I Narrowly Avoided Becoming Another Black Maternity Statistic

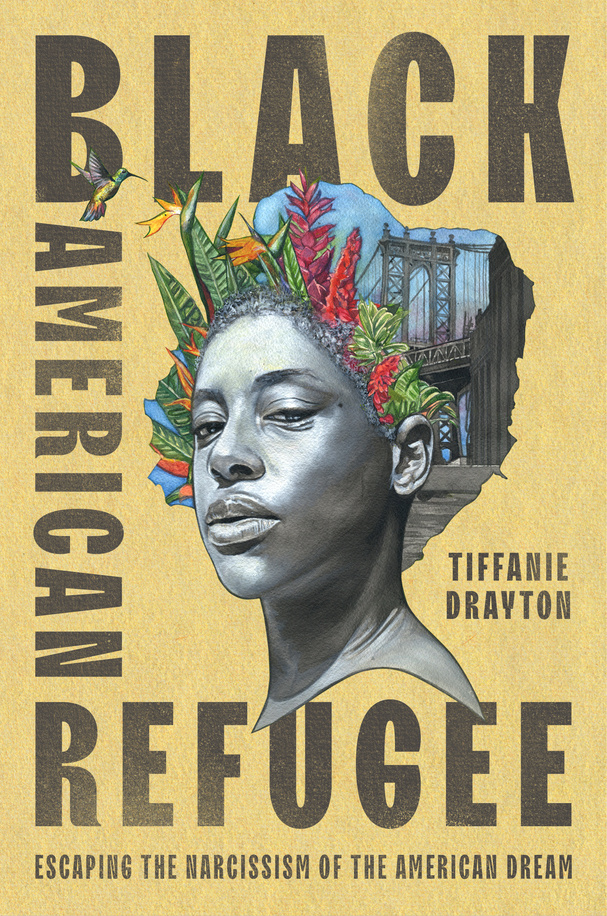

In her new memoir, 'Black American Refugee,' Tiffanie Drayton writes about the subtle (and not-so-subtle) ways that systemic racism impacted every area of her life.

“Is this how I die?”

Every time a victim returns to their abuser, the abuse escalates. Eventually, it can become fatal. I first began to be haunted by thoughts of my death in my early 20s. Such thoughts were fleeting then, appearing briefly and then vanishing like a spirit. They were conjured by the images of lynched black bodies or fears that I had some undiagnosed medical condition. My thoughts of my own death became more frequent as I began to better understand America’s cycle of abuse with its black populace: The way destruction and death always seemed to follow times of progress. I wondered if my time would come after high school? Or maybe college? If I would be gunned down for a traffic violation on my way home from my graduation? Or struck by a stray bullet while enjoying my favorite sitcom on television? Would violence find me in my most prideful moment in the same way that after Reconstruction came a vicious wave of white terrorism from organized groups like the Ku Klux Klan, the White League, and White Camelia, that claimed the lives of thousands of black people. Or how after Black Wall St. was erected, it was burned and bombed in a racist riot started by white men under the false claim that a black man had tried to rape a white woman. Or in the way many Civil Rights Leaders were assassinated or exiled and groups like The Black Panther were targeted by the CIA and FBI. Did the rise in white supremacist hate groups and white violence which immediately followed the election of Obama, America's first black president, threaten my death? Would I become another black health statistic? Eventually, I came to recognize the whispering voice in my mind as the part of my black consciousness that understood my mere existence repulsed, defied, and threatened the tenants of white supremacy.

To be a black woman is to live, either consciously or subconsciously, carrying the burden that your death or destruction is imminent. Death trails your car at night when you are driving home from work and spot a police car in your rearview mirror. It is by your side at every doctor’s appointment. Its threat grows with your belly during every pregnancy. It lurks behind every promise of love from a black man. You are constantly haunted by statistics and they never look favorable.

Compared to all other racial groups, Black women are most commonly killed by firearms.

According to the 2010–2012 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, nationally, 45 percent of Black women experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime.

According to the CDC, “Black women ages 25–29 are 11 times more likely as White women in that age group to be murdered while pregnant or in the first year after childbirth.”

As the scroll upon which your hardships are written into reality endlessly unfurls, it moves beneath you like you are running on a treadmill that you cannot keep up with, high above a canyon.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

In 2017, African American mothers were 2.3 times more likely than non-Hispanic white mothers to receive late or no prenatal care.

Black women are three to four times more likely to experience a pregnancy-related death than white women.

Black women are more likely to experience preventable maternal death compared with white women.

I was pregnant and fearful of becoming just another statistic: One of the hundreds of black women who die every year [from pregnancy related causes] in the United States of America, the country with the worst maternal mortality rate in the entire industrialized world. Where Black and Native American pregnant women are two to three times more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes than their white counterparts and black babies are more than two times more likely to die as infants as white babies.

Upon registering for Medicaid, the state automatically assigned an HMO, which decided where I could access services. My assigned HMO meant I could go to the closest health center not too far away from my Jersey City residence. I called and scheduled my first appointment, thrilled to find out details about the tiny new life growing inside of me. I excitedly imagined exchanging stories about pending motherhood or getting advice from other mothers in the waiting room.

“Nope, I don’t care if it’s a boy or a girl,” I proudly rehearsed in my head, anticipating what interested mommies-to-be would ask.

The doctor’s office was in a two-story, brick front building that looked just a little run down, right across the street from a park that frequently had huge fights that would end in police using pepper spray and tasers to disperse groups of rowdy black children during the summertime. A nurse directed me to a seating area to fill out a packet of information attached to a clipboard and wait for my name to be called. Two other young black women in their 20s were already seated. One was heavy set and had an enormous belly protruding from her shirt which uncomfortably clung to her body and barely covered her navel. She gave me a small welcoming smile, revealing a gap where her front tooth should’ve been, when I took a seat across from her. The other, a petite woman with a tiny, perfectly round bump, wearing black and purple Jordans, skinny jeans and a hoodie, sat nearby chatting loudly on her phone. The room wreaked of poverty and hardship.

“They best not tell me I have to come back again today, cuz I have to work,” she declared loudly.

“I hate when they be doing that,” the other girl piped up.

“It happens a lot?” I questioned.

“Umhuh,” she responded.

“The last time I missed the whole day and the boss was getting on me about it,” the other girl continued her conversation on the phone.

I shrugged.

“You look like you about to pop,” I said with a chuckle, trying to lighten the mood.

She gave me a weak smile.

“I’m 8 months,” she exhaustingly replied, “they say I gained too much weight with this pregnancy, but most of the time I feel like all I have the energy to do is eat.”

I lowered my eyes in an attempt to hide the judgments brewing internally. Mom always warned me that I struggled immensely with concealing my opinions, even when I didn’t mutter a single word, so I avoided her gaze to avoid giving myself away. I took note of each of these women’s struggles and tried to relieve my own circumstances of such burdens in my mind: 1. I worked from home and would never struggle between making appointments and making a living and 2. I was an avid exercise enthusiast, so there was no way in hell I would get as fat and dejected as the woman sitting across from me. I was nothing like those women, I concluded.

“Drayton,” a nurse interrupted.

I waved the women “goodbye” and sprang out of my seat towards the examination rooms.

“Room one after you fill this up in the bathroom,” the nurse guided, handing me a cup to pee in.

I relieved myself and handed the cup off to the nurse, dashed towards the room and then plopped down on the examination table, my legs wagging as they dangled above the ground, like a child.

“The nurse will be with you shortly.”

The walls in the room were bare, except for a poster showing a diagram of the female anatomy and a peach-colored skin pregnant woman and a fetus turned upside down in her belly. I scanned it for any insights about what was about to happen to my body. Then another nurse, a short black woman with green scrubs, came in, took my weight, height and blood pressure.

'Drink some water and make sure you put your feet up and get rest.' And just like that, the appointment was finished. I would not be scheduled to see the doctor for another six weeks.

“The doctor will be with you shortly,” she said, gently closing the door as she left.

The doctor popped right in shortly after her departure. He was a meticulously dressed white man with coiffed hair, wearing a suit, perfectly fitted pants and a tie.

“So, how are you feeling, Ms. Drayton?” he questioned.

“I’m pretty alright.”

He perfunctorily flipped through my chart and then sat in an office chair across from me.

“Alright, well I’m going to have the nurse schedule your next appointment for three weeks from now to get more details on your medical history,” he haphazardly stated. “Drink some water and make sure you put your feet up and get rest.”

And just like that, the appointment was finished. The nurse scheduled me to meet with the head nurse in four weeks and I would not be scheduled to see the doctor for another six weeks.

“There’s no way this is right,” I told my mom over dinner. “I’m not sure if he was there auditioning for America’s Next Top Model or to be the host on ‘Queer Eye’.”

The next day, I spent hours on the phone trying to change my HMO plan, so I could beg my gynecologist to take me on as a pregnant patient. At first, she was hesitant to take on a patient already well into pregnancy, who received care from another doctor. She had a full roster of clients and already spent seven days a week running between the delivery room at the hospital and her office across the street. But my begging and insistence proved successful.

She did an ultrasound that very same day of my first appointment and printed pictures for me of the tiny life growing in my belly. I peered at the black-and-white image trying to decipher the baby's head, hands and mouth but really just saw a black shadow sprinkled with white specks.

“We’re going to run a couple of tests and do some bloodwork,” she said with a smile. “I’m glad you came in now, because you almost missed the timeframe for some of these tests.”

They scheduled my next appointment for six weeks from that one, but I got a call within seven days.

“Ms. Drayton,” the familiar voice of the doctor’s secretary answered. “You are going to have to come down and see the doctor.”

They got back my blood work and found an abnormality. My hands perspired and quivered as I sat in the examination room awaiting the news of the verdict. I tried to suppress my worst fears, but scary thoughts swirled all about like ghosts haunting a house.

Was the baby ok? Was the baby alive? Did I have cancer? Which one of us was about to die?

The door swung open and the doctor appeared with a clipboard in her hand. She flipped through the chart, peering at tiny numbers written in boxes labelled “Leukocytes,” “hemoglobin,” “platelets” and other words then unintelligible to me.

“Have you been feeling alright lately?” the doctor began.

The question caught me off guard.

“Your tests show that your T4 levels are really low, which indicate hypothyroidism,” she continued.

Hypothyroidism is serious. After a quick google search I learned that left untreated, it can cause high blood pressure, anemia, muscle pain and weakness. It also would’ve significantly increased my odds of having a miscarriage and premature or even still birth. Babies whose mothers don’t have enough thyroid hormone circulating in their blood during pregnancy are also more likely to suffer from mental retardation, because the hormone is needed for proper fetal and neonatal brain development. I clicked through link-after-link of webpages on the subject, before I just sat in front of my computer with a blank stare. My eyes swelled with water, but I tried to choke back the shock and horror of only narrowly avoiding becoming just another black maternity statistic.

Adapted from BLACK AMERICAN REFUGEE, by Tiffanie Drayton, published by Viking, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Tiffanie Drayton.

Tiffanie Drayton is a Trinidadian-American writer who loves to share the beauties and hardships of her experiences as a black woman. Find her on Twitter @draytontiffanie.