I took my first psychiatric medication when I was 19 years old. I'd been diagnosed with depression and an eating disorder, and was handed a whole slew of drugs to try. It was like whack-a-mole with my brain chemistry.

To add insult to injury, I felt guilty about my depression, since, rationally, it seemed like I had nothing to be depressed about: I had a loving mother, I was going to an excellent college, I had friends. I was constantly terrified—of nothing in particular—which became the hallmark of my emotional state.

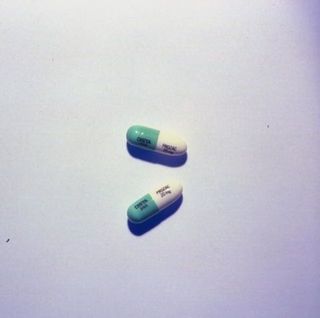

It took a long time to find the right meds. I went through the usual suspects: the trusty ol' Prozac, the ubiquitous Xanax. I could feel them, but they didn't make me better. "Be patient," I was told. "Focus on eating," I was told.

The medications I tried mostly made me feel like there was cotton wool between me and the world, a dulling of the senses that drove me even more nuts than I already was.

Eventually my constant fog and flux meant I had to take a leave of absence from school. I had nothing but time on my hands: I wasn't allowed to do much other than pay attention to getting better. I remember watching the trailer for Silver Linings Playbook and smiling while Jennifer Lawrence listed the medications she'd been on; I'd been on every single one of the drugs on her list. When she laughs and says, "Klonopin, yeah," I felt like we were friends.

We list-rattlers are bonded over something no one else gets: The endless "fixes" that don't fix anything just make you think you are, in the end, unfixable.

The medications I tried mostly made me feel like there was cotton wool between me and the world, a dulling of the senses that drove me even more nuts than I already was.

I did find one that allowed me to feel again: Effexor. I could feel sad. I could feel depressed. But I could also feel joyful, excited, and eager. I could feel up and down, high and low, instead of the constant pain—or the worse nothingness.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

But after about a year, I tried—with a psychiatrist's blessing—going off meds altogether. I proceeded to make some of the worst decisions of my life: I broke up with a woman I was head over heels in love with in order to get back together with a fleeting summer romance—who lived in another country. It wasn't smart. It wasn't something medicated me would have done. It was an irrational, fearful, spur-of-the-moment need for drama. Something to shake the stagnant little plastic flakes in the snow globe of my world loose.

I will never forgive myself for what I did next: I soon broke off that long-distance relationship too, and started lamenting the loss of my more serious girlfriend. The long-distance romance didn't speak to me anymore. Neither did the woman I was in love with.

I went back on the meds.

Luckily my reliable Effexor kicked right back in. I still had periods of depression, but I recognized them for what they were—an illness—and got through them. But after almost five years of never forgetting to take my morning dose of 150mg, I flew from my home in Israel to New York City for my last semester of college...and accidentally left my meds behind.

I broke up with a woman I was head over heels in love with in order to get back together with a fleeting summer romance.

I didn't think it would be a big deal. My mother said she'd ship them to me. They were going to arrive within a couple days.

But then I started having what is still one of the most unpleasant experiences of my life: brain zaps. Brain zaps feel like an electric current going from the nape of your neck to your eyeballs (a common side effect of Effexor withdrawal). It also feels like being drunk in the worst, least fun way possible. I couldn't concentrate on anything. All I wanted to do was sleep. My depression was kicking in fast.

I finally went to my school nurse, who, as it turned out, was able to give me an emergency script. Within another two days, I felt back to normal, but I was spooked. That one experience of withdrawal made it so that every time I took my meds late (which happened if, for example, I ended up sleeping elsewhere unexpectedly, without my bedside medication) I began experiencing deep withdrawal almost immediately. It was hell.

I started living in constant fear of forgetting to take it, and of what those repercussions would wreak on my life.

At the end of my senior year of college, I couldn't stand to be on the Effexor anymore. I found a new psychiatrist and submitted to the slow, torturous process of switching to a new medication. When this new psychiatrist heard my symptoms, she also diagnosed me with anxiety—shocked that I hadn't been told I had it before.

I am now on a variety of other things, both antidepressants and anti-anxiety meds; it's not the same. I feel better some days, worse others. Maybe it's the stressors of "real life"—i.e. supporting myself, living in an expensive city, working as a freelancer. Maybe the nature of my mental illness has changed. Brains are tricky like that. But this I know for sure: I fluctuate more than I used to.

I miss being able to take a single pill in the morning rather than the plethora arranged on my bureau at home—I miss my one-stop-shop. But I still hope (with fingers and toes crossed, eyes shut tight, wishing upon a star) that I'll find something that works well again, and that it won't be as onerous as my current medication routine.

How are mentally ill folks supposed to function when access to affordable mental health care is so limited?

And yet I'm one of the luckier ones. I know plenty of people who don't have the resources to get the treatment I do; plenty of people who are drowning under the financial burden of being mentally ill.

I could be one of them: I can't afford good health insurance, so I pay mostly out of pocket. I work myself sick to be able to do this, and I'm lucky enough to lean on my mother to help support my medical expenses when necessary.

And this strikes me as counter-intuitive. How are mentally ill folks supposed to function when access to affordable mental health care is so limited? Health care, and especially mental health care, should be accessible to everyone, not only to the privileged few.

Even still, here I am, on my solo journey towards hopeful eventual medicated bliss. I might be feeling better if not for the stress of trying to afford to make myself feel better. Or I might be another Odyssean quest away from the right brain-chemistry cocktail.

Follow Marie Claire on Facebook for the latest celeb news, beauty tips, fascinating reads, livestream video, and more.

Ilana Masad is a fiction writer, a critic, and the author of the novel All My Mother’s Lovers.

-

18 Spring Travel Essentials I'm Scooping Up for My European Vacation

18 Spring Travel Essentials I'm Scooping Up for My European VacationSunglasses, sneakers, and sundresses.

By Brooke Knappenberger Published

-

Amid Dire Reports About His Health, the Palace Issues a Wide-Ranging Update on King Charles

Amid Dire Reports About His Health, the Palace Issues a Wide-Ranging Update on King CharlesThe news was accompanied by a never-before-seen photo of the King and Queen Camilla, taken the day after their 19th wedding anniversary this month.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Anne Hathaway Says This ‘The Idea of You’ Sex Scene Is the “North Star” for “Cinematic Sex”

Anne Hathaway Says This ‘The Idea of You’ Sex Scene Is the “North Star” for “Cinematic Sex”The actress said it “makes it about her pleasure.”

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"Senator and breast cancer survivor Amy Klobuchar is encouraging women not to put off preventative care any longer.

By Senator Amy Klobuchar Published

-

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My Body

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My BodyI'm plus size, but after I decided to pose nude for photos, I suddenly felt more body positive.

By Kelly Burch Published

-

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?Much like abortion, surrogacy, and IVF, becoming an egg donor was a reproductive choice that felt unfit for society’s standards of womanhood.

By Lauryn Chamberlain Published

-

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in Check

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in CheckGut health = wealth.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo Olympics

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo OlympicsShe withdrew from the event due to a medical issue, according to USA Gymnastics.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Truth About Thigh Gaps

The Truth About Thigh GapsWe're going to need you to stop right there.

By Kenny Thapoung Published

-

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” Condition

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” ConditionDespite having no outward signs, they can be brutal on the body and the mind. Here’s how each woman deals with having illnesses others often don’t understand.

By Emily Shiffer Published

-

The High Price of Living With Chronic Pain

The High Price of Living With Chronic PainThree women open up about how their conditions impact their bodies—and their wallets.

By Alice Oglethorpe Published