The Very Big Love: 47 Siblings, 7 Mothers, and 1 Father

Christmas with my polygamous family was usually chaotic — sometimes we were on the run from the Feds. But it was beautiful, too.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Marie Claire Daily

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Sent weekly on Saturday

Marie Claire Self Checkout

Exclusive access to expert shopping and styling advice from Nikki Ogunnaike, Marie Claire's editor-in-chief.

Once a week

Maire Claire Face Forward

Insider tips and recommendations for skin, hair, makeup, nails and more from Hannah Baxter, Marie Claire's beauty director.

Once a week

Livingetc

Your shortcut to the now and the next in contemporary home decoration, from designing a fashion-forward kitchen to decoding color schemes, and the latest interiors trends.

Delivered Daily

Homes & Gardens

The ultimate interior design resource from the world's leading experts - discover inspiring decorating ideas, color scheming know-how, garden inspiration and shopping expertise.

It was the night before Christmas. We children ate popcorn balls while two of the mothers strung a clothesline from the west wall by the front door through the parlor, living room, and dining room to the east wall. Then they gave each of us a clean white knee-high stocking to hang on the line with a clothespin. "In the morning it will be filled with goodies and presents," one mother said, her eyes sparkling. "If you've been good enough," another teased. "Yes," said another, smiling mischievously. "There have been times this year when you definitely deserved coal instead of candy!"

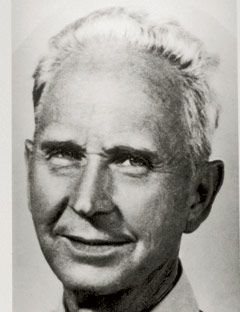

Earlier that night, we gathered in the parlor while the mothers, their arms laced around each other's waists, sang hymns. Then our tall, slender father, wavy platinum hair framing his high forehead, leaned forward and caught each of us with his intense blue eyes and spoke of his love for us. He also spoke of his devotion to the Gospel and the Principle of Plural Marriage to which we all — each of his 35 children — owed our lives. He spoke of treading in the footsteps of his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, and of the first modern-day Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith Jr., keeping the same covenant God made with Abraham, to make his seed righteous and as numerous as the sands of the seashore.

Throughout his talk, my father's seven wives, dignity carved in their faces, stood sentry, reminding us to fold our arms and listen. All of them bounced babies and shushed toddlers. Even my father's legal wife, the one who could go out in public on his arm because she had a marriage license, had finally been blessed with children after 12 long years of waiting and praying. The other six mothers had married him in a spiritual ceremony, each of them eager to be with the promising young doctor slated to lead our fundamentalist group. To defend themselves and my father against the authorities, the plural wives hid when obviously pregnant, venturing out of their homes only in an emergency.

This Christmas Eve, the youngest of our father's wives had joined us for the first time in months, holding a newborn tightly swaddled so the baby couldn't kick. My mother explained in a whisper that swaddling made the baby feel safe and taught structure and discipline. The self-restraint would prepare him for the rigors of life in a fundamentalist world.

As the sun slipped low, we gathered near the woodpile where my father kindled broken stall slats, logs, and dead leaves, then wrestled a bushel of potatoes from the root cellar and tossed the tubers into the fire one by one. Turning to warm our backsides, the older children spoke of previous Christmases — the one spent in Mexico and the one spent without our father in 1945, almost a decade earlier, when he served eight months in the Utah State Prison for living the Principle of Plural Marriage. Around the fire, we expressed our love for each other, for the doctrine of eternal family, and the knowledge that we would be together beyond death. And then we pulled our potatoes from the coals, tossing them from hand to hand until we could bite them open and hold them out for salt and pepper.

In our absence, the mothers worked furtively, watching each other's babies as they put the finishing touches on the Christmas dinner and treats: My mother baked "crybaby cookies" (so named because they always made you cry for more) from a dough dotted with gumdrops, chocolate chips, and coconut. Then she helped her sister wives with their specialties: Aunt Sally's sticky pecan rolls, Aunt Rose's heavenly white bread, Aunt Emma's pine nut turkey stuffing, Aunt LaVerne's peanut butter fudge. Aunt Lisa stripped the pinfeathers from the turkey as Aunt Adah* took a paddle to the cream, churning fresh butter for the next day's feast.

Every night for weeks, the mothers had stayed up late to embroider doll faces and dish towels, to stuff sock monkeys and flannel bears. We had little money, but our father, who was a naturopath as well as a GP, had received a huge bolt of peculiarly patterned cloth in return for delivering someone's baby, so our mothers made the most of the barter. Sometimes they grew giddy from lack of sleep, and we would be awakened by riotous laughter.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The Saturday before Christmas, my father had crowded six of us at a time into the cavernous backseat of his Hudson, driving across the valley to the polygamist-owned co-op where each of us selected a pair of Christmas shoes. Then we piled back into the car, holding our shoeboxes tight so my father could take us home and get a new load of children. The last trip was with his wives — all eight of our parents crowded into the Hudson, waving good-bye as they cautioned the older children to watch out for the toddlers and babies.

We did our best to convince our neighbors, as well as the school principal and teachers, that we were good citizens, despite our peculiar way of life. But often we were ridiculed, the word plyg spoken like the slur it was. (I will never forget the pain of hearing from my best friend that her parents would not let her play with me anymore because I was a "plygie kid.") Still, some people accepted us without judgment, which encouraged us to strive for excellence in the dangerous world beyond our home, a compound of three modest houses in Salt Lake City.

Life inside was governed by secrets held by seven women who shared a husband. Secrets protected us from the police raids that could put our parents in prison and from social workers who could send me and my siblings to live with strangers. Secrets also banked the fires of jealousy within the family — kept us from comparing ourselves with one another, suspending us in a luminous innocence. But sometimes my curiosity drove me to sneak into the other mothers' rooms and riffle through drawers and closets. I wanted to know more about these women who claimed one night a week with my father. Were they like my mother? Living with secrets every day, I'd hunger for a place where everything lay open to the sun.

On Christmas morning, as the 35 of us stood patiently, my father drew back the floral drape separating the kitchen from the parlor with a flourish. The big fir tree my brothers had brought down from the mountain stood in the corner, glittering with glass ornaments. Mario Lanza sang "O Holy Night" on the Victrola. The gifts beneath our bulging stockings stretched the length of the clothesline.

We rushed into the room. Beneath the stockings, my favorite doll was sitting with other dolls in matching dresses at a child-size table — actually the top of a wooden spool the mothers had affixed to a leaky metal garbage can and painted red. And there was a doll house with a pitched roof, crafted by our father, while each room had been decorated by our mothers with furniture fashioned from matchsticks, bits of cloth, and medicine jars. "You must share everything," the mothers chided when we wrestled for this doll or that bed. We knew about sharing, and so we moved into an easy, practiced harmony. But when our mothers swept the dolls into a canister so that we could help prepare breakfast, we protested with tears.

Christmas had not always been so sumptuous. Twice we fled to Mexico under the threat of government raids — "polygamist roundups," the journalists called them. On a night before I was born, to avoid a raid, the children crowded beside their mothers in the back of a delivery van stacked with household goods, which left gigantic bruises as the items slid into soft flesh during the three-day trip along bumpy highways and muddy roads to the deserts of Chihuahua, Mexico. Our father had been born in Colonia Dublan, where his parents had emigrated in order to enter plural marriage after The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS) abolished polygamy in 1890. So our escape to Mexico meant our father's return to his birthplace.

During the family's first exile to the Mexico desert in 1947, in a place called Las Parceles, they lived in tents that sheltered the occasional tarantula and rattlesnake on a parcel of land owned by one Dayer LeBaron. A megalomaniacal clan leader, LeBaron had written my father sympathetic letters when he was imprisoned, inviting him to bring his family to live the Principle without interference from the law. He didn't mention that there'd be no food beyond the yield of a small garden, no lodging, no utilities, only miles of sand and constant wind. The mothers couldn't keep the children's bellies from shrinking.

Still, at Christmas, they drew on wellsprings of creativity. From a broken broomstick my mother sawed 24 disks; half she colored with black crayon melted into the wood, the other half she dyed red with onion skins. Then she fashioned a checkerboard from a square of cardboard. This inspired my father to carve a set of chess pieces from mesquite for his older children and strings of tiny wooden beads with pendants for his wives. The mothers made dried apple dolls for the girls and tore an old sheet to make handkerchiefs with whipstitched hems for my father and the older boys. For the little boys, they made trucks and cars from chunks of two-by-four, with broomstick disks for wheels.

About 6 o'clock Christmas morning, someone saw headlights. This was our father's legal wife, the only one who could stay in Salt Lake City. She took time off from her job as a legal secretary and drove for three nights and two days with her infant son, rolling up to the cluster of tents with cornflakes and molasses and Christmas oranges. They rejoiced, as they'd been subsisting on a bumper crop of yams for two months.

We returned from Mexico a second time, in 1955, but the raids did not abate, and we were forced to live permanently in far-flung, separate homes. My father drove from Utah to Wyoming to Idaho to Oregon to Nevada and New Mexico, visiting each family once every two months. In the winter he braved snowstorms to deliver Christmas provisions: nuts, oranges, flour, and sugar. He'd also minister to our accumulated illnesses, and try to squeeze in a day of hunting or fishing with his sons and dispense some fatherly advice or discipline. If possible, he'd attend our athletic events and music recitals, sitting in the back, incognito. From the stage, when I'd see him clapping, it pained me not to be able to acknowledge our relationship for fear of risking our family's solidarity. During these visits, our father also managed to fulfill his conjugal duties, as evidenced by wives who subsequently grew big with child.

By 1958, my father had been in hiding for three years — he couldn't keep his office open, so each of the mothers had to work. My mother gave piano lessons; her twin sister, Emma, who lived with us and was also married to our father, worked as a waitress in a casino coffee shop. One day a goodwill sack arrived from my father containing a black velvet skirt and vest and a white satin blouse. Aunt Emma wore these to a Christmas party with friends from work. Beforehand, she'd put on bright red lipstick while my mother styled her hair in a shiny braid. And as I looked from her to my mother, in her faded housedress — eczema splotching her hands and arms from cleaning with harsh soaps — I felt that my mother was Cinderella, made to stay home from the ball.

Thus began the Christmases of comparisons, of wondering whether we got more or less — time with my father, gifts, money — than the other families. When we had all lived together under our father's blanket of love, we shared everything. But separated, we became frightened and calculating. Christmas didn't feel right without our father.

We never again lived together on our family compound in Utah. Although my father was able to reestablish his medical practice, his attempt to bring his families home drew threats from law enforcement, so he established four of his seven wives in single-family dwellings across the Salt Lake Valley, while two of the families lived with fellow fundamentalists on a ranch in Montana. His sixth plural wife, discouraged by life on the run, returned to her brother, Rulon Jeffs (father of the recently convicted polygamist Warren Jeffs), who was in line to become the leader of the burgeoning fundamentalist group in Colorado City. Her children had been some of my favorite playmates, but after they merged with the "Crickers" (from Short Creek, pronounced "Crick," before the town's name was changed to Colorado City), they were not allowed to speak to us. We also felt the pain of divorce when Aunt Adah chose to leave all of us, taking her three children with her.

And then, in 1974, my father's youngest wife proclaimed that Christmas was a pagan holiday. She stopped putting up a tree and forbade the exchange of gifts. Two days before Christmas, she held a grand supper to celebrate the birthday of the LDS church founder, Joseph Smith Jr. Under considerable pressure, my father asked his other wives to follow suit but was met with cold shoulders at every household.

Ultimately, I did not choose to follow in my parents' footsteps. My mother's battle with depression, combined with a claustrophobic sense that I couldn't be myself in the fundamentalist group, encouraged me to find my own way. I hated to disappoint my father, but I felt I'd make a poor plural wife, and I refused to subject my own children to the terror I had experienced. At 18, I married monogamously. My husband and I had three girls and a boy, whom we raised mostly in Utah.

But I always stayed in touch with my paternal family. My father showed up for my daughter's first Christmases, having acted as father figure to her while my husband served in Vietnam. My father sang the same songs, told the same stories, and played the same games with her as he had with his own children — 48 at final count. Then in 1977, when my father was 71, two women barged into his office and emptied a .25 caliber pistol into his neck and chest, killing him instantly. They'd acted on orders from Ervil LeBaron, the son of Dayer, from Las Parceles, Mexico. Ervil had decided he should be the supreme religious leader in the world, topping the Pope and the LDS church president. My father was high on a long list of people, including John F. Kennedy and Elvis Presley, that LeBaron had marked for death.

When my father died, everyone grieved desperately, despite the injunction that there should be no tears at the passing of a good man. My daughter dreamed about him for years. From these dreams, she says, she received the guidance to get an education that would allow her to carry on his work of healing the sick and birthing babies.

A few years after my father died, a couple in my neighborhood, aware of my relationship to a polygamous family and suspecting how desperate their lives had become (given that the patriarch had died and that the community did not believe in welfare), asked me to receive some donations on behalf of those in need. So on Christmas Eve, they filled my van with frozen turkeys and hams, fruit, nuts, and candy. Then I began my visits, thinking of those Christmas Eves of long ago when my father delivered food to his scattered families. I stocked bare refrigerators for my sisters, who made a living by cleaning other people's homes. And in so doing, I celebrated the legacies of my family: commitment, faith, tradition.

By then I knew that, despite the pain and confusion of growing up as I did, my childhood had been happier than most. And I am still grateful to be part of this huge, peculiar, loving family, especially at Christmas.