Into Africa

Driven by equal parts passion and ambition, young Americans are taking a career path less traveled to Rwanda, turning life experience into a world of good, almost 20 years after the genocide.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Marie Claire Daily

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Sent weekly on Saturday

Marie Claire Self Checkout

Exclusive access to expert shopping and styling advice from Nikki Ogunnaike, Marie Claire's editor-in-chief.

Once a week

Maire Claire Face Forward

Insider tips and recommendations for skin, hair, makeup, nails and more from Hannah Baxter, Marie Claire's beauty director.

Once a week

Livingetc

Your shortcut to the now and the next in contemporary home decoration, from designing a fashion-forward kitchen to decoding color schemes, and the latest interiors trends.

Delivered Daily

Homes & Gardens

The ultimate interior design resource from the world's leading experts - discover inspiring decorating ideas, color scheming know-how, garden inspiration and shopping expertise.

THIRTY MINUTES FROM central Kigali, Rwanda, tucked behind a rutted, red dirt road, are the Ndera headquarters of Gardens for Health International (GHI)—an alfresco bungalow and office space on five acres of farmland that unfurl down into a valley. In the fading light, sunflowers tower over vines dripping with passion fruit, while pineapples ripen alongside cilantro, arugula, beets, and papaya. A dinner party illuminated with votive candles and paper lanterns is in full swing. There is a massive outdoor wood-fired stove, and the indoor kitchen is stacked with freshly picked ingredients for mango guacamole, pesto, and pumpkin-sage soup. Some guests do prep work, while others set the table for more than 50 people or relax with a cold Primus, a Congolese beer. The resulting feast is more satisfying because of its collaborative nature. The same could be said about GHI itself. Julie Carney, 27, Emma Clippinger, 28, and Emily Morrell, 26, founded the organization while still in college in the U.S. to provide nutrition education and reduce childhood malnutrition.

Earlier, a denim-shorts-and-Wellies-clad Carney tended the crops, strolling through rows of greens and plucking a leaf from a moringa tree, which has a sharp aroma, vaguely akin to horseradish. "They call it the 'miracle tree' because it's loaded with vitamins," she says. "We teach mothers to grind the dried leaves into a powder to add to porridge for their children." By "we," Carney means not only GHI's 28-year-old executive director, Jessie Cronan, but local colleagues as well. These young American expats are just a few who have brought their ideas for a more equitable world to this tiny country (about the size of Massachusetts) of 12 million, and are quick to say they're not there to fix or save the country but to channel their energy toward Rwanda's own vision of the future. "We view our work here as one of partnership and collaboration," says Carney. "We don't want or deserve all the credit."

Photo: Claire Ingabire, Julie Carney, Annonciathe Muhayimana Niyibizi, Emma Clippinger, and Naomi Musabyimana of Gardens for Health International, whose mission is to alleviate malnutrition in children.

The vibe in Kigali is electric with passionate people pursuing a shared goal to work in development and make a difference. (There was a time when that impulse might have been satisfied by volunteering with the Peace Corps—now, it's working at an NGO [nongovernmental organization] or even setting up your own shop.) People like Cher-Wen DeWitt, 24, the former country director of HIV outreach program FACE AIDS, which collaborated with Boston-based Partners in Health, who now works at an agriculture NGO that provides aid to farmers. Or 28-year-old Sarah Manion, who has worked in five African countries. Having served as the technical adviser at the Ministry of Infrastructure, Manion now consults for Karisimbi Business Partners International on building and growing local companies. "There's a vibrancy and a sense of forward motion that I've never felt in any other place," Manion says. Or Sasha Fisher, who moved to Kigali fresh out of college to start Spark MicroGrants, which funds development projects that rural communities decide upon, such as forming agricultural cooperatives or building main power lines or schools. "The Rwandan people know how to solve their problems so much better than I ever will," Fisher, 25, says. "People starting NGOs and finding new approaches to alleviating poverty care so much about the projects and so little about their egos."

IT'S BEEN NEARLY 20 YEARS since the Rwandan genocide, in which an estimated 800,000 mostly ethnic Tutsi were killed by the Hutu majority over 100 days. Since then, Rwanda has emerged from its grim past to become one of the safest and most livable places in Africa, its clean, green capital a magnet for social entrepreneurs seeking hands-on opportunities. Cell phones buzz ceaselessly over lattes at Bourbon Coffee, and in Kigali, people are as serious about their work as they are about unwinding after hours at Papyrus Bar's rooftop lounge or at happy hour around the pool of the Hotel des Mille Collines. It's hard to comprehend that this is where the horrific events dramatized in the 2004 film Hotel Rwanda took place. The movie starred Don Cheadle as manager Paul Rusesabagina, who, in April 1994, allowed more than 1,200 Tutsi and moderate Hutu to take refuge in his hotel as the United Nations and world leaders looked on. By mid-July, the streets were awash in blood, and Rwanda's infrastructure had been annihilated. The leader of the Tutsi rebel force, Paul Kagame, took charge of the country and the reconciliation, and he remains president today. (In 1998, President Bill Clinton and U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan apologized to survivors and the Rwandan Parliament, respectively, for standing idle during the atrocities.) Claire Ingabire was 15 during the genocide and a full-time mother by age 17. Today, she supervises 12 field educators at GHI. "There was so much that needed to be fixed after the genocide," says Ingabire, now 35. "When GHI came, it took the time to train Rwandans like me to guide other Rwandans. We are like family, together in everything we do."

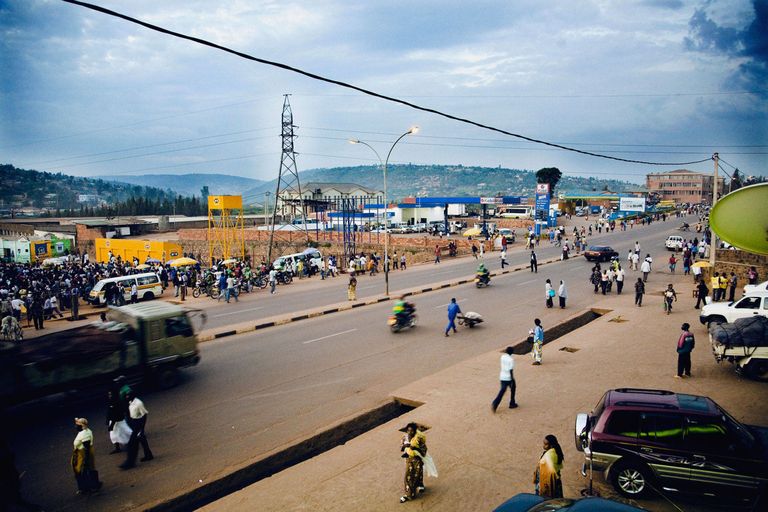

Photo: The downtown area of Kigali, Rwanda's capital city

Under Kagame's strict rule, political dissent that could promote a return to ethnic divisiveness is suppressed, plastic bags and litter are illegal, and any identification of the "H" or "T" ethnic groups is frowned upon. "We're all Rwandans now" is the mandated refrain. Police disperse even a small crowd, as any public gathering might be perceived as a threat. The country boasts modern highways and high rates of literacy. It has the world's highest percentage of women in government (64 percent). Its health-care plan, which insures nearly 98 percent of citizens, is considered the gold standard for the developing world, and the economy has improved more than 8 percent a year over the last decade. But there is still great poverty in rural areas, and 43 percent of children under age 5 are chronically malnourished. The government has been criticized for imposing restrictions on civil liberties and violating human rights, and next door in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the world's deadliest war has raged for almost two decades, a reminder of the fragile stability of the region.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

A mainstay of Kagame's plan has been to reconstruct the country into nothing short of Africa's greatest success story. To that end, Rwanda discerningly opened its doors to outside aid, investment, and ideas. "Having come from the history we inherited, we needed any help that we could get," says Clare Akamanzi, chief operating officer of the Rwanda Development Board, which is leading the country's drive for private investment in information technology, business, and tourism. "We didn't have the necessary expertise, knowledge, and resources. But we were determined to make it."

Photo: Daisy Freund on a moto taxi, a ubiquitous mode of transportation in Kigali. "I ran a restaurant in Rwanda," says Freund, who managed Heaven restaurant, opened by two other Americans. "If that doesn't give me confidence, I don't know what would."

Entrepreneurship has flourished under such a strategy. "It is fairly easy to work with the government. In my case, opening a restaurant, it took just two days to incorporate and certify all of the necessary paperwork," says Alissa Ruxin, 38. Seven years ago, she and her husband, Josh, relocated to Rwanda to start a family. Josh had seen great promise in the country since a consulting project first took him there in 1999. In 2003, he returned to launch Health Builders (then called Access Project), which has built five health clinics and provides management assistance to 89 other clinics and hospitals throughout the country. The couple also opened Heaven, a restaurant and inn, and their experience is chronicled in Josh's recent memoir, A Thousand Hills to Heaven.

THE BACKYARD OF THE Ruxin stucco home has a garden where the couple raises mint for Heaven's storied mojitos. (It also bears a scar from the past: Shortly after they moved in, a woman appeared at their door to exhume the bones of her brother buried behind the house during the genocide.) The Ruxins realized that the private sector could be as pivotal as nonprofits in moving the country forward. Borrowing from friends and family and maxing out on loans, they built Heaven with a clear goal in mind: "The best thing that you could possibly do for Rwanda—for health, for development, for political stability, for everything—is to create jobs in a sustainable way," Ruxin says. She sees plenty of Americans come and go, and is amused by the reality-show aspect of the ever-changing expat scene, especially the gender ratio. "It's about nine women to every one man who comes," she says. "It doesn't matter how awkward or socially inept a guy you are. We had a friend who had a different girlfriend every time we saw him." But transients might be adventure-seekers lacking a genuine dedication to rebuilding Rwanda. "People e-mail us every day asking about jobs. I tell them there is opportunity, but you've got to come on your own ticket and demonstrate your commitment to being here," says Ruxin. "They know within a few weeks whether or not they can hack it. It's not for everybody."

Photo: "I really feel like the government has created an atmosphere in which everyone wants to improve," says Sarah Manion, a consultant, shown here with members of a women's weaving cooperative.

Some, like Elizabeth Dearborn Hughes, are in it for the long term. As a college sophomore, she read about the genocide in The Economist. "I knew I had to go, and I'd figure it out once I got there," says Dearborn Hughes, now 29. Within a few months of arriving, she met her now-husband, Dave Hughes, a Hong Kong–raised Brit who had come to Rwanda for similar reasons. Together they started the Akilah Institute for Women, a three-year college specializing in hospitality, information technology, and entrepreneurship for young women from low-income rural communities. Ninety-seven percent of the student body are the first in their families to pursue higher education. Akilah's mission dovetails with the government's desire to grow both the tourism and technology industries, and the school works closely with several offices, including the Ministry of Education and the Workforce Development Authority, to design a curriculum based on gaps in the workforce. More than 90 percent of the first two graduating classes have secured jobs or internships. Florence Mukundwa, 29, lost 72 members of her family in the genocide and at age 9 was left to take care of three younger sisters. After completing her studies at Akilah in 2012, she started a business making clothes and accessories from local fabrics and has since hired four other women for her company. "I have told Elizabeth that what Akilah has done for me, I will do for others," says Mukundwa. "It came from being inspired by her. If she can do this, I have it in me to do it." It's these individual victories that propel the country forward. "If, after everything it has been through, Rwanda can emerge as a success story," says Dearborn Hughes, "it raises the bar for every other country on the continent."

A lofty goal, perhaps, and one that requires a commitment not just to the necessary toils—fundraising, navigating HR issues—but also to being far from home, living on meager budgets, and rarely taking a vacation. "I wouldn't want to be doing anything else," says Dearborn Hughes. "But it's 24/7." A social life requires some creativity (and lots of board games). But a movie theater opened last spring, there are Monday quiz nights at SoleLuna restaurant, doughnuts and bagels at J.Lynn's on Saturday mornings, and weekends at Lake Kivu beaches. While some have left for opportunities elsewhere (GHI cofounders Clippinger and Morrell returned to the U.S. to attend law school and finish a pediatric residency, respectively), others have made Rwanda their home. "We formed a great group of Rwandans and Americans who are trying to create change together," says Sasha Fisher. "My generation has this incredible opportunity to test out new ways to provide services to people. It is mind-blowing how much we are able to do."

Photo: With her husband, Elizabeth Dearborn Hughes started the three-year college Akilah Institute for Women in Kigali, where 97 percent of students are the first in their families to pursue higher education.