The Last Clinic Standing

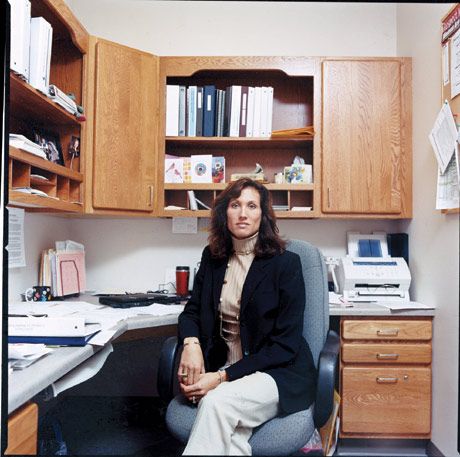

On most Monday mornings, Dr. Miriam McCreary wakes up before her pet parrot at 5 a.m. and dresses in the dark in order to make a 7:20 flight from her home in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to her office in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Marie Claire Daily

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Sent weekly on Saturday

Marie Claire Self Checkout

Exclusive access to expert shopping and styling advice from Nikki Ogunnaike, Marie Claire's editor-in-chief.

Once a week

Maire Claire Face Forward

Insider tips and recommendations for skin, hair, makeup, nails and more from Hannah Baxter, Marie Claire's beauty director.

Once a week

Livingetc

Your shortcut to the now and the next in contemporary home decoration, from designing a fashion-forward kitchen to decoding color schemes, and the latest interiors trends.

Delivered Daily

Homes & Gardens

The ultimate interior design resource from the world's leading experts - discover inspiring decorating ideas, color scheming know-how, garden inspiration and shopping expertise.

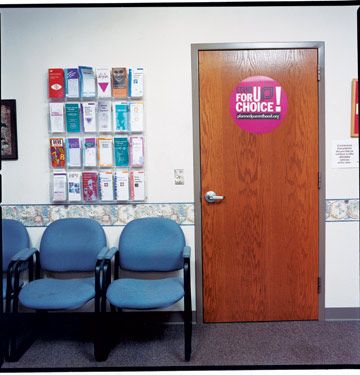

The Planned Parenthood where she works looks like a typical 21st-century American abortion clinic. The bulky brick exterior defends the edifice against bombs. Deliberately high windows protect those inside from snipers. A rear parking lot hides patients from protestors who might hurl slogans, spit, or Molotov cocktails. On Monday mornings, the patients-many of whom wear hats and all of whom study the ground-enter the locked, bulletproof doors pregnant. Since no South Dakota doctor will work at the clinic, 71-year-old gynecologist McCreary, grandmother of 10 and daughter of Lutheran missionaries, hops her early flight to Sioux Falls, population 141,000. Her husband, a retired businessman, kisses her good-bye, then tries to get through the day and get past his worries-foreign terrorists who hijack airplanes, domestic terrorists who murder doctors-with military-history magazines. The Minneapolis flight is often delayed; Midwest weather is iffy. So a Planned Parenthood staff member regularly watches the sun rise over a tall-grass field from the curb in front of the regional airport, where she waits for the doctor to arrive. Week after week, she comes to understand how frontier women periodically went crazy from the prairie wind's whisper-whistle, while back in the clinic's waiting room, a more complex tension thickens despite the generous supply of People magazines.

To begin a surgical abortion, Dr. McCreary injects a patient's cervix with an anesthetic. She'd like to offer general anesthesia, but there aren't enough nurses at the clinic to watch IV lines. So Dr. McCreary gives the women what she calls "verbal anesthesia." "I talk to them," she says. "Most have the same favorite topic: their kids." Sixty percent of abortion patients in the U.S. are already mothers. Next, Dr. McCreary dilates her patient's cervix to about the width of a pen. Then, taking something that looks like a mini vacuum-cleaner hose, she sucks out the contents of the uterus. Sixty days after conception, a fetus is about the size of a kidney bean. It has a head, a rump, and tiny webbed fingers, but limited brain function. Along with the placenta, Dr. McCreary pulls the fetus, in pieces, into a glass jar. Like amputated limbs, abortion material is considered regulated medical waste and is cremated or incinerated. About three hours after entering the clinic, most patients leave with their wombs empty- though about twice a month, a woman is so distraught that Dr. McCreary sends her home still pregnant to reconsider her options. "I tell her, 'Think about what you really want to do,'" says Dr. McCreary. "I say, 'We'll be here if you need us.'"

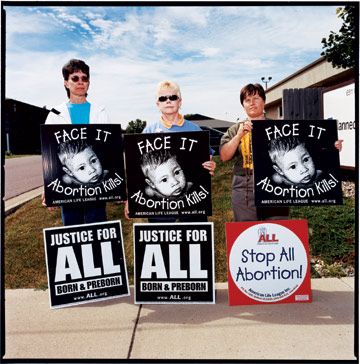

On the sidewalk in front of the brick fortress, two other grandmas, from Brookings County, SD, recite the rosary. Each carries a poster of a baby that reads, "Look it in the face." "This clinic protects rapists," one informs me. "If a woman has been raped by a family member, the law says you're supposed to report it. But if you come here and get an abortion, it doesn't get reported. The man gets a free ride." Then she confides, "And the clinic sells baby parts to manufacture cosmetics." It would be an abortion clinic like any other, except that the Sioux Falls is the last facility in all of South Dakota, a state of 775,000 people scattered across some 77,000 square miles. It is also the most imperiled clinic in the country-endangered not from the kaboom of violence, but from a silent smash of law.

Last winter, the state legislature passed House Bill 1215, The Women's Health and Human Life Protection Act, which bans virtually all abortions, even in cases of rape, incest, and threat to a woman's health. "If you have high blood pressure or heart disease and a pregnancy will make the condition much worse, too bad," says Sarah Stoesz, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood in Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota. "Even if you already have small children. Same if you're carrying a severely damaged fetus." For now though, the Act cannot be enforced. The South Dakota Campaign for Healthy Families gathered enough signatures to put it to a statewide vote on November 7. On that day, if South Dakotans choose to rescind the Act, pro-life advocates will likely introduce a slightly less-stringent ban in the State Legislature. If South Dakotans vote to uphold the Act, Planned Parenthood will file a federal lawsuit against the state. Either way, both sides agree, the battle will rise up through appeals courts, and sooner rather than later, the U.S. Supreme Court will decide-based on HB 1215 or similar measures introduced in Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Georgia, and Tennessee-whether abortion remains legal in America.

Politics normally don't interest Nancy, 26, a cherubic-looking hairstylist from Aberdeen, SD. But when she discovered she was pregnant in late May 2006, Nancy (not her real name) wound up thinking a lot about the political intricacies of the controversial procedure, especially how much "people hate abortion in South Dakota." She finds the hostility toward abortion confusing. "I already have a 6-year-old," she says, looking around the Sioux Falls clinic waiting room. "I know what parenting is like." Her boyfriend of two-and-a-half-years, Jim, 24, a Spartacus-looking construction foreman, seems more understanding of the pro-life position. He's clearly conflicted about Nancy's decision. "It's hard not having a say in the matter," he says. "This week hasn't been easy."

Like many unintended pregnancies, Nancy's is not the result of carelessness but of statistical odds. "She was using birth control," Jim tells me. "Really. She was on the Pill." Regardless, the South Dakota Task Force on Abortion finds that the procedure Nancy wants to get "exploits the mother . . . damages her health . . . and portrays [her] as valueless." Nancy searches the corners of the clinic room for a way to defend herself against the notion she's doing anything but what's best for herself and the child she already has. Finding no answers in the drywall, she gestures toward her boyfriend. He's younger than me," she says. "Only 24. Just starting his life. I'm trying to hold mine together. Really, people should mind their own business." She gets up to go have her abortion. That Nancy and Jim were having sex is undeniably what caused her unintended pregnancy. Leslee Unruh, founder of the abstinence clearinghouse, thinks sex creates many other ills, too-cervical cancer, bad grades, and poor female self-esteem. That's why she was one of the main lobbying forces last year behind both South Dakota's abortion ban and a law to teach school children "that it is the expected standard to abstain from sexual activity until they are married." The abstinence law passed in the South Dakota house of representatives but was never voted on in the state senate. Since 2003, Unruh's organization has received grants from the Bush administration's $113 million budget for community-based abstinence programs.

Unruh, 51, a descendent of Laura Ingalls Wilder, describes herself as "an all-natural type" who raised goats in order to give her five children organic milk. In her youth, Unruh was pro-choice. At age 19, she met her husband, who was pro-life. The couple had many "hot" discussions about the issues, but Unruh didn't change her position until, between her third and fourth child, she had an abortion because her doctor said her life was jeopardized by the pregnancy. "I was given information, but not all the information," Unruh says. "I made a choice-the wrong choice. I'm into taking personal responsibility." The procedure left Unruh deeply bereaved. She turned her regret into action and in 1984 opened the Alpha Center, a pregnancy "counseling" service. Three years later, the center paid a $500 fine after Unruh was accused of offering pregnant women money in exchange for not aborting.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Working with so many pregnant women led Unruh to see what she calls "feminism's new lie"-the myth that women can be as sexually rapacious as men, and as happily promiscuous as Sex and the City's Samantha."When a man has sex, it's just physical," she says. "It's scientifically proven that women get attached. And he who cares the least has the most power." Ergo, virginity, in Unruth's view, is the key to feminine clout.

"I slept around," I tell Unruh. "I don't feel any worse for the wear." (For the record, I'm now a faithfully married 40-year-old with a 6-year-old daughter.)

"You're rare," she says. "Most women who use their bodies have damage, emotionally and physically. But I don't want you to think I think badly of you."

Unruh doesn't think badly of Planned Parenthood, either. She "likes" the Sioux Falls clinic director, Kate Looby, but feels that Planned Parenthood deceives its patients by giving them birth control and abortions. An unintentionally pregnant woman, especially, "needs the truth," says Unruh.

"What's the truth?" I ask.

"That there's a little life there from the moment of conception. But the abortion industry is big business, so they won't tell you that."

I disagree, my uncle Bart Slepian, was an OB/GYN who also performed abortions in Buffalo, NY. I used to write the rare speech he gave. In his last one, he said, "abortion is undeniably the taking of potential life. It is not pretty. It is not easy. And in a perfect world, it would not be necessary."

It's true he made a lot of money doing abortions. Though a relatively cheap surgery (between $275 and $700), abortions don't generate heavy billing costs because they're not covered by some insurance plans. Also, the procedure often takes less than five minutes; in an eight-hour day, a doctor can perform dozens of them. Still, the majority of my uncle's income came from routine gynecology and obstetrics.

On October 23, 1998, my uncle and his wife returned home from Friday-night synagogue services. They were in their kitchen, chatting with three of their four children (ages 7 to 15), when an anti-abortion activist hiding in the woods behind their house fired a rifle into the domestic scene. The bullet hit Bart in the back, shattered his spine, and tore through his aorta before exiting his body through his left armpit-barely missing his 15-year-old son's head. My aunt began CPR, and one of my cousins ran for paper towels to stanch his father's wounds. But Bart was already dead.

A few years before he was killed, my uncle opened his front door and invited the people singing "Jesus loves the little children" on his stoop inside for breakfast. He said if they would stop harassing him and his family (he particularly didn't like them following his kids to school and asking them not to grow up to be "killers like daddy"), they could set up a table inside the clinic where he worked two days a week and pass out pro-life information. He suggested that the real way to stop abortion-which he was all for; no one was more critical of repeat abortion customers than Bart-was to make birth control free and easy to get.

The minister in charge of the "Jesus Loves" choir didn't want to discuss birth control. "They're not interested in solutions," Looby, the Sioux Falls clinic director, tells me. "They only want to talk about abstinence."

Looby, a mother of four, thought she'd seen the anti-abortion movement's most virulent moment when she worked at a clinic during operation Rescue's 1991 "Summer of Mercy." That August, in Wichita, KS, whole families crawled across parking lots, winding up as heaps of "babies" at clinic doors. Children laid down in front of doctors' cars to stop them from driving to work. Protestors closed down every clinic in town. In Omaha, NE, other protestors showed up at a shower Looby's clinic staff threw for her shortly before she gave birth to her first child. "My husband and I decided we had to get out of there," Looby says. She laughs, briefly. "We came here."

I can't even smile with her. After Operation Rescue's "Summer of Mercy" success, anti-abortion leaders began planning a "Spring of Life" in Buffalo. "They'll never drive me out," my uncle Bart told his local paper when he learned of the upcoming event. "I'm not sure what they can do to me that hasn't been done-short of physical violence."

A year later, abortion doctors started getting shot. During the five years between the first murder and my uncle's, I became increasingly aware of the tension surrounding the issue. But for whatever reason, not once did I say to my uncle, who was becoming so depressed he began planning his own funeral, "Gee, Bart, doing abortions seems to be getting to you, and it's definitely getting very dangerous, so why not just quit?" Or just, "Bart, love you." Instead, assiduously marched in pro-choice rallies and considered anyone who opposed abortion a backward woman-hater-not that ever spoke to anyone who was pro-life.Since my uncle died, I've gotten to know a lot of people who are pro-life. Some are decent; others are backward. But, as Yitshak Rabin said, you make peace with enemies, not friends.

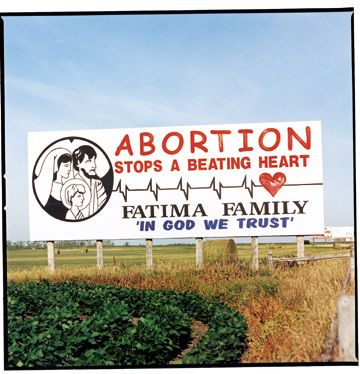

Now, in search of some peacemaking, I climb into my rented Pontiac and take off for South Dakota's capital, Pierre-which locals pronounce "peer"-the epicenter of the abortion debate. At 70 miles an hour on surgical-scar-straight roads, it's a nearly four-hour drive populated with more cows and buffalo than people. Over and over, wavy grassland turns into neat rows of corn and back again. The scene's serenity is marred only by billboards: among the most common are those for a place called wall drug, a pharmacy that sells things like mounted jackalopes (a dead rabbit with deer antlers); and those that herald the evils of abortion ("The gift of life, God's special gift!"), often accompanied by a portrait of what appears to be a smiling fetus, not a born baby, but I'm never sure.

Upon arriving in Pierre, I'm surprised to find state Rep. Roger Hunt, 68, prime sponsor of the abortion-ban bill, in a capitol room chock-full of massage therapists. It seems the state legislature recently passed a law requiring insurance for masseurs, and many don't think that's fair. Hunt gently admonishes them not to cast aspersions so wantonly.

By trade, Hunt is a business and contracts lawyer; serving in South Dakota's legislature is a part-time gig and only pays $6000 a year. He entered politics after retiring from the Navy with no agenda beyond "doing a little good." He got involved in fighting abortion when "some ladies" came to talk to him about abstinence in the early 1990s. Over the past 16 years, Hunt has introduced and supported legislation that, as he puts it, "chips away at Roe v. Wade"-with waiting periods and parental/spousal notification-and launched full-frontal assaults on the right to choose.

Because it's true, tell him that I understand his pro-life position. But I can't fathom why anyone-even people who think virginity until marriage is a worthwhile goal-would support a law that says sex education "may not [discuss] contraceptive drugs or methods" and requires telling students that "engaging in unlawful sexual activity may be a crime punishable by law." In a country where about 80 percent of people have sex before age 20-while the average marital age is 26-such legislation seems downright idiotic. But Hunt thinks teaching teens about birth control is society's way of saying "yes" to fornication, and that if we just stopped talking about sex to kids, a lot of them would quit having it. "When I was a teen," I tell Hunt, "I remember thinking, if I could just stop daydreaming about sex, I'd get so much done. Don't you remember that feeling? "No," he says. Hunt also believes the self-discipline of not having sex translates into the self-discipline of not doing drugs, not becoming involved in crime, and not dropping out of school. He is not alone.

Between 1994 and 2001, the federally funded National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health tracked over 14,000 American teens. The survey found that 21 percent of sexually active teens dropped out of high school, compared to just 8 percent of virgins. Outside America, however, these stats don't hold up: As many teenage Danes have intercourse as teenage Americans, yet their high-school graduation rate is 13 percent higher. And since 1975, Denmark has reduced its abortion rate by 40 percent; ours has increased more than 20 percent. What's the difference? Mainly, that sex education has been compulsory in Danish schools for 36 years, and birth control and emergency contraception (EC) are cheap and easy to get without a prescription: You walk into a drugstore, pay a nominal fee, and don't become pregnant.

It makes me wonder: does accessible contraception function like a seat belt, which protects me but doesn't make me drive crazily - or is it more like the overdraft protection on my checking account, which also protects me while occasionally enticing me to spend recklessly? What i decide is that something is seriously messed up about a country in which sex is as much a predictor of life derailment as drug use or poverty.

Hunt believes one of the reasons his abortion ban finally became law is due to the "scientific findings" from a state-funded task force that studied the issue. the science in the 71-page report, needless to say, is not universally accepted-particularly its controversial argument against abortion in the case of familial rape because incest may create "the brightest person in the family . . . sometimes in the genius range of intellect."

Whether a child comes out smart or stupid, tell hunt, it seems outrageously cruel to make a girl sexually abused by a family member have the baby. The practical issues alone are overwhelming: can she sue him for child support? he stop her from putting the child up for adoption? Hunt is silent for a minute. "From where I stand, there should be no exception. Because what is the greater offense? Taking a life is worse than rape."

Of course, most unintended pregnancies are not caused by vicious attacks. They're the result of kisses that get carried away-and, as Nancy and Jim found out, birth control that breaks.

By the time Nancy returns to Jim in the waiting room later that day, Dr. McCreary has performed 15 other abortions. Kristen Peterson, 28, a South Dakota native and teacher at a local middle school, cleans up after her. Married and super-careful with birth control, Peterson has never had an abortion and probably will never need one. But she's still willing to spend her summer vacation holding the hands of women in the clinic in an effort to stop her state from morphing into a place where she no longer feels at home. A few weeks back, Peterson attended a Planned Parenthood rally. The next day, her photo wound up in the local paper. "That wasn't smart," a school colleague told her.

Why? She wondered. Because I'm pro-choice? Because I'm any kind of political? Because I don't think women should be punished for being sexual beings? "Gosh," Peterson says, "it's getting bad here in South Dakota."

Outside, the late afternoon sun is painfully bright. In the clinic, Nancy looks pale but relieved. Jim just looks pale. They don't seem to notice the protesting grandmas, and the grandmas don't look up from their rosary beads to consider them.

I try to imagine if the world were just a little different-say, one U.S. Supreme Court justice different. What would Nancy and Jim be doing instead of leaving an abortion clinic? .Would they be preparing to give the baby up for adoption? Or would they, like the one time I thought I was unintentionally pregnant, find the notion of someone else raising their child less bearable than aborting it? Would Nancy be on the Internet figuring out how to end the pregnancy herself? Would she and Jim already be arguing over child support and custody? Or would they be down the street, at the state's only Wal-Mart, buying a crib? The last scenario is the one Leslee Unruh and Roger Hunt imagine, and it's one, I suspect, Jim sorely wanted to create. But it wasn't for Nancy. The clinic staff doesn't allow me to probe the depths of why, but I'm guessing Nancy already found out the hard way that a gurgling baby won't fix a troubled relationship, turn a hot-headed boy into a responsible man, or transform a woman into a joyful mother. "I just want to get on with my life," Nancy tells me. And that, for now, is her choice.