The Entrepreneur: Jean Brownhill Lauer, 38

Lauer is the Brooklyn-based founder of Sweeten, a startup that connects home renovators with vetted contractors. Since its 2011 founding, the company has raised $4.3 million in funding and completed 500 major renovations, and currently features $300 million in projects on its site. Here's how Lauer turned her home-design obsession into a thriving enterprise—and how she went from making ends meet to mogul in the making.

Growing up, I lived with my mom in New London, Connecticut; I never felt really broke, but then I think back on how many times I had to push-start my mother's car because she couldn't afford a new starter. There were actual crack houses a few doors down from my house. Only later did I realize how resilient that experience made me. I've seen a lot of people who are used to the door being open, and if it's not, they give up. But I'm used to the door being locked. I'll try the window, the fire escape, climb onto the roof, maybe go down the chimney. To me, it's always like, They're not coming to cut off the electricity yet? We're fine.

"They're not coming to cut off the electricity yet? We're fine."

I knew I wanted to go into architecture because I was always doing little projects to make our house nicer. I wanted a new couch, so when I was 13 or so, I went to the local furniture store every week and gave them my babysitting money on layaway until finally I had paid it off. We had that couch in our living room until my mom moved 15 or so years later.

We had no money for college. My mother found Cooper Union in one of those College for Dummies books and was like, "Oh, you should go here—it's free." Luckily, I had the grades, and the home test was right up my alley. On a piece of paper, you had to draw a highway that you could not drive on. Some people did M.C. Escher drawings. I took the paper, put it in our driveway, and drove over it as many times as I could to get a bunch of tire tracks on it. Then I wrote an essay about how there was nothing that I could draw that couldn't be driven on.

After graduation, I went to work for Elizabeth O'Donnell, a dean with a small architecture firm. She gave me a huge amount of responsibility for someone who had just graduated. But I was fearless. I was like, "Sure, I'll do it."

After that, I was hired as a draftsperson at Coach working in the global architecture department. The group designed all the stores and elements, like tables. I was very junior when I went to the VP of the department and told him we needed an [internal] website to help us streamline all of our projects and save money. He told me to pitch it to the COO, that if I could get the money and not slack on my regular responsibilities, I could go for it. The site was built in nine months. For the next four years, I built websites that made our construction and merchandising groups more efficient.

I had known for a while that I wanted to do something more entrepreneurial, and then one day I found out that a young man in our department was making $40,000 more than me, even though I was a senior manager and he was just a manager. That was the last straw.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

I had gotten a nice bonus from work and bought a wood-frame house from the 1800s in Brooklyn's Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. It needed a full gut renovation, but it was really hard to find a general contractor—and I'm in the industry! I used all the resources available online—reviews, websites—and still ended up hiring the wrong [people]. So I started devising ideas for Sweeten—as in "home sweet home"—as early as 2008. (It wouldn't go live until 2011.) Meanwhile, I had become this evangelist for the Internet and architecture, and was running around town giving talks. At the end of one, a woman came up to me and said, "I don't know if you've ever heard of a Loeb Fellowship, but I want to nominate you."

They find people who are doing really interesting things and give them all of the resources that Harvard has to offer. You don't have to do homework—your only responsibility is that you have to promise to change the world for the better. Every year, hundreds of people get nominated and only nine get it. I was super-fortunate to get in. It absolutely changed the course of my life.

I finished the fellowship in May 2012 and have been focused on Sweeten full-time since then. For the first year and a half, we were doing very small projects—our average project size was just $2,000. I wasn't sure if it was going to work. Then we got picked up by New York magazine as the Best Contractor Locator and the demand went through the roof. That was the turning point that told me Sweeten could be something really huge. Today, I have 20 employees, which I couldn't even have imagined in my wildest dreams when I started out.

I hope that a lot more African-American females choose to do entrepreneurial endeavors that aren't haircare- or beauty-related. And I hope that kids who come from backgrounds similar to mine realize that they're actually getting an incredible education in how the world really works. I'm a millionaire on paper, based on what my company is worth, but I don't actually make that much. Still, I make way more than my parents ever made probably in their whole careers, and I'm so far from where I started that I feel like I've already made it.

Jean Brownhill Lauer's startup, Sweeten, recently secured $4.3 million in funding.

The Money Manager: Elle Kaplan, 35

Kaplan is the founder and CEO of LexION Capital, a money-management firm that handles over $100 million for more than 55 families. Here, she tells her story of arriving in New York with just $200 and plans to conquer Wall Street.

I grew up comfortably in the Midwest, the third of four children. My dad was a lawyer and my mother stayed home. When I was a small child, I watched Mary Poppins: The children want their tuppence to feed the birds. But I thought they should have left their tuppence in a bank earning interest. They could have bought a ton more birdseed that way.

Then my father fell into a nonresponsive coma when I was in college. My mom would sit at the kitchen table, crying about how overwhelmed she was with the finances, that she didn't know where anything was. I felt awful, and I wanted to help, so I began focusing my reading on learning everything I could about financial management and investing.

I learned that Wall Street was a buyer-beware world. Brokers operate like pharmaceutical salespeople, not like doctors. They can recommend anything, and it doesn't have to be in your best interest. It's just whatever they're selling. Then I learned that there are investment advisers who must act like doctors, in accordance with something called the fiduciary standard. Learning that changed the course of my life.

"I had saved up $200 and slept on the floor of my mom's friend's apartment in Westchester."

When I finished college, I set off for New York City with plans to one day open up a fiduciary firm that could help women like my mom, who is brilliant, but just doesn't know this space. I had saved up $200 and slept on the floor of my mom's friend's apartment in Westchester. I took the train into the city to temp while trying to get a job, which I assumed would be easy given my A averages in English and chemistry. But nobody would even interview me. Headhunters were all incredibly discouraging because I had no internships or background in finance.

Then I got my lucky break when I was called in to interview as a receptionist for The Beacon Group, a financial services company. Turns out, they had an opening for an analyst. They asked me some math and logic questions, and I ended up getting that job a few weeks later. When you're entry-level on Wall Street, you live at the firm. You're eating three meals a day there, and sometimes pulling all-nighters. A lot of my coworkers had gone to Princeton, and wore fancy cuff links and monogrammed shirts, while I was shopping at discount stores. Once I got to know them, everyone was wonderful. But it was terrifying at first.

Beacon was eventually acquired by JPMorgan Chase, at which point I started going to Columbia for my executive MBA. I worked full-time while I went to school. I didn't have time for friends or dating, or even cooking meals or sleeping. It was all very good training for launching my own firm.

I quit my job and started LexION in October 2010. Around 2 p.m. on the day I launched, I e-mailed people I knew [prospective clients], and by 5 p.m., I had heard back from everyone—they all wanted to come. That was it. I was astounded. I had so much success that at the end of that day, I stopped accepting clients for the next six months.

Since then, LexION has grown organically. We don't have a sales team. Our growth is entirely due to word of mouth. I own 100 percent of the firm. I've taken no outside capital, ever, and have even turned it down a number of times. I worry that when you take someone else's money, you have to incorporate their vision, and I want to make sure that we stay very pure to our own mission, which is putting people before profits.

For my next act, I want to teach other women how to think like entrepreneurs, whether they're building a team within a firm or creating their own company. I have a book coming out, called Love the Hustle, where I encourage and inspire women to dream big and make that first million themselves—and not let anyone else's narrow view of the world alter their goals.

Elle Kaplan runs the only 100 percent woman-owned asset management firm in the U.S.

The Executive: Kat Cole, 37

The former Hooters waitress is a college dropout who eventually became president of Cinnabon. Today, Cole is group president of Cinnabon's parent company, Focus Brands, overseeing Auntie Anne's, Carvel, McAlister's Deli, and Schlotzsky's.

My father was a sweet and kind man, but he was an alcoholic and a terrible husband and father. When I was 9, my mom decided we were leaving. It had been bad for a while. I remembered thinking I would rather mow the lawn or clean the roof than live like that.

My mother had an entry-level job and no real resources to depend on. She fed us potted meat and beanie weenies. I don't remember ever feeling like we were going without. I loved potted-meat-and-mustard sandwiches and frozen-lasagna night. My mom worked odds and ends; then she founded this company that did in-home wine-tasting parties. We grew up in Jacksonville, Florida, which is not necessarily known for its exotic wine culture. My mom didn't go to college. She didn't have a background in food and wine. She just knew someone who did this and said, "Oh, I can do that." Not only did it help her make money, but she really enjoyed it, too.

At 15, I started working in a gym, cleaning equipment. I also began selling clothes in a mall. At 16, I was one of the top salespeople in the company. When I turned 17, I became a Hooters hostess and kept all three jobs until I turned 18 and became a Hooters girl. The income from that was enough so that I could quit the other jobs and still save plenty for college. On weekends, I might walk out with over $300 in a day. I set the record for open/closes—you work the opening shift through the closing shift and come back to do it all again the next day. I did it for 21 days straight.

I loved working and always felt the need to be helpful. When the cooks quit, I went into the kitchen and helped finish. If a bartender needed a hand, I was the one who would jump in. One day when I was 19, my general manager came to me and said, "The corporate office called. They are opening the first-ever Hooters in Australia. They are looking for the best employees who know how to work every job in the restaurant. I really think you would be an incredible person to go." I ended up being part of that team to go over and wound up running all employee training for the company by the time I was 20.

That meant having to go to different countries every week with different teams, which taught me how to build trust quickly. I would be in Australia with a team of people whom I had never met before. Then I would leave from Australia to go to Mexico. Then when I was in Argentina, I was with a different team. I had to do things like bring them doughnuts and coffee and find common ground quickly. But I also had to solve problems, know when to take a stand, and when to be flexible.

"Show me another company that would have given the college-dropout child of an alcoholic and a single parent the opportunities I got."

I often tell people, "Show me another company that would have given the college-dropout child of an alcoholic and a single parent the opportunities I got." The reality is they would not. Why did Hooters give me those opportunities? I don't care why the door got opened. I just walked through it. I was there for more than 15 years, and the things I learned there have made me a better leader.

I took over Cinnabon at the tail end of the recession. The business was not performing well, but the brand was beloved. We launched new Cinnabon-branded products like creamers and desserts, and hit the billion-dollar mark in sales, which was a huge milestone.

But I hope people see beyond the corporate side of my story. I hope they look at how I have invested in communities over the years, the fact that I spend so much of my time with nonprofits and small businesses, that I spend time in Atlanta [where Focus Brands is headquartered] helping to make that city a better place.

I had a mentor once ask me, "Who do you think you are?" I said, "What do you mean?" She said, "You've been given a gift. You have the ability to influence. You seem to be able to straddle multiple worlds—a creative community and a conservative business community. How dare you not put that to its best use?"

I hope my story inspires people to find their own "candlepower"—that ability to keep the candle burning bright no matter how hard the wind blows. Whether they're having a tough day, trying to build something, start a company, move up in their own business, or just do something cool for their family, I want people to realize that they are capable of more than they could ever imagine.

During her tenure as president of Cinnabon, Kat Cole presided over $1 billion in sales.

This article appears in the November issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands October 20.

Follow Marie Claire on Instagram for the latest celeb news, pretty pics, funny stuff, and an insider POV.

-

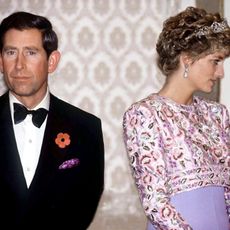

Princess Diana Revealed to a Royal Author the Real Reason Why Her Marriage to Prince Charles Ended Not Long Before She Died in 1997

Princess Diana Revealed to a Royal Author the Real Reason Why Her Marriage to Prince Charles Ended Not Long Before She Died in 1997And no, it apparently wasn’t Camilla Parker-Bowles.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Princess Martha Louise of Norway Sets Wedding Date with Fiancé Shaman Durek Verrett After a Two Year Engagement

Princess Martha Louise of Norway Sets Wedding Date with Fiancé Shaman Durek Verrett After a Two Year EngagementAlready billed as “one of the most beautiful high society weddings of the year,” the celebration will last for four days.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Heidi Gardner Opens Up About Viral Moment She Broke Character During ‘Saturday Night Live’ Beavis and Butt-Head Sketch

Heidi Gardner Opens Up About Viral Moment She Broke Character During ‘Saturday Night Live’ Beavis and Butt-Head Sketch“I just couldn’t prepare for what I saw.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Peloton’s Selena Samuela on Turning Tragedy Into Strength

Peloton’s Selena Samuela on Turning Tragedy Into StrengthBefore becoming a powerhouse cycling instructor, Selena Samuela was an immigrant trying to adjust to new environments and new versions of herself.

By Emily Tisch Sussman Published

-

This Mutual Fund Firm Is Helping to Create a More Sustainable Future

This Mutual Fund Firm Is Helping to Create a More Sustainable FutureAmy Domini and her firm, Domini Impact Investments LLC, are inspiring a greater and greener world—one investor at a time.

By Sponsored Published

-

Power Players Build on Success

Power Players Build on Success"The New Normal" left some brands stronger than ever. We asked then what lies ahead.

By Maria Ricapito Published

-

Don't Stress! You Can Get in Good Shape Money-wise

Don't Stress! You Can Get in Good Shape Money-wiseYes, maybe you eat paleo and have mastered crow pose, but do you practice financial wellness?

By Sallie Krawcheck Published

-

The Book Club Revolution

The Book Club RevolutionLots of women are voracious readers. Other women are capitalizing on that.

By Lily Herman Published

-

The Future of Women and Work

The Future of Women and WorkThe pandemic has completely upended how we do our jobs. This is Marie Claire's guide to navigating your career in a COVID-19 world.

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

Black-Owned Coworking Spaces Are Providing a Safe Haven for POC

Black-Owned Coworking Spaces Are Providing a Safe Haven for POCFor people of color, many of whom prefer to WFH, inclusive coworking spaces don't just offer a place to work—they cultivate community.

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

Where Did All My Work Friends Go?

Where Did All My Work Friends Go?The pandemic has forced our work friendships to evolve. Will they ever be the same?

By Rachel Epstein Published