My Healing Journey After Sexual Assault

To recover from an assault at the hands of a friend, I spent months experimenting with different therapies.

In October of 2017, during the height of #MeToo, I was sexually assaulted by my roommate. We’d been living together about seven months, and in that time he’d quickly become one of my best friends. I’d been assaulted before, but this incident was different because my attacker wasn’t a stranger lurking in the shadows. He was someone who'd brought me electrolyte water when I came back from Mexico with a stomach bug, who'd cried when sharing moments from his childhood. He was someone I could argue with about whether Bob Marley was a misogynist for expecting his wife to sing back up on songs he’d written for his new, younger lover. When those debates unfolded to reveal my deeper fear—that men, at their core, didn’t really love women—he was protective, dependable, and loving. Until, one night, he wasn’t.

In the aftermath of the attack, only my grief outweighed the betrayal I felt. But like many sexual assault victims, I tried minimizing the emotional impact. Two months, I told myself arbitrarily. Two months and everything will go back to normal. I thought a 60-day stretch would give me plenty of time to pull myself together. But more than that, it permitted me the fantasy that my pain’s expiration date was nearing.

That house of cards came tumbling down exactly two months after the attack, when I found myself explaining to a male masseuse, through sobs, that I didn’t want to be touched by a man. The episode was so jolting that it forced me to get honest with myself about my situation: I spent nights in bed sobbing to the point of exhaustion—once for 10 straight hours. I was drinking every night, usually by myself, to get through the evenings. I had moved out of the apartment my attacker and I shared, but I was irrationally terrified he'd break into my new house. My libido had evaporated and I was grappling with whether I’d be able to have a healthy sexual relationship again. Just acknowledging the question swept me into a gulf of anguish. All around me, #MeToo was affirming the anger of assault victims; while I could relate, I knew that for me, applying anger to a wound would never be curative. I needed help.

Several days later, I ran a Google search for therapists in my area who specialize in sexual trauma, and found an LPC (licensed professional counselor) just 20 minutes away. Each week we sat in leather chairs, sorting through my pain. I wasn’t at fault, she assured me when I recounted some of my closest friends saying things like, 'You should have seen it coming,' and 'Maybe he was just turned on.' My therapist also assured me I wasn’t broken because I longed for the friendship I once shared with my attacker. She told me that it's a particular trauma response common to victims who know their assaulters. It was as if my room had been filled with smoke, and every week, she helped open another window.

#MeToo was affirming the anger of assault victims; for me, applying anger to a wound would never be curative.

In addition to traditional talk therapy, we also tried eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR), a form of psychotherapy created to treat PTSD. Over the course of several months, I’d recall traumatic mental images of the attack while following a light with my eyes, then reframe those images with new, hopeful narratives. As I traced the tail of that weaving green dot in the dark, the beliefs I’d created to process the assault—men don’t love women; they use cruelty and deceit as a means to sex; only women truly see my humanity—unraveled.

These thoughts were bleak. But they were also starting points that my therapist used to help create new storylines. While the green dot darted back and forth, I repeated amended statements to myself: Some men do love women. Some are capable of loving relationships.

Eventually, I started to believe this new narrative somewhat. Three months into therapy, and two months into EMDR, my despair was dissipating, but it wasn’t gone completely. In fact, it had spread from my brain to my body. My trauma was storing itself as muscle memory. Just the thought of attempting sexual intimacy made my heart race with panic.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

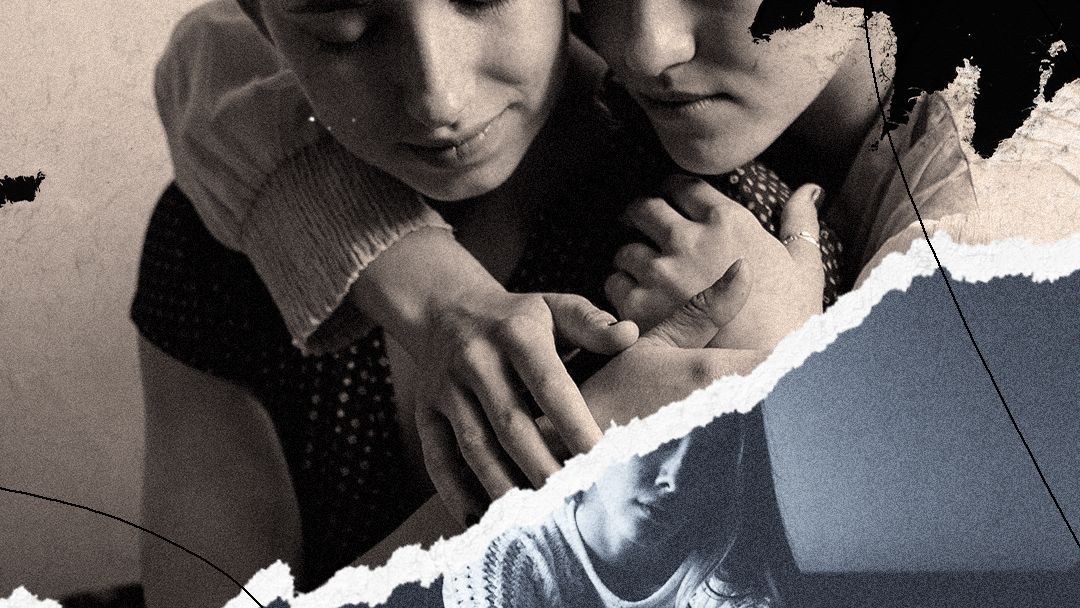

I needed to address the physicality of my trauma. I’d read that cuddle therapy is sometimes used to treat PTSD. I was intimidated by the idea of a one-on-one cuddle session, but I was more afraid to let unhealed trauma dictate my future. So, I went back to Google and found a trained cuddle therapist who specializes in assault rehabilitation. Ultimately, my goal was to be spooned. It was the position I’d been in the night of the attack, and I worried that any future attempt to lie that way with a man would send me into a spiral.

When I arrived to the session, my cuddle therapist led me to a soft futon bed covered in pillows. We’d talked on the phone previously so she could better understand what I was hoping to get from our work. We went slow, starting with breathing exercises. Then hand-holding. About fifteen minutes into the session, we started to cuddle. My apprehension relaxed, my jaw softened, my heart rate slowed. Finally, she moved behind me, pressing her cheek between my shoulder blades. My body shuddered as I sobbed so forcefully, it seemed to release from my gut. I pulled her hand under my chin and curled into a ball. She folded into the backs of my knees.

I left feeling high. Disoriented but relieved—not unencumbered, but lighter. After the assault, it was like my entire body had been surrounded by a prohibitive force field, pushing even the idea of physical affection away. It wasn’t just the fear of assault, it was the fear of opening myself to someone duplicitous, indelicate, grabby. Or worse, someone wonderful, who I trusted, who would leave me the instant I broke down at his touch.

But my cuddle therapist knew why I was there and wasn’t put off by it. She knew why I wanted her to spoon me, knew I was going to cry, and knew exactly what to do when I did. Instead of feeling ashamed, I felt seen and nursed. I saw my cuddle therapist several more times. Every session was uplifting, but I still felt a low-level hum of fear when I thought about sex.

Three months later, I heard about a healer who releases emotional trauma from the body through intentional touch using a therapy called Body Memory Recall. BMR is a form of reiki developed in the West that, like cuddle therapy, hinges on the idea that the body stores, and is capable of releasing, painful memories. In it, a patient is touched very lightly on specific areas of the body in order to release the trauma stored there. Before I could change my mind, I made an appointment for the next day.

In retrospect, I was testing myself. Unlike the other therapists I’d seen, this healer was a man. For the therapy to be successful, I knew I’d have to trust him. Only six months had passed since my meltdown with the male masseuse. Logically, I knew men could love women; EMDR therapy had gotten me there. I just didn’t see proof of it in my own life.

But behind that anxiety was a hope I’d been building through consistent work with my therapists. It was so precious to me that I relied on it fully as I lay face-up on my BMR therapist's table. From the outset, he’d made it clear that I called the shots. Before we started, he asked me to circle all the places I didn’t want to be touched on a body diagram, then walked me through each step of the process so there would be no surprises.

The part of me that insisted I never make myself vulnerable to a man again was the part that most needed to feel safe with one.

I had to remind myself to breathe as he gently pressed his hands along my arms and stomach, operating as a kind of poultice, drawing the grief I’d stored to the surface. He was almost shaman-like, gentle and soft-spoken, never afraid, annoyed, or dismissive of my pain. When he pressed against my sternum, I was weeping, and I moved his hand just below my left breast. He asked what was there for me, but I was crying so hard I barely managed to make out the words: my heart.

Something shifted after that day. Though I approach the mystical with a certain level of earnestness, the actual process of being touched didn’t feel as impactful as the experience of being touched by a man. EMDR therapy taught me that men could love women; BMR showed me what that might feel like. Just the idea of working with a man would have been impossible had it not been for the months of other therapy leading up to that session. I could let go just enough to allow him to access the most fiercely guarded corners of my grief—the part of me that insisted I never make myself vulnerable to a man again was the part that most needed to feel safe with one.

Body memory recall practice was not a silver bullet; my healing process is ongoing, and though I still have to work on healing (with the help of my LPC, who I see weekly), I don’t struggle. When my grief resurfaces, I let it move through me, and just as quickly as it came, it fades. If anxiety arises, I take a deep breath and reorient myself in the present; soon, it dissipates.

I don’t worry about having a sexual relationship with a man anymore; the idea doesn’t flood me with panic or fear. Though I know predators walk among us, I also know that some men can, and do, love women. And after much work, and many tears, I also know that a man can love me, too. Not because therapy “fixed” me or took all my pain away. But because it taught me that it’s safe to show my truth—each aspect of its longing, anguish, joy, and hopefulness—to the right man, the one I choose to trust.

If you, or someone you know, has been a victim of sexual assault or harassment and would like help, visit RAINN.org

Related Stories