How Social Media Helped This Attacker Find His Victim #HUNTED

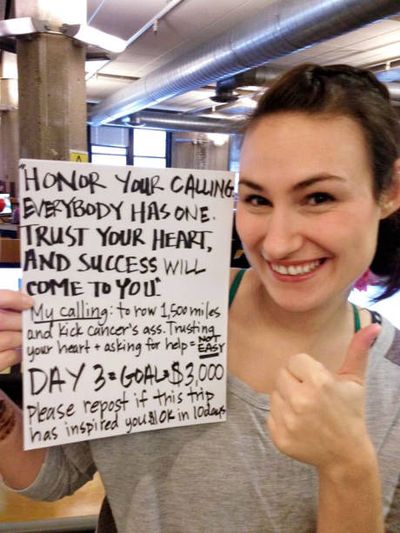

When Jenn Gibbons embarked on an epic 1,500-mile journey around Lake Michigan—all of it documented on social media—she never imagined the danger that would follow her.

It was four years ago, over Christmas at my parents' home in Battle Creek, Michigan, when I broke the news to my family: I was quitting my job as a customer-service rep at Groupon so I could row the perimeter of Lake Michigan. I knew it sounded crazy as I said the words out loud. "I'm going to buy a $30,000 used boat. It's 1,500 miles and should take me about two months. Nobody's ever done this before."

The goal was to raise money for Recovery on Water (ROW), a nonprofit I'd started in 2007 to support breast cancer survivors. While I'd never had a personal or family connection to breast cancer, I'd become passionate about the healing powers of fitness, especially among breast cancer survivors, who, I'd learned, could reduce their cancer recurrence by as much as 50 percent with regular exercise. What was once a passion had become my mission. Needless to say, my parents thought I'd lost my mind, but they've always known me to be stubborn and determined, and there was no doubting my commitment. My mind was made up.

That January, I kicked off a grueling training schedule that had me up every day at 5 a.m. to row for a few hours. While I'd rowed crew in college, it couldn't rival the intensity of my training. Evenings were spent alternating between CrossFit and Bikram yoga. During the day, I worked on ROW, reaching out to potential donors—my goal was to raise $150,000—while also trying to generate publicity for my endeavor. I even managed to coach rowing on the side. My life became planning, fundraising, training, and working. Nothing else. But there was nowhere else I wanted to be than on the water.

Nearly a year later, I bought a used 19-foot fiberglass oceangoing rowboat already christened Liv, which means "protector" in Norwegian. It had a small mattress that ran the length of the boat's 7-foot-long sleeping cabin. There was no kitchen—just a portable stove. Aside from the bed, the cabin could be filled with navigational equipment and food, but not much else. For the next several months, I studied every inch of Liv. If anything broke on my trip, it would be up to me to fix it.

By June of 2012, I was finally ready. It was early morning in Chicago, and many of my friends and family came out to see me set off. Local news crews captured my departure from the marina as I made my way north that first day. Outfitted with a satellite phone, GPS, and laptop, I logged the details of my journey at least once a day on Facebook and on my blog. I posted everything from a funny video of me eating a Twizzler with no hands to pictures of me so exhausted and sunburned that I could barely lift the oars. I called my parents once a week, and like everyone else, they could track my whereabouts at any given point and post encouraging messages.

The first really bad storm struck five days in, while I was on the west side of Lake Michigan, rowing toward Racine, Wisconsin. As the 10-foot swells tossed me, I released the anchor to steady Liv. I had to remain alert, lest my little rowboat crash into a bigger vessel. It was a steamy 90 degrees inside the cabin—opening the windows wasn't an option; the boat might take on too much rainwater and capsize. For eight hours, the waves threw me around, and in the suffocating, watertight cabin, surrounded by my own vomit, I could hardly breathe. But I powered through until calm returned the next morning, and I gradually paddled to shore. Liv had protected me. I finally felt like I could trust her.

Being on my own on the water felt incredible. I was accountable only to myself, my body, my goal. I never really got lonely or bored because there were so many things to be attentive to—the wind, the weather, the next crisis. About one month into my trip, I noticed storm clouds on the horizon and decided to dock early at Seul Choix Point Lighthouse, on a remote stretch of shoreline along Michigan's Upper Peninsula. The area was desolate and beautiful. The water was so clear you could see the bottom. At night, before closing up, a woman from the lighthouse gift shop came out to see if I needed anything and shared that the lighthouse was haunted—the old lighthouse keeper still stalks the shores. But I wasn't scared. I knew I would be the only person out there that night.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Rains poured the next day, forcing me to stay. That night I had a hard time dozing off because Liv kept slamming against the dock. I finally fell asleep at about 11 p.m. amid the smell of suntan lotion and bug spray. I woke up a couple of times and saw lights shining into the boat but didn't pay any attention to them. I'd remembered seeing a yellow Jeep pass by earlier in the day and figured it was a curious local.

At about 2 a.m., I awoke to the sound of the boat rocking against the dock. At first I thought it was a gust of wind, but when I looked out the window, I saw a man climbing aboard. I ran to the handles to close the door, but he was already forcing it open. All I could do was back up to the farthest wall at the other end of the cabin. The lights were off, with the only illumination coming from the strobe of the nearby lighthouse making its way around and around. It was a terrifying scene, me in the dark, catching glimpses of the man's face every time the light flashed in our direction. He wasn't big, maybe a little bigger than me. White. Probably in his 30s. Short hair. Grayish-green shirt, jean shorts, and tennis shoes.

"Take off your shorts," he demanded.

"No," I murmured.

"TAKE OFF YOUR SHORTS!" he shouted.

Maybe if he knew I was raising money for breast cancer survivors, he would leave me alone. "I don't think you know who I am! I don't think you realize who you are doing this to!" I yelled.

In a calm, matter-of-fact voice, he said, "Jenn, I know who you are and I knew where to find you."

He stripped off my black bike shorts and pinned down my arms. I squirmed like a trapped animal. I begged him to stop, but he kept going. But even before he could penetrate me, he ejaculated all over my body. It was disgusting. He was like a 15-year-old who came too fast. He just couldn't control himself—he was so excited. Traumatized, I vomited on him. And with that, he released my arms, and I started screaming hysterically. I hurled him off me, pulled up my shorts, and raced off the boat and up the dock to a nearby outhouse. He ran after me, and when he swung open the door to the outhouse, I shoved him into a mirror on the wall, which fell on top of him and shattered. Screaming all the while, I punched him maybe six times in the face until I got him outside; then I slammed the door shut, closed the latch, and pressed my body against the door. I was barefoot, clutching a shard of glass in that hot, stinking outhouse. I remember thinking, Get back to the boat! Get to the phone! But I was scared he was still out there. I waited for a while—it could have been 10 minutes or an hour, I don't even know—and then, slowly, quietly, I opened the door and bolted. I ran to my boat as fast as I could, climbed inside, and locked the door. I grabbed my phone to dial 911, then hesitated. It was nearly 3 a.m. On any other morning, I'd be up by 5 to begin rowing. If I called the police now, what would happen? Would my journey end here? I wrestled with the question for nearly 30 minutes before finally placing the call.

I felt like a zombie telling the female police officer what had happened. She drove me to the nearest hospital, in a small town called Manistique. I could sense this was probably the only rape kit the young doctor in this far-flung place had ever performed. He nervously explained that they'd have to swab my body—my vagina, my butt—so they could get DNA. It was humiliating and dehumanizing. I couldn't go to the bathroom until it was over, and no one could even comfort me because I was, in effect, a piece of evidence.

My parents drove seven hours through the night and arrived at the hospital the next morning. We all checked in to a local hotel, where we stayed for the next few days as the police conducted their investigation. That first night I must have taken seven showers—nothing could make me feel clean.

I told the police what the attacker had told me, that he knew my name and where to find me. How could he have known I was in such a remote spot unless he was following me? And how could he have been following me unless he was monitoring my movements online? My boat had a tracking device to pinpoint my exact location at any given moment. When the police told me that sexual assaults in the area were rare, I became convinced that my attacker had found me through social media.

Though I was frightened and devastated, in the days that followed I longed to return to the water. I had no intention of giving up. After consulting with the police, we agreed that I'd continue by bike, followed by state troopers. Once I'd reached a safe point where marine police could follow me on the water, I would resume rowing.

Naturally, my parents were upset. "You don't have to do this! You can come home, it's OK, you've done enough," my mom pleaded. My closest friends urged me to quit. They wanted nothing more than to keep me safe. But I was adamant—and angry that someone had tried to interfere with my mission. Though I was undoubtedly still in shock, I knew I needed to exorcise my demons by rowing. I thought about all the women I'd met over the years, how they rowed through chemo and radiation, how they found the strength to go on despite being physically and emotionally shattered. I finally understood their courage and will, and like them, I believed exercise would heal me.

Four days after my assault, in the driving rain and trailed by police, I set out on a bike. My ribs, knees, and arms were covered in bruises, from both the rowing and the attack. I wept for most of that first day. Though I continued logging the details of my journey, at the suggestion of the police I carefully avoided references to where I was.

I finally returned to my boat, but I never slept on it again. I'd lost all trust in Liv as my "protector." So after a day of rowing, I'd pull into harbor and make my way to a nearby motel. It went on like this until I reached the point from where I'd started, the Chicago harbor, 59 days and 1,500 miles later. I sobbed as I rowed into the marina. It was a beautiful day, and so many familiar faces greeted me. I climbed out of the boat and fell into their arms. It felt so good to be home.

Though my rape kit proved inconclusive, I'm still comforted by the fact that my story is out there and may lead to my attacker's arrest down the road. It wasn't easy returning to a normal life at home. I experienced anxiety about routine things, like walking to my car alone. At first, I didn't talk to a therapist—though my family and friends encouraged me to—because I thought I'd just deal with it and move on. But it didn't quite work out that way. I suffered flashbacks, and while I knew deep down the attack wasn't my fault, I still felt guilty about things I could have done differently that night, like locking the door to the boat or fighting him off more forcefully.

Eventually I sought treatment and was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Therapy has helped a lot. I've come to realize that sharing is the only way to heal. You aren't made stronger by keeping your trauma a secret or protecting someone who hurt you. I am now in a wonderful, healthy relationship with a supportive and patient man. But it took a lot of time and hard work to get to this place.

Every day, I am making the most of what good and bad have come to me in life. I've learned that when I think about my trip, it's tempting to get angry and ask why bad things like cancer or sexual assault happen to good people. But by focusing on the good instead, by being patient with myself when setbacks arise, I have found peace and a whole lot of happiness.

My wish is that when people think about my journey, they remember it the way I do: that I did something no one had ever done before—I rowed a small boat around a pretty big lake for an amazing group of women, and nobody, absolutely nobody, could stop me.