The Women Fighting to Save the World

These changemakers—teens and septuagenarians alike—are putting in the work to right our environmental wrongs before it's too late.

From left: Rachel Lee, Mariana Vargas, Sena Wazer, Ayisha Siddiqa, and Alexandria Villaseñor.

As of 2019, the world could no longer deny we are in a climate crisis. It was the year we said enough is enough. Greta Thunberg became the embodiment of our outrage when she said, “How dare you!” to world leaders. I am confident that this year we will turn the corner. We have the climate solutions, and they come with endless benefits, from safer drinking water to more bike paths to new green jobs. We have work to do, but I know we can do it. We have to. Because climate change isn’t about just polar bears, remote locations, or the distant future. It’s about us, our families, our friends, and our health—today. This is the year we start winning the battle.

—Gina McCarthy, president and CEO of NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council) and former administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

These five young people have turned their fears of a warming planet into action and gotten the world’s attention in the process. By Cady Drell

Climate Crusader Greta Thunberg isn’t powerful in spite of her youth; the Swedish 17-year-old’s message resonates so deeply precisely because she is so young. And she’s not alone. Women and girls around the world, plenty of whom haven’t graduated high school yet, are fighting right alongside her, asking everyone to do more to stop the growing threat of a changing planet. Of course, women have been on the front lines of environmental activism for decades: Rachel Carson wrote the groundbreaking 1962 book Silent Spring, which led to federal pesticide regulation; 2004 Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai of Kenya founded Africa’s Green Belt Movement, responsible for the planting of millions of trees on the continent. And then there’s Thunberg herself, the founder of Fridays for Future, a series of weekly strikes demanding government action on climate change. The United Nations estimates that 80 percent of those displaced by climate-change-related disasters are women. Young women in particular will face growing problems associated with a warming world, as many nations (including the U.S.) fail annually to shrink greenhouse-gas emissions. Voters-to-be are understandably scared about the future, but they’re turning that fear into action.

Rachel Lee, 16

“The reason so many young people have found their call to action in the climate crisis is the narrative has shifted from ‘It’s affecting all of us and the earth is going to die’ to something more focused on the youth,” says Rachel Lee, 16, the co–head coordinator of Zero Hour NYC, a youth climate-action collective.

While their specific interests and approaches may differ, many of these environmental activists share a common goal: government action. Sena Wazer, a Connecticut native, has been fighting for cleaner oceans since she was five and her parents read her a book about whales. Lately, the 16-year-old, already a college sophomore, has been organizing rallies to push her state’s governor, Ned Lamont, to declare a climate emergency—and she wants to see other young people put pressure on their representatives. “I think [legislators] need to know that their constituents care,” she says. “I do find a lot of times that politicians are like, ‘Oh, thank you for caring,’ and then they don’t do anything. We expect action, and we’re going to push them to take action.”

Sena Wazer, 16

New Yorker Alexandria Villaseñor, 14, was visiting Northern California in 2018 when the deadly Camp Fire broke out. She feared the effects of bad air quality on her asthma, especially as wildfires become more frequent with worsening climate conditions. She heard Greta Thunberg speak at a climate-change conference later that year, spurring her to go on strike weekly for more than a year as part of the Fridays for Future movement. Strikes are a way for even those too young to vote to challenge the status quo. “When we disrupt the system, we have this amazing opportunity; we end up breaking it so we can make it even better,” she says. “It’s one of the best ways that I can really have a say in the future that I’m being given.”

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Alexandria Villaseñor, 14

A main reason these young women want their governments to act is they understand that, by solving the climate crisis, many marginalized communities will be lifted up too. Ayisha Siddiqa, 21, is the founder of Extinction Rebellion Universities, the collegiate action arm of the environmental group Extinction Rebellion. Her family farmed in Pakistan before coming to the U.S., and she credits that history with her concern for the environment. “When older people say this is not an emergency, it’s because we’ve stopped regarding the people who face the effects of climate change as humans,” she says. “If this crisis affected America first, it would be solved or in the process of being solved.”

Ayisha Siddiqa, 21

“Women are more empathetic and able to comprehend the negative effects climate change has on issues like gender inequality and unequal distribution of resources,” says Mariana Vargas, 20, who works with the Alliance for Climate Education. When she attended the High School for Environmental Studies in Manhattan, she petitioned the U.S. Department of Education to include vegan lunch options. “I hope that my activism inspires others to take the initiative to act fast and not wait for politicians to continue to make false promises,” says Vargas, who will return to college in the fall for environmental and urban studies as well as community organizing, “because change doesn’t start with them but with us.”

Mariana Vargas, 20

This environmentalist/lawyer is not afraid to take on the Trump administration. By Chloe Malle

Abigail Dillen

The Benefit (if you can call it that) of D.C.’s current environment-undermining stance is it “has woken people of all generations up,” says Abigail Dillen, president of Earthjustice, the nation’s largest environmental-law organization. “I feel surrounded by people who are more activated, mobilized, and political—and we need civic engagement to counter this administration.” Since 2017, the San Francisco–based organization has filed 136 cases against the Trump government, with about 120 currently on the docket.

Earthjustice’s tagline, “Because the earth needs a good lawyer,” predates Dillen’s tenure as president. (She started in the group’s Bozeman, Montana, office in 2000, protecting wildlands and endangered species like wolves and grizzly bears.) “It resonates because people understand when you’re in trouble, you need a good lawyer,” she says. “And our planet is often in trouble.”

Dillen, 48, anticipates “the most challenging year yet,” thanks to career lobbyists now running the EPA. “We saw the pace and scale of harm really accelerate last year as they were in charge,” she says. But, fortified by Earthjustice’s record—especially blocking President Trump’s attempt to reopen Arctic drilling—she’s ready for the next fight. “We haven’t lost any big cases yet,” she says. “Right now, in a time when we’re arguing over basically what the facts are in the news, the courts are this remaining venue where you can have really fact-based fights about what the future should look like.”

One of the original grassroots activists, she showed city government how attention must be paid to low-income communities. By Chloe Malle

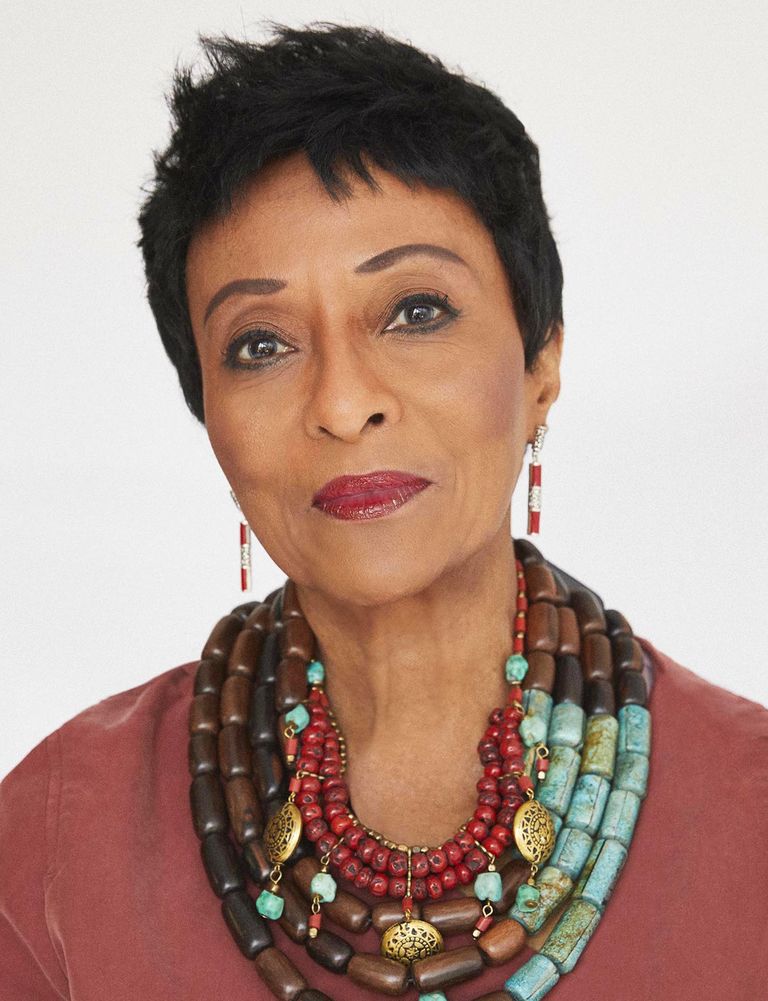

Peggy Shepard

Before "Think Global, act local” was a trendy catchphrase, Peggy Shepard embodied the maxim. In 1988, she cofounded West Harlem Environmental Action (WE ACT for Environmental Justice), the community organization where she continues as executive director and which has made her a pioneer of the environmental-justice movement and grassroots activism. With more than three decades committed to combating the environmental racism that accounts for a disproportionate amount of pollution being concentrated in low-income, often urban, communities of color such as her own, Shepard, 72, has brought attention and action to previously overlooked issues of equity in environmental policy.

After a professional pivot from the media (she was the first black reporter at The Indianapolis News and a lifestyle editor at Redbook and Essence) to politics (she served as public-relations director for Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign), Shepard was encouraged by labor honcho Bill Lynch to run for office herself. She promptly won as Democratic district leader for New York City’s West Harlem, a neighborhood name she invented to reposition her oft-ignored uptown area. It was then that she learned about the new North River sewage treatment plant, located in her district on the West Side Highway at 137th Street. Its noxious odors and emissions were causing illness in local residents, so Shepard took action. Wearing gas masks, she and six others—the so-called “Sewage Seven”—staged a sit-in across the West Side Highway and Riverside Drive. They got arrested, but the act of civil disobedience helped propel their winning lawsuit against the city, earning a $1.1 million settlement plus a $55 million commitment to clean up the plant.

The MTA’s 1988 decision to build a bus depot on 133rd Street across from a housing development and junior high school led to Shepard’s discovery that five of seven bus depots in Manhattan were located uptown (exposing the area to more fumes). Through a lawsuit filed with NRDC against the MTA, WE ACT successfully campaigned for city buses to be converted to hybrids. “We take a lot of credit for that,” she says. “One reason I feel really good about that is so often you think it’s just some little neighborhood community issue. Well, it impacted every bus in the city. It impacted everyone. And, as a community organization, you’re not always able to say that.”

WE ACT focuses on community-based activism and education to battle local insidious environmental hazards and promote initiatives to improve the quality of life for the community’s residents. The West Harlem Piers Park is one such project of which Shepard is particularly proud. “It was a Fairway parking lot,” she says. “I was able to make the case to [then-Mayor] Bloomberg that we had so much of the pollution, we needed some of the benefits.” Shepard was a delegate to the first People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991, which developed the principles of environmental justice, bringing together hundreds of groups from around the country. “That was the first time we realized that this was happening everywhere,” says Shepard flatly. “It’s about values, and to pretend that these issues aren’t values-laden is just to be in denial.”

Outdoor-gear maker Patagonia pioneers “fixing not buying” and gives back—in a big way. By Lindsay Talbot

Rose Marcario

In 2006, Rose Marcario had a midlife crisis. She’d spent years working in private equity and Silicon Valley while also practicing Buddhism—but her personal and professional lives simply didn’t align. “I just couldn’t go on being part of a system that was all about making a few shareholders really rich,” she says. So Marcario quit and went on a meditation retreat in India. “It was an Eat, Pray, Love moment—minus the eating and love parts.”

After several months, Marcario headed back to California. She needed to find a company to run—one that fit her values. Then she heard Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard was looking for a CFO. She’d always admired him and thought Patagonia seemed about as close as one could get to a truly conscious clothing company. The two hit it off, and Marcario joined the company in 2008, taking over as president and CEO in 2014. “Yvon was there during the Santa Barbara oil spill, which is what inspired the first Earth Day 50 years ago,” she explains. “He walked beaches covered in oil. It’s part of his belief that Patagonia has to pave the way for progress on this planet.”

And indeed, the company has done so: While making high-quality outdoor products designed to last a lifetime, it became the first company to start using exclusively organic cotton (in 1996) and the first to make fleece from recycled bottles (in 1993). It’s been donating to grassroots organizations for 35 years (to date, giving more than $110 million to nonprofits), it has fought for the protection of public lands (and is currently suing Trump), and it set a new bar for transparency and traceability in manufacturing. Today, more than 80 percent of the company’s products use renewable or recycled materials. (It expects to hit 100 percent within five years.) It will not use any virgin petroleum sources in products by 2025. That year, Patagonia also plans to be completely carbon neutral—not just in its offices and factories but throughout its entire global supply chain, which it’s achieving by investing in clean energy and carbon capture.

“Our business has more than quadrupled in the last six years. We’ve given more [away] to environmental causes and yet have still been more profitable,” says Marcario, 55, who grew up on Staten Island and cherishes memories of camping trips to the Adirondacks. Nowadays, she kayaks, hikes, and spends time in her garden near Patagonia’s Ventura, California, HQ. She does almost all of the above in her patched Patagonia Nano Puff Vest. The company has been repairing clothes for free since the 1970s, and in 2013 it launched Worn Wear, a garment repairing and trade-in program. “The single best thing you can do [for the environment] is keep your clothes longer or fix them.”

Marcario is currently very excited about a new regenerative agriculture certification Patagonia is launching this April because, she says, “chemical agriculture is killing the planet.” So is the fast-fashion industry, which is set to account for a quarter of the world’s annual carbon budget by 2050. Despite the ubiquity of throwaway fashion, “Patagonia is proof that people still care about quality,” she says. “Customers are starting to demand environmental responsibility. I wish corporate boards were demanding it a little more.”

Shoot styled by Sara Holzman. This story appeared in the April 2020 issue of Marie Claire.

RELATED STORIES

Marie Claire is committed to celebrating the richness and scope of women's lives. We're known for our award-winning features, thoughtful essays and op-eds, deep commitment to sustainable fashion, and buzzy interviews and reviews. Reaching millions of women every month, MarieClaire.com is an internationally recognized destination for celebrity news, fashion trends, beauty recommendations, and renowned investigative packages.