On 9/11, Gulnara Samoilova Watched the South Tower Collapse Through Her Camera

A seasoned photojournalist, Samoilova's instincts were to run towards the scene. Looking back 20 years later, she might not have made the same decision.

Click here to read the complete "Reporting in Real Time" series

Twenty years ago, September 11, 2001 became—and will forever be—one of the biggest and most important news days in American history. As we remember the events that unfolded and honor the nearly 3,000 lives lost, Marie Claire asked five women journalists to reflect on covering the 9/11 attacks in real time and the lessons that can be learned today. Here, former Associated Press staff photo editor Gulnara Samoilova recounts the horror of running to Ground Zero with her camera in hand and watching the South Tower collapse through her viewfinder. Find out how she captured her award-winning photographs of the day, below, then read the rest of the journalists' stories here.

On September 11, 2001, I didn't have to go to work until noon, so I was sleeping at home until I woke up from all the sirens. I lived four blocks away from the World Trade Center, and my apartment building was right next to a hospital, a police plaza, and a fire station, so it was just sirens nonstop. I was like, is something going on? I turn on the TV, I believe it was CNN, and I see on the screen that one of the towers is on fire. The smoke was billowing, and nobody really knew what was happening yet.

As I'm watching it on TV, I see the second plane approach and hit the South Tower. I heard it at the same time because I lived so close. It was surreal. I caught myself thinking the plane is going to just fly out of the building. Then it became obvious that it was intentional. So I got up and put some clothes on. I ran around the apartment thinking, what do I need to take? I had all of this film in the refrigerator, so I threw it in my camera bag. Do I need a flash? It was early morning with no cloud in sight. Then I started running toward the World Trade Center.

Gulnara Samoilova

I got there quite soon and they hadn't barricaded the area yet. I stopped by the Millennium Hilton Hotel so I could have a view of the towers and the people who were coming out from the World Trade Center all burned and injured. I decided to focus on people because that's what I've been photographing all my life. I remember a police officer came over to me and was like, "How can you photograph?" And I said, "Well, I have to photograph. It's for the history."

It was amazing to see all the people from the hotel bringing out the doors to use as stretchers, and all the sheets. Seeing two priests from a nearby church comforting people. Police officers and firefighters...everybody's working and collecting evidence and talking to people. [At this point], there was no communication [with the Associated Press] yet because the cell towers were on top of the World Trade Center, so my cell phone was not working.

The most terrifying and memorable thing for me was seeing people jumping off the buildings. I couldn't even lift my camera. I'm a very visual person, and I was imagining what it was like to be inside of this building and how bad it must have been for them to choose to jump. Exactly a year before, I went to the top of the World Trade Center to the observation deck to see how high it was because I was thinking about doing skydiving. [Looking down], the cars are small. You can't see people. I got scared and changed my mind, so I never did the skydiving. I was just imagining [these people] looking down and that haunted me for a long time.

I was standing right across the street [from the towers] when I heard a noise and lifted my camera. I saw in the viewfinder the South Tower collapsing. I took one photo of the beginning of the collapse and somebody screamed "Run!" so we all started running. I remember I fell and that's the first time I was really scared because I thought people were going to run over me.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

There was nowhere to hide, so I [crouched] behind a parked car. I looked behind me and saw this humongous cloud approaching and it just covered all of us. It was so thick. The air was sharp. It was pitch dark. I started losing my breath. I couldn't hear anything. I think I temporarily lost hearing when the building collapsed because it was so loud. Because I didn't hear any sound, I thought I was buried alive.

I was wearing a T-shirt and I covered my face so the dust wouldn't go into my nose and mouth. I had these weird thoughts, too, (I think my brain was just trying to protect me) like, somebody's going to see my bra because I lifted my T-shirt. Then when I started choking, I heard a voice next to me. I couldn't see them, but it was a male. He said, "Are you okay?" Then I slowly started seeing this flashing light from parked emergency vehicles as well as silhouettes. That's when I realized that I was alive. So I started taking pictures again like nothing happened to me. I took one shot and my film ended so I changed my film and my lens. I was watching everything through the viewfinder, like it was a horror movie.

At the time, I had been a photographer for 20 years, so I could take pictures with my eyes closed. So I guess when I was changing my lens and the film, I probably covered the camera with my hands and that's why the dust didn't come in. But there was dust outside of the lens, which I was wiping off with my T-shirt. In pictures, you can see it's quite dusty and grainy. The whole time I took maybe 100 shots only (about two-and-a-half rolls). I don't remember taking my award-winning photos. I was just on auto pilot. Eventually, somebody gave me a mask and a bottle of water, then I started walking home.

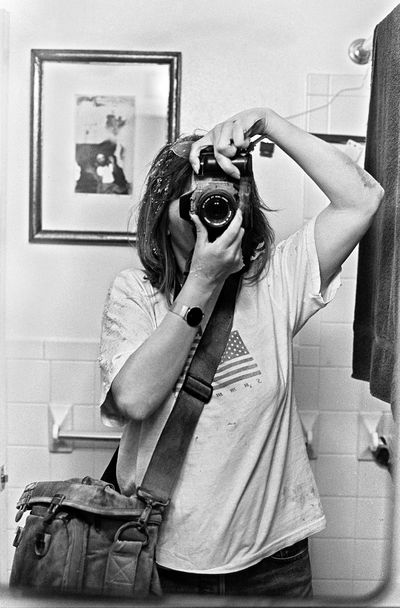

When I got home, I started [developing the photos]. I had a dark room in the kitchen, but because it was during the day, I had to develop the film in the bathroom because it didn't have any windows, so it was the darkest room I had. That's when I noticed I had two black and white [film rolls] and one color. I didn't take color photos at the time; I don't know how it got in my bag. I almost developed [that roll] as a black and white, but I guess I had enough presence of mind to see the different canister color (it was red; the black and white was yellow). [To develop the photos], I mixed the chemicals, then I put them in ice buckets so it cools down to the right temperature.

A self-portrait of Samoilova in her apartment after documenting the South Tower collapse.

While I was developing [the film], the second building collapsed and all the dust came into my apartment. That's when a friend at AP who was a photo editor got through to me on my home phone. She was like, "We all were scared for you. You didn't answer. Are you okay?" I told her that I covered the World Trade Center and the collapse and everything. I remember her screaming, "Gulnara was there!" And [another] editor [in the background] was like, "Get to the office. Get here ASAP." At the time, AP was at Rockefeller Center and there was no transportation because the subway was closed. But another editor, Madge, was living in Stuyvesant Town. So they called me back and told me to go to her apartment, which was closer.

I had my film wet in the tank [developing], and I just started walking there. When I got there, we were drying the film in front of a fan. I was still covered in dust—I didn't have time to shower. Madge gave me this anti-stress tea. I brought plastic film sleeves with me, and I cut the film into strips that had six negatives each, and I put them in a sleeve. Then AP called and said, "Now get to Rockefeller Center." I don't know why. Maybe the scanner wasn't working. I don't remember.

There were buses running, so we got to AP and [senior editor] Vin Alabiso and [deputy executive photo editor] Sally Stapleton were there. Vin looked at my film and he's like, "Black and white?" Because at the time AP only shot color [and I shot in black and white for my personal work]. I think every news organization shot in color only and I said, "I have a roll of color as well, and I think I got the tower collapsing in it." So we called the Time & Life building, which was around the corner, and I knew that they had a lab, so we went there and developed the film. I waited until it dried and I went back to AP. Vin and Sally were looking at my film through the loop in a light box, and they were chopping my negatives one by one. Then I sat at the desk and scanned my own film and other photographers' film. I just kept myself busy working.

My fiancé was in Jersey City and I think he picked me up [from the office that night]. I don't remember getting to Jersey City at all. I just remember at night I had friends calling me (the cell phones were working in Jersey City). Then in the morning my boss [called and] woke me up and he's like, "Get back to the office." My body hurt so much. It felt like a truck ran over me. I was like, "Can I take the day off? I can't even move." He's like, "Please get to the office." So I got to the office and he showed me all of these newspapers online and offline that had my pictures in it. The AP put my photos on the wire, so they were all over the world.

Samoilova's award-winning photo, which captures survivors covered in dust and debris after the collapse of the Twin Towers.

My most powerful photo, which won first prize from the World Press Photo, I shot in black and white. It was published everywhere. It wasn't on a lot of covers because it was black and white, but several newspapers chose to put it on the front-page even though it was black and white. I read stories that some editors deliberately chose to put it on the front cover without telling their bosses. The head of the Moscow AP bureau published [something important] in black and white to support me. Because [the photo] was published in so many publications, it became okay moving forward for a lot of publications to start publishing in black and white.

I wasn't even supposed to be in New York on 9/11. I had a ticket to fly back to Russia [where I grew up] on September 8 because of a longterm documentary project that I was doing at the time, but [I had to cancel]. I didn't fly, and I still have the ticket.

[The trauma and stress of the day] was really tough at the time. But it wasn't only September 11 itself. I was a photo editor of special projects and for a year I was looking at everything that staff photographers and freelancers did around September 11 for contests, exhibitions, and books. I've seen photos that nobody saw, and it was even more traumatizing. I was crying almost every day looking at those photos. I was really suffering from PTSD for a long time, and I went through more personal challenges. I broke up with my fiancé. So I quit AP after a year. I just couldn't handle it anymore. I had enough. Looking back on that day, if I could do it all over again, I don't think I would have gone [to Ground Zero].

[Later on, I participated in] a research study done by Columbia University on PTSD. I was working with two professors every day for two weeks and I had to talk about 9/11 as if it was happening in the present moment. They were video taping me. Then they would give me the audio tape, I would listen to myself talking about it, and then they would give me exercises. I had a fear of going to [tall] buildings, like the Empire State Building, because I was scared there was going to be another terrorist attack. I had nightmares of a building collapsing and I couldn't get out and then I was jumping off the building. Then I made a conscious choice to get past it. In 2012, I moved back downtown. I had a view of the new World Trade Center [going up]. For me, it was like a middle finger to the terrorists.

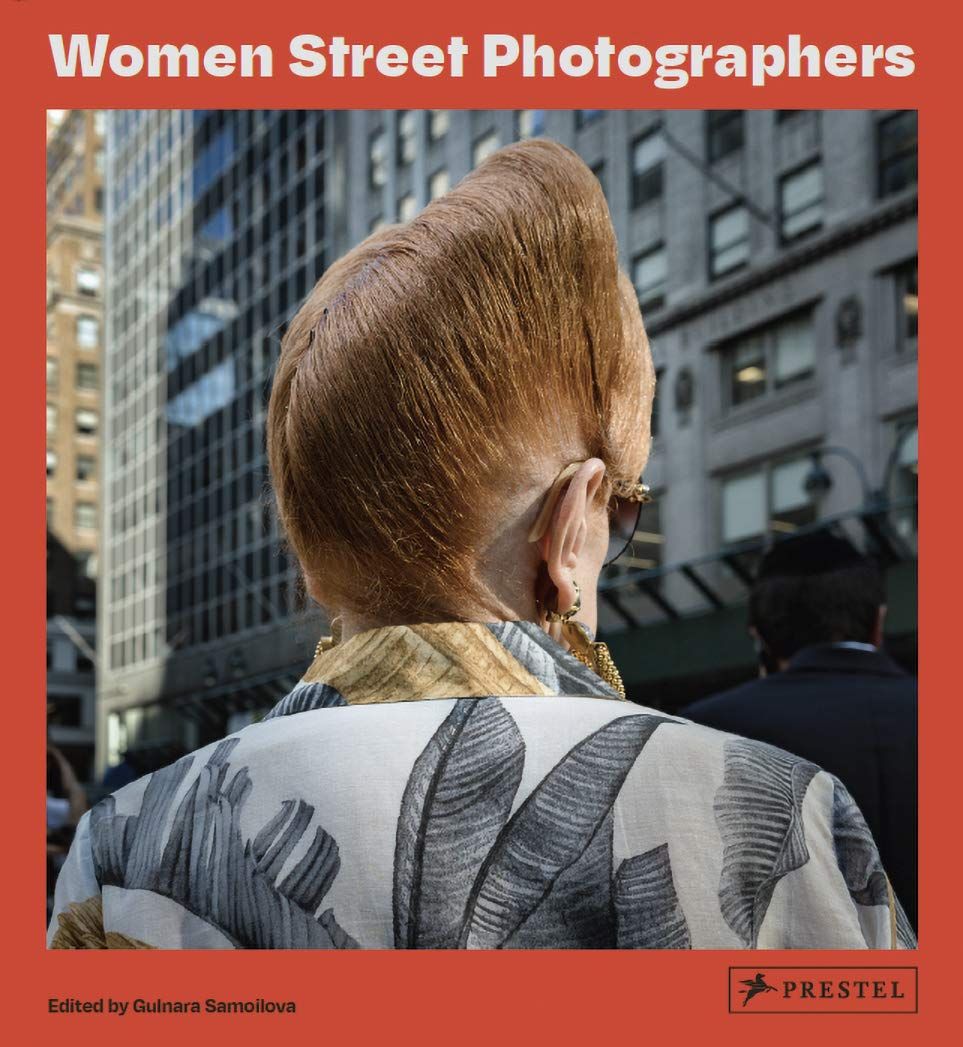

It took me a long time to pick up a camera again. I didn't take pictures for several years. I've been a photographer for 40 years now. I had my own challenges, but photography is my passion. I can't just stop taking pictures or being in the photography field. After I quit AP, I started my own business with documentary-style photojournalistic wedding photography. I did that for a while and now I'm founder and curator of Women Street Photographers. I will always be in photography and nothing will stop me from continuing my passion.

When the pandemic started, my old instinct of being a photojournalist [kicked in] and I was like, I've got to go outside and just document. I was so confused. I wanted to go out and document and yet I was so scared. I was working on my book. I'm like I need to be healthy, I need to live to finish this important book. Not only for me, but for a lot of women photographers out there. I even called this friend of mine who used to be a war photographer and he was like, "Take care of yourself, it's not worth it." And I listened to him.

I don't regret not going out and risking my life because during the first days [of COVID-19], nobody knew what was happening. Like, can we even breathe this air? To me it was almost as powerful as 9/11. But on 9/11 I knew there was a terrorist attack; there's a building on fire. I could see it. But you don't see the virus. When you don't know what's happening, there's more fear.

As I said on 9/11 to the police officer, my job was to document. His job was his job. The firefighters' job was to go into this burning building. The medical personnel's job was to take care of the injured. I had to tell myself there are professionals who are reporting right now because it's their job. My job right now is to stay inside, listen to the mayor, and I did.

RELATED STORY

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.