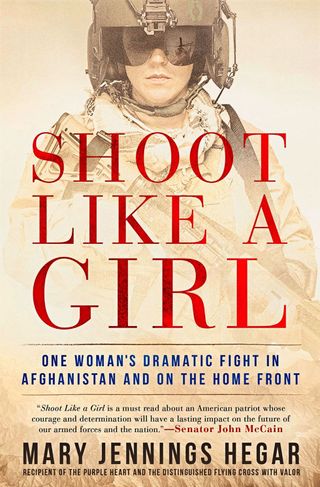

I Fought the Taliban from the Sky

As a U.S. Air Force helicopter pilot, Captain Mary Jennings Hegar was tasked with rescuing injured soldiers. On one such mission in Kandahar Province, Afghanistan, she and her crew suddenly found themselves battling enemy fire while trying to make their daring airborne escape.

On July 29, 2009, military helicopter pilot Mary Jennings Hegar was on her third tour in Afghanistan when, during a medevac mission, she found herself under attack in enemy territory. In this exclusive excerpt from her forthcoming memoir, she tells her story for the first time.

As copilot of our Pave Hawk, Pedro 15, I was checking the radios and aligning the navigation system with the GPS satellites on the taxiway at Kandahar Airfield in Afghanistan. Then I saw our pilot, George, and the team jogging toward me on the hot tarmac. When George reached the aircraft, he flung a piece of paper across the seat. The mission sheet said we were on our way to rescue three critically injured American soldiers whose convoy had hit an IED (improvised explosive device) complex ambush 25 minutes out from Kandahar. Steve, our flight engineer, and our gunner, TJ, jumped in the back and put on their helmets before three PJs (pararescue jumpers) climbed on board, with all their gear laced into the webbing of their body armor, and assault rifles pinned to their chests. The PJs are the most unsung heroes of war. Besides making the medical decisions, they take charge in the unlikely event that we end up in ground combat.

After we flew north over the hills, the landscape started to turn green—a seemingly pretty change from the dusty dry brown that surrounds the base and most of central Kandahar. Behind us was our sister ship, Pedro 16, which, like us, carried a handful of PJs and a crew of four. If one helicopter were to go down, the other should be able to rescue the second crew and the patients. Pedro 15 was lead ship, meaning Pedro 16 would cover us with its door guns while we got the wounded out.

Hegar is sworn in to the National Guard by Captain Graham Buschor, 2005

The radio traffic from two Army choppers supporting the hobbled convoy from the air was reporting that the firefight we were heading into was over, at least for the moment. The Army choppers were OH-58s, Kiowa Warriors—nimble two-pilot helicopters with a giant bug's eye of a surveillance camera sitting on top of the rotors, and rocket launchers above one skid (landing gear) and a large-caliber machine gun over the other. It sounded like the Kiowas had pushed back the Taliban enough that we could grab the wounded without taking too much fire.

I got on the radio to Shamus 34, one of the Kiowas: "Shamus three four, Pedro copies."

There was silence. Our sister ship broke through the static: "Pedro one five, did you catch that? Shamus three four reported they have suppressed the threat to the convoy for now, but there may still be enemy forces to the south."

I was confused, but very quickly it dawned on us: No one had heard our reply. Our own radio jammers, put in place to scramble the enemy's communication efforts, sometimes left our aircraft deaf and dumb. Now we'd have to relay all our communication through our sister ship. And when you're flying into hot enemy territory, it's not really the best time to play "telephone."

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Before I could worry much about the radios, the broken-down convoy appeared in the valley below us. The line of drab U.S. Army trucks looked like a toy train, blocked in by a scorched crater. Taliban gunmen hiding in the village to the south had the whole squad pinned down.

"Pedro one six. One five in the blind. We're coming right two seven zero landing north of the convoy," reported George, telling our sister ship we would be doing a right turn all the way around to face west.

George didn't know if our sister ship could hear him, but going "in the blind" meant that he would continue to transmit just in case Pedro 16 could. He was going to swing around in a horseshoe pattern and land to the right of the convoy, putting the reported enemy activity to the south, out our left door. That way, the armored trucks between us and the enemy guns would provide cover for the PJs and the wounded while we loaded up the helicopter. We'd drop in so two of the three PJs could jump off. Then we'd head back above the ridgeline, allowing the PJs to work on the wounded without having to scream over our rotor wash. When they were ready, they'd call the third PJ, still on board our aircraft, on their inter-team radio to bring us back.

An OH-58 Kiowa helicopter

Just 40 feet before impact, George suddenly pulled the nose up, flying alongside the convoy, rotors pitched back like a falcon pumping its wings to land in a treetop. The PJs jumped out and ran toward the convoy.

Then I heard a crack like a baseball bat hitting a home run, and our windshield shattered right in front of my eyes. My arm felt warm and wet, but I was thinking only about the wrecked windshield. Our maintainers had spent hours replacing it the day before. All their work was ruined now. One look at George's horrified face reeled me back to the present. His lips moved, and the whole crew was shouting at me over the intercom, but for an instant all I could hear was the high whine of the engine and the deep comforting thunder of the rotor blades. I followed George's gaze to the blood spreading over my exposed arm and the leg of my flight suit. I had the strangest split-second moment of relief that I had tied my sleeves around my waist in an attempt not to overheat. Now I wouldn't have to patch a bullet hole in the arm of my uniform.

"I'm hit, but ... I can still fly," I told them.

"Are you really OK?" There were four voices shouting all at once in my headset. George pulled the helicopter up in the air and out of rifle range as the PJ team lead squeezed over the console to look at my injuries. Shrapnel peppered my right forearm and right thigh. The arm wounds were superficial. I couldn't see the leg wound, but the bloodstain grew from the size of a grapefruit to the size of a basketball. After a few minutes, the stain stopped spreading, and I began to breathe easier. I'd never been shot before, but I'd flown so many injured troops that I could tell a serious wound from a paper cut. No reason to call off the mission.

"I'm hit, but...I can still fly," I told them.

In the back, TJ was doing just that. "I repeat...Pedro one five copilot hit...We're RTB..." Return to base!

"Gunner—hold that," I said. They were all looking at me in disbelief. "Look, guys, I swear!" I reached my arm up over my head and moved it side to side. "I have full range of motion, and my leg has already stopped bleeding. We've got three cat-A soldiers down there. Let's get back to it."

Category A meant urgent, and I wasn't going to be the reason the soldiers on the ground bled out. George began to turn the aircraft back toward the convoy. Steve broke in, telling us to enable the contingency power switch, which would give us extra power if we needed it but is used only in dire circumstances, as it can burn up your engines if you're not careful. I flipped it on.

Right on time, one of our PJs on the ground broke in over the radio: "Pedro one five, Guardian's ready for pickup."

Then the headset crackled: "Pedro one five, one six...bent gun."

Shit, our sister ship was telling us it had a broken gun and would be able to support us out of only one side of the bird. The only thing worse than returning to the scene where you got shot is doing it when your support ship can't fire one of its guns to defend you.

"Roger. Grinder." George, cool as a cucumber, was calling for the two ships to switch roles. Protocol states that if your support ship is impaired, you become the support ship.

"Negative. We don't have the power," came the reply from command in Pedro 16, fast and a little frantic. "We're too heavy. We can't do it."

Fighting California wildfires, 2008

George and I exchanged a silent glance. It was true that it was a lot of extra weight to ask Pedro 16 to lift with three patients, our two PJs, plus their own full crew, but there are always fixes to unforeseen problems. The easiest solution was for them to dump some fuel, then reroute after the pickup to a nearby refueling point. He's lost his nerve, I thought to myself. George nodded like he could read my mind. All of us who had done tours in Afghanistan had seen someone lose their courage. There was no coming back from that. Now we'd have to stay lead. At least the Kiowa Warriors had hung around. Their pods were about half full of rockets, which would give us some extra cover.

As our wheels touched down, heavy slugs from enemy machine guns began to hit us hard, beating out a steady rhythm into our eight-ton aircraft, now rocking like a little rowboat on the ocean. I could feel more than hear the big rounds slamming into us. They shook my insides. The row of armored trucks gave us little protection from the barrage.

It was clear that the enemy had been planning this attack in the hopes of taking down a rescue helicopter. Insurgents were dug into the high ground with weapons aimed at the landing site. They had concealed their position to the extent that our cover ships could not determine a point of origin for the fire we were taking. We were on our own. TJ couldn't spot the enemy machine gun, either, and he could hardly open fire while our patients were being loaded in. Not to mention, his gun was designed to fire down, not up.

Once the wounded soldiers were loaded, I gave George the thumbs-up. We barely had enough power to clear the terrain ahead of us, but thanks to Steve, we had engaged our contingency power switch on the way in. He had known that when we went back in, we'd be facing a firefight. That decision was saving our lives.

Seconds after takeoff, Steve said something that turned my blood cold: "We've got fuel back here... " From the smell, I knew he meant that it was spewing into the cabin. The two gas tanks in a Pave Hawk are heavily armored, so the Taliban's machine-gun rounds must have hit the tiny fuel line. Each tank fed one of the jet engines, so now one of them was running on fumes. With our load, one engine wouldn't be able to keep us aloft. I instinctively threw the fuel selector into cross-feed, buying us a few minutes as the left engine started receiving fuel from the right tank. The needle for the right tank, now feeding both engines, was moving toward empty far too quickly. There was only one option left.

"We need to land."

"We're RTB," George replied. He didn't know about the empty tanks.

"We're not going to make it back to Kandahar," I stated. "We're pissing gas. We have to land, or we're going to crash."

He immediately pointed out a rocky spot where he planned to drop the helicopter. It was the right call. Harder to put land mines under rocks than sand. An eerie hush came over us as he dove toward the rocky terrain. Everyone did his or her part to prepare, but very soon there was nothing left to do except hold on tight.

"The pain wouldn't slow me down, certainly not today. The only thing to worry about now was figuring out how to get the hell out of there."

We were without hydraulic assistance to the controls as George guided us down—I could feel the strain through my seat, like driving an 18-wheeler with no power steering. As we touched down, far faster than usual, we could hear the crunch on impact. I felt a jarring crack in the middle of my back, but the pain wouldn't slow me down, certainly not today. The only thing to worry about now was figuring out how to get the hell out of there.

It was our new reality: IEDs on the ground everywhere, no perimeter security, hills around us full of Taliban. I knew I'd fight to the death—far better that than being captured and marched through enemy territory with a bag over my head. I grabbed my rifle and slid down to the rock-strewn terrain. After three tours in Afghanistan flying into countless combat zones, this was the first time I'd ever stepped outside the wire of an air base, on the ground in enemy territory. It was a dangerous place to be—circled around a fuel-soaked, flightless bird, as TJ transmit- ted our location over an emergency radio channel. "Mayday. Mayday ... Pedro one five exfiltration."

Our sister ship showed no signs of being willing to land. The whole point of traveling in twos is so that one ship can rescue the other in an emergency situation. Pedro 16 had already declined to get our patients owing to fears about weight; now we were asking them to lift even more.

The crews of Pedro 15 and Pedro 16, 2009

Then the shooting started in earnest. Taliban fighters had zeroed in, and bullets were zipping across the rocks around us. Despite the shots coming from all different directions, no one on our team had fired a weapon yet. Our rules of engagement said we needed positive identifica- tion. In this case, the rules made perfect sense. We might have let off some frustration firing wildly at the hills, only to waste ammunition we sorely needed to save for when the Taliban came for us in person. Without a clear point of origin for the enemy gunfire, there was no use in pulling the trigger, and we couldn't risk endangering possible civilians. The helicopters overhead couldn't see, either—there were too many crags and caves up the hillside giving our enemy great cover.

Just then, the radio crackled on the emergency channel. "Pedro one five, Shamus three four." It was one of the Army Kiowas. "Be advised we're RTB for refuel and rearm."

Goddamn it—they're leaving us, too? Without air cover, the Taliban would overrun our little team within minutes. The Kiowa's rockets were the only thing keeping the enemy at bay. The Kiowa pilot had to know that, because what he said next was crazy: "If you can move your asses—fast—we'll swing by you first and take you out on our skids."

This was Afghanistan, not Hollywood. Kiowas do not land on the battlefield, and they do not carry pilots on their skids. Kiowas don't have extra seats, and they don't have enough power to handle the extra weight of passengers, especially not in extreme heat.

"Negative—there's too many of us—and we've got three patients."

"Copy that, Pedro one five," the Kiowa pilot said. "We'll have Pedro one six land to get your patients and PJs."

Finally. The Kiowas would take four aircrew out on their skids first, and the rest would go with Pedro 16. This might just work.

"Aircrew out first," we heard. "MJ—you and the gunner jump on the first Kiowa."

As much as I hated to leave my team behind, the sight of those two elegant Army choppers fluttering down to get us made me swoon. It was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. I turned to a PJ lead and started stripping ammo magazines and water out of my survival vest. He needed it now more than I did. I kept one magazine in case we had to make another unscheduled "landing." The other PJ clipped a lanyard into my belt with a carabiner so I could latch myself to the Kiowa's skid.

Despite my wounds, I wasn't feeling any pain, just adrenaline cours- ing through my body. TJ and I hunched under the spinning rotor blades and headed for opposite skids to keep the bird balanced.

I looped my lanyard around the rocket pod mount, clipped it back into my belt, and slapped the fuselage twice to say go, but the pilot was already beginning to lift the aircraft. Even a fearless chopper pilot like him didn't want to stay more than a moment down here. I heard the difference in the rotors as the Kiowa struggled under the extra weight of two passengers it wasn't designed to carry.

Then all of my Christmases came at once. A tiny flame of light caught my attention from about 70 yards behind the crashed aircraft. Looking down the sight of my rifle, braced across the rocket pod, I watched a Taliban fighter's muzzle flash, then flash again.

Point of origin! I finally had something to shoot at and managed to squeeze off a dozen rounds as we lifted off. I doubted my shots could be lethal or even accurate at this range. All I could hope for was to get the enemy to duck to give us enough time to take off. If I kicked up enough dust, there was a chance the others might be able to see where my shots were aimed so they could identify a point of origin for their own weap- ons. Then I had a thought that chilled me to the bone. The fact that I could finally see muzzle flashes might mean the Taliban, emboldened by the exfiltration attempt, had abandoned their dug-in position to move in and finish off the rest of our rescue team on the ground.

Twenty minutes later, which felt like hours, the Kiowa dropped us off at a forward operating base called Frontenac. I had only one thing on my mind: the fate of those I'd left behind. Before the skids even touched the runway, I unhooked and jumped off. I marched from the landing zone onto the base, barely registering the horrified looks of the other soldiers milling around. I must have been a sight in my fuel-soaked body armor, blood crusted along my arm and down my leg, rifle at the ready, helmet still on. A soldier stepped into my path.

"I had only one thing on my mind: the fate of those I'd left behind."

"Move! I've got to get to the TOC," I demanded. I was aiming for the tactical operations center, where satellite feeds and radios would tell me if our team had survived.

"Captain...Captain, sir, I have to check out these wounds. I can't let you go until I take a look," the medic insisted.

I ignored the "sir" and kept walking, but he continued to shuffle backward in front of me and TJ. Without breaking stride, I switched my rifle to my left hand and showed him my right arm.

"See? I'm fine. Little shrapnel, but it's small, and I can get it out later."

"OK," he persisted, "but I'm going to have to take a look at that leg."

Exasperated, I stopped. If the medic was going to get in my way, he'd better make it quick. I dropped my pants right there in the middle of the yard. A dozen or so soldiers had been watching, but until that moment, I'm not sure they noticed I was a woman under all of that body armor and helmet. Now they stared openly—at my Hello Kitty panties.

TJ stepped up to the nearest soldier and nearly blew him down, "What the FUCK are YOU looking at?"

All of the men snapped out of their stasis and urgently rediscovered whatever activities they had been doing. The medic dropped to his knees, seizing his chance to look at my leg wound.

"OK—no more bleeding. You're good to go ... ma'am."

I reached the plywood door to the TOC and threw it open.

"How can we help you, ma'am?" said the soldier closest to the door. "I'm Pedro one five, and I need to know the status of my patients and remaining crew."

The door squealed again as George walked in behind us. He'd arrived on the other Kiowa skid and looked as anxious as I felt.

"Hey, did Steve and our PJs get out OK?" George asked.

A captain whose uniform looked a little too clean stood up from behind his plywood desk.

"Everyone," he said, "made it."

Editor's note: By shooting at the enemy from the Kiowa's skid, Hegar allowed the helicopter and its crew and passengers to escape. Her actions earned her the Distinguished Flying Cross with Valor Device, making her only the second woman in history to receive the medal, and the Purple Heart. In 2012, she sued the Department of Defense, asserting that the combat exclusion policy banning women from serving in combat was unconstitutional; in 2013, then Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta lifted the ban. In 2016, the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines opened up more than 200,000 combat-related positions to women.

From Shoot Like a Girl: One Woman's Dramatic Fight in Afghanistan and on the Home Front, by Mary Jennings Hegar, to be published on March 7, 2017, by New American Library, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2017 by Mary Jennings Hegar. This excerpt was published in the March 2017 issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now.

-

Olivia Rodrigo Finds the Perfect Spring Dresses at Reformation

Olivia Rodrigo Finds the Perfect Spring Dresses at ReformationShe's worn the brand twice in the past week.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Curiously, Just as Meghan Markle Sends Samples of Her New Strawberry Jam Out, the Buckingham Palace Shop Starts Promoting Its Own Strawberry Jam on Social Media

Curiously, Just as Meghan Markle Sends Samples of Her New Strawberry Jam Out, the Buckingham Palace Shop Starts Promoting Its Own Strawberry Jam on Social MediaThe clip promoting the Buckingham Palace Shop’s product—we cannot make this up—is set to Mozart’s “Dissonance Quartet.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Zendaya's Latest 'Challengers' Serve Is Nearly a Century Old

Zendaya's Latest 'Challengers' Serve Is Nearly a Century OldThe 1930s-era dress may have been pulled months ago.

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

Black Lives Matter Quotes That Are Powerful, Informative, and Necessary

Black Lives Matter Quotes That Are Powerful, Informative, and Necessary"Racism is a visceral experience...It dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth. You must never look away from this."

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Being Estranged From My Mom Is Hard. Mother’s Day Makes It Harder

Being Estranged From My Mom Is Hard. Mother’s Day Makes It HarderIt’s high time to start representing the different types of mother-daughter relationships—or lack thereof—that exist during the holiday.

By Christina Wyman Published

-

'Crying in H Mart' Is Our May Book Club Pick

'Crying in H Mart' Is Our May Book Club PickRead an excerpt from Michelle Zauner's memoir, here, then dive in with us throughout the month.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The 13 Best True Crime Books to Devour

The 13 Best True Crime Books to DevourThe definition of page-turners.

By Maria Ricapito Last updated

-

23 Black History Heroes You May Never Have Heard Of

23 Black History Heroes You May Never Have Heard OfThese are life stories worth knowing.

By Bianca Rodriguez Last updated

-

To End Sexual Abuse in Churches, Dismantle Purity Culture

To End Sexual Abuse in Churches, Dismantle Purity CultureThe Christian church’s norms provide the perfect cover for sexual predators—and leave their victims feeling like the sinners.

By Leslie Goldman Published

-

I Was Adopted by a Sex Offender

I Was Adopted by a Sex OffenderHow my stepfather's past changed my future.

By Sine Nomine Published

-

Where Did All My Girlfriends Go?

Where Did All My Girlfriends Go?Even in our hyperconnected world, true friendship remain elusive for young women looking to rebuild their college-era squads.

By Maggie Bullock Published