Little Shop of Horrors

Slick Instagram ads promised the perfect figure at a great price. But for these women, their Brazilian Butt Lift dreams turned into a life-threatening nightmare.

It was humid and foggy on that May day in 2018 when Tyesha Washington arrived in New York City for her surgery. A fashion lover who prides herself on keeping up with trends, the then-35-year-old had been wanting a Brazilian Buttlift, or BBL for short, for years. A single mother of two, she hoped the surgery would make her less self-conscious about her body and feeling older. A friend told her about a clinic called Goals Plastic Surgery that offered discounted rates for the procedure, which isn’t covered by insurance—it would be $5,850, roughly a third of the cost of a BBL at most other facilities. So, Washington saved up the money she earned as a machine operator at MAHLE, an automotive parts manufacturer, and packed a suitcase to travel from Dayton, Ohio, to New York City. She was nervous—but excited. “New York b [sic] good to me,” she captioned an Instagram selfie.

Washington arrived at an unassuming brick building on West 135th Street off Frederick Douglass Boulevard in Manhattan, nestled next to a 24-hour bodega and a dollar store, and across from a bustling Ethiopian restaurant. The office lobby was glitzy, upscale. But after an attendant called her name, Washington was led down a narrow staircase.

Where are we going? she thought to herself as they made their way to a windowless, unfinished basement. The attendant led her to a corner that was sectioned off with partitions that looked like shower curtains. She was given a hospital gown to change into. Then an attendant instructed her to take the handful of pills she had picked up at Walgreens the day before, a mix of Xanax and Percocet, which would render Washington numb—but awake—for the procedure.

When Washington swallowed the little pile of pills, she didn’t know that BBL patients are usually put under anesthesia. Typically, patients meet with their surgeon a month in advance for a pre-op appointment, according to Cat Begovic, M.D., a board-certified plastic surgeon based in Los Angeles, who did not treat Washington. They review the surgical plan together, take measurements, and the doctor answers any questions. The doctor meets them again the morning of the surgery, going over the surgical markings and what they mean. “The OR is warm and comfortable for my patients,” says Dr. Begovic. “There is always soft and calming music, and I am there holding my patient’s hands as they drift off to sleep.”

No one held Washington’s hand in the Harlem basement. She was led to a small room—by a nurse she assumed, though she wasn’t sure—that had a metal medical table and beside it, a tray table holding two large glass canisters that looked like giant Mason jars. These would hold the bright yellow fat—“liquid gold,” as Goals refers to it on its Instagram Live videos—after it was sucked from her stomach but before it was injected into her buttocks.

Then, a man she’d never seen before entered the room and began marking her unclothed body with a pen. The stranger introduced himself as Anthony Ray Perkins, M.D. Washington would never forget his name.

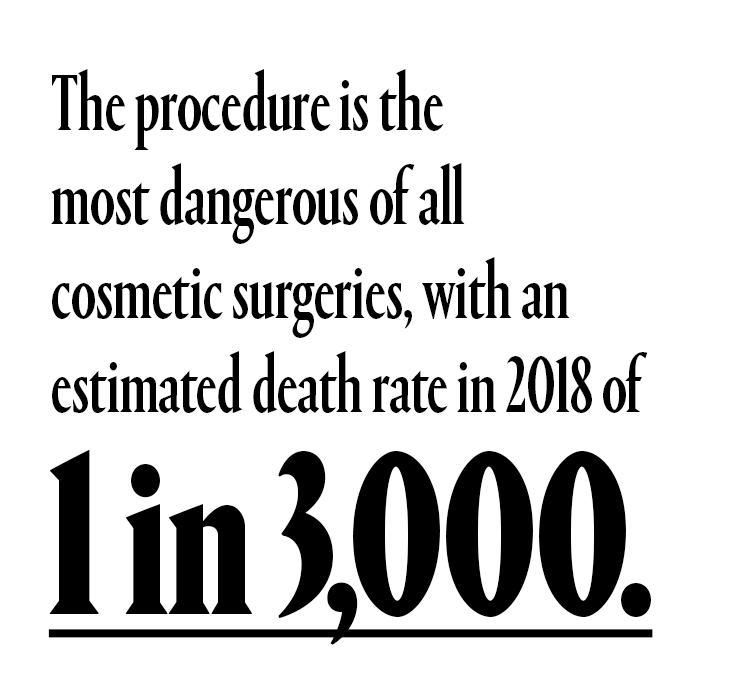

The BBL is the fastest-growing cosmetic procedure in the world. Last year, 61,387 butt augmentations, including implants and fat grafting, were performed in the U.S.—up 37 percent from 2020, according to the Aesthetic Society. During a BBL, fat is removed from the abdomen, hips, thighs, or lower back through tiny incisions with a thin tube called a cannula. This extracted fat is gently washed with an antibiotic solution and healthy fat cells are then injected into the buttocks. It’s a complex surgery; overfilling the butt or improperly injecting it can lead to fat traveling to the heart or lungs, obstructing blood flow, and causing death. According to the Aesthetic Surgery Education and Research Foundation, the procedure is the most dangerous of all cosmetic surgeries, with an estimated death rate in 2018 of 1 in 3,000.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

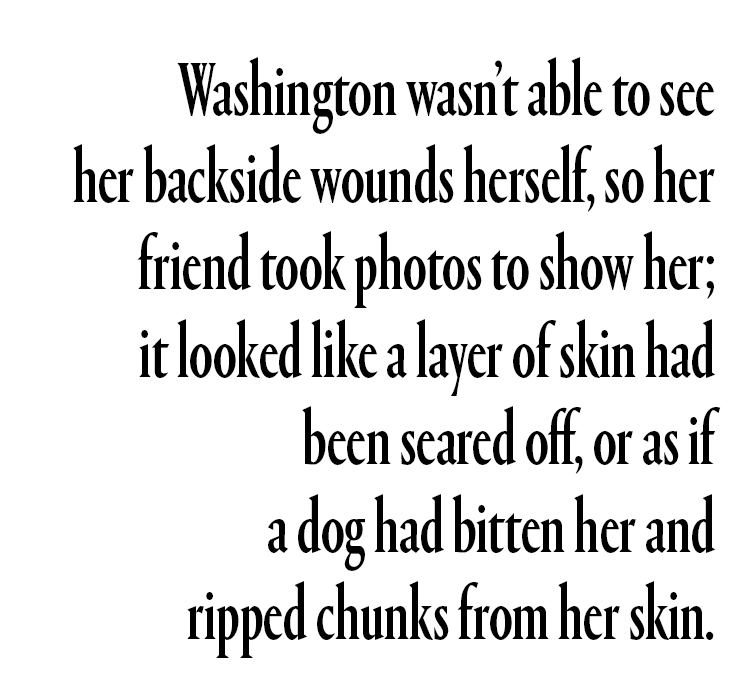

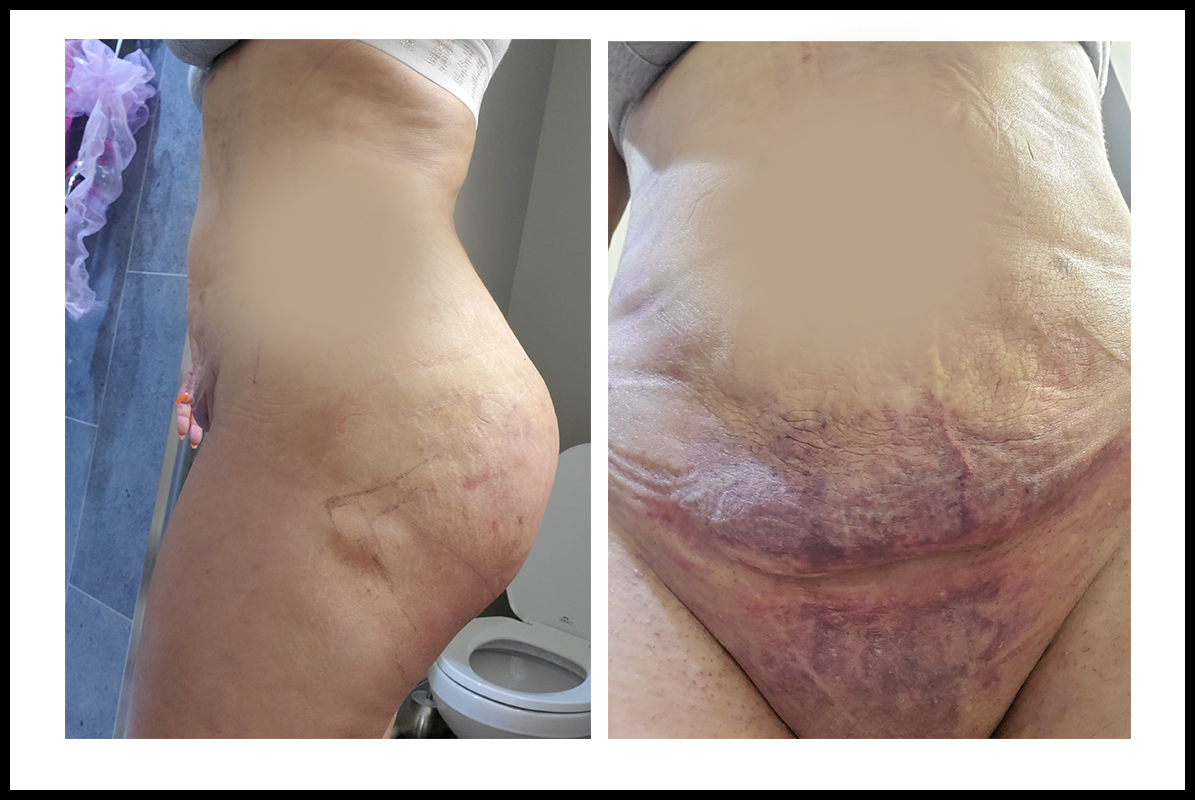

When Washington took a taxi from the Goals clinic to her Airbnb right after the procedure, she was in extreme pain and still woozy from the pills. She figured that the oozing discharge from her rear was a normal post-op reaction. After five days, on May 27, 2018, Washington flew home. She was anxious to return to her job at the factory. But when a friend came over to help her around the house, she noticed something strange about the way Washington was—or wasn’t—healing. Washington wasn’t able to see her backside wounds herself, so her friend took photos to show her; it looked like a layer of skin had been seared off, or as if a dog had bitten her and ripped chunks from her skin. The photos show the incisions leaking thick, murky pus.

Washington went back to work the next day. She had two children to support and couldn’t afford to take more time off. But standing on the factory floor took its toll; on May 30, her pain grew so severe that she checked into Good Samaritan Hospital in Dayton, Ohio, the first of two hospitalizations she would have post-BBL. Doctors diagnosed her with liposuction burns and, a few days later, an infection. The fat that had been injected into her body needed to be suctioned out because it was dying and the infection was spreading. She had a remedial surgery on June 20 at Miami Valley Hospital where she was attached to a Vacuum-Assisted Closure device (VAC), a drainage tube and portable pump that heals traumatic wounds by pulling out fluid and bacteria. Wound VAC is a painful way of healing from the inside out—it was even more painful, Washington says, than being awake during the BBL. The corrective surgery left her with a gaping hole in her right butt cheek, and for five months afterwards she had to bring her pump everywhere she went.

It was then that Washington began obsessively researching her surgeon, Dr. Perkins. She discovered that he has a history of malpractice litigation against him—including three cases currently active in New York. (Dr. Perkins did not respond to request for comment about Washington’s surgery or the litigation he is currently facing.)

As of press time, Perkins is one of at least 15 doctors currently employed by Goals Plastic Surgery, a practice that has operated since 2016. But the story of the Goals basement butt lift goes back three decades.

In the late '90s, Sergey Voskresenskiy, M.D., a medical school graduate of Azerbaijan State University, came to New York. He and his wife, Ella, made their home in Mill Basin, Brooklyn. In 1999, Dr. Voskresenskiy began his medical residency at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Ella worked at the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, also known as the Claims Conference, a reparations foundation for Holocaust survivors. Despite her modest job, Ella was known by friends and coworkers to indulge in designer clothes and take lavish trips to Europe. She owned two homes in Mill Basin, Brooklyn, and one in the Poconos, Pennsylvania. After her husband completed his residency, she opened a medical clinic for him in Brooklyn in 2006.

The Voskresenskiys had a comfortable life. That is, until October 2011, when the FBI arrested Ella for conspiring to defraud the Claims Conference of $57.3 million. In an FBI court deposition, one lawyer testified that Ella had made fraud “a full-time job.” Ella pled guilty to fraud in 2013 and served a federal prison sentence of 36 months, a fraction of the maximum 40-year sentence she faced.

Ella was released from federal prison in May 2016. By then, Dr. Voskresenskiy was making changes in his career. Though he was trained as a pediatrician, he began performing procedures that would almost never be seen at a pediatrics office: cosmetic surgery. The market was ripe for it—Americans spent more than $15 billion dollars on cosmetic procedures in 2016. Dr. Voskresenskiy registered this new practice as Allure Clinic, where he offered BBLs, breast augmentation, and tummy tucks—procedures high-end Upper East Side plastic surgeons provided, but at half the price, and he offered payment plans. Ella became his “supervisor for advertising and social media,” helping brand her husband online as “New York City’s top plastic surgeon.”

The Allure clinic got off to a rocky start. In 2017, the office manager and receptionist at the original outpost in Brooklyn filed a lawsuit against Voskresenskiy, claiming unpaid wages and overtime. (The lawsuit ended in a settlement, with the practice paying a total of $35,000 in damages.) Plus, there was already a New York practice named Allure, run by surgeons in Staten Island. Between confusion with this other practice and the lawsuit, Voskresenskiy needed a fresh start.

In December of that year, he renamed Allure Goals Plastic Surgery. The location stayed the same, but the practice added an additional office on the third floor of 100 Livingston Street in Brooklyn. Dr. Voskresenskiy now went by a sleek new name, too; he legally dubbed himself “Dr. Voskin.”

By 2018, the West Harlem clinic where Washington had her procedure had opened. This office would draw patients in numbers far surpassing those of the Brooklyn locations. In a May 2020 court deposition from an employee class action suit against Dr. Voskin, he said the Harlem facility had on average “300, 400 [patients] a month, something like that,” while the Brooklyn office had between 100 and 150. Dr. Voskin described the practice as “not really super medical; it is cosmetic.”

And he said of his patients: “We will call them also customers.”

Turns out, Dr. Voskin’s booming business was made possible by a lucrative loophole: All medical doctors can legally perform cosmetic surgeries, regardless of training.

“Back in the early ’80s, you couldn’t say you were a plastic surgeon unless you were a board-certified plastic surgeon, or trained as a plastic surgeon,” says John E. Sherman, M.D., a board-certified plastic surgeon practicing on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Board-certified plastic surgeons train for six to eight years at an accredited institution, pass extensive oral and written exams, and must continually be re-certified. However, board certification is a voluntary accomplishment; there are no state-mandated requirements that measure competency. Doctors don’t need any plastic surgery training to call themselves plastic surgeons. Dr. Voskin’s website states that his surgical training consisted of “various cosmetic surgery seminars around the United States.”

Any doctor can easily register private plastic surgery practices as Office-Based Surgery (OBS) businesses, places where medical procedures are done outside of a hospital or surgery center. Podiatrists, for example, sometimes work from OBS facilities. In fact, 60 percent of all surgeries were performed in OBS facilities in 2017, compared to 10 to 15 percent in the early ’90s, according to research published in the medical journal Annals of Vascular Surgery.

When I requested documents from the Department of Health relating to Goals through the Freedom of Information Act, the DOH responded that “the facility that is the subject of your request is an Office-Based Surgery (OBS) practice that is not accredited by the Department of Health. As such, the Department does not maintain [its] records.” Goals’ website, however, listed the practice as accredited as recently as May 2022 (that claim has since been removed); if it were, it would be rigorously audited by the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC). When I called the AAAHC office to confirm, a representative said Goals is not accredited by them and that their legal team would investigate the false advertising.

For Dr. Voskin's purposes, accreditation doesn’t seem to matter. OBS facilities don’t have to be accredited if their procedures are considered “minor.” In New York State, “minor” is defined as a procedure that can be done “with minimal sedation.” Goals often uses a combination of Xanax, Percocet, and Lidocaine to numb patients, who, like Washington, remain awake. The only specific procedure addressed by the law is liposuction; in OBS settings, doctors can only remove half a liter of fat.

Thus, a Brooklyn pediatrician was legally able to open a practice that designated the most dangerous cosmetic procedure in the world “minor.” But Dr. Voskin's clinics also advertise a “Mega BBL,” described as removing “up to 10 liters of fat.” Goals posts BBL ads on Instagram targeting patients with higher BMIs, up to 45. According to Dr. Begovic, a patient’s BMI needs to be around 30 or below to ensure a safe procedure.

Dr. Voskin did not respond to multiple requests for comment about his medical training, the ongoing lawsuits against him and his practice, or Goals’ medical, business, or marketing practices, including potential exploitation of legal loopholes and inaccurate claims of accreditation.

There’s no regulatory body for social media, says Dr. Sherman, much like OBS plastic surgery itself: “Zero. What’s happened now is that greed has taken over.” In a 2009 academic article, anesthesiologist David Wax of New York’s Mount Sinai School of Medicine warned of the “new frontier” in surgery, likening OBS to the “wild, wild West” of healthcare. He wrote: “The rapid expansion of OBS was not accompanied by a parallel expansion in oversight by government, healthcare organizations, or peer review to maintain quality of care that exists for hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers.” The result was, in his words, “a surgical free-for-all.”

In 2019, 26-year-old Maiya Felix made an appointment for a BBL at the Harlem Goals office. Her mother, Edna Felix, describes her as spirited and fun-loving, always doing makeup for her friends and planning events, like the party she was throwing for her daughter Jaelah’s fifth birthday. Felix worked a demanding job as a Youth Counselor at St. John’s Residence for Boys, a foster care agency, earning $16 an hour. She often didn’t get home until after 11 at night. Edna helped out with Jaelah while Felix was at work. The three lived together in an apartment in the Seth Low housing project in Brownsville, Brooklyn.

Felix had been self-conscious about her body for years, after gaining weight post-childbirth and working long hours. On her surgery date, July 16, 2019, she saw Goals contractor Maria LoTempio, M.D. After the procedure, she went back home to her family in Brooklyn.

Court records for ongoing litigation allege Felix was not examined before the procedure, that she did not have a proper consultation, that Goals failed to obtain her medical history, that her BMI was too high for a BBL, and that Dr. LoTempio removed 6.3 liters of fat. The records also allege that Felix was prematurely discharged, without a follow-up plan.

On July 18, Felix was admitted to Brookdale University Hospital with a blood clot and a pulmonary embolism. She died the next day.

In legal documents responding to the wrongful death suit filed by Felix’s family, Goals denies culpability, stating that independent contractors such as Dr. LoTempio sign an agreement that indemnifies the practice. Neither Goals nor Dr. LoTempio responded to Marie Claire’s requests for comment by press time.

Edna now cares for Jaelah full-time. She says nighttime is the hardest, especially during the late hours when Felix used to get back from work. “Some nights I still wait up for her to come home.”

Like Felix, Samantha Santana was a young mom when she underwent a BBL at Goals. Santana, 25, lived in the Bronx, where she was born and raised and worked as a dental assistant. She had a son, Ryan, who, like Felix’s daughter, was 5 years old. Santana researched her assigned doctor for months prior to her procedure and was active in private social media groups for “Goals Dolls” (as women who have undergone surgery at the practice, or are considering it, call themselves). On August 27, 2020, Santana posted some hesitancy about her upcoming procedure: “Ladies! A lot of people are calling this place a chop shop saying they felt everything during the surgery. I think that’s so messed up like who wants to feel that pain … Definitely making me nervous!”

But that hesitation seemed to wane. On September 3, 2020, she posted that her surgery was confirmed for later that month: “I am the happiest girl ever right now. Everyone have a beautiful perfect day cus I’m sure having oneee [sic].”

I meet Santana’s family at her sister Aliyah Santana’s home in the Throgs Neck neighborhood of the Bronx. Aliyah leads me upstairs to her unit, past her two small children playing and giggling in the hallway, into a sitting room filled with family photos. Santana’s mother, Nancy Negron, sits on the couch, her hands clasped tightly in her lap.

Negron, a liaison at Montefiore Medical Center, never wanted her daughter to get the surgery. “I was always against it, but at the end of the day, you’ve got to support them. They’re adults already.” She says Santana had always struggled with self-image. “If she had a pair of sneakers, and somebody was saying, ‘Those are ugly sneakers,’ she would never wear them again,” Negron says. “It was very challenging, her growing up and being that way because she was just not happy with herself. I tried my best.” Before her surgery, Santana had excitedly sent her mom pictures of a Goals surgeon performing a BBL on a friend with the message: “omg im [sic] gonna look so good.”

Aliyah remembers her sister thinking of the surgery as a new beginning. “She felt it was holding her back, not having the body that she wanted, other people constantly making fun of her.”

“One thing she was proud of was being a good mom,” her mother says. Aliyah agrees. “And she didn’t even get a chance to see him graduate, nothing.”

Santana died in the emergency room at Jack D. Weiler Hospital on September 24, 2020, the morning after her surgery. Her death certificate shows the cause to be a toxic combination of Oxycodone, Alprazolam (Xanax), Lidocaine, and Fentanyl—all of which are used at Goals.

The next day, Goals posted an Instagram story that read: “Goals is aware that one of our patients has passed away off of our premises.” Santana’s family says they never heard directly from Goals. They can’t be sure who her surgeon actually was; on Santana’s contract, where the surgeon is listed, it reads in parentheses “may be changed at Goals’ discretion.” The clinic has a history of withholding information on procedures and physicians from patients. At least five women have filed suits against the clinic for their medical records. Patients in New York are entitled to their records for six years after a procedure, yet court documents show Goals evading those requests, sometimes even denying the patients were ever theirs at all. (Representatives for Goals did not respond to requests for comment about these suits or Santana’s procedure.)

Just a few days after Santana died, the Dolls community was talking about a Snapchat video circulating of a young woman named Ché Mcintosh. In the video, Mcintosh lies face down on a medical table, her long, thick hair tied up in a surgical cap. This is all she wears. The room is narrow, just fitting the small table, with blue-tinged fluorescent lights flickering overhead—the operating table at Goals. Employees reported that the video was taken by an assistant (many surgeries are filmed at Goals; in the contracts patients sign, they must agree to being filmed for social media), and that a whistleblower leaked the footage to social media.

“Are you ready to go home?” a peppy male voice asks her, presumably her physician, Thaddeus Boucree, D.D.S., M.D., or an assistant. “Yesss,” she slurs, her eyes blank, before her head falls limp over the table. The videographer cuts to her bottom, swollen and bruised, engorged into a shape rarely given by nature: a BBL.

Mcintosh was a dancer at Club W in the Bronx. As a side hustle, she was building her own holistic herbal wellness business, which she hoped would one day provide a full-time job. For now, her looks were the basis for income. Surgery would be an investment in herself, for her work as a dancer at a club where men expect to see Instagram bodies in the flesh.

She never had a chance to show off her transformation. Mcintosh died the night of her surgery. She was 27 years old.

McIntosh’s toxicology report shows the same combination of drugs as Santana’s. In the days following the deaths, the New York State Department of Health’s Office of Professional Medical Conduct suspended Dr. Boucree’s license. But the surgeries didn’t stop. Instead, they were moved to a new location: a storage room in a condo building at 158 East 100th Street. Property records show that on October 15, 2020, Dr. Voskin registered an LLC that was used to purchase the unit. Goals freelancers continued to operate in the space until at least April of 2021, appointment emails show. Marie Claire reached out to both the Office of Professional Medical Conduct and Dr. Boucree about the investigation and deaths; neither responded.

Marion Conde, a medical malpractice attorney in New York who represents women in cases against negligent doctors, says the lack of rules in cosmetic surgery coupled with massive demand for this certain type of curvy body has created “the perfect storm” for medical malpractice injuries. She warns that the situation is bound to get worse. “I truly believe if men were the victims, there would already have been a national dialogue with movement afoot for the passage of sterner regulations,” she says.

Medical malpractice investigations are long and arduous, and while doctors are under investigation in one state, they can often still practice elsewhere. Mcintosh’s non board-certified doctor has been under investigation and restricted from practicing in New York since October 9, 2020. But as of 2022, Dr. Boucree is practicing at a dental office in New Jersey.

It was a Goals billboard in Brooklyn that caught Amy Castro’s attention. Castro is a bar manager and former dancer who wears a piercing on her lower lip and thick winged eyeliner. She’s sharp-tongued, switching between English and Spanish when she’s angry, and she loves riding her motorcycle through Harlem, even on the coldest days.

Castro had been researching BBLs when she saw the Goals ad. She planned to travel overseas for her surgery, but now, she thought, maybe she could get her work done locally, right in her neighborhood. When she called to book an appointment, she was told there would be a nonrefundable booking fee (as high as $500 of late) before seeing a doctor, which seemed strange to her. Typically patients pay a fee for a consult, but with a clinician. “The surgeon should have the ability to give you the consultation on what they’re going to do—and also decide not to do it,” in cases where operating could be dangerous to the patient, Dr. Sherman says. At Goals, the initial consultation is not with a medical professional, but with a “patient coordinator,” a non-medical employee who arranges the surgeries. Patients don’t see a doctor until the day of the procedure. (In the employees’ class action lawsuit deposition, a patient coordinator testified she earned $100 for each patient she closed on; Dr. Voskin denied this, saying the bonuses are “random,” but also that there are quotas the coordinators must hit.)

Castro ultimately traveled to Colombia for her BBL; there, the surgery has a reputation of being cheaper and more established than in the U.S. But when she came back, she couldn’t seem to escape Goals. The advertisements were everywhere online. She knew women in her community who were getting BBLs at Goals—and they felt they looked worse afterwards. On January 13, 2021, Castro posted an hour-long, teary Instagram live recounting her friends’ bad experiences, urging viewers to report the clinic. The video went viral, netting more than 20,000 views. In the comments, people told their own stories of botched procedures at Goals.

The more women who reached out to her, the more Castro made her crusade against the practice a full-time endeavor, posting daily videos on how to find a board-certified surgeon, walking viewers through what a procedure should look like from her experience and research, encouraging women who had procedures at Goals to reach out to the local news. “From the moment I get up to the moment I go to sleep, I’ve been working on this,” she says. She even broke up with her boyfriend—she simply couldn’t focus on anything but Goals.

Castro can speak freely, but women who have undergone procedures at Goals feel silenced. Patients are required to sign an initial surgery contract before going under the knife, affirming that they won’t post negatively about Goals online before speaking with the practice first. In the contract, Goals lists the fine for a bad review at $10,000. Dr. Sherman and Conde say this is not standard medical practice, and very likely unenforceable, yet the majority of women who spoke to me and hadn’t pressed charges referred to this contract as a primary reason for not speaking out.

Goals has brought litigation against women who infringed upon the clause. One patient, Jennifer Ramirez, was sued in New York’s supreme court for criticizing the practice on her Instagram account in 2018. In 2019, Isis Richardson, the owner of the popular blog Surgery411 and a former social media employee of Goals, was also sued for posting a photo on her Instagram account of Dr. Voskin with the caption: “Pediatrician makes millions posing as a NY plastic surgeon.” The court dismissed the cases, but the actions exacerbated fear of retaliation among victims.

“We see all these cases coming to our hospital with complications,” says Dr. Sherman, who is also a faculty member at Weill Cornell Medicine. “We ask, ‘Where was it done?’ And it was done somewhere in Manhattan, by someone who’s not even a plastic surgeon. Unfortunately, this [increase in botched procedures] has exploded with the advent of social media.”

Perhaps nothing has helped Goals grow more than the tiny devices in our pockets, windows into everything we could have, everything we could be, everything we could look like. “I should’ve done more research,” says Vera Ibrahim, a 47-year-old mother from New Jersey, who had a BBL surgery at Goals in September 2020. Her voice is quiet. She had followed the practice on Instagram for years. “I was going by people’s results, their ‘before’ and ‘after’ photos, but I didn’t do any research.”

Like most of the women I spoke with for this story, Ibrahim chose Goals for her BBL based on its social media presence. The practice posts videos, live streams, and advertisements constantly, in English and Spanish. Its Instagram grid features neatly aligned rows of large, perfectly round rear ends, ones that look like those that dominate popular influencers’ feeds, their bodies oiled up for the after photos, faces cropped out. Sprinkled within the butt transformation photos are memes; one is a photo of Kim Kardashian looking stunned. The caption: “When your man asks if you really need a BBL…” Part of Goals’ marketing plan seems to include “brand ambassadors,” who live-stream procedures at Goals in exchange for free or discounted services, like influencer Donna Lombardi, who has 1.9 million followers on Instagram, where she describes herself as a Goals brand ambassador. (Lombardi did not respond to request for comment.)

Interspersed with the transformation shots and influencer testimonials are discount codes and gimmicky advertisements, like the Tax Return BBL, which encourages women to use the money they get back from the IRS to pay for the procedure.

A former Goals social media employee, who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation, tells me she worked under Dr. Voskin’s wife, Ella. “Ella is the mastermind,” she says. “When it comes to social media, she’s lowkey a genius.” When I ask about Dr. Voskin, the employee says, “He’s just a surgeon—like, he just does surgery. He doesn’t really run it.” (Ella Voskresenskiy did not respond to request for comment by press time.)

As the Harlem location’s success boomed, Dr. Voskin and Ella needed a fleet of freelance surgeons, like Dr. LoTempio and Dr. Boucree, to keep up with demand. One freelancer, David Shokrian, M.D., (who, like Dr. Perkins, is trained in plastic surgery but is not board-certified) made $1,000 per surgery performing the BBL procedure three or four times a day, up to five or six days a week. In one ongoing lawsuit, a woman accuses Dr. Shokrian of amputating her clitoris during a botched labiaplasty. Dr. Shokrian did not respond to our request for comment, but according to court documents, he claims that any negligence was the responsibility of the Goals practice, not him.

Like Dr. Voskin, some freelancers are not trained in plastic surgery; one, for example, is a urologist. Some are impossible to research, as they use only a last initial in marketing materials, instead of a full name. Others have dubious pasts. Peter Vail Driscoll, M.D., was disciplined by the Medical Board of California for failure to maintain adequate records, failure to obtain informed consent, and repeated negligent acts. In California, he received 35 months probation, restricting him from engaging in the solo practice of medicine, and mandating him to take ethics, medical record keeping, and education courses. He failed to do so and was forced to surrender his California license in January 2020. He works at a Goals location in New Jersey as of July 2022. (Dr. Driscoll did not respond to requests for comment.)

No tragedy, scandal, or lawsuit seems to have lasting impact. Just a few years earlier, Dr. Voskin’s family faced eviction from their Mill Basin house; by 2019, they owned a $5.2 million condo at 200 Riverside Boulevard, formerly Trump Place, and two other apartments in Manhattan worth $3.6 million and $1.5 million.

“It’s a gold mine,” says Andres Beregovich, a Florida lawyer who specializes in laws around plastic surgery. “Anybody can open up a surgery center. And then what you’re doing is using the physicians as independent contractors in order to escape the vicarious liability argument—or at least be able to defend against it.” Beregovich notes that the use of independent contractors shields the clinic owner from liability in the event of malpractice. “If something should ever happen to you that was negligent, we’re not together,” is how he describes the owner’s mentality. Beregovich’s firm represented patients in a case against the owner of a Miami clinic where at least a half dozen women have died from cosmetic procedures. That clinic has continued to operate under different names. “Crooks,” Beregovich calls them. “Educated crooks are capitalizing on vulnerable women.” He says his clients tell him they’ve been treated like cattle “and they really are, because all they are is a dollar sign.”

I approached Dr. Voskin for comment on Beregovich’s claim regarding his use of freelance surgeons as a shield, as well as the various statements made by employees, patients, and critics about Goals’ questionable business and medical policies and techniques and the resulting impacts—including that at least three Goals patients died shortly after undergoing surgery at his facilities. I received no response.

Four months after her BBL in 2018, Washington, the single mom from Ohio, filed a medical malpractice suit against Dr. Perkins and Goals Plastic Surgery. After a legal battle spanning two-and-a-half years, and despite the dozens of photos and hospital records, in March 2021, she lost her case. The reason: In June 2018, she sent the hospital records from her remedial surgery and post-op photos, along with a refund request, to Goals. The practice obliged, but on the condition that Washington sign an agreement releasing Goals from any liability. She signed on June 29. She needed that money while she was out of work. The lawsuit shows she later claimed she was on Oxycodone when she signed the document and not clear in judgment. The court denied the reasoning and ruled Goals inculpable, with a judgment that said: “Read the fine print before signing a contract.” Dr. Perkins received no penalty.

Goals vigilante Castro’s DMs are flooded with stories from women who never pressed charges and might never do so. “Listen,” she says to me, “a lot of these females are sex workers. A lot of these females are moms. A lot of these females don't want their families to know that they're getting surgery; they're embarrassed to admit that they got surgery, or they're too scared to speak up. So, it's harder than what anybody thinks. People are like, ‘Why don't they just speak up?’ Or ‘Why don't they just get a lawyer?’ It's not that easy. It's hard, and a lawyer is expensive.”

Washington, who has watched the practice continue to grow, doesn’t want to give up. Last year, she reached out to a lawyer in New York representing Felix’s case in hopes of finding other victims to form a class action suit against Goals.

But many women have little faith they can win the fight. “It’s like everything has to be to the extreme, or everything has to be to somebody wealthy for them to do something,” Santana’s sister Aliyah says. Negron has lost all hope in the system. After crying all day with patients and their families as a customer service specialist at Montefiore hospital, Negron goes home and cries for her daughter.

And Dr. Voskin? In 2020, he and his wife bought an $8 million waterfront property in Miami—a city notorious for lax cosmetic surgery laws and prolific clinics—under an LLC. In March 2021, they used another LLC to purchase a $3.3 million, 14,600 square foot mansion in Atlanta, where they opened a new Goals outpost.

As of May 2022, there are 11 Goals locations across the country, not only in New York, but in Georgia, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Florida, and Maryland. While the practice is still not accredited, in September of 2021, it earned an accolade perhaps more profitable—verification on Instagram, where the practice now has 1.2 million followers. Goals sent out a press release touting the blue checkmark: “[Goals] couldn't have done it without their countless patients, fans, brand ambassadors, employees, and of course, the #GoalsDolls!”

“In today's digital world,” it says, “social media is king!”

This piece will be updated if responses to requests for comment are received from any of the entities or individuals named.

Meghan Gunn is a writer living in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in Newsweek, Narratively, GEN and Sojourners among other publications.