Ann Curry on Reporting in the Aftermath of 9/11

The former NBC News correspondent spent years reporting on human suffering. September 11, 2001 was unlike anything she had covered before.

Click here to read the complete "Reporting in Real Time" series

Twenty years ago, September 11, 2001 became—and will forever be—one of the biggest and most important news days in American history. As we remember the events that unfolded and honor the nearly 3,000 lives lost, Marie Claire asked five women journalists to reflect on covering the 9/11 attacks in real time and the lessons that can be learned today. Here, former NBC News correspondent Ann Curry describes what it was like reporting from Ground Zero in the weeks following 9/11, recalling the exact moment she heard "the drumbeats of war." Go behind the scenes of her on-air coverage, below, then read the rest of the journalists' stories here.

It began as a normal morning. It was a sunny day, and we had the usual enthusiastic crowd outside [of Today]. At 8:30 a.m., I had just finished my last newscast of the morning. Then just before 9 a.m., in the last half hour of the broadcast, the first plane hit the North Tower. As soon as we heard, as we normally do in a breaking news situation, [the whole team] started scrambling for more information—for facts and for images. At first we thought it was just a terrible accident. And very quickly we got a live visual feed. We watched [in the studio] as the second plane hit the South Tower.

It was within minutes, really, of the first crash. And that was the moment we knew that this was no accident, that we had a job to do. We were not going anywhere. We knew deep in our gut that we were under attack, we might be at war. But with whom? Technically, when the first plane hit, that was the moment; but when the second plane hit, that's when we knew that the world had changed.

There was very little information to report at first beyond describing what we all could see. So I was behind the scenes basically trying to figure out what was going on like everybody else. Then everything started happening really fast. I ran back into the newsroom, and information started pouring in. It was like rat-tat-tat, one thing after another. We were monitoring the [AP] wires, as they were reporting the facts and trying to gather this information and making sure that the people on the air were getting it. And very quickly, that person was [NBC Nightly News anchor] Tom Brokaw, who came into the studio [right away].

Ann Curry

So what we had is the North Tower hit, the South Tower hit, a plane crashed into the Pentagon, 20 minutes later the South Tower collapsed, minutes later another plane crashed in Pennsylvania, and then the North Tower collapsed. And as experienced and adept as Tom Brokaw was at reporting breaking news live, I could see he was desperate for information. So for a time, I just started gathering verifiable facts and printing them out and running the pages to the set so that he had something in front of him. I was essentially slipping him information off-camera while he was on the air until producers finally could arrive to help.

Information was really hard to come by because power was out in parts of the city, especially in lower Manhattan. Phone lines were jammed. This was before social media. We were working with BlackBerries. But bit by bit over time, information started coming in from eyewitnesses, people calling in, including one of our NBC producers who actually lived not far from the World Trade Center and who was essentially just describing what she was witnessing—people running, people covered in ash. We were able to hear from officials over the phone, but it was hard to get to people [on the ground] because everybody was in a state of horror and shock.

As I reflect back on it now, the day was a blur. I just remember I thought it would never end. And I felt helpless like everybody else. It was not until the next day that I went to Ground Zero, and I reported live from the scene every day for weeks.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

I had been trained to rush into disasters as a reporter for years, but I was nervous [to go to Ground Zero] because I had never covered something as horrific as this. From that first morning when I arrived, I noticed that everything, especially the cars, were thickly covered in ash. Everything sounded muffled. It was quiet, eerily quiet. The only sounds you would hear were the sirens, and they just never stopped.

At first, journalists were kept from getting too close, but I had this knack that I developed over many years of reporting to speak with the rank and file. Maybe it's because I come from a family with a military background (my father was career military, and I had two brothers in the military). So one New York City detective agreed to take me all the way down to the South Tower.

I'm not sure what day it was. I just remember that there was a light rain, and he walked me down through one checkpoint after another. It was as if you had walked into winter. Everything was white and muffled, like snow was on the ground. And finally, we were right down to that corner of the South Tower. At this point, we knew that the death toll would be significant. We knew that firefighters who'd rushed into the towers to rescue people had died in their collapse. When I got down to the corner where the South Tower once stood, I could see to my left a sea of firefighters standing at the ready and quietly facing the high mound of ash and shards of metal to my right, which was what remained of the South Tower. The only sound was coming from the men who were in a line carrying hand over fist buckets of ash down the mound. Hand over fist they were bringing down these buckets of ash in an effort to find people who might have survived and were buried beneath it.

Because it was so dangerous with all this metal everywhere, [the firefighters] would get hurt in this work. A call would come out that someone was hurt, and he would be brought down from the mound, and another man would step up. Those [firefighters] at the ready...I realized they were waiting for their turn, eager to climb the mound to do their part to save someone. I realized I was witnessing an immense act of courage in the face of this terrible atrocity. These men, you could see in their faces they were haunted by what they had seen. They looked as if they hadn't slept, and they looked as if they were already mourning for people they knew. It was a moment I have never and I don't think I can ever forget.

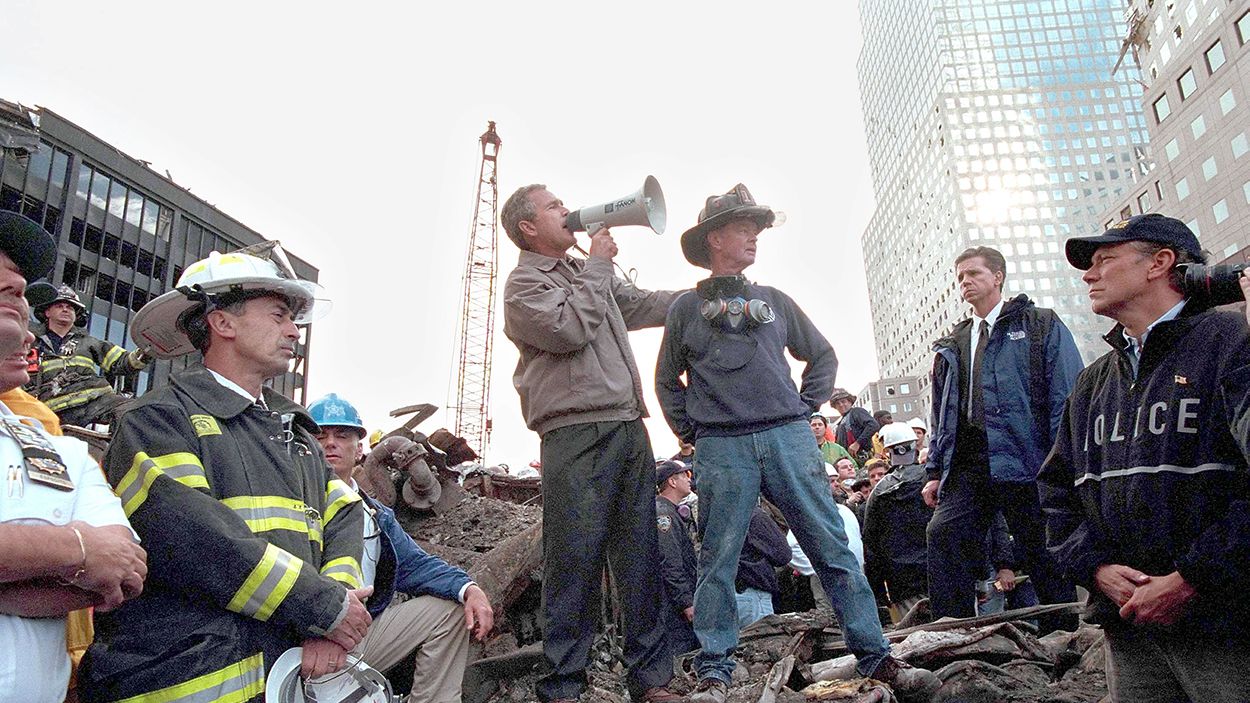

President George W. Bush speaking to first responders atop the rubble at Ground Zero, which Curry witnessed live on September 14, 2001.

About three days after 9/11, President Bush arrived. I was in the crowd when he was speaking to the firefighters through a bullhorn. They couldn't hear him. At first, he was speaking almost tentatively. It was something in his physicality and his manner as if he recognized that there were no words that one could possibly say. And he was speaking from what sounded like a prepared speech about America being on bended knee. Then somewhere behind me someone shouted, "We can't hear you." And then a number of people—firefighters I think—were also starting to shout, "We can't hear you." That was the moment when he roared back through the bullhorn, "Well, I can hear you. The rest of the world hears you."

Then he said something about how the people who did this will hear from all of us soon. And that's when I heard the drumbeats of war. The firefighters started shouting, "USA, USA, USA." It was so loud. Their emotion was so intense. And you knew that we were changed as a nation. We'd come together, and you knew there would be hell to pay.

I had two children who were very young. My apartment was downtown, where it was close enough that I could smell what was happening. There was an odor of the chemicals and everything else that was in the air. Making my way home in the dark every day, my clothes reeked. So I would come home and take off all my clothes, some days down to my underwear. I would knock at the door and ask my husband for a garbage bag, and then I would put all of my clothes in the garbage bag, and I would zip up the garbage bag and throw it down the garbage chute. Then I'd go in the apartment, almost always in my underwear, and head straight for the shower and just wash everything off. Then I would embrace my children.

My husband taped up the windows because the odor was coming into the apartment. I remember asking my husband to turn the TV off because it kept playing the towers falling over and over and over again. And I was worried about the children. They were really little. My son was in kindergarten and my daughter was in second grade. I don't remember the conversations—I just remember holding them. I felt bad that I couldn't keep it from them; I couldn't keep what was happening outside from coming into the house. That's what taping up the windows represented to me and trying to stop it from coming in through the television and trying to wash myself off before I saw them and taking off all my clothes and throwing them down the garbage before I entered the apartment. I was trying to keep [the grief and suffering] from coming into our home and trying to prevent my children from experiencing it, but how could [I]?

At one point, I saw my son playing with blocks, and he kept building up towers and knocking them down. I realized he was working out what the hell was happening. I'm starting to get emotional just talking about this because I think for all of us, there was a kind of trauma that we didn't address and couldn't address. We were a nation that was traumatized by what we had experienced. And those of us who got so close to seeing and feeling and crying with people on the scene, it was just very hard to rise from it.

After the weeks and months reporting down there, at some point I stopped going down [to Ground Zero altogether]. I stopped thinking about it. I was thinking about the things that were coming. We had the anthrax attacks [shortly after 9/11], which never were directly tied, but were believed to be somehow related. We had the drumbeats of war lead us into Afghanistan, which I covered, and Iraq, which I covered. The world, my world, all of our worlds changed. We became more unified. We became tougher and more serious. We became more worried, fearful people.

For journalists, it's hard to focus on your own emotional trauma when you're witnessing the trauma of others who have every reason to be more traumatized than you. I've covered so much human suffering. I remember when we came out of Haiti and the earthquake there [in 2010], we'd witnessed so much that there were journalists who were traumatized. After Haiti was the first time I can ever remember that there was someone who was brought in to talk to us journalists at NBC about what we had witnessed. I remember thinking wow, people are actually wanting to help us get through what we saw. I was traumatized to some degree from covering the earthquake in Haiti. It was a terrible disaster and the human suffering was great, but I think because I had witnessed so much before then, I was already on the path to kind of bury it and understand that the job meant a degree of PTSD that you had to work out yourself.

There was no therapy or discussion or journalists even generally talking to each other about what they were experiencing [during 9/11] because the focus was really on doing your job and trying to do it as well as possible and trying to be tough enough and strong enough to do it impeccably. That was the pressure. But I know that there was trauma. I saw it. I saw it in my colleagues. And I saw it really when, so soon after the attack, these letters with white powder started arriving at NBC News, as they were beginning to arrive at a number of news organizations.

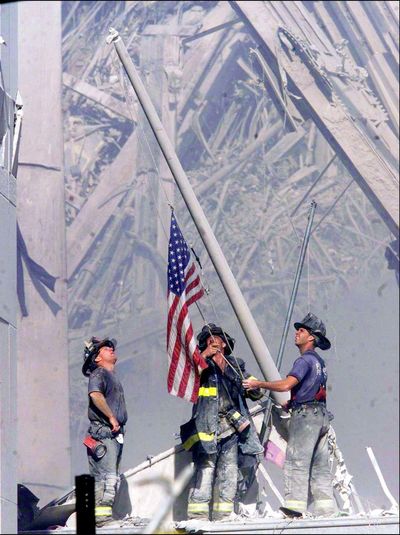

Firefighters raising the American Flag atop the rubble at Ground Zero.

I had a copy of this iconic photograph of firefighters standing in front of the shards of metal in the rubble of the South Tower and raising the American flag. I wanted to hang it in my office, so it was against my couch ready to be hung up. A producer walked by my office, and she was very upset. She said, "I don't want to see that photograph. It's enough. It's enough." She was furious, not only because of 9/11, but because it was right after we'd had the big meeting to tell us all about the [anthrax] letters and how we all needed to take Cipro [(a prescription antibiotic that reduces the chances of someone getting sick and dying if they've breathed in anthrax germs)] because they weren't sure who potentially had come in contact with these letters and whether or not they were anthrax. I immediately knew there was trauma and this was re-traumatizing people. I turned it about-face so people couldn't look at it. I never hung the photo.

In some ways, the two decades feel as if they have passed, but in other ways it's as if time has stopped. So much has happened. So much has changed. And I feel the weight of that in terms of the stories that I've covered. All of the trips into war zones and interviews with leaders, including in Afghanistan and Iraq and Pakistan and Syria. Being in Somalia reporting from what looked like a training lab by Al-Qaeda rebels, where [my team on the ground] was shot at. Covering the war in Syria and trying to escape being bombed there. Interviewing the president of Pakistan and having a hotel next to mine bombed. As I think about it, the emotions rise and the memories of the forlorn, haunted looks on the faces of the firefighters come back immediately.

One of the most important things I've learned is that we are far more resilient than we know. I also have learned that among us there are heroes—and they are sometimes people you might not guess. As haunting and as traumatizing as covering that atrocity and the wars and the human suffering that it unleashed was, it's something I will never regret because there is a privilege in giving voice to the people who have been impacted by all of those events. There is a privilege to letting those people be heard, whether they're the victims of 9/11, whether they're the courageous ones who stepped in and risked their lives to help others, whether they're the soldiers who rose up and risked their lives, their safety, to fight back. The civilians who were caught in those wars, the people who were innocent and had nothing to do with any of it. All of those people deserve to be heard.

It has been a privilege to tell the world of their courage. I would not trade that job for not having this trauma or this grief. Journalism is a service job. When you face and report on the truth of what's happening in our world, you are more likely to meet the challenge if you can work for [your fellow] people and not for the people who pay your check. If you can ask the questions and interview the people who will have the answers that the people want to know, if you can respond to a story in the same way as an EMT responds in an emergency or a firefighter or a police officer or an emergency room doctor needing to meet the wounded, someone who is in desperate need of care, if you can respond with truth in that manner, you will meet the challenge that the times ahead will demand.

RELATED STORY

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.