"The Last Time I Saw Her"

Six women from across the country open up about the sisters, daughters, and mothers they lost to mass shootings.

Mary Kay Mace lost her daughter, Ryanne

The last time I saw my daughter, she had come home for a weekend from college. Her school was just a 45-minute drive from home, so my husband and I saw her pretty often. On that visit, we gave her a little bit of ribbing about her car—she didn't keep it very neat. It was like a rolling junkyard. She laughed and said, "Yeah, yeah, I know." Before she left, I gave her a hug and said, "We'll see ya, kiddo. Love you."

My daughter, Ryanne Mace, was killed in a mass shooting at Northern Illinois University on February 14, 2008, Valentine's Day. She was sitting near the front of her ocean-sciences class when the gunman burst in the room. She was 19 years old.

Ryanne was my only child. She loved offbeat humor: Monty Python, Stephen Colbert. She befriended all types of people from all walks of life—she had a soft spot for the underdog, the kids who weren't popular. She didn't think anyone should be an outcast. She was pursuing a degree in psychology because she wanted to counsel people face to face and help them talk through their problems. If she had known her shooter, she would have tried to befriend him.

On the day of the shooting, I was at work. My boss's wife called, saying there had been a shooting at NIU. My mind immediately went through all these protective things, like what were the odds that she was even on campus. I kept calling her phone. I finally reached one of her friends, who said yes, she was in that classroom. We got in our truck and took off. We stopped at the hospital and talked to the first person we saw with a clipboard. Ryanne was not on the list of the injured. I thought, Thank goodness, she's not hurt.

A campus police officer asked us a lot of questions. We kept going back and forth because an unidentified victim had a tattoo. I kept saying, "Ryanne doesn't have a tattoo." Well, she did have a tattoo. We just didn't know.

Ryanne was a few months short of turning 20 when she died. For her birthday, my husband and I decided to take her ashes out to Oregon, where we lived when she was a little kid. On the way, we hit all these places she had visited and wanted to go again. We went to the Black Hills, Mount Rushmore, Devils Tower. We scattered her ashes in Oregon. Then we drove back a different route, through places she had never been. Here we were, forging a new path without her.

Jillian Soto lost her sister, Victoria

The last time I saw my sister, she was home late from school, eating dinner, just a typical evening. It was a couple weeks before Christmas, her favorite holiday. We talked about how it would be fun for the family to wear "feetie" pajamas for Christmas. I was getting ready to leave for a ski trip that night, so I finished packing and ran out the door. I never said goodbye, never thought twice about it.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

My sister, Victoria Soto, was killed the next day, on December 14, 2012, in the classroom where she taught at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut. She was 27 years old.

My sister taught me everything—how to roller-skate, what to wear, how to straighten my hair. Growing up, I admired everything about her. I went to the same college as she did, hung out with her and her friends, borrowed all her clothes. She was that person I called when I needed to know what to do about a boy.

We have a picture of her from before I was born: She was at Disney, looking at the flamingos, and you could just see the awe on her face. She started collecting flamingos: She had flamingo bedsheets, pictures, stuffed animals.

This past August, we opened the Victoria Soto School, an elementary school in our hometown of Stratford, Connecticut. There are pictures of flamingos in the main office, and the staff wears pink shirts.

In the days after the shooting, the world stopped and grieved with us. And then, the world started going again. But not for us. We were just going through the motions. That's what happens when you lose someone so suddenly, so unexpectedly.

That day took away so much from me—not just my sister, but my sense of security. Now I need to know where the exit is; I look for places to hide in large groups. The worst part has been watching my family fall apart. Vicki was my mother's firstborn. My mom is so heartbroken, and I can't fix it. I can't take away that pain for her.

Every time another shooting happens, I actually get physically sick. I feel like the walls are caving in. I can't breathe. When people tell me my sister is in a better place, I get angry. She was already in a good place. That school and the students—she called them her kids—were everything to her. She died doing everything she could to keep them safe.

This past September would have been my 27th birthday, but I've chosen not to celebrate being 27 because it means that I've outlived my sister. In my eyes, I'm still 26 and I'm just going to skip to 28. At the same time, I have made a resolution: I'm in control of my own life. I'm in control of my happiness. I'm getting that back. I'm going to honor my sister every day—I'm going to smile every day because that's who she was. She loved life. I have to do it for my sister, and for my family, and for myself, because I can't allow someone else to win this battle.

Reverend Sharon Risher lost her mother, Ethel, and her cousins Tywanza and Susie

The last time I talked to my mom, we discussed one of her favorite things in the world: perfume. As a mother of four girls, she would always spray my sisters and me for special occasions when we were kids. Then she would hide the bottle because she knew we would be spraying it all over the place.

This past June, she called and said, "Ooh, I smelled this Banana Republic perfume—I sure would like to have some of that." I said, "Ma, would you like me to buy you that perfume?" I bought a bottle, but I didn't send it right away.

It was delivered to her the day after she died.

My mother, Ethel Lance, was shot and killed in the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 17, 2015, along with two of my cousins, Tywanza Sanders and Susie Jackson.

My mom loved that church. She was a member for more than 40 years. She worked there as a sexton, keeping the church neat and clean, to make a little extra income to help my niece in college. She had such a work ethic.

Cousin Susie was a matriarch of the church, one of the oldest members of our family. If she saw you chewing gum in church, she would give you the stinky eye. My cousin Tywanza was a young man with an infectious smile, a big heart. He had such promise to be whatever he wanted to be.

When I heard about the shooting, a scream came out of me. To have three people taken out of your life is just overwhelming. It's only because of my faith and because of the faith of all the people in that church that I'm able to continue to walk, to continue to get out of bed.

My mom and I would talk at least three, four times a week. She would call me on Sundays; she would say, "Girl, Reverend Pinckney throw down today."

All my life, my goal was to make my mom proud of me. When I had an opportunity to preach in the Emanuel AME Church, well, I went in that church and turned it out. My mom sat in the front row, just crying.

Forgiveness is a process. I'm not there yet. Being without my mom, I don't have the chance to call her on the phone, to ask her how to cook gumbo, to sleep in her bed with her when I go home. But I know that one day, when I get to heaven, what a day it will be. What a day it will be when I get to be with my mom again.

Sandy Phillips lost her daughter, Jessica

The last time I heard from my daughter, it was late and I couldn't sleep. She was at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado with her best guy friend—they were at a midnight showing of The Dark Knight Rises. I was planning to visit her the next week. She texted me, "I can't wait to see you. I need my mama." And I wrote back, "I need my baby girl."

Less than 40 minutes later, she was shot six times. One bullet left a five-inch hole in the side of her face. That was July 20, 2012, and it feels like yesterday.

My daughter, Jessica Redfield Ghawi, was 24 years old. She had one semester left of college, where she was studying broadcasting and journalism. She wanted to be a sportscaster—she was so determined and tenacious. She was already respected by men who had been doing the job for many years. Actually, one of them—kind of a curmudgeon—told me that Jessi's passion had rejuvenated him, like she was a light being brought into the room.

She was planning to go to a job interview on July 21.

During the shooting, her friend called me from the theater. I could hear the screaming in the background. I said, "Where's Jessi?" And he said, "I'm sorry." When I realized she had been killed, I guess I started screaming, although I don't remember it. I don't remember much after that.

A lot of people say that when someone gets shot, the adrenaline kicks in and the person doesn't know what's happening. But Jessi did know. The first bullet hit her in the leg and she fell. She said, "I've been hit." The bullet went through that leg into the other leg. While she was falling, she was hit three more times in the abdomen. Her clavicle was shattered. She was screaming, "Someone call 911!" Then she was shot in the head.

It's the little things you miss the most. I miss her texting me pictures of her trying on clothes, or asking me what I think of a new haircut. I miss the way she flipped her hair, the sound of her heels as she walked up to the front door, the way she laughed—she was not a giggler, she was a belly laugher. All those littles.

Six weeks before the shooting that ended her life, Jessi had just missed another shooting at a mall in Toronto. Shots were fired in the food court just two minutes after she had left that same area with her boyfriend. It deeply affected her. She went home and wrote on her blog, "Every second of every day is a gift."

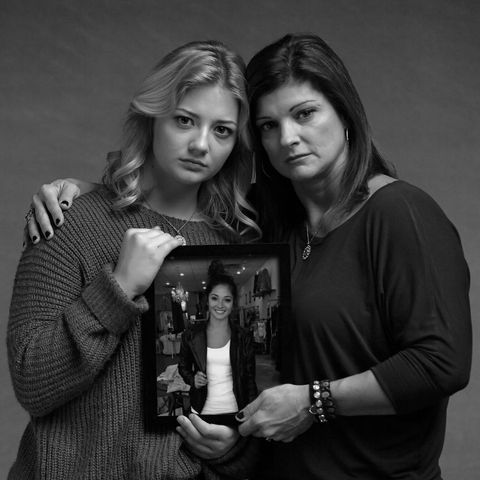

Ali Breaux (pictured here with her mother, Dondie) lost her sister, Mayci

The last time I saw my sister, she was home for a weekend to visit with our family. She was 21 years old, studying radiology in college. I was 15, getting ready to practice driving, and she was supposed to come with me. But she was scared to drive with me, and I don't blame her. My dad came instead. I really wish I could have had that time with her.

My sister, Mayci Breaux, was shot four days later, on July 23, 2015. She died while watching Trainwreck in a movie theater in Lafayette, Louisiana.

Mayci was always there for me through everything, giving me advice. She made me realize that things that seemed big were actually really small. She would say, "It's just high school—it's not that big of a deal." She would tell me not to feel sorry for myself. It made me realize: If you just sit around and feel bad for yourself, you're not getting anywhere. She helped me see the big picture. She built me up.

She also made me laugh. Growing up in the town of Franklin, Louisiana, we rode four-wheelers, jumped on the trampoline. We both loved to dance, too—ballet, hip-hop, jazz, lyrical. She especially liked hip-hop.

On the day she was killed, I was at a dance convention in New York. I was dancing when I suddenly felt this huge pain in my neck. I just kept pushing through, because that's what dancers do. Later, I learned that the pain had come at the same time my sister was shot.

I was in the hotel room that night when my mom came in, hysterically crying. She said Mayci and her boyfriend, Matthew, had been in a shooting. And that's when the shock hit. I just kept asking God, "Please, don't take her away." I couldn't see my life without her.

Late that night, we learned she was gone. I couldn't talk, really. I was just a statue until I got home. That's when I realized the things we used to do together were gone, like when I would come home on Friday nights and she would be there, and we would stay up late and talk. That's when I lost it.

Matthew was shot, but he survived. He told me that right before the shooting, Mayci had gotten a joke in the film really late, so she was laughing really loud, seemingly at nothing because the joke had passed. She had an infectious laugh. That was his last memory of her.

Back at school, I could feel the stares of everyone. I kept reminding myself that no one knows how this feels. I had to keep going because there was nothing else I could do. I joked around with people because that was my usual thing. Since Mayci was so hilarious, I didn't feel guilty for still laughing because she would want me to be myself.

I had a million moments with Mayci. But if I could tell her one thing now, I would thank her. If it wasn't for her, I would not have been this strong.

Jenna Yuille lost her mother, Cindy

The last time I saw my mom, we were cross-country skiing with her husband, up near Mount Hood in Oregon. It was two weeks before Christmas, and we took a bottle of champagne and hid it by a tree. Our plan was to go and dig it up for New Year's.

A week later, on December 11, 2012, my mother, Cindy Yuille, was shot and killed at the Clackamas Town Center mall in Portland, Oregon.

My mom was not a mall person. She was a total hippie mom: She loved her garden, loved being in nature. She backpacked, camped in the snow, loved going on hikes. She really cared about the Earth. To save trees, she sewed her own cloth gift bags instead of using regular wrapping paper. She worked as a hospice nurse, taking care of people in their homes as they were dying.

On that last ski trip, she asked if I was going to get a Christmas tree. I said no. I was 23 years old, and I felt busy and didn't want to bother. I came home from work that Monday and there was this little Christmas tree outside my door with a box of ornaments and lights. I knew it was from her. It was just the kind of sweet thing she would do. I called and thanked her. That was the last time I actually spoke with her, just a normal, "Hey, thanks, Mom." The next day, she called me in the morning, but I didn't pick up my phone because I was at work. She didn't leave a message, which was not unusual. I called her back a little later, and she didn't answer. The shooting happened that afternoon. I still think about that: Gee, I wonder what she was calling about. I'll never know.

I saw the news of the shooting on Twitter while I was at work. I called my mom. I don't normally do that kind of stuff, but I just figured I'd check. She didn't answer. I called the house and asked her husband, Robert, if he knew where she was. He said she had gone shopping. I knew that she would have gone to the mall—it was two weeks before Christmas, so it would make sense for her to be there. But, I figured, she's probably fine. There were thousands of people there. What were the chances? You never expect something like that to happen to you or your family. It took a whole year for it to sink in and actually become real.

In the weeks after the shooting, our mailbox was stuffed with cards from the families she had cared for. It was nice to know that so many people loved her.

Eventually we went back for the bottle of champagne, Robert and my little brother and me. The three of us went back to that same spot on the mountain where we'd been with my mom, and we tried to dig up the bottle. But we couldn't. There had been too much snow, and it was buried too deep.

Special thanks to Everytown For Gun Safety for their help with research and sources.

This article originally appeared in MarieClaire.com's Women and Guns feature.

Abigail Pesta is an award-winning investigative journalist who writes for major publications around the world. She is the author of The Girls: An All-American Town, a Predatory Doctor, and the Untold Story of the Gymnasts Who Brought Him Down.