My Dad Got Cancer, and Then He Killed Himself, and I'm Still Picking Up the Pieces

A 13-year journey with no end in sight.

I was only a junior in college.

Following a short four-month battle with sinus cancer, my father unexpectedly committed suicide, throwing my life into a tailspin that I'm still working to get through—13 years later—today.

His death was violent and unnatural. There was a palpable ugliness to that wrenched us into a new reality the second my mother found him in our small bathroom one March morning.

I'd been sleeping when it happened, and I'll always wonder why he chose that moment to end his life.

I was jarred awake by my mom's screaming, and I froze in my bed; I didn't know what to do. I stayed in my room, feeling utterly helpless, until the police came and took his body away. Maybe I subconsciously thought that if I didn't see my father's body, none of this nightmare would be real. Maybe I could just go back to sleep and all this would just be a horribly bad dream?

Insert "I'll always wonder why he chose that moment to end his life."quote here

Sadly, though, everything was all too real. Over the next few months, my whole family sank into a similar kind of numbness. I wonder how we got through that time—we were just running on autopilot, I think. If we stopped for a minute and really thought about everything that had happened, our loss would have consumed us.

I soon learned that grief from suicide is known as "complicated grief," which occurs when the death is especially traumatic. The mourning can be overwhelming and long-lasting.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

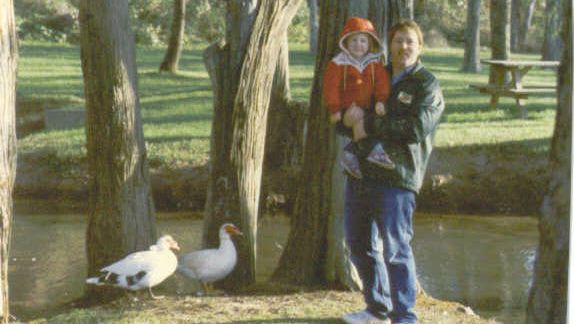

'The author with her late father'

Although I felt anger after my father's death, a succession of strong and powerful emotions soon followed. Sadness over losing one of the most important and influential people in my life. Confusion—why did he kill himself in the first place? What was he thinking? Regret—the feeling of wondering if I could have somehow prevented it. Maybe if I had just woken up sooner or saw signs in the days leading up to his death, I could have somehow saved him.

All these emotions wanted my immediate attention, and I just didn't know which one to focus on first.

A few years into my grief, my mom and I attended a National Survivors of Suicide Day conference in Chicago, a day where survivors come together to share their stories and give support to one another. While I listened to everyone's stories, I couldn't help but feel out of place. It was as if I was looking into a world full of these experiences that had nothing to do with my life—I just couldn't identify with anyone, even people who had lost a parent.

When it was my turn to speak, I shared my story, but I felt like it wasn't really "my story." They were my words, sure, but this was the story of someone else's life, not mine. It was as if I was sitting outside the scene and looking in; everything was so remote, so foreign, so unfamiliar.

"In grief, feeling like you fit in somewhere—anywhere—is a very powerful and necessary thing."

In fact, I didn't seem to fit in anywhere. My father had cancer, yes, but that's not technically what he died from—so was I really a member of the cancer survivors community too? And although he committed suicide, he'd never had a history of mental illness, so how could I be the traditional survivor of suicide? In grief, feeling like you fit in somewhere—anywhere—is a very powerful and necessary thing, so to feel like I was alone was even more isolating.

I'd wanted to connect so badly to something, anything, that would make me feel like I was understood. My father was gone and my grief was real—and more than that, it mattered. My family understood, sure, but for some reason, I wanted everyone else to understand as well. I started feeling like I was trying desperately to still connect with my father, to bridge my former life with the one I'm living now.

Eventually, I began seeing a therapist. Over time, that story and those words became my story. Giving a voice to so many of my emotions, like how I'd do anything to see my father just one more time. This isn't to say that my family wasn't there for me —I don't know how I would have gotten through the last 13 years without them. But talking to someone removed from the experience really helped in giving me a sense of perspective—and even the beginnings of a bit of closure.

'The author with her late father'

We talked a lot about my anger—I was once a laid-back, easy-going person, and because of the grief I was short with people; it seemed like every little thing got under my skin. My anger toward my father had been redirected outward—to the rest of the world.

We talked about how I loved my father but was so mad at him for what he did. For years, I'd struggled with the idea that not being mad at him meant that I condoned what he did; I didn't think I could ever be both. But my therapist helped me see that I could live, even heal, with both. It didn't mean I loved him any less or that it was "okay" for him to leave us; it just meant I was working to reconcile my emotions, which, I discovered, was the first step in the healing process.

The biggest lesson I've learned, though? There's no express lane when it comes to your emotions. Feeling them isn't something you can just rush through as if they're one more item to check off on your daily to-do list. For so long, I tried to push my deeper feelings under this giant blanket of anger.

"There's no express lane when it comes to your emotions."

I effectively put myself on an island and cut myself off from feeling any other emotion, even the ones that were healthy. And especially the ones that helped me remember happier times with my dad. Because, really, that's what grief is: It's like peeling back the layers of an onion and examining each of them individually. In grief, each emotion is a layer unto itself and needs to be felt fully and completely.

I started slowly peeling back those layers and saw a different portrait of myself underneath. It wasn't the portrait of someone with blinding rage and seething anger. Instead, there sat a hurt and scared little girl who lost her father and missed him desperately. She was just trying to find her way through the confusing maze that had become her life and was doing the best she could.

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-TALK.

Melissa Blake is a freelance writer and blogger from Illinois. She covers relationships, disabilities and pop culture and has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, Harper's Bazaar, Good Housekeeping and Glamour, among others. Read her blog and follow her on Twitter.