La Maison des Femmes

Parisian life can be darker than it seems.

Life as a Parisian woman is often portrayed as filled with couture, culture and haute cuisine. But for some women, that is sadly far from the truth. Here, in collaboration with our partner CHIME FOR CHANGE and in honor of International Women's Day, a startling look at the lives of France's forgotten women.

When I speak of the Paris suburb Saint-Denis, what do you think of? The band NTM. The number 93. Gang rapes. The Stade de France. Metro line 13, packed in the morning. The RER B1. Police violence. The market. The basilica. No-Go zone. The kings of France, as well. I think each person has quite a specific image in their mind of this stigmatized community to the north of Paris. The rate of poverty there is rising to 30% and that of unemployment follows closely at 20%. For me, Saint-Denis was another world. One located 35 metro stations away from my reality. Far, very far from me. And then, overnight, it became my reality.

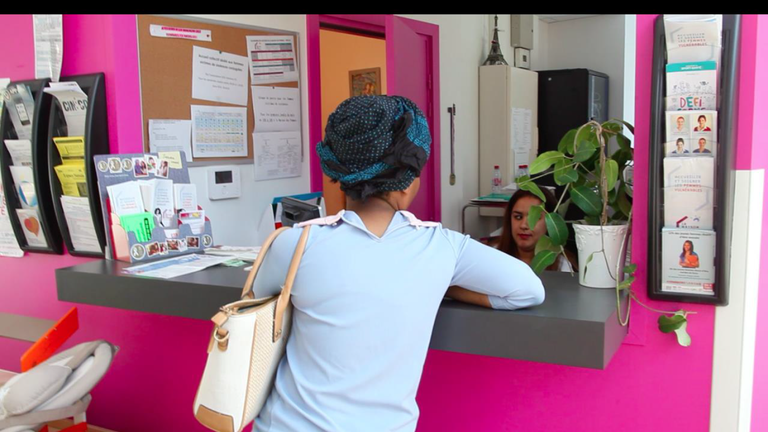

The first time I heard people speak about The Women’s Home in Saint-Denis was at the Ministry for Women’s Rights, where I was training. Ghada Hatem. Above all I remember the first time I heard people speaking about her. Everyone agreed that she was a great doctor. That she had, remarkably, dedicated her life to women, in particular those who are victims of violence. Sheltered in our ministerial offices, we whispered that she was brave venturing where life was most difficult. The title of an article written about her read,“Ghada Hatem, les deux pieds dans la Seine-Saint-Denis” (Ghada Hatem, two feet in Seine-Saint-Denis). Ghada Hatem, she who repairs women. Over time, I have found that the phrase suits her very well. We give her that name because she is among the rare gynecologists in France who surgically repairs women who are victims of female genital mutilation. She also helps women who are victims of rape, domestic or economic violence, and forced marriages. She repairs women who are broken, damaged and destroyed. She repairs forgotten women. Her Women’s Home is a place that welcomes everyone. They take care of victims with great professionalism, but above all with kindness and humanity. Women are offered a place where, in the space of a few minutes, or sometimes a few hours, they can allow themselves a moment to forget how precarious their lives are.

In France, a woman becomes a victim of rape every seven minutes.

I belong with these women. I have been raped several times myself. And condemned to silence, for a long time. Writing this down is nothing less than a political act for me. Every one of us is susceptible to becoming a victim of violence at any moment. I think for me, that’s what becoming a woman is. To accept that, wherever you were born, whether that’s in the 5th arrondissement in Paris, in Saint-Denis, or in Guinea, there is a price to pay for being female. I decided to become a volunteer at The Women’s Home to meet and to help these women. And also to forget my own story. In choosing others, I chose to forget myself; for relief, and of course, through fear. Through fear of saying the words out loud, making it real, and of not having an alternative other than to face it. I have often thought that I would have liked to have such a place. To be heard. To be understood. That is what I want to do for these women – to allow them to be understood.

One week after arriving at The Women’s Home, I met Léa.* The first time I saw her was at her trial, at Paris’ High Court. I had been given the task of keeping her company during the hearing. Léa, at 17 years old, was pressing charges against her brother for physical, moral and sexual violence. She had left her family home a few months before. Since then, she had no other choice but to drag herself between 115 different hotels that were were willing to give her a room for one night, sometimes two. Léa will finish high school at the end of this year. She understands that education is the key to her freedom. She dreams of being free and independent more than anything. So she is trying, as hard as she can, to attend all her classes. When she is not at school, she spends her time at The Women’s Home. There, she has found refuge. A place where she can feel safe. Where people listen to her. Where people believe her. Where people even help her. It is thanks to the staff at The Women’s Home that she has found the courage to report the incident. Only 10% of female rape victims press charges. She is part of that 10%.

She is terrified rather than proud. However, as I sit with her, for five minutes, on a bench in the Criminal Court, I wish I had her courage. To press charges means taking the risk of not being believed. It is taking the risk of being humiliated. Humiliated once again. Humiliated one time too many.

I remember the day I was called to serve as a witness for the Brigade for the Protection of Minors in Paris. I was also 17 years old. A girl from my school was pressing charges against my aggressor. I had never had the courage myself to do so. So, I had to take the role of witness. Called to serve as a witness. Forced to be a witness. It’s the law, Miss. I did not want to be there. I wanted to forget. I wanted to stop thinking about it. How did you find yourself in the bed? But I don’t understand, were you a 17-year-old virgin? Do your friends call you uptight? Could you be precise, please? I don’t understand why you didn’t say no? Why did you not get out of the bed? Why did you not scream? There were plenty of people in the room, weren’t there? Why? I bet that no one has ever asked him, “Why?” Léa’s brother sat a few meters away from her. His wife is there too. It should be known that at the Criminal Court the aggressors, unpunished, contemptuous and proud, are mixed in with their victims.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The four men seated next to us on the bench are called up, one by one, to the bar. All accused. Sexual violence, domestic violence, psychological violence. But, Madame, I swear that I never hit her, I promise you, ask whoever you want, I love her too much for that. But, Madame, I didn’t rape her. In fact, what is rape? Can someone rape their wife?Marriage is sex as well. Eh? No? Don’t you agree? No, Madame, I swear. My children? Ah, no, you must be mad! I don’t hit them! They’re the apple of my eye, Madame! Three hours. Three hours among these men. Three hours seated among these broken, ashamed women, wracked with guilt. Three hours waiting for Léa’s turn, feeling an invading sense of nausea and vertigo. She waits patiently, strong. For a few seconds, her fidgeting hands give away her overwhelming anxiety.

But she stays quiet. I think she is searching for her brother’s gaze. I think she is, once again, trying to understand. Why and how. How could her teenage life have changed like this so dramatically? When her lawyer finally enters the room, it is to let us know that her brother’s lawyer has not shown up and that the hearing will be postponed. Three hours for nothing. This is January. The trial has been postponed until September. How is she supposed to live like this for another nine months? At 17 years old. Without a family. Without an apartment. Without accommodation. Not a cry. Not a tear. She has never broken down. I think it is a survival mechanism. Never let emotions overwhelm us. That would be dangerous. A bit like a tsunami. An unpredictable earthquake.

When I arrived at The Women’s Home, I felt like an idiot for having thought that I was going to be useful. Idiotic and helpless. For a long time, I told myself that it would have undoubtedly been better to leave my fifth-arrondissement-bourgeoisie mindset on the other side of the ‘périphérique’ ring road. That I could not claim to understand these women’s stories. Their pain. I swore to myself that I would never complain again. I reminded myself how fortunate I was. I think that those three hours spent at the Bobigny District Court were a wake-up call. Fortunate? But why exactly? I recognized myself in Léa.

Believe me, that is not easy to write. And yet, it is true. I recognized myself in her. I recognized the coping mechanisms. I recognized the shame. I recognized the feeling of guilt. When I recounted Léa’s story and that of all the other patients at The Women’s Home whose path I have crossed, the reactions of horror were unanimous. But these reactions were almost general statements quickly followed by an, "It’s mad what happens in Seine-Saint-Denis." It's crazy how many women are victims of violence. According to theDepartmental Observatory for Violence against Women, 36,000 habitants in Seine-Saint- Denis between the ages of 15 and 59 have been subject to domestic violence.

This figure is monstrous. But at the risk of disappointing a lot of people, it’s no higher than in other departments in France. No, violence against women is not the privilege of a, let’s say, “African culture.” It is not a privilege of being an immigrant. Nor one of being poor or Muslim. It is quite convenient to think of this societal phenomenon as happening “elsewhere” where it does not concern us, something that we look upon sympathetically from afar.

With all of my 23 years of age and being very fortunate in my apartment in a chic Parisian neighborhood, I can think of so many incidents of rape and sexual aggression that my ten fingers are not enough to count them. But, unlike the patients at The Women’s Home, I have a roof over my head, a fridge full of food to feed myself, a family who will console me. Unlike the patients of The Women’s Home, my future is not filled with darkness. Unlike the patients at The Women’s Home, I have reasons to hope.

Let’s stop denying reality. In France, a woman becomes a victim of rape every seven minutes. One out of six women is a victim of domestic violence. They are all around you, part of your family, in your friendship groups and among your work colleagues. You catch their broken gaze on the bus, on the metro, but also over a family breakfast on Sunday, over a glass of wine with your girlfriends on Saturday evening. They are your mothers, your daughters, your cousins, your sisters-in-law. In Saint-Denis, in Notre-Dame or in Trocadéro.