Once I Was Homeless, Now I Advise Silicon Valley

Maisha Leek shares how challenging childhood events steered her toward the big leagues.

I was 14 when I was kicked out of my house. I’d never been in trouble; I was an honor student at Philadelphia’s esteemed George Washington Carver High School of Engineering and Science. But in the years following my parents’ breakup, my charmed upbringing devolved into one that included social workers and even a summer living in a homeless shelter. And then one random day, my guidance counselor called me into his office. He said my family had called and going home wasn’t an option.

That evening, I was held in a teen shelter in Philadelphia. I didn’t even get to say goodbye to my three siblings. I slept in a large room lined with beds and full of girls. My period came that night; I told the woman watching us, who helped me change my sheets, and started to cry nonstop. She repeated, “It’s okay.” It wasn’t though; the rapid loss of control, dignity, and privacy weighed on me. The next day, they sent me to a group home for troubled teens. A nurse performed a physical, checking my weight and height and testing my blood for drugs. There were couches and TVs throughout the mini-motel–style buildings on campus—perhaps to distract us from memories of what brought us together—but you never really forgot where you were. The kids in line with trays at lunchtime, like a scene in a Dickens novel, gave it away.

That evening, I was held in a teen shelter in Philadelphia. I didn’t even get to say goodbye to my to my three siblings.

Initially, I stayed quiet, watching the other teens—and the staffers, who I quickly learned were also watching me. They didn’t give privileges to new intakes, they said, adding I could be suicidal, violent, or try to run away. During one of my first days at the on-campus school (a term I use loosely since it was really a space with desks and tutors who spent the bulk of their time disciplining kids’ violent behavior) another teen in the shelter leaned over during class and whispered, “You don’t belong here.”

He was right; I had to make a plan.

During one of my first days at the on-campus school another teen in the shelter leaned over during class and whispered, “You don’t belong here.”

A few kids from the home were approved to attend Radnor High School, a top academic program in the state. Approval to attend required months of observation, even if you had never shown a single sign of bad behavior. I couldn’t wait that long; school was my ticket to college, which was my ticket to a different life. But my big vocabulary made some of the staffers think I was a snob, and at first, they didn’t seem to want to help me. There will always be people in life who stand in your way if you ask for more than they think you deserve. So I hustled, pleading with my social worker and the staffers to speed up my timeline. In two months, I got approved to go to Radnor.

Former vice president Joe Biden, Trinity Washington University president Patricia McGuire, the author, and Jill Biden.

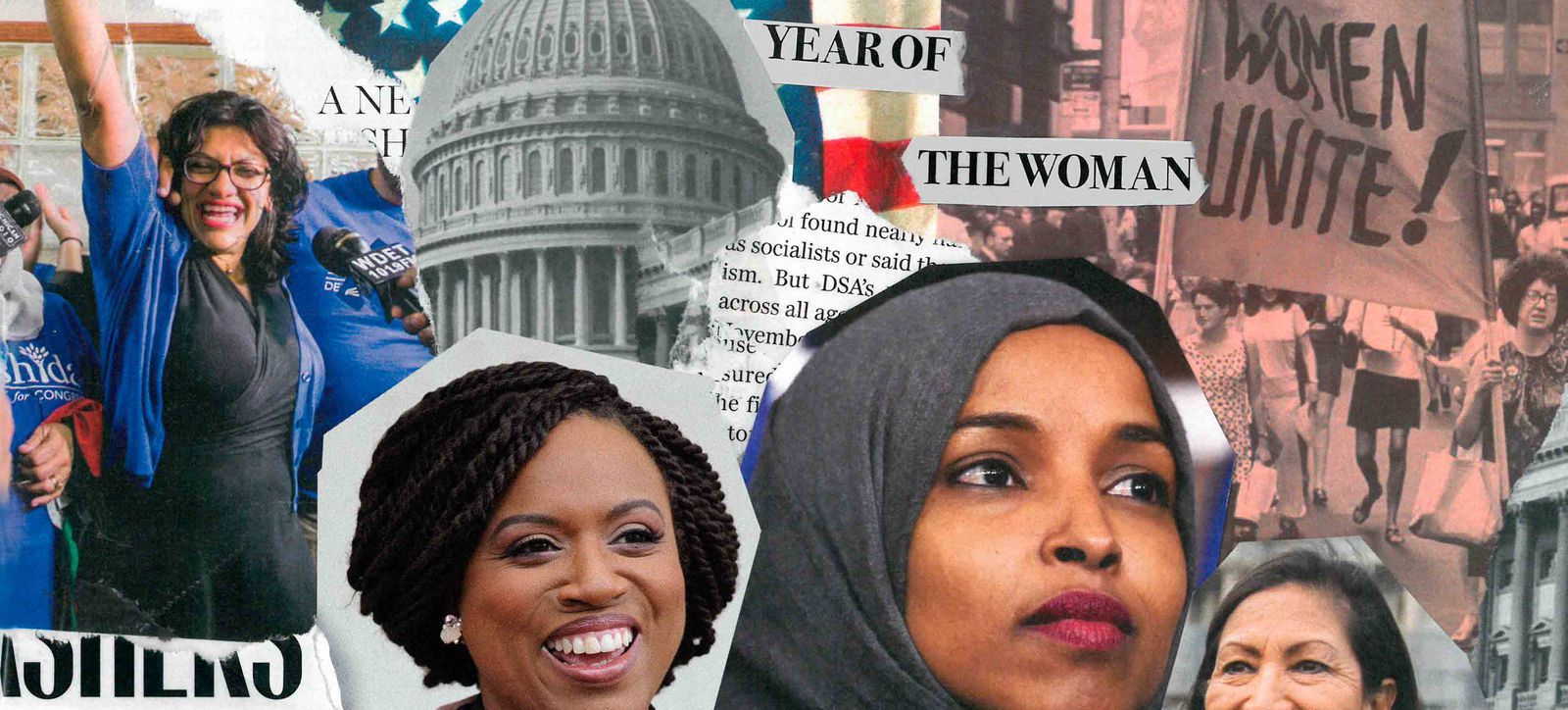

There, with hard work, I found my footing. I eventually left the home and was reunited with my siblings and paternal grandmother. I won a scholarship to Trinity Washington University, worked my way through college, interned at Emily’s List, and completed graduate degrees from University of Pennsylvania and Harvard. In 2010, I served as one of the youngest chiefs of staff in Congress, and I’ve worked with companies including Andreessen Horowitz and Alphabet.

Now I know that difficult situations make us strong. And that strength? It helps you to keep moving forward and focus your mind to create real change.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

This article originally appeared in the February 2019 issue of Marie Claire.

RELATED STORY