Kathryn Garcia Has Spent Her Career Cleaning Up Powerful Men's Messes

The former department of sanitation commissioner has jockeyed her way to the front of a very crowded, very loud, very sexist NYC mayoral field. Will she make history?

It’s 9:45 A.M. on a Saturday, 18 days before the New York City mayoral election primary, and Democratic candidate Kathryn Garcia is riding in a green and blue sprinter van, her face—at least two feet tall—plastered on the outside.

The vehicle is decidedly un-Garcia. She’s not flashy. She says that prior to a few weeks ago, people rarely recognized her on the street. (Hard to believe, considering the van.) Her Twitter account was created only once she decided to run. Her campaign isn’t relying on any pseudo-celebrity appeal, like that of entrepreneur-turned-political-hotshot Andrew Yang or former MSNBC legal analyst Maya Wiley. It’s not a pageant, and it’s not, for better or for worse, too rah-rah. Instead, it’s built on the rather unglamorous—she spent six years heading up New York City's department of sanitation, for Chrissake. She bills herself as an everywoman, fighting to build a New York that, in her words, works for everybody. Today, she’s canvassing.

Garcia is in the van’s first row, leaning forward, head between the driver’s seat and passenger seat, directing our chauffeur, John. The team is headed to the first spot on the day’s tour, the grand opening of her new campaign office on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn; it’s only a few blocks away from the Barclays Center, where she started the morning with a photoshoot for this story, but Garcia is in wedges. “Turn up here,” she says, ignoring the directions provided by Google Maps. “It’s faster.”

She knows these streets. Garcia, 51, was raised less than 15 minutes from where we are now, the daughter of a teacher and a labor negotiator, in a multiracial family. (Garcia and two of her four siblings were adopted.) She now lives just two blocks from her mother’s home, a reason that, if she wins the election, she won’t move to Manhattan’s Gracie Mansion. It’s a point of pride, her status as a lifelong New Yorker—unlike, infamously, her biggest competitors in the race, Yang, who hails from the Hudson Valley, and Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, who came under fire during a debate for allegedly riding out some of the pandemic in his second home in New Jersey (which, no matter how close, is most definitely not New York).

Garcia riding to a campaign stop in her custom van.

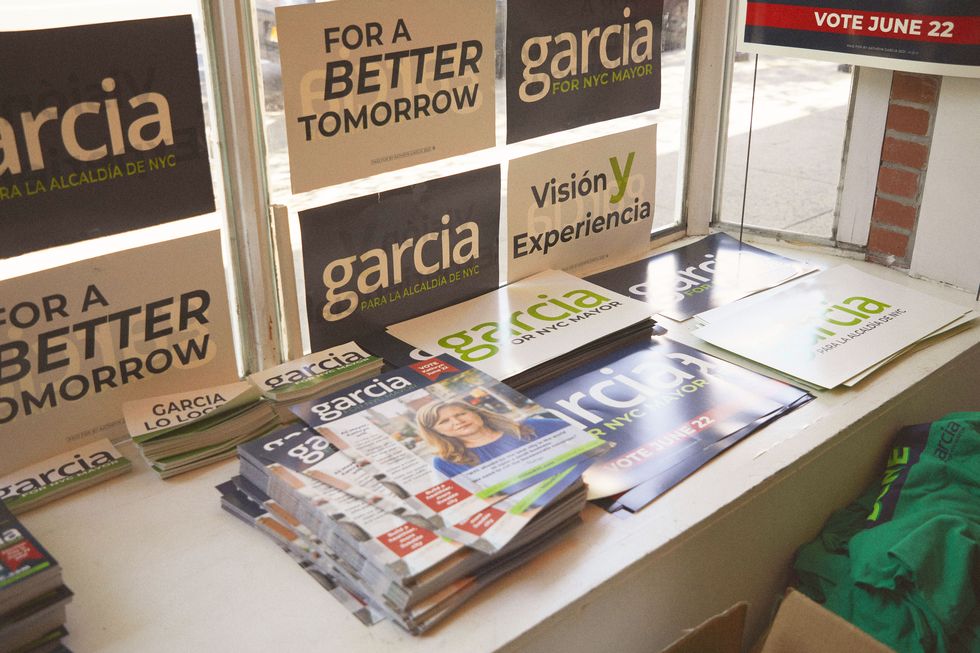

Garcia turns down the offer of a podium to address the roughly 60 people who have come to the grand opening to shake her hand or cheer her on (many of whom are campaign volunteers); she is, however, very excited about the step and repeat—posters of her papering a blank wall. John expertly parallel parks and Garcia enters the already crowded event. A fleet of staffers in green and blue shirts wave clipboards in a frenzy, fervently encouraging people to sign up for extra shifts on the phone bank. Garcia moves throughout the crowd, shaking hands, thanking volunteers. The buzz is palpable.

The commotion (and the van, and the Brooklyn headquarters) is new, thanks to Garcia’s sudden surge in the polls. Just weeks ago, Garcia was trailing a crowded pack led by mostly boisterous men. An endorsement from the New York Times editorial board in early May catapulted her campaign; she’s now considered a frontrunner. As of this week, she finds herself in the number two spot, just behind Adams. If Garcia wins the primary on June 22, she’ll be the democratic nominee in November. And in New York City, it’s a pretty sure bet that whoever has a “(D)” next to their name in the general election, has got it in the bag. If she does that, she’ll be the 110th mayor of New York City. And the first woman.

A New York public servant of 14 years, Garcia is no stranger to the ins and outs of running America’s biggest city (population: 8.3 million). Yet, despite her laundry list of qualifications, early on it was difficult to gain momentum and reach voters. She says Zoom campaigning was one of the reasons she wasn’t able to build name recognition. It’s easy to credit the Times’ support for her rise in the polls, but that would be diminishing her very long, very qualified resume, which includes roles in two mayoral administrations, and positions as the interim chair and CEO of the New York City Housing Authority and the commissioner of the Department of Sanitation. Garcia insists her late surge was by design; she didn’t want to peak too early. “This is a campaign that was designed for ‘May is the moment,’” she says.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Garcia, a longtime NYC public servant, has risen to number two in the polls.

Before voters knew her, many in government liked her—although they thought she’d never win. Armed with that underestimation, her competitors patronized her. In April, Yang said in an interview, “I think she’d make a phenomenal partner in my administration”; there are reports Adams has spoken similarly. Now that they see her as a threat, the praise has gone sour, inspiring literal trash talk about her work as Sanitation Commissioner.

“This is where my 14 years of experience are really shining, but it also says something about the fact that men do really believe that they should have the top job and that women should help make it happen,” she says of the change in tone. She thinks it’s entitlement that fuels much of the sexist rhetoric in the race. “I'll tell you right now, they steal all my lines,” she says. “In the debate, I said, ‘I am happy to have a conversation about my track record because I actually have one.’ And then Eric Adams got quoted as using my line.”

When Garcia decided to run, she understood the challenge ahead of her—she’s nothing if not practical. Not only would she have to win over notoriously tough New Yorkers, but she’d have to do it while navigating the sexist landscape that plagues female political candidates. “I know that it is harder for a woman,” she says. “You're going to have to work harder on the campaign. It's going to be tougher to raise money than it is for men. It's going to be tougher to get the endorsements that are part of the elected status quo—the people who've been trading favors forever. And that would just mean that we're going to have to work harder.”

After the office opening, Garcia climbs back in the van, headed for the Upper East Side, where she’ll canvas along an open street fair. As John drives up the FDR, Garcia points out a trash barge crossing the East River. During her stint as the Sanitation Commissioner, she banned styrofoam and implemented the nation’s largest composting program. She also sharpened her leadership skills: Garcia oversaw an agency of over 10,000 people. “It's about holding people accountable for the mission, but also just empowering them to do the work,” she says.

Under Bill de Blasio she was known as a pinch-hitter in times of crisis, someone to turn to to get it done—something of an unofficial campaign slogan. (She left the administration in September citing budget cuts and is now trying to distance herself from the unpopular mayor.) After Hurricane Sandy struck in 2012—causing the deaths of 44 city residents, an estimated $19 billion in damages and lost economic activity, and the displacement of thousands of New Yorkers—she brought 42 pumping stations and a water waste treatment plant online in just three days. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, she was dubbed the “food czar,” responsible for delivering 130 million meals to hungry or struggling New Yorkers.

Garcia is a textbook example of the “glass cliff” phenomenon—a theory established by two British researchers that powerful people tap women for leadership roles in times of crisis, when the chances of failure are greatest. She’s one of the millions of American women toiling away behind the scenes while suit-wearing men soak up the glory of their labors. “Of course I've had the experience of, like, I see something in the room and then a man says it and takes credit for it,” says Garcia.

And though a strength, her ability to “get it done” is often weaponized, too. One of the biggest critiques of her candidacy is that she’s not a visionary, but a doer. She doesn't see why she can’t be both. Garcia says she does, in fact, have a big-picture design for the city. “I want [New Yorkers] to have what my parents had,” she says. “I want them to have a livable, safe city.” She challenges the notion that her competitors actually have original ideas. “They keep copying my ideas,” she says. “Yang said we need to do a one city permit [for small businesses]. I know how to get this done. Yang actually came and said, this is a great idea. And I was like, how was he the visionary? Because he agreed with what I thought we should do.”

Still, it’s the “doer” mentality that fuels much of her platform. She claims she will only promise things she can actually accomplish. She wants to build 250 miles of protected bike lanes, invest in the subway’s fast forward program so that people can hopefully (actually) get to work on time, and house 50 percent of unhomed people before the end of her first term. “I want an ambitious but achievable program,” she says. That's a common approach in many of her platforms—aggressive, but not grandiose. Also on the docket: Introduce zero interest loans for small businesses, make all city school buses electric, and provide free childcare under the age of 3 for families who make less than $70,000 a year. Another priority: women’s health care. “I don't think anyone gives women's health issues the attention,” she says when asked if former mayors have done enough to protect reproductive rights. It’s why she’s planning to expand access to insurance and midwifery programs if elected. (Planned Parenthood of Greater New York Votes PAC endorsed Garcia as their number one choice.)

Before a few weeks ago, Garcia says she was rarely recognized—despite the van bearing her visage.

Over her years of working in the department of sanitation, she’s seen the sheer volume of waste New Yorkers produce every day. So she’s built her campaign, in part, on environmental conservation, and aims to expand the city’s composting project. On day one, she says, she’ll begin New York City’s transformation to a fully renewable energy economy. (Incongruously, she is carrying around a plastic water bottle to beat the 92-degree heat while canvassing, rather than a reusable one.)

The street fair is peak New York: Sausage stands and vendor displays line the sidewalk. It’s catnip for canvassing; campaign staffers for other, non-mayoral races are also handing out flyers, proselytizing. No one draws a crowd quite like Garcia. It seems recognition is no longer an issue: Voters flock to her and queue up for their chance to shake her hand or ask a question. In a moment so saccharine that it could have been planted, a little girl runs up to her and says she would be so excited to have a woman mayor.

It takes more than an hour to get down two blocks.

While she has no interest in being Yang or Adam’s number two, she thinks she could be a lot of voters’ number two at the polls; in fact, she’s banking on it. If enough people fill in her bubble for second choice (for the first time New York City is holding a ranked-choice primary), she could win. She’s massively electable, and that’s because, for the most part, her campaign has been breathtakingly uncontroversial.

But that doesn’t mean she’s evaded all scrutiny. In February, Philip Seelig, an attorney for the Sanitation Department enforcement agents, filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and says he plans to file a class-action lawsuit. The complaint alleges that sanitation agents, who are mostly women and nonwhite, received less pay and lower pension benefits than men doing similar jobs in another division known as sanitation police. For Garcia, who has built much of her platform on the ideas of equal pay and gender equity, the accusation marks her first real campaign disaster. Her team contends the situation is being misrepresented, that there are large differences between sanitation agents and sanitation police, the latter of whom carry firearms and must have a commercial drivers license to be able to plow streets during a snow emergency. They also note that, under Garcia's tenure, the number of sanitation chiefs of color doubled.

According to a Garcia spokesperson: "As a woman leading an agency that was 98 percent male, Kathryn was committed to building a sanitation department that was more equitable and diverse than what she inherited, and she got results. ...Kathryn knows political attacks don’t solve problems, hard work and responsible leadership does. And that’s exactly the kind of Mayor she will be; she will continue to create a more equitable and diverse city government."

The other two women still in the running, Dianne Morales and Maya Wiley (who was recently endorsed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and is also gaining steam) are more left-leaning, although Garcia calls herself as a “practical progressive,” which, she says, actually makes her more progressive than many other candidates. “The most progressive thing you can do is actually deliver,” she says. “If you have vision without execution, you haven't solved any problems. Vision does not get schools open. Vision does not get police reform done.”

Garcia chats with a supporter.

The only candidate who has fully embraced the idea of defunding the police is Morales—a top progressive contender until recent turmoil within her own campaign staff caused backlash. Outside of increasing the minimum age for new recruits from 21 to 25, and holding her police commissioner accountable—as Garcia says is of paramount importance—how will she help end police brutality that disproportionately impacts people of color? “This is not a city where we are going to get rid of our police force,” Garcia says. “You cannot hashtag a policy. It is always more nuanced. Do we need to make changes? Yes, we do, but we have to have a police force that is a service to New Yorkers, that are really our guardians and not warriors against communities, and communities feel protected regardless of the color of their skin. That is possible.”

While Garcia doesn’t agree with some of Morales and Wiley’s policy ideas, she does respect both. “I want to make sure that I'm supporting the other women candidates,” she says. If there is a woman running who aligns with your views, Garcia adds, pick the woman—it’s time for a new perspective. While she supports both candidates, she won’t name who she’ll bubble in second on her own ballot.

Garcia is one of three women left in the race for NYC Mayor.

The next stop on the trail is a multicultural fair in Harlem. Later, Garcia is headed to Queens, followed by an afternoon of meetings. She’s not the least bit tired, even though a race to become the first female mayor of New York must truly suck all of her available energy. “Women's voices are not held as compelling in the same way that men's voices are, and that needs to change,” she says. “Why am I running? Fifty percent of the population has not been represented in that chair.”

It’s both her ability to get it done and fresh, female perspective that she says poises her for the job. That, and the fact that she is fully a New Yorker. Her favorite restaurant in the city is Outerspace, a Cambodian and Vietnamese place in Bushwick, Brooklyn owned by her sister. She admits saying so “keeps me out of trouble with everybody else I'm friends with in the restaurant industry.” (For someone who doesn't define themselves as a politician, it’s a very diplomatic answer.) Her block is not the cleanest in Brooklyn—despite Garcia’s best efforts; you can catch her picking up trash on her street, often, she says, with her bare hands—but she loves it all the same. It’s her pet peeve when people balance a coffee cup atop an already full garbage bin. And unlike Yang, who was lampooned for claiming his favorite subway station is Times Square, hers is Astor Place, thanks to the wall art.

New Yorkers are sick of empty promises. They are sick of scandal. Coming out of a devastating year that almost gutted the city, New Yorkers want—need—a leader they can trust. “To put it in a very Brooklyn way,” she says, “[It’s time to] step up or shut up.” Whether that leader is finally going to be a woman is up to the voters, but Garcia wants them to know she’s up for the post-pandemic task. She understands the city is in a state of disrepair (a “shitshow,” as she put it last year), but she’s ready for the cleanup. That’s always been her job: taking care of the crap no one wants to see, cleaning up shit, and taking out the trash.

Megan DiTrolio is the editor of features and special projects at Marie Claire, where she oversees all career coverage and writes and edits stories on women’s issues, politics, cultural trends, and more. In addition to editing feature stories, she programs Marie Claire’s annual Power Trip conference and Marie Claire’s Getting Down To Business Instagram Live franchise.