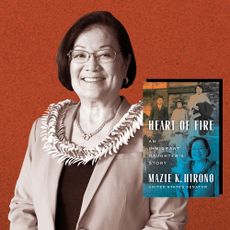

Senator Hirono on Her Journey to the U.S. Senate and Having a "Heart of Fire"

Senator Hirono on Her Journey to the U.S. Senate and Having a "Heart of Fire"At first glance, 'Heart of Fire' is a political memoir. At its core, it's an ode to a mother who changed her daughter's life.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

Solidarity & Solutions: Asian American Women on Where to Go From Here

Solidarity & Solutions: Asian American Women on Where to Go From HereSen. Mazie Hirono, Lana Condor, Tina Tchen, and more on what it will take to create meaningful change in this country.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

To Her Stepchildren, Kamala Harris Is "Momala"

To Her Stepchildren, Kamala Harris Is "Momala""They are my endless source of love and pure joy," she's said.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Who Are Joe Biden's Grandchildren, Who Range from Seven Months Old to 26?

Who Are Joe Biden's Grandchildren, Who Range from Seven Months Old to 26?He has seven!

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Who Is Maya Harris, Kamala Harris' Super-Supportive Sister?

Who Is Maya Harris, Kamala Harris' Super-Supportive Sister?Maya worked for Hillary Clinton in 2016 as a senior advisor.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

AOC on the Capitol Attack: "I Thought I Was Going to Die"

AOC on the Capitol Attack: "I Thought I Was Going to Die"The congresswoman opened up about the traumatic day in an Instagram live.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

10 Years After Her Shooting, Gabby Giffords Still Has Hope

10 Years After Her Shooting, Gabby Giffords Still Has HopeThe former congresswoman and gun control advocate shares how she's chosen to move forward amid the pain and trauma she’s faced.

By Gabby Giffords Published