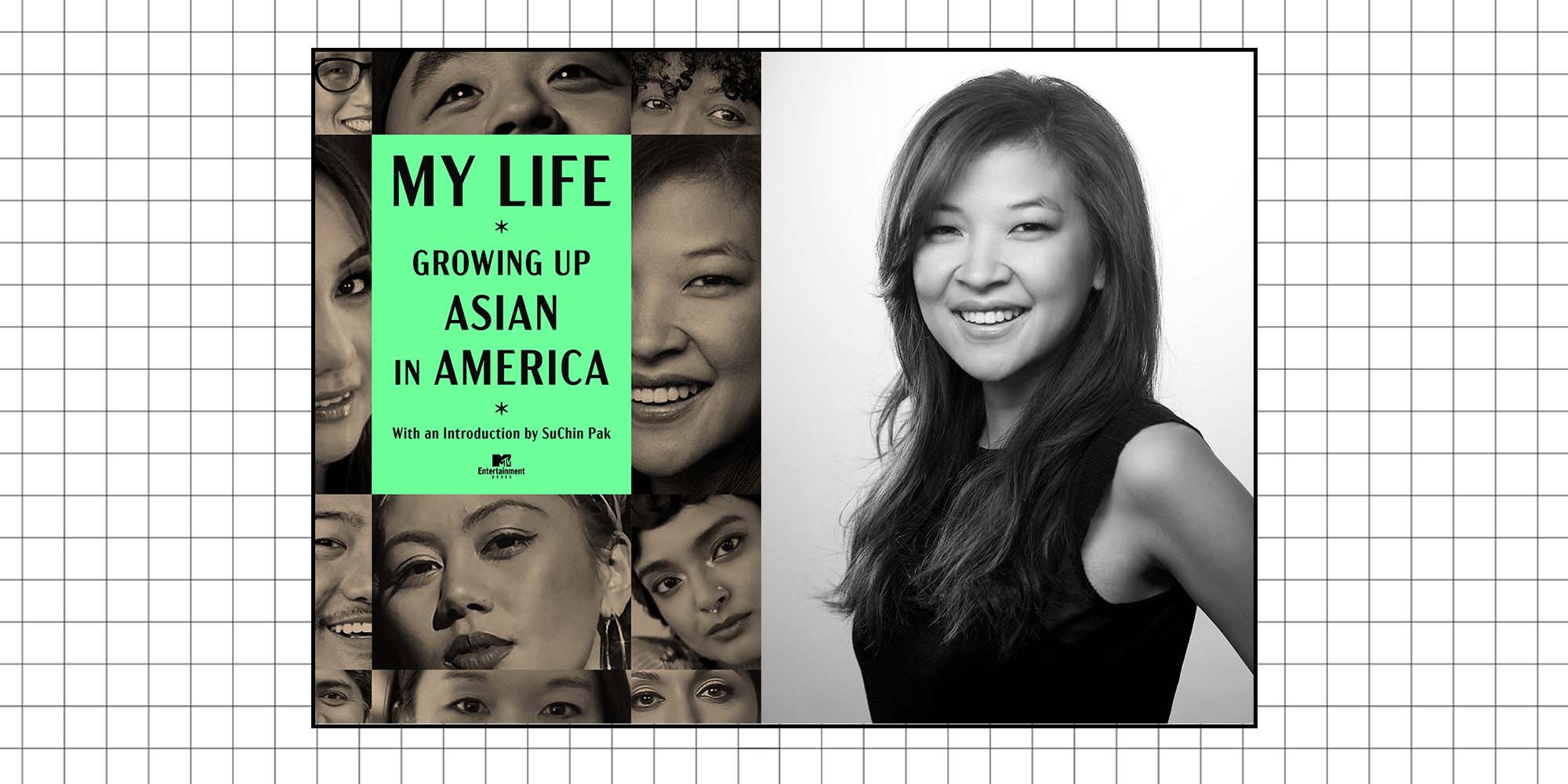

SuChin Pak Is No Longer Settling for Your Definition of Courage

In an excerpt from a new book, the journalist details the racist incidents at MTV News that shaped her early career and how she's only recently been able to dismantle that trauma.

SuChin Pak, 45, has spent more than two decades in the spotlight, which also means, as an Asian American, she's faced nearly as much time battling racism in the public sphere—most notably during her tenure as an MTV News reporter in the early '00s. In the foreword of the new book, My Life: Growing Up Asian in America, Pak details those devastating early years in front of the camera, and how racist incidents coupled with internalized xenophobia manifested into debilitating shame and guilt. But in recent years, triggered in part by the wave of hate crimes against the AAPI community, the journalist and current host of the podcast Add to Cart, has been able to examine and dismantle that trauma—ultimately allowing her to rewrite her definition of courage.

The collection of essays, edited by the Coalition of Asian Pacifics in Entertainment and available on May 17, also features stories from 30 other creators—including Ellen K. Pao, Melissa de la Cruz, Amna Nawaz, and Teresa Hsiao—about their singular experiences as an Asian American. And how they, like Pak, must constantly detangle the joys of their heritage from the unfortunate truths of being Asian in America.

When I was a teenager, courage basically meant never saying no. It meant never wanting to miss out on an opportunity and saying yes to things that felt bigger than my own small world. As a high school junior, I said yes to an offer to host a weekly teen show that aired on my local news channel, not knowing then that this would be the biggest turning point of my life. Being a TV journalist wasn’t my dream just yet, because even though I was working on television, I never once thought that I could actually make a living as a journalist. TV reporters looked like Diane Sawyer and Barbara Walters, not sixteen-year-old Korean American girls with frizzy bobs and acne. Yes, I had Connie Chung to look up to, but there was this sense that America had its one Asian American anchor—the job had been filled. I figured I would ride this stroke of luck as far as it would take me, and then my regular plan of becoming a lawyer, like a good Asian daughter, would resume.

Right from the beginning, cameramen told me to “open my eyes” and “squint less.” It was always embarrassing to hear, to have my insecurities about the way I looked—so different from what an American should look like—validated again and again by people I felt had the right to pass this kind of judgment. But if being successful on their show meant adjusting my appearance, I was willing to pay what felt like a small price. Like most Asian American women, I had a lot of training to appear less Asian and more white. I have memories of sitting with my glamorous Korean aunties, who regularly praised how fair my skin was and how beautiful I would be as soon as I could get my eyes done. I have a roll of film from a summer in Hawaii spent with my cousins when I was nine, where in every single shot I am raising my eyebrows as high as they will go, giving me a perpetual look of shock. But my eyes are, indeed, wider. Eventually, I experimented with tape to fold my lids into a rounder shape. I practiced facial exercises that would slim my jaw and open my eyes. I did everything I could to take the cameramen’s “helpful” tips to heart and thanked everyone around me, all the time, for the absolute privilege of the opportunity.

I fell in love with reporting on that job and found a new reserve of courage, this one telling me to chase this dream, to have the courage to say that this is what I wanted for myself. And I convinced myself—and my parents—that I could have a career in journalism. Thankfully, that turned out to be mostly true. My hard work paid off, and in 2001 I landed a job at MTV as a news correspondent, which put me in front of millions of people. I tiptoed around that space, terrified of screwing things up and always feeling like I was holding someone else’s lottery ticket. I found my place in that world by hiding my fear and smiling a lot. I became very adept at making people—even terrible ones—comfortable by using flattery and humor. When I encountered inequality or unfair treatment because I was a woman and/or Asian American, I doubled down on nice or made jokes to defuse the tension. When it was really bad, I remained in what I imagined was dignified silence. I had convinced myself that if I voiced my dissatisfaction or anger, I would be jeopardizing my career. This is the pact so many of us make to fit into a society dominated by white supremacy: If we play by their rules, we get to stay. My strategies would work ... until they didn’t. And then, in those instances, I would crawl into bed and cry and be enraged and spiral into fear.

I felt like a coward all the time. If I could just be the traditional version of courageous—bold, straightforward, forthright—maybe the unbearable weight of unworthiness and shame I was carrying could be lifted. But I didn’t have it in me; I didn’t know how to be that kind of brave. I experienced deep shame whenever someone commented on how “chinky” my eyes were and I said nothing in response. Or when I pretended to take it as a compliment when someone commented on how beautiful all Asian women were. I had been fed a very convincing narrative that if I didn’t, in that moment, confront the racism, that if I ignored the ubiquitous ways Asian women are fetishized all the time, I was to blame. That I had blown things out of proportion. That they hadn’t meant it that way. That I was being overly sensitive.

A couple of years into my time at MTV, my feelings of unworthiness gave way to anger. I was angry all the time—I tried so damn hard to be good, to follow the rules, and none of it seemed to make a difference. Every day I was on air felt like an audition. And everything I did—my mannerisms, what I wore, how my hair was done—was scrutinized by the executives. I constantly felt like I was on borrowed time, that they would replace me the moment they found a better person to fill my seat.

If I could just be the traditional version of courageous—bold, straightforward, forthright—maybe the unbearable weight of unworthiness and shame I was carrying could be lifted.

I hated their version of me, as it rubbed so sharply against the truth of who I knew I wanted to be. But whose fault was that? I had been complicit, hadn’t I? I had let them have so much control over who I was and how I behaved ... and I didn’t know how to be any different. All I knew was, I no longer had it in me to be apologetic, grateful, and polite anymore. But what could I do with this anger? I was afraid if I lost my job, my family would struggle financially and I’d be seen as a failure. I was afraid that I’d never get hired again by another network. I felt no power to change my circumstances, and just as defeating, there was still a big part of me that wanted their acceptance and approval.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

I see now that the shame, anger, and fear I was dealing with at this stage in my life have transformed the way I define courage today. I started to ask myself, What will happen if I stop complying? What will happen if I stop smiling and being nice? It is terrifying to ask these questions, but it’s courageous. The simple awareness that these questions burn inside of us is courageous. I want to acknowledge—no, shout!—that courage can look very different from the image on the poster. It can look like someone who is shaking, crying, and emotionally undone. When I was crying because things felt unjust, when I was shaking with anger but unable to speak because I was still afraid, these are the moments I’ve come into awareness of myself and my worth. Those uncomfortable feelings guide us to an understanding that we deserve more. It was when I wasn’t angry or an emotional wreck that I felt the most disconnected to who I was. In that kind of compliance, I was giving up on myself, giving in to their version of who I should be.

When I think back to all the times I didn’t speak up, all the times I let it slide, every time I had to hide or contour my face to make it more palatable for the cameras, I think about how, alongside the seeds of unworthiness, I was also planting the seeds of this awareness. That’s what I nurture now. I let the most complicated emotions guide me to where the injustice is. For me, this is the most courageous work of all: dismantling and reconciling my former shame and guilt while also honoring them. Every now and then, I watch old footage of myself—smiling, holding in so much emotion but still projecting intelligence and compassion—and I no longer see a coward. I see someone who is using all that she knows to survive, who is bravely navigating a world that doesn’t value her.

From MY LIFE: Growing Up Asian in America by CAPE, the Coalition of Asian Pacifics in Entertainment. Compilation and Introduction copyright © 2022 by Simon & Schuster, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books/MTV Books, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Neha Prakash is Marie Claire's Entertainment Director, where she edits, writes, and ideates culture and current event features with a focus on elevating diverse voices and stories in film and television. She steers and books the brand's print and digital covers as well as oversees the talent and production on MC's video franchises like "How Well Do You Know Your Co-Star?" and flagship events, including the Power Play summit. Since joining the team in early 2020, she's produced entertainment packages about buzzy television shows and films, helped oversee culture SEO content, commissioned op-eds from notable writers, and penned widely-shared celebrity profiles and interviews. She also assists with social coverage around major red carpet events, having conducted celebrity interviews at the Met Gala, Oscars, and Golden Globes. Prior to Marie Claire, she held editor roles at Brides, Glamour, Mashable, and Condé Nast, where she launched the Social News Desk. Her pop culture, breaking news, and fashion coverage has appeared on Vanity Fair, GQ, Allure, Teen Vogue, and Architectural Digest. She earned a masters degree from the Columbia School of Journalism in 2012 and a Bachelor of Arts degree from The Pennsylvania State University in 2010. She lives in Manhattan with her husband and dog, Ghost; she loves matcha lattes, Bollywood movies, and has many hot takes about TV reboots. Follow her on Instagram @nehapk.