The Lost Daughters of Salerno

The news cycle moved on, but the town that became the final resting place for 26 migrant women has not forgotten them.

The photo in The New York Times on November 7, 2017, was heart-stopping: a black body bag suspended in midair against the dawn sky as a crane lowered it from a Spanish rescue ship and a line of silver hearses waited with empty coffins on the pier below. The headline read “26 Young Women From Nigeria Found Dead in Mediterranean Sea.” The 26 women, mostly in their teens, had drowned when the overloaded inflatable dinghy they were traveling on from Africa to Europe capsized. It was one of the key moments in Europe’s four-year migrant crisis—like the viral photos of the two-year-old Syrian boy Alan Kurdi, whose fragile body had washed up on a Turkish beach in 2015—that shocked the world anew about the suffering and danger endured by those fleeing war and economic hardship for better lives elsewhere. “These young women were searching for freedom, and they found death,” says Monsignor Antonio De Luca, a bishop in Salerno, a port city in southern Italy where the women’s bodies were unloaded from the rescue ship and later laid to rest. “It is a tragedy for humankind,” adds Salvatore Malfi, then Salerno’s police prefect.

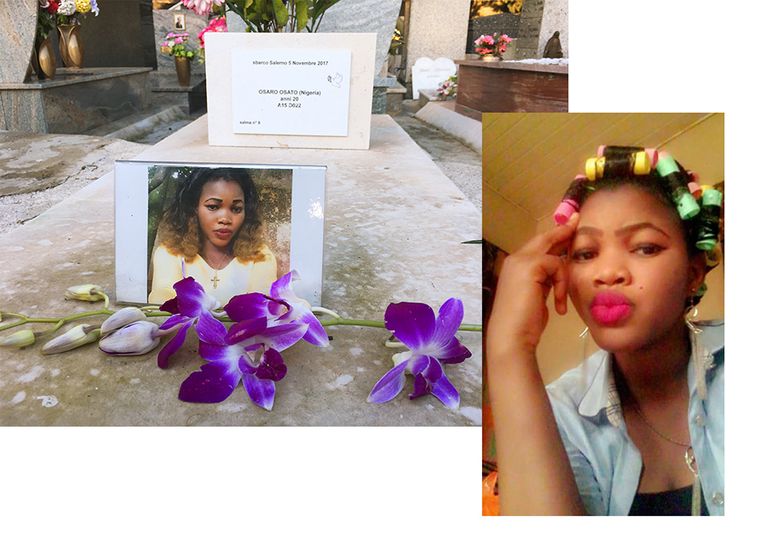

In the 20 months since, Nigerian and Italian authorities have been investigating the accident to determine who was criminally responsible. As the media has moved on, however, the young female victims have been largely forgotten. Only two—Osato Osaro and Marian Shaka, both age 20—were formally identified by surviving relatives. The rest of the women, estimated to be between the ages of 14 and 20, remain nameless and unclaimed. They were found without IDs or cell phones; investigators suspected they had been sex trafficked. They were buried in Salerno with only a six-digit number marking each of their graves and documents placed inside their coffins describing their identifying marks, such as scars, their hairstyles, and the clothes they were wearing when their bodies were recovered from the freezing sea. One teenager, the Italian coroner’s office revealed, had been wearing a T-shirt that read “I am super happy.”

Only two were formally identified by surviving relatives. The rest of the women remain nameless and unclaimed.

So many questions about the women’s lives are unanswered. Where did they come from, and what did they endure? What were they hoping to achieve in Europe? What compelled them to risk their lives? What were their fears, their loves, their deepest wishes? In January, Marie Claire traveled to southern Italy to piece together the last few months of one of the victims, Osato Osaro, and meet some of the survivors from the same fateful boat journey who could shed light on what happened to the 26 figlie di Salerno, or 26 daughters of Salerno, as the town now calls them.

Among them was Osato Osaro, who had always wanted to be a nurse. “It was her dream,” says her younger brother Osazuwa, 18, who survived the sinking of their dinghy and now lives in a refugee center outside Salerno. When they were children growing up in Benin City, the capital of Edo state in southern Nigeria, Osato would practice her nursing skills on him with big-sisterly zeal. “She used to bandage my whole body so tightly that I couldn’t move,” Osazuwa says, smiling at the memory. In April 2017, when Osato was 19, she achieved her goal, completing her nursing diploma at a government hospital. But the cash-strapped hospital laid her off the very same day. A month later, on May 24, Osato set off on a perilous journey to Europe, taking Osazuwa with her. “My sister believed she could get work as a nurse in Italy or Germany,” he says. “She was a very kind person and also strong-willed. She wanted a better future for both of us.”

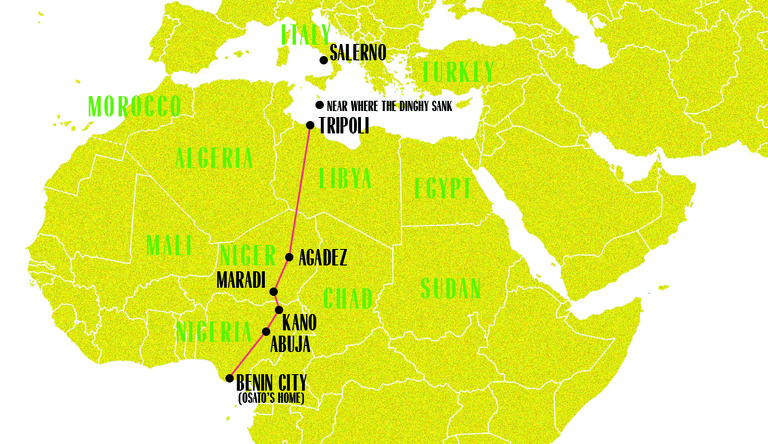

It wasn’t to be. The flimsy rubber boat on which Osato finally made the crossing to Europe, after a 3,541-mile journey overland from Nigeria, was carrying over 130 people, roughly three times its maximum passenger load. It sank fast when bad weather hit off the coast of Libya in the early hours of November 3, 2017. Osato’s lifeless body was fished out of the waves, along with those of the 25 other women, by a Spanish naval ship named Cantabria. Osazuwa and 63 others survived. An estimated 50 more from the same dinghy, including children, died in the water, and their bodies were swept away. The Cantabria transported the 26 drowned girls and the survivors to Salerno, the nearest available European port.

It was almost dawn two days later when the Cantabria arrived. The sky and sea were a matching shade of gunmetal gray. Warned in advance about the ship’s tragic cargo, about 100 Italian medics, emergency workers, journalists, and local officials were waiting on shore in Salerno, 30 miles southeast of Naples. “Usually when a ship carrying rescued migrants comes into port, there is a lot of activity and shouts of joy from the survivors,” says Monica Di Mauro, a reporter with TV-OGGI Salerno, a local TV station, who was there that Sunday. “This time there was only silence. Total silence. Shock and sadness hung over the whole port. The hairs on the back of my neck still stand up when I remember it.”

"My sister was a very kind person and also strong-willed. She wanted a better future for both of us." —Osazuwa

Since the migrant crisis began around 2015, driven by war, extreme poverty, and the opening of new routes for smuggling people across Africa and the Middle East, deaths among those trying to reach Europe by sea have grown appallingly frequent. Some 1.7 million illegal migrants have arrived in Europe by sea over the past four years. Almost 18,000 have died along the way, according to the U.N.’s International Organization for Migration (IOM), including 3,139 in 2017 and 2,299 in 2018.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Osato was told the journey would take “no more than three to four weeks,” says Osazuwa, a skinny 18-year-old wearing jeans and a yellow polo shirt. The trip ended up taking a grueling six months. Migrants coming from Africa routinely endure severe hunger and dehydration, beatings, extortion, rape, imprisonment, and forced prostitution at the hands of vast illegal networks of traffickers, armed groups, and brothel owners along the routes. “Our lives were at risk many times,” he says.

The arrival in Salerno of so many young women who had suffered terrifying deaths “brought home—literally” the horror of the migrants’ plight, says Di Mauro. As a small port that functions as a tourist gateway to the glamorous Amalfi coast, Salerno had experienced far fewer migrant arrivals than many other areas of southern Italy had. The solemn atmosphere remained as the 26 bodies were unloaded from the ship before anyone else was allowed to disembark. “The crew used a crane to lower them off the deck,” Di Mauro says. “The body bags kept coming, one after another, for what seemed like forever. It was a sight I will never forget.”

Osato’s grave in Italy, 2017 (left); an undated photo of her in happier times in Nigeria, where she dreamed of becoming a nurse.

The unloading took two hours. After the young women were taken to the morgue, the real mystery began. Survivors confirmed that the boat had left from the Libyan area of Warshefana, just outside the capital, Tripoli, and all the girls were Nigerian. Osato’s body was identified by Osazuwa. One other victim, Marian Shaka, was identified by her 29-year-old husband, Sule, who was on board. Many were dressed in jeans and T-shirts and had manicured nails. Due to the women’s lack of ID or personal effects, which traffickers usually confiscate, the Italian prosecutor’s office suspected they had fallen prey to the sex trade and opened an investigation into the deaths. (At press time, the investigation is ongoing.)

In a 2017 report, IOM estimated that 80 percent of Nigerian women arriving by sea were “likely victims of sexual exploitation” both during their voyages to Europe and after arriving. IOM confirmed 6,599 female Nigerian victims of sex trafficking in Italy in 2016. It also noted an alarming rise in the number of trafficked adolescent Nigerian girls arriving by sea, up from 107 in 2013 to 3,040 in 2016. Highly organized gangs, the report says, have begun targeting younger women due to growing awareness among adults about the dangers of being tricked.

After Osato lost her job, Osazuwa says, she was approached by a woman in Benin City who promised her work as a nurse in Europe. “Osato said it was a great opportunity and convinced me to go with her so I could finish my education,” Osazuwa says. “I hoped to be an engineer.” Jobs and spots at colleges for young people in Nigeria, where 62 percent of the population is under 24 years old, are in desperately short supply. The unemployment rate, currently at 23 percent, has risen for the past 12 quarters straight, and less than half of high school graduates who apply to university are accepted. Adding to the country’s woes is the havoc wreaked by extremist Islamist rebel group Boko Haram, responsible for kidnapping about 270 schoolgirls in the Chibok region in 2014.

Surviving migrants wait to disembark the Spanish ship that rescued them from the Mediterranean Sea, 2017.

Osato’s home state of Edo has for years been the country’s main hub of human trafficking. Powerful Nigerian crime syndicates exploit the area’s extreme poverty and lack of opportunities to lure away young people with false offers of well-paid jobs in faraway lands. “The agents who first approach potential victims are often kindly, maternal women,” says Julie Okah-Donli, director-general of Nigeria’s National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP). “Sometimes they are relatives or close friends of the family.” Osazuwa says his sister didn’t know the woman who approached her but believed she was trustworthy. “Osato was very proud of being a nurse,” he says. “The lady comforted her when she was upset about losing her job and said she could help.”

For many of her teenage years, Osato had been the primary caretaker for Osazuwa and their two younger brothers, who are now 11 and 15. Their mother was in poor health, and their father “wasn’t around much.” The family lived in a three-bedroom brick house on the outskirts of Benin City. “Osato used to help me with my math homework and cheer me up when I was sad. We played games and laughed together a lot,” he says. “We didn’t have many things, but we always had enough food and clothes. Osato used to cook fried rice for our dinner.” A devout Christian, she went to church on Sundays and spent her free time studying. She didn’t go on dates or have a boyfriend, adds Osazuwa. “She didn’t have time for that.”

At nightfall on May 24, 2017, they boarded a minibus with about 20 other men and women, mostly under the age of 25, who were also headed for what they hoped would be a better future in Europe.

The desire to provide for her younger brothers was a huge motivating factor for the risky trip to Europe. Osato sold some of her belongings, including the family’s TV and her hair dryer. (One of the first things Osazuwa mentions about her is that “she liked styling her hair.”) Together with her savings, she managed to raise a $1,400 deposit for her and Osazuwa to travel. “The lady told her that the journey would cost more—we never knew how much—but that we could pay it back after we were settled in Europe,” he says. As instructed by the agent, the pair left home with only a bag each containing a couple changes of clothing, toiletries, and a little leftover cash to buy food. At nightfall on May 24, 2017, they boarded a minibus with about 20 other men and women, mostly under the age of 25, who were also headed for what they hoped would be a better future in Europe. “The mood was good at first,” says Osazuwa, who was just 16 at the time. “Everyone was excited and talking loudly.”

They drove through the night to Nigeria’s capital, Abuja, where they were transferred to a different minibus. From there, they went on to the city of Kano, near the border with Niger, where an unknown man issued them fake passports that featured headshots, which they had given to the agent back in Benin City. The group had to stop a few times at military checkpoints where the minibus was searched, but they had no problem with the soldiers; traffickers are known to pay them off. After dark, 48 hours after they’d set off, they were put into motorcycle taxis in pairs and driven into Niger. Again, there was no problem with border guards. Osato was delighted. “Every time we got through a checkpoint, she’d clap and say everything was going to be fine,” Osazuwa says.

The ease up to that point was deceptive. The next destination was Agadez, Niger, the last pit stop before the arduous journey across the vast Sahara desert to Libya. At 3.6 million square miles, the Sahara is a lawless, sand-covered wilderness roughly the size of the entire United States. Traveling through it is fatal for many. IOM estimates that for every migrant who dies in the Mediterranean Sea, there are at least two who die crossing the Sahara. Osato and her brother were about to face its dangers. First, however, their group was left for 10 days in an abandoned shed outside Agadez with little food or water, waiting for their next ride.

Already physically weak, the group was eventually piled into two open pickup trucks driven by armed men. They were told not to talk to one another and warned they’d be beaten or shot if they failed to obey. If they fell out of the vehicle, the drivers said, they’d be left behind. The pickups went at top speed. “We had to cover our heads with T-shirts to try to stop the sand from getting in our eyes, nose, and mouth, but it didn’t help much,” says Osazuwa. When the group stopped for toilet breaks, they saw injured migrants and decomposing bodies lying in the desert. At checkpoints, guards demanded $10 bribes from each migrant; those who couldn’t pay were beaten with plastic pipes. Osato started to panic because the bribes were using up what little money she had left for food and water. They’d heard stories on the road that some migrants had to resort to drinking their own urine mixed with cocoa powder to stay alive.

The closer to Libya they came, the worse things got. At night they stopped at desert camps for shelter. The traffickers would choose female migrants and take them away to their tents by force. “They beat up very violently anyone who would not go freely,” Osazuwa says. “One girl had her arm broken.” When asked whether Osato was among the women taken, Osazuwa says he prefers not to answer. The desert journey lasted nine days. Once in Libya, they passed through various cities in the south and center before being taken to Tripoli. “We thought we’d be taken straight to the boat,” Osazuwa says, “but instead we were put in a ghetto with hundreds and hundreds of other people from Nigeria and other African countries.” The so-called ghettoes are usually old warehouses or other large abandoned buildings that traffickers have turned into cramped living quarters for migrants. Most are told at this point that the money they have paid so far does not include the sea crossing and that they must work to pay for their passage.

The route Osato took from Nigeria to Italy, according to her brother Osazuwa.

Europe’s law-enforcement agency, Europol, estimated in a 2017 report that the trade in illegal migrants crossing the Mediterranean via sub-Saharan Africa is worth between $4 billion and $6 billion per year. The business took off after the 2011 toppling of Libya’s longtime dictator, Muammar Gaddafi, during the Arab Spring. Following his demise, the country fractured into civil war between rival governments, ethnic militias, and various armed gangs. The chaos enabled traffickers to open routes through the country, with everyone along the way taking their cut, including local agents, corrupt police and border guards, local mafia, owners of safe houses and ghettoes, and brothel madams. Migrant-smuggling groups that started out as loose networks have consolidated into profit-driven, exploitative criminal enterprises with true transnational reach, Europol reported.

For the first two weeks in the Tripoli ghetto, Osato and Osazuwa were allowed to stay together. But one morning Osazuwa was dragged out at gunpoint and driven outside the city with a truckload of other male migrants. “I was sure I was going to be killed,” he says. “Instead they put us to work in some fields. We had to work from morning until night without any pay and almost no food.” He found a chance to run away after two months but was captured by another armed group on his way back to Tripoli and thrown into a detention center—makeshift jails for unruly migrants where torture and beatings are the norm. “The guards whipped me, and I saw many men who had been shot in their arms and legs.” He was released after another two months and was relieved to find Osato still at the original ghetto. His sister, however, was no longer her usual upbeat self. “She was very upset and scared and didn’t want to talk.”

Looking back, Osazuwa realizes now that his sister was protecting him from what she had almost certainly endured. “She didn’t tell me what she had been doing or how much money we had to pay to catch the boat, but I know it was a lot, like, thousands of dollars,” he says. The testimonies of countless young African women interviewed by the IOM and the U.N. Refugee Agency confirm they are almost always forced into sex work in Libya or, less often, domestic slavery to pay off arbitrary “debts” traffickers claim they owe. Sums range from $8,000 to $35,000, and extra is added for food and lodgings. Osazuwa finally understood what Osato had likely experienced after an autopsy revealed she was almost three months pregnant.

A female survivor who was on the same boat, Favour Ezechi, 27, has little doubt that Osato’s pregnancy was the result of rape or forced prostitution. “In the ghettoes, you are not allowed to have relationships with other migrants or to even speak to each other. The punishment is severe.” Ezechi was trafficked to Libya in 2011 and was trapped there for over six years. She was a junior hairstylist in her home state of Abia, in southeastern Nigeria, when a client told her she could get highly paid work in a salon on the European island of Malta. “This lady was very well dressed and drove a beautiful car, so I believed her,” Ezechi says. She journeyed through the desert like Osato, but her group was sold multiple times to different militia groups.

Sometimes we had to sleep with 20 or 30 men a day, whenever clients turned up.” —Favour Ezechi

When she reached Libya, she was sold to a brothel madam, who told her she must pay back $12,000 by working as a prostitute before she could leave. “There was no time off or set working hours,” says Ezechi, who lives in a reception center in southern Italy while she waits to receive official refugee status. “Sometimes we had to sleep with 20 or 30 men a day, whenever clients turned up.” In the case of Nigerian women, one of the ways in which they are coerced into cooperating is by taking a juju oath—potent black magic whereby their hair and nail clippings are used in a spell binding them to honor their debts. “Breaking the oath means something terrible will happen to you or your family,” Ezechi says. Belief in such traditional magic is widespread, particularly in rural areas. “Many girls didn’t try to escape because they were afraid of juju,” she adds.

Before Ezechi could finish paying off her debts herself, they were repaid by a wealthy Nigerian client based in Tripoli who invited her to move in with him. To escape the brothel, she accepted his offer, then bore him three children in quick succession. Over the six years she spent in Libya, every Nigerian migrant woman she met had been raped or forced into sex work “almost without exception,” she says. “It was as if men thought the only reason Nigerian girls existed was for sex.” Ezechi’s male benefactor turned out to be a violent abuser. She secretly saved cash so she could make the crossing to Europe with her children.

Ezechi doesn’t recall meeting Osato or Osazuwa on November 2, 2017, although they were all herded onto the beach together outside Tripoli to await their boat. “There were about 400 people there to catch three boats at the same time,” Ezechi says. “It was very chaotic.” More than 130 people were loaded onto each inflatable dinghy, women and children in the center and men around the rim. Osato and Osazuwa were separated by gender on the same boat and had no time for parting words. “We just locked eyes for a brief second,” says Osazuwa. “Osato looked very afraid.”

The boats left at 11 p.m., leaving at night to minimize the risk of detection by the Libyan Coast Guard, and soon lost sight of one another. Osazuwa says their boat hit turbulent weather after three hours, when they were in international waters. “Big waves came over the side, and the boat started filling up with water,” he says. “Everyone started screaming.” Osazuwa shouted for Osato but couldn’t see where she was because it was pitch-black. The next thing he knew, he was in the cold water fighting to stay alive—he was not a strong swimmer—and there was no sign of his sister. He knew she could not swim at all.

Although there is less risk of women and children falling out of a dinghy during the crossing when they are huddled in the middle, it is by far the most dangerous place to sit if the boat hits trouble. “When these cheap inflatable boats start to fill with water, they quickly collapse in on themselves, closing up like a clam shell,” explains Giuseppe La Mura, a Red Cross rescue worker in Salerno. “Men can jump off, but women and children get trapped under the water, and they are always the first to die.” This appears to be what happened to Osato and the 25 other young women, says La Mura, who was at Salerno’s port when the Cantabria delivered their bodies. The unspeakable tragedy of that night didn’t end there. Along with another 50 or so people who were swept away, all three of Ezechi’s children—daughters Joy, six, and Adanna, four, and son Goodness, two—drowned in the waves, and their bodies were not recovered. Ezechi says she has no memory whatsoever of how she survived, in her agonizing panic and grief, in the water for five hours before rescuers arrived.

After interviewing survivors, Italian prosecutors determined that the traffickers responsible for sending the migrants to their deaths on an overloaded boat were not among them. In many cases, to avoid capture, traffickers do not pilot the boats themselves; they enlist inexperienced migrants instead, offering them cheaper fares to be at the helm. Federico Soda, IOM Italy’s chief of mission, says there is no question such reckless disregard for life is tantamount to murder. “These people should be punished with the full force of the law,” Soda says, “but it is extremely difficult to catch them if they are outside Europe.” While the prosecutor’s office in Salerno has not yet released its findings, a local Italian journalist speaking anonymously said it is likely to implicate some “very senior people” among the wealthy elites of Libya and Nigeria, including government figures and top army generals. “These trafficking rings go right to the very top,” he says.

There are some government attempts to stop the harmful trade. Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency NAPTIP, established in 2003, “vigorously pursues” traffickers and criminal gangs on its own soil, says Julie Okah-Donli. It also runs awareness campaigns at schools and town halls to warn young people not to be duped. “I think the message is getting through, but we also need to greatly improve opportunities for young people here so they are not tempted to leave,” she says. Niger passed its first anti-trafficking law in 2015 and has stepped up efforts to enforce it in the Sahara over the past year, which has slowed the trade, says the IOM.

We truly think of these girls as daughters of Salerno.” —Concita De Luca, TV reporter

Meanwhile, Nigerian arrivals in Italy dropped in the past year, after the country’s new far-right government closed its ports to rescue boats. However, in the endless game of geopolitics that has characterized Europe’s migrant crisis since the beginning, African migrants have now started heading for Spain in large numbers. “We are still trying to find a cohesive strategy to deal with this issue,” Soda says. “Closing ports does not help. We need Europe-wide policies that meet the needs of migrants and tackle trafficking head on.”

Given the overwhelming task of coping with the flow of migrants who make it to Europe alive, the problem of identifying the dead and missing is often overlooked. Soda estimates “only 2 to 3 percent” of bodies retrieved after accidents in the Mediterranean are ever properly identified. “Unless they have their ID documents on them, there is no way of knowing who they are or how to contact their relatives.” The Italian authorities, in cooperation with NAPTIP in Nigeria, say they will continue trying to identify the remaining 24 young women who drowned. Their mass funeral took place in Salerno on November 17, 2017, two weeks after their dinghy sank. It was attended by an Italian bishop and a Muslim imam, members of the local Nigerian community, and various Italian officials and sympathizers.

Paying memorial to those who died.

Some female journalists in Salerno, however, refused to leave it there. TV reporter Monica Di Mauro and her colleague Concita De Luca organized a memorial to make sure the women’s lives won’t be forgotten. “The whole city was very affected by this tragedy,” says De Luca, a reporter for local Catholic TV channel Tele-Diocesi. “We truly think of these girls as daughters of Salerno.” The women enlisted 26 female journalists to write passages imagining the lives of each of the deceased girls and to read them at a ceremony on March 8, 2018, International Women’s Day. “We wanted to become them, to express their hopes and dreams, their voices, so they somehow stayed alive through us,” Di Mauro says. “We didn’t want this kind of disaster to become normalized.”

In Salerno’s main cemetery, where 14 of the women are buried (12 other graves are in various cemeteries around Salerno), a glistening metal statue of a tree titled 26 Broken Branches now stands near the entrance. Osazuwa visits the cemetery as often as he can to tend to Osato’s grave. He keeps fresh flowers there and has positioned a framed photo of her—one “that she would approve of”—wearing a pretty yellow dress and a gold cross necklace. Their mother died one year ago without knowing about Osato’s fate, and Osazuwa likes to imagine they are together. Under the graveyard’s leafy trees, he sits and talks to Osato about his new life in Italy, where he is already almost fluent in the language. He is hoping to get his residency papers soon so he can try to bring his two brothers to live with him. “I think,” he says, “my sister would have liked it here.”

This story originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of Marie Claire.

READ OUR SERIES ON WOMEN & MIGRATION