The First Crime Against Them Is Rape. The Second Is Being Billed for It

Both federal and state laws say survivors of sexual assault should receive free rape-kit exams. Yet every year in every state for the past two decades, victims have been billed. One year ago, New York announced it had found wrongdoing at seven hospitals. Marie Claire goes behind the scenes of the investigation to tell the story of how one woman—who was billed seven times and sent to collections—spurred a statewide probe that revealed hard truths about our nation’s hopelessly broken system for caring for sexual-assault survivors.

In April 2015, Cate Smithson did what countless women before her have done: She broke up with her boyfriend, packed her belongings in a U-Haul, and hit the road, bound for New York City. In addition to her job as a remote editor for a travel website, she quickly found a side gig waitressing at a restaurant. One night after her shift, her coworkers suggested they go out for drinks. As they were parting ways at the end of the night, the then-27-year-old Smithson started for the subway when one of her new friends said, “Absolutely not! It’s not safe,” and hailed her a cab. To the driver “she was like, ‘Hey, man, take her straight home,’” Smithson recalls. “And that was all he needed to hear.”

Smithson nodded off in the backseat, waking as the driver slowed. “I saw the car’s headlights reflecting off the wall of a parking garage and I immediately knew what was happening,” she says. He told her he had a knife and would “hurt her worse” if she resisted. Then he held her face down and raped her. “I was completely alone. There was no one around. It was like 5 in the morning and I’m in a parking garage and I don’t even know how I got here,” says Smithson. “I didn’t even know how to argue or fight my way out because there was nowhere for me to go.” It was her fifth day living in the city.

After the attack, the cabbie started driving again and Smithson jumped out of the car at a red light. She made it home to her apartment in downtown Brooklyn after getting a ride from a good Samaritan and asked to sleep in her roommate’s bed. When she awoke hours later, she was alone. “I was completely defeated,” she says. “I felt so small, so powerless, and, like, dead.” She willed herself to Google hospitals and found one called the Brooklyn Hospital Center a mile away. She saw some bad reviews but thought, Who reviews a hospital? She told herself, Whatever, it’s a hospital, I’m sure it’s just fine and got in an Uber.

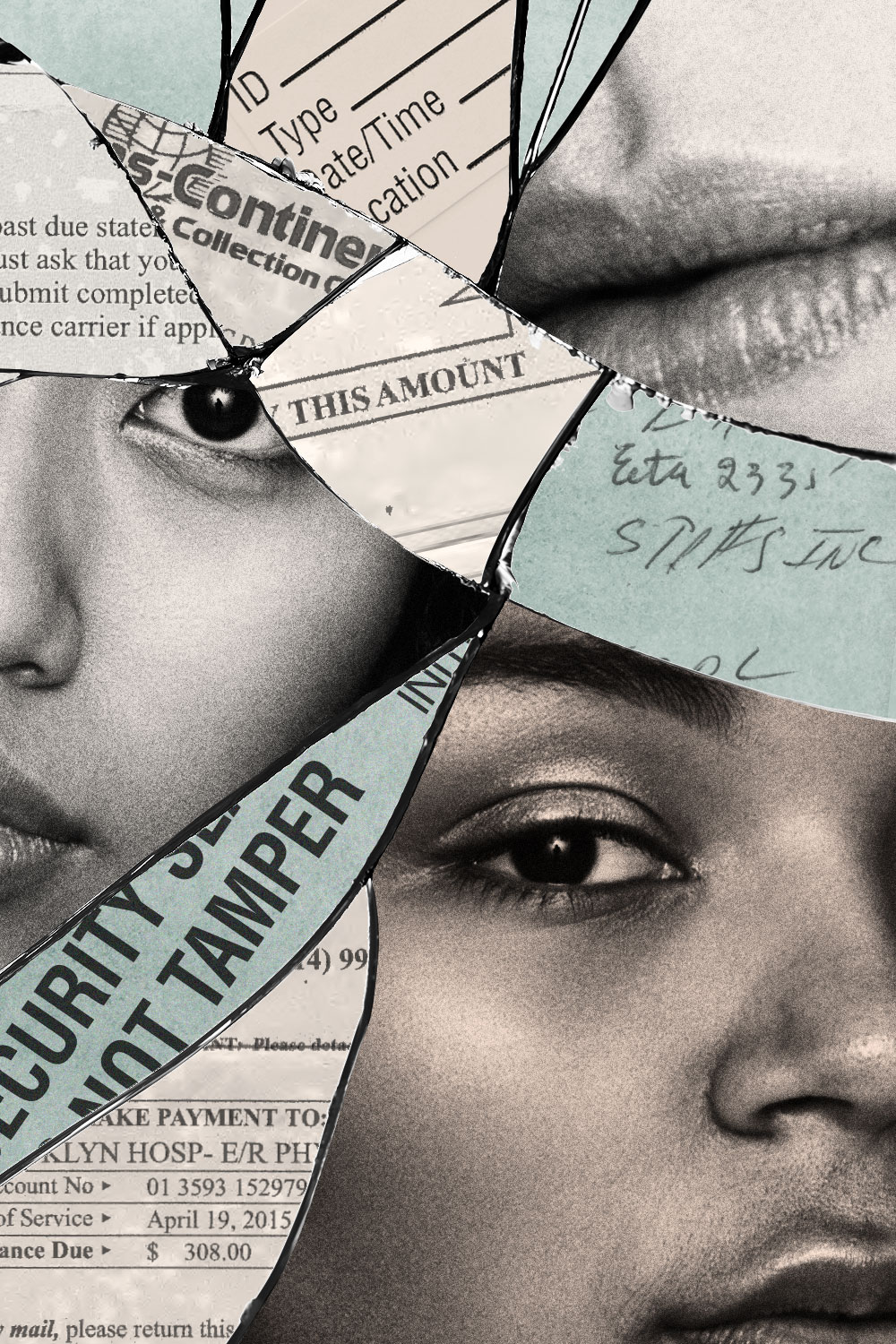

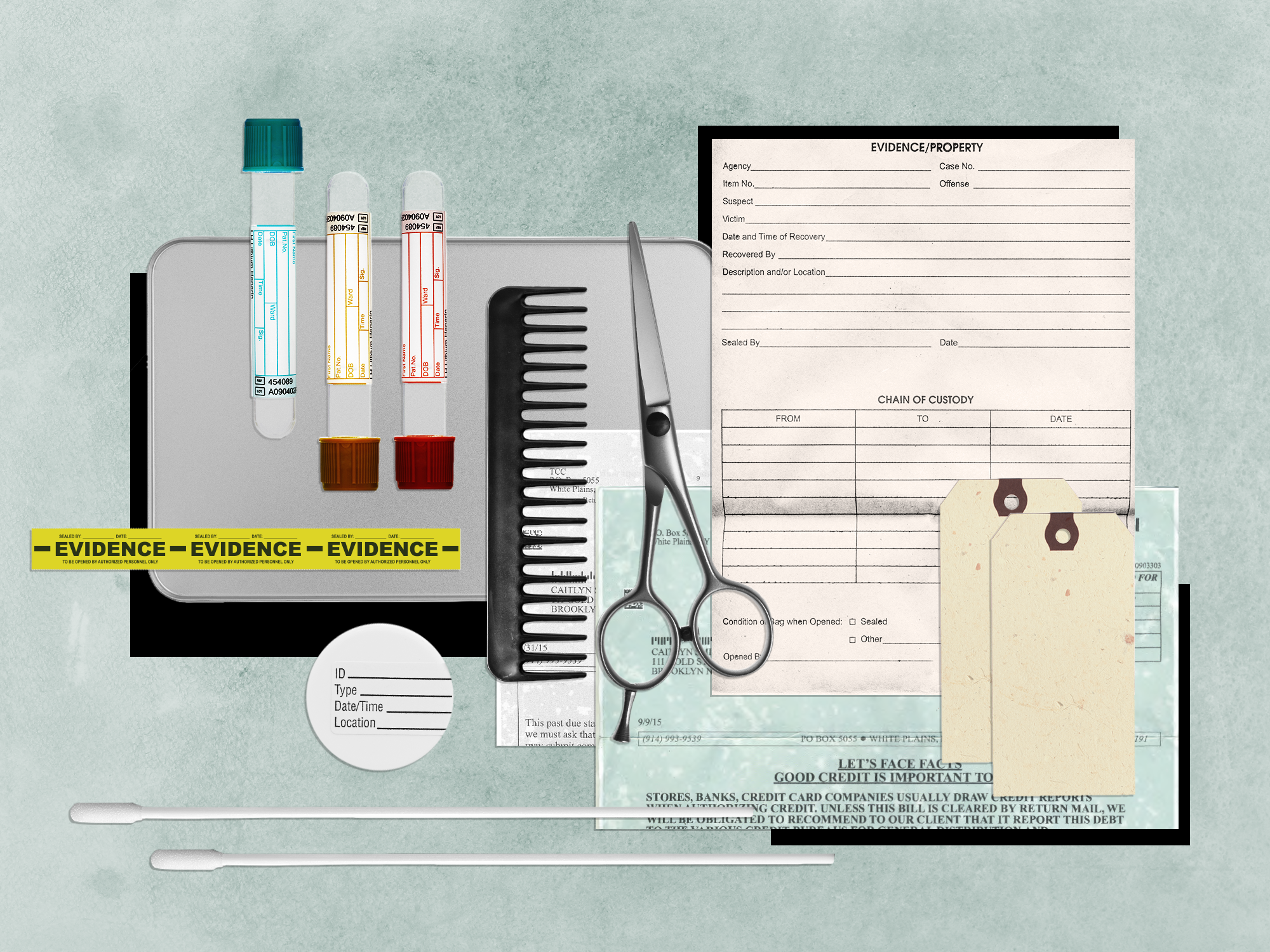

She was there for a sexual-assault forensic exam, known as a rape kit, during which a survivor’s story is documented, she or he is examined and assessed for injuries, and evidence is collected (blood, semen, hair, etc.). Smithson was greeted by a physician and a nurse who “had, as far as I could tell, never conducted a rape kit before,” she says. “They gave me this very clumsy exam. They were reading the instructions off of a folded piece of paper as they collected evidence off of my body.” After the physical exam and a conversation with two police officers, she was given a shot to prevent some sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and sent home with pills to ward off others, along with a dose of the morning-after pill, post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV, and a packet of information. “It was like 10 pages of paperwork that looked kind of confusing, and I was like, I will figure this out later,” Smithson says, noting that she received inadequate follow-up instructions, incorrect contact information, and an insufficient supply of prophylaxis. She remembers seeing a reimbursement form and “didn’t really understand what that was for. I thought maybe it was for if I couldn’t work or something.”

In the days that followed, Smithson worked closely with police officers investigating her case but otherwise tried not to think about her assault. “I wanted to put it behind me,” she says. “Almost immediately after it happened, I was like, how do I erase this? Don’t give it any attention.” That worked pretty well, she says, until about a month later, when a hospital bill arrived.

Rape survivors aren’t supposed to have to pay for the examination performed in the aftermath of an assault. Think of it this way: If your house is robbed, police don’t send you a bill after they dust your home for fingerprints. A rape kit is a much more personal and invasive form of evidence collection, but it is evidence collection all the same.

In 1994, the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) required states to provide free sexual-assault forensic exams in order to be eligible for crime-prevention grants. It was amended in 2005, to clarify that victims don’t have to report the crime to police for the exam to be covered, and again in 2013, to ensure survivors can’t be made to pay out of pocket, even if they will be reimbursed later. VAWA requires that the exam, at minimum, include an assessment of physical trauma, a determination of penetration or force, a patient interview, and swabbing for evidence but leaves it up to states to determine where the money comes from. Thirty-four states use victim compensation funds, 11 draw from law-enforcement or prosecutorial funds, and a handful of others leave it to individual counties to select a funding source, create special funds, or take from their human-services departments, according to a 2014 report by the Urban Institute, the most recent data available.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Every state ostensibly complies with VAWA. A minority go further than the law requires in covering related services. Fifteen states pay for STI testing, 13 cover a pregnancy test, 10 take on the emergency-room and hospital fees, six pay for emergency contraception, five pick up the bill for related injuries, and two fund counseling. And yet, despite federal and state laws, government investigations, and countless media reports uncovering wrongdoing over the years, sexual-assault victims nationwide continue to be routinely and illegally billed for their rape kits.

In some cases, government officials or hospitals willfully defy the law. In 2008, when Sarah Palin was running for vice president, news surfaced that during her time as mayor of Wasilla, Alaska, in 2000, the town openly disregarded a state law preventing victims from being billed for rape kits because of the “burden put on the taxpayer.” In 2014, an investigation by The Times-Picayune found that hospitals across Louisiana were charging victims thousands of dollars for their rape kits because of strict limitations on who could qualify, like requiring patients to file a police report—a direct violation of VAWA. (The state passed two laws the following year to fix the problems.) In 2017, KTHV-11, the CBS affiliate in Little Rock, Arkansas, found it was the policy at at least three area hospitals to bill a patient’s insurance for a rape kit, in defiance of state law.

In many other instances, however, the reason why victims are billed can be chalked up to banal clerical errors—the result of untrained hospital staff who improperly file paperwork, use the wrong billing code, or otherwise fail to correctly identify the patient as a survivor of a crime whose bill should be sent to a victims fund. Chances are, you or a loved one has received at least one erroneous medical bill at some point, so you might have an idea of just how commonly this occurs. That’s the challenge: This wrongdoing is happening on a hospital-by-hospital basis. We already have the necessary laws in place; for once, that’s not the problem. What we don’t have is enough consistency among hospital systems to guarantee rape victims nationwide are treated with the respect and dignity they deserve. Instead, the quality of care you receive often depends on the zip code in which you were raped. And for survivors hounded by hospital bills, it feels like they are being told, “We don’t even care enough about you to file the paperwork correctly.” “It is emblematic of how, as a society, we often don’t take sexual violence seriously enough—how little we appreciate the trauma of sexual violence,” says Jennifer Wyse, a social worker at Safe Horizon, a national victim-assistance nonprofit based in New York City. “This could be one of the worst moments of someone’s life. Their sense of autonomy and bodily integrity is violated. Safety is a basic need we all have. As a society, we definitely need to do better in responding to that.”

Too often, it falls on survivors to do the work. Which is exactly what happened in New York. Most women who are charged for their rape kit just go ahead and pay it, or their insurance picks up the tab. A 2017 study published in the American Journal of Public Health found that in 2013 alone, victims nationwide and their insurance providers paid more than $9 million for medical services related to rape. Of the average total cost of $6,737 per case, 86 percent (or $5,789) was paid by the insurer, while 14 percent (or $948) was paid by the survivor. When the first bill, for $308, the physician’s fee, arrived in Smithson’s mailbox in May, followed by another in June, for $449, the hospital’s fee, her first thought was not, Oh, fuck, I have to pay for this, Smithson says. “I knew I had this paperwork that said something about reimbursement, so I thought I just had to fill it out.”

She started filling out the form but soon realized this form couldn’t be meant for her. It asked her for things she couldn’t know, like the physician’s identification number. So she called the hospital and was batted around from department to department, each time having to tell the stranger on the other end of the line about her rape. Finally, Smithson reached the physician who gave her the exam and tried to explain that she had paperwork that it seemed the doctor needed to fill out. “I’m not exaggerating when I say the doctor hung up on me,” Smithson says. “She just hung up. So that sucked. That super sucked.”

Nevertheless, Smithson persisted. She went to the hospital. “What choice did I have?” she wonders. They asked why she was there, and she said, “I’m back because I let you ding dongs do nothing when I came here a month ago. How can you help me now?” She was again volleyed from person to person until she was “basically just kind of violently crying by myself at the hospital with nobody helping me.”

Finally, someone handed her a pamphlet that said to call Safe Horizon. She made an appointment and met with Jennifer Wyse, who quickly confirmed what Smithson suspected: “You weren’t supposed to have this form. You weren’t even supposed to see it. It’s not for you to worry about,” Wyse told her. Wyse took over for Smithson, calling the hospital on her behalf. She told the hospital that billing Smithson was not okay, that they should have billed the Office of Victim Services (OVS) directly. “But at the end of the day, I can’t force the hospital’s hand,” Wyse says. “I can only keep reminding them, ‘Hey, this is against New York State law’ and ask them to stop.”

Smithson left New York City after six months. “After this happened, I just didn’t feel like it was a place I was going to be okay in,” she says. The bills kept coming, following her to her new home in Seattle like a curse. In the year following her rape, Smithson was billed an additional six times, for the same amounts ($308 and $449), by both the hospital and collections agencies. She and Wyse settled into a maddening routine: The bills would arrive, Smithson would forward them to Wyse, and Wyse would call the hospital, which would tell her the account would be pulled from “self-pay status,” that it would bill OVS, that the bills would stop coming. And then a few weeks, or in some cases several months, later new bills would arrive, starting the process over. “It felt like a fresh defeat every time,” Smithson says. “It felt like I was being made to become smaller and smaller and smaller.”

Every time Smithson spoke to Safe Horizon it reiterated that this is illegal, so “I just thought, If it’s illegal, then I’m not going to have to pay for it. That’s not how this works,” Smithson says. “It wasn’t necessarily that I couldn’t pay. I’m not wealthy, and it might screw up my credit and make me feel like shit, but paying it was not a life-or-death situation. But I was so upset about the principle of it—that these people were making me feel like I had no agency, no resources, no voice. I didn’t feel like anybody cared what happened to me.”

In June 2016, the bills finally stopped coming. But after what they’d been through, Smithson and Wyse wanted more than resolution; they wanted a guarantee no other woman would be billed. “I wanted to blow a whistle and say, ‘This happened in my case, and how do I make this not happen to anybody else?’” Smithson says. “I wanted someone to admit their error so that I had confidence that it was not going to happen again in the future.” (“And it would be really nice if someone said, ‘We’re so sorry. You didn’t deserve this,’” she adds.) So Wyse reached out to another survivor advocacy organization, the New York City Alliance Against Sexual Assault (NYCAASA), for help.

Josie Torielli, then a senior intervention consultant at NYCAASA, was familiar with the problem. She’d helped a few rape victims who were billed over the years. She recalls getting a call in 2015 from a sexual-assault survivor who got a bill for around $400 for a rape kit that was performed 10 years prior. The woman had left New York City after the assault to build a new life in Pennsylvania. “She said to me, ‘I’ve worked so hard to put my life back together, and I feel like I’m right back in that emergency room from 10 years ago, remembering how awful that night was,’” Torielli says. “It really disrupted her capacity to heal. And there are layers here: the trauma of what happened to you and also the trauma of the system failing you. When systems that are set up to take care of you and aid in your healing are actually doing the opposite, that betrayal is really hard.” The woman said she had started therapy again as a result of receiving the bill and was looking into getting medication for anxiety.

Phone calls like that led Torielli to think there had to be more survivors out there. “I thought, How can we advocate for not only this one person but also a system change so no one else has this same experience?” Torielli says. In January 2017, she reached out to a contact in the New York attorney general’s office to see what they could do. During one conversation, Torielli was asked: Do you think this is happening to other people? “And I said, ‘Yeah, I know it is.’”

The AG’s Health Care Bureau was put in charge of the investigation. It was the first time the office had received such a complaint, but the fact that Smithson was billed repeatedly, even after bringing it to the attention of people who should have been able to remedy it, led investigators to believe it was a sign of a larger problem. So the AG’s office began requesting information from the Brooklyn Hospital Center: what policies it had in place, how many patients had received rape kits, and how those people were billed.

Months later, right before Thanksgiving in 2017, Wyse and Smithson got a call from the AG’s office. They were told the investigation had found that the Brooklyn Hospital Center had conducted 86 rape kits between January 2015 and February 2017. By NY law, those patients should have been given the choice to send the bill to OVS or to their health-insurance company. Instead, 85 of those 86 patients either were billed directly or had their bill sent to their insurer without their consent. Thirty-seven patients were improperly billed more than $15,500 for rape kits; seven were sent to collections. “The situation makes me reflect on how many people don’t come through our doors,” Wyse says. Including Smithson, “a total of 85 survivors were billed. What happened to those other 84 people? We don’t know.”

Days later, on November 28, then-AG Eric Schneiderman held a press conference announcing the investigation (which Smithson says felt “really big and gratifying”). The hospital agreed to reimburse all of the patients who paid the bills and pay a $15,000 fine to the state. Going forward, hospital staff agreed to provide a form to patients informing them of their choice to have the state pay for the cost of the exam or to charge their insurance. “This is a systems breakdown. This is not a matter of one or two rogue employees,” Schneiderman told reporters. “The challenges facing these survivors are part of a larger system of discrimination and really a manifestation of a culture of male supremacy in our health-care system and our nation as a whole.” (Six months later, Schneiderman resigned as AG after four women accused him of assault.)

The settlement with the Brooklyn Hospital Center was a positive step toward systemic change. “It sent a ripple effect through the rape-crisis community in New York City because it was this act of hope and holding people accountable,” Wyse says. It was also just the beginning.

One month before news of the settlement with the Brooklyn Hospital Center broke, on Friday, October 13, 2017, Alison Turkos, who works at an abortion-rights nonprofit, was out late with friends at a bar in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. She ordered a Lyft to take her to Williamsburg—20 minutes away by car—where she was house-sitting for a friend. The driver proceeded to kidnap her at gunpoint, driving her around for 80 minutes, far out of her way to Liberty State Park in New Jersey, where at least two men raped her. On the following Monday, feeling like she was “held together by tape and glue,” Turkos went to New York-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital in Park Slope for a rape kit. “We never had a discussion about paying for things, but I was just like, what I just experienced—I mean, your body is a crime scene—I should never have to pay for that,” says Turkos, now 31. “It shouldn’t be on the backs of victims to have to pay for the harm that has been done to them.”

On November 3, she got a bill in the mail for $1,382.43. “I’m shocked—like, This has got to be a mistake. It’s got to be something in their system,” she says. “So I keep it, but I ignore it.” A second statement came on November 24. Now Turkos was thinking, This is going to go to collections. This is going to fuck up my credit. “Everyone said I shouldn’t pay it, but at that point in time, I didn’t have the energy to fight this fight. I just didn’t want to do it. So I paid it over the phone with my credit card and was like, This is done. Fine.” (She later found out her insurance had also been billed without her consent; it paid $4,706.31 toward the cost of her care.)

Four days later, a friend texted her news of the AG’s press conference. “I felt furious at first with myself because I was like, How were you so stupid? How are you supposed to be this smart, badass feminist and yet you paid for your own rape kit? How did you not know this?” Turkos says. She Googled around and found the New York AG’s Health Care Healthline (800-428-9071). She left a voicemail and got a call back three days later. The AG’s office told Turkos to call the hospital and ask to be refunded. The woman who answered the phone said she’d have to speak with her supervisor, and Turkos replied, “I’m more than happy to talk to your supervisor. I’m also more than happy to have the attorney general’s office call on my behalf.” She received a refund a day or two later.

But the refund triggered something in the hospital’s system to indicate that the bill had never been paid. So, on December 4, Turkos got a third bill in the mail. “I was like, What the fuck is happening? Is the attorney general lying to me?” she says. She called the hospital, and a woman told her, “Oh, it’s probably just a glitch in the system.” But on Christmas Day, she opened a fourth notice. “Every time I got a bill, it was like the hospital was saying, ‘Don’t forget that you got kidnapped and raped. Don’t forget that that is worth $6,000 to us,’” Turkos says. “I hated checking the mail. I hated getting envelopes with that little window in them. So I just wouldn’t check it for days or weeks.”

The AG’s office sent a cease and desist letter to the hospital. After receiving it, someone from the hospital’s financial department called Turkos to apologize and later followed up by mail to reiterate the apology and let her know she would receive no further bills. “This is supposed to be an institution that welcomes you with open arms, and instead it was, ‘Actually, no, we’re going to literally make you pay for it—emotionally, monetarily, mentally, physically,’” Turkos says. “I believe New York-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital is a perpetrator of harm against me. I don’t think they would see it that way, but it’s like, do you have any idea the emotional energy that took away from my healing?”

Turkos was proof of the AG office’s theory—that there were other survivors out there who had been billed. The agency widened its investigation, requesting records from 10 hospitals. About a year later, on November 29, 2018, then-AG Barbara Underwood, who was appointed to fill Schneiderman’s seat, announced that the state had found that an additional six hospitals had billed more than 200 sexual-assault victims for their rape kits. The charges ranged from $46 to $2,892. The investigation is still ongoing; today, the total number of hospitals New York has reached civil settlements with is 11. “I was surprised at the amount of hospitals that were implicated,” Safe Horizon’s Wyse says. “It was a huge moment. It sets a very clear precedent for how other states can handle this on a hospital-by-hospital basis. Because if it’s happening here, it must be happening in other places too.”

As part of the agreement, the hospitals refunded patients and agreed to implement policies to ensure they would not illegally bill survivors again. When it came to the level of wrongdoing, the AG’s office notes there are different degrees: Some of the hospitals had no procedure, some had procedures consistent with the law but were not implemented properly, some had procedures that were only partly accurate or only partly implemented.

The AG’s office points to high staff turnover and a lack of training as roots of the problem. In an ideal world, every rape kit would be conducted by a specially trained provider, known as a sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE). “If a hospital has a SANE program, they’re going to understand who the state-designated payer is and do the billing properly,” says Janine Zweig, associate vice president for justice policy at the Urban Institute, who coauthored a study examining state payment practices for rape kits. But nationwide, we have a shortage of trained examiners. According to the International Association of Forensic Nurses, only 17 percent of hospitals in the U.S. have access to a SANE provider. “In the places where completely untrained providers are faced with conducting these exams, I don’t really have a good sense that the hospital would understand how to bill it properly,” Zweig says.

In North Carolina, where 35 percent of hospitals have registered SANE providers, the North Carolina Coalition Against Sexual Assault (NCCASA), a victims advocacy organization in Raleigh, says it has received a handful of reports in the last six months from rape victims who were illegally billed, including those run by the University of North Carolina and Duke University. “I’ve been talking to hospitals about it, and they’ve been telling us that they’re doing what the statute says for them to be doing, that they’re not aware of the hospital billing patients, but the survivors we’ve spoken to have had our bigger hospital systems—UNC, Duke—bill them directly,” says Skye David, a staff attorney at NCCASA. David has tried talking to the state’s Department of Public Safety about the bills but says, “They’re not responsive. I think that until an investigation like what happened in New York happens here, there are going to be no real repercussions.”

Kristina Rose, former executive director of End Violence Against Women International, who previously worked in the Department of Justice’s Office on Violence Against Women, agrees that “it’s a training issue, it’s an education issue.” She points to telemedicine programs in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania that have off-site SANE providers instructing nurses on the ground by video on how to perform a rape kit in realtime as one way hospitals are trying to stem problems associated with the shortage. “I like to think we are making really good progress on sexual violence, but every day I’m reminded that we have so far to go,” Rose says. Reports of survivors being billed illegally are “one of those reminders. It’s bigger than having a protocol; we need to change the culture and the way people think about sexual assault. Until we have an ‘aha’ moment, we’re going to continue to see victims being charged.”

There wasn’t a trained examiner in the room when Smithson was given her rape kit. “I didn’t have a SANE nurse, which I’ve come to understand is something that some people have access to, and that’s really great, but it’s not universal. The moral of the story is, the system is broken,” Smithson says. “Everybody wants you to think there’s this civic infrastructure in place that will protect you when bad things happen. My take on that is, it’s a facade. It doesn’t exist.”

She often thinks about all of the other women who were billed “who probably felt just as awful as I did, but they just didn’t have the time or energy” to contest those bills. When I tell her about Turkos and how she only sought reimbursement for the rape-kit bill she had paid days earlier because of the settlement with Brooklyn Hospital, Smithson says, “It’s great to know that real people are benefitting.” Looking back on it all now, she says, “I’m glad I went to that hospital. The best thing to come out of this nightmare is that I went there and was billed so many times because, ultimately, it meant the situation was made right and other people have been helped.” She adds, “I’m the lucky one.”

Kayla Webley Adler is the Deputy Editor of ELLE magazine. She edits cover stories, profiles, and narrative features on politics, culture, crime, and social trends. Previously, she worked as the Features Director at Marie Claire magazine and as a Staff Writer at TIME magazine.