“Electability” Isn’t About the Candidate, It’s About Us

How much do you trust your fellow voters? That’s the real question.

In Tuesday night’s Democratic primary debate, the smallest yet and the last before the all-important Iowa caucuses, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren reminded her rivals—and the rest of the world—of a simple fact: Men aren’t electable.

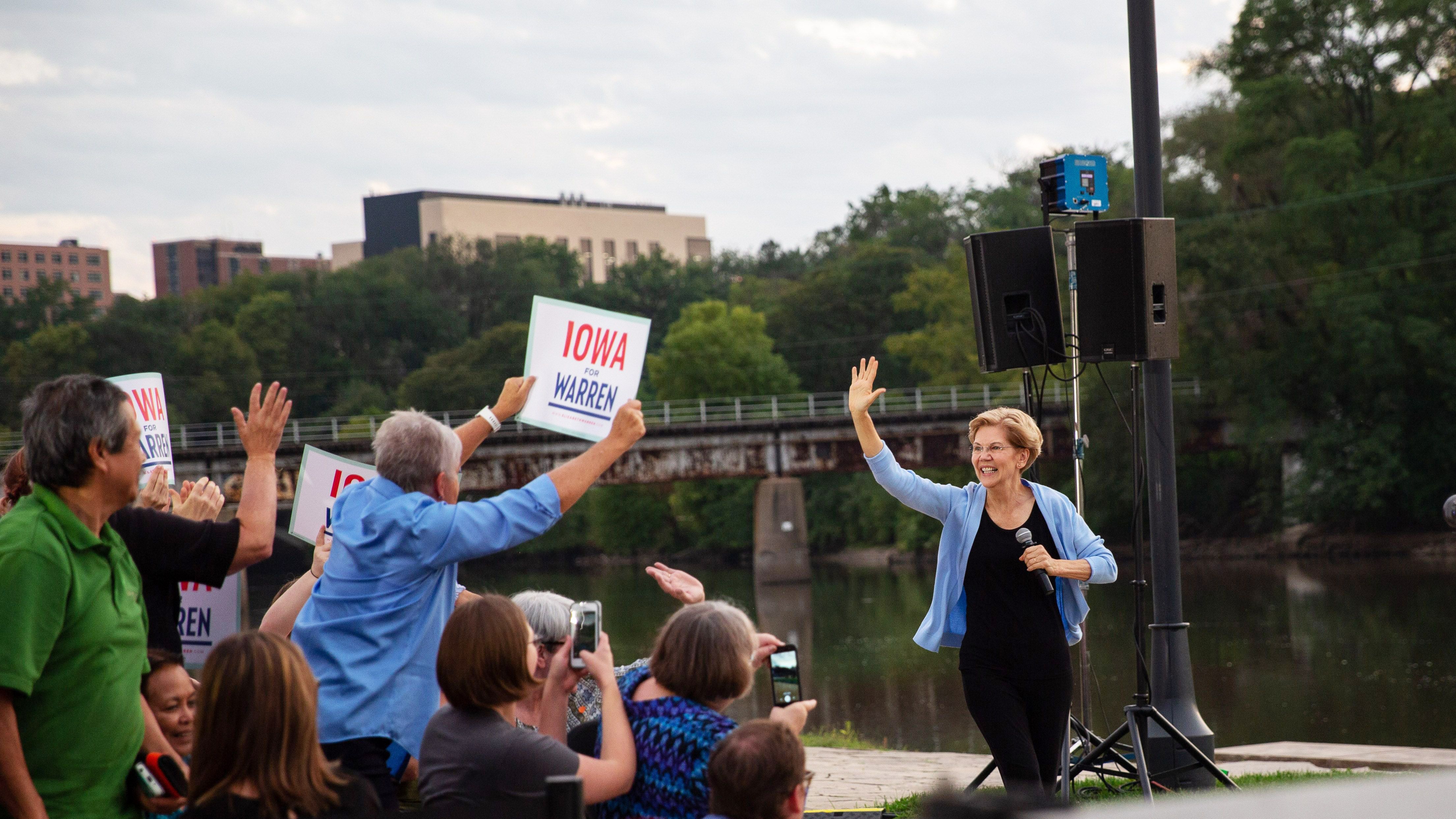

Men lose elections all the time. Constantly. And Warren came to Drake University in Des Moines armed with the receipts: The men on stage last night have lost 10 elections between them. Warren, and the only other woman on stage, Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar, have lost zero.

(Billionaire Tom Steyer has also lost zero elections, but that’s because he’s...never run for anything before.)

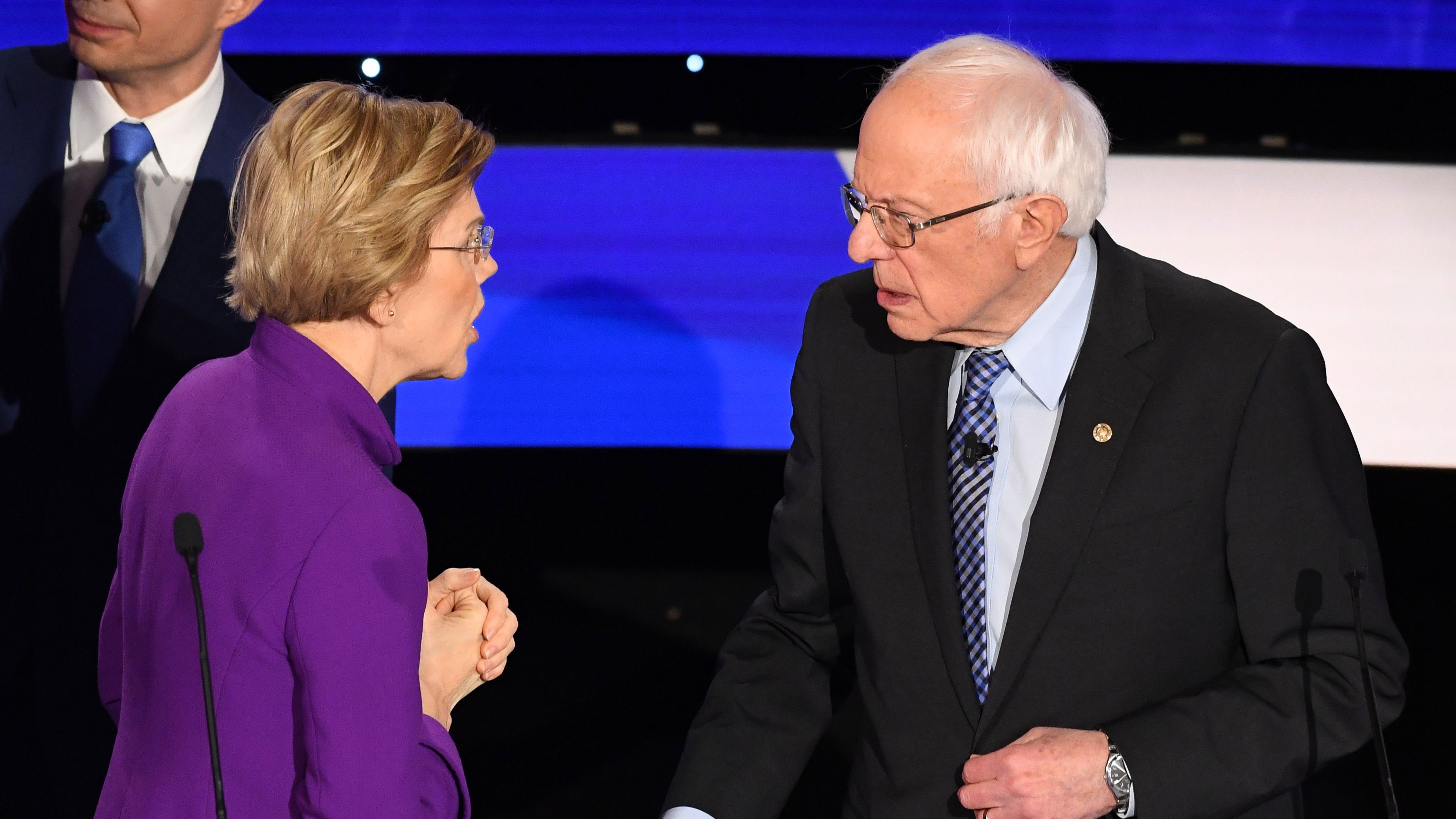

This particular iteration of the electability argument arose because earlier this week, CNN reported—and Warren confirmed—that in a 2018 conversation about Warren’s candidacy, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders told her that he didn’t think a woman could win the Presidency.

Here’s how Sanders remembers that conversation: “What I did say that night was that Donald Trump is a sexist, a racist, and a liar who would weaponize whatever he could. Do I believe a woman can win in 2020? Of course! After all, Hillary Clinton beat Donald Trump by 3 million votes in 2016.” On Tuesday night, Sanders again denied telling Warren outright that he didn’t think a woman couldn’t win.

Do you believe that sexism, racism, and other fears about the redistribution of political and social power will outweigh a candidate’s capacity to govern, to craft policy, to lead?

But of course, you needn’t say outright that you don’t think a woman can beat Donald Trump in order for your implication to be perfectly clear. It would be nice if a qualified woman could win, I’m all for it, but due to the easily manipulated biases of other people—not me, certainly not me!—she can’t, so why try?

And Sanders would have plenty of company in his fear that Trump would use the same sexist playbook that he used against Clinton, a playbook that Trump has emboldened the GOP to use against any number of women who get in the way of the Republican agenda—Nancy Pelosi, Christine Blasey Ford, and Ilhan Omar to name a few. In fact, it’s all but guaranteed that he’ll do exactly that.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The electability debate comes down to this: Do you or do you not think that playbook will work? Do you have enough faith in your fellow voters to pick the most qualified candidate? Do you believe that sexism, racism, and other fears about the redistribution of political and social power will—in the minds of other voters—outweigh a candidate’s capacity to govern, to craft policy, to lead?

Fears about electability, ultimately, come down to our understanding of other people. Our neighbors, our co-workers, our aunts and uncles. Our best understanding of people who live in far away states we might never have visited. This is what the electability argument always boils down to: I’ll vote for her, but I’m afraid they won’t.

Barack Obama was once considered ’unelectable,’ too.

It also feels like a pragmatic approach in a business where pragmatism is considered—depending on who you ask—either a high virtue or a necessary evil. And at a moment when, to many people, idealism looks like an unaffordable luxury. But there’s a pragmatic case to be made for “unelectable” candidates, too: in our very recent history, several of those “unelectable” candidates have, uh, gotten elected.

That’s because “unelectable” candidates have a way of bringing people to the ballot box who haven’t shown up for all the “electable” ones. Barack Obama did it. Bernie Sanders did it. And yes, Donald Trump, the ultimate “unelectable” candidate, did it. All three expanded the electorate, one of the hardest things to pull off in politics, by giving those new voters something they’d never had before: someone they actually wanted to vote for.

Warren was right to note that in addition to winning elections, the men on that stage have lost them, too. Just as electable candidates lose, “unelectable” candidates can win. Warren’s receipts were a reminder that electability is both an indisputable fact, and an utter mirage. Because it isn’t really about the candidate, it’s about us.

For more stories like this, including celebrity news, beauty and fashion advice, savvy political commentary, and fascinating features, sign up for the Marie Claire newsletter.

RELATED STORIES

Chloe Angyal is a journalist who lives in Iowa; she is the former Deputy Opinion Editor at HuffPost and a former Senior Editor at Feministing. She has written about politics and popular culture for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, The Guardian, New York magazine, Reuters, and The New Republic. Angyal has a Ph.D. in Arts and Media from the University of New South Wales.