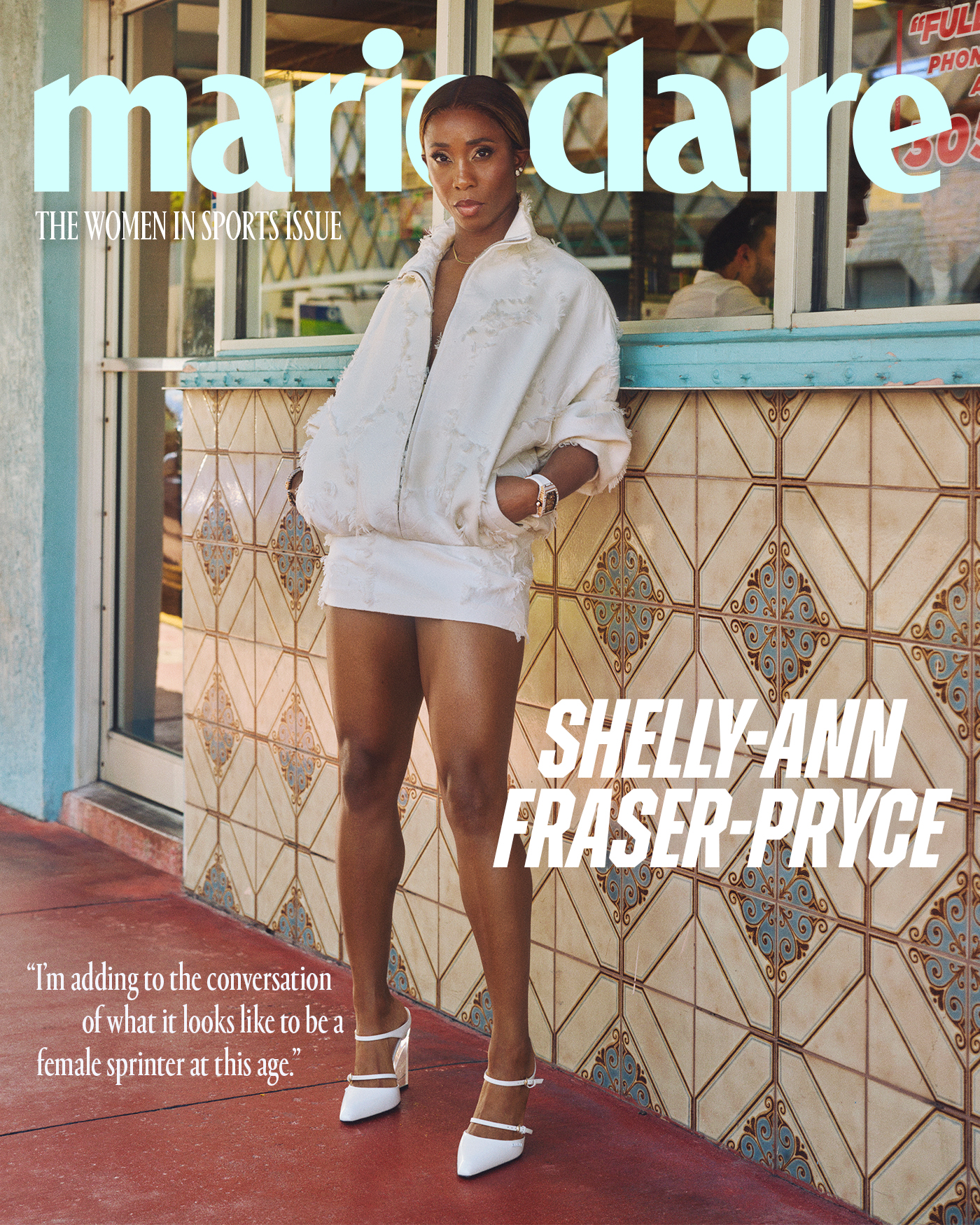

For Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, This Is More Than a Victory Lap

The Olympic medalist and world track champion has been the one to catch for nearly two decades. After withdrawing unexpectedly from the Paris Olympics in 2024 in what was supposed to be her last race, the star sprinter has emerged for one last season—and to explain what really happened.

A physical therapist, wearing all black, is focused on the right hamstring. Her hands knead the muscle, thumbs pressing into the skin with both force and care. She works her way down to the calf, then the achilles. Outside is the loud thrum of Monday afternoon traffic in Jamaica’s central Kingston, but inside the back room of the unassuming space, the energy is quiet, focused.

The calm mannerisms of the staff, the relaxed vibe of it all, belies the reality that facedown on the treatment table is Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce. An eight-time Olympic medalist and five-time 100-meter world champion; one of the biggest names to ever come out of Jamaica, a country that prides itself on its track and field stars.

That Fraser-Pryce is preparing her body to run again belies another reality. The last time most people saw Fraser-Pryce, it was early 2024, and she had just announced her plans to retire after the Paris Olympics. She wanted to spend more time with her son Zyon, who is now 7, and her husband Jason. Going into the Games, Fraser-Pryce’s sprint times were lightning in a bottle; there was a palpable buzz building around her chance to take gold, in what would be a perfect finish to a legendary career.

But then the unexpected happened. On the eve of her semi-finals race, Fraser-Pryce, suddenly and without much explanation, pulled out of the Olympic competition, seemingly ending her run as a track star.

At least, that’s how it looked. Until mid-May, when Fraser-Pryce, now 38, emerged confidently back on the world stage at the Wanda Diamond League where she ran a blazing 100-meter time of 11.05 seconds (notably faster than 25-year-old Sha’Carri Richardson’s season opener of 11.47). Then in June, she officially qualified for the World Athletics Championships in Tokyo, which she’ll compete in come September. A race that Fraser-Pryce says will be her last.

If it sounds like a comeback or a do-over, to Fraser-Pryce, it’s none of those things. She’s a competitor with more in the tank. “I love where I’m at in this journey,” she says, sitting up after finishing her physical therapy. “I’m not saying it’s easy, because it’s not. You’re going to have challenges. But when I look in the mirror, I see a strong, fearless woman who’s about to do the impossible.”

The origin story for many athletes often begins with an annointment—that of the young kid with a natural gift. For Fraser-Pryce, that was certainly true. What started as 500-meter runs to the school bus quickly turned into her making the track team at Wolmer’s Trust High School for Girls in Kingston, where she qualified for the ISSA/Grace Kennedy Boys and Girls Championships (the Super Bowl of track and field in Jamaica) at 13 years old. At 16, she won them.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

To truly go the distance, though, Fraser-Pryce knew she’d need more than natural abilities. “There’s no success without hard work, even if you have talent,” she says. “I realized that if I worked hard, stayed committed and passionate, then I could really go places.”

Going places, opportunities—that was part of the calculus behind Fraser-Pryce’s drive. She grew up in Waterhouse, a Kingston community with one of the highest crime rates on the island. The tenement house she lived in had seven separate single units, each occupied by a relative, all connected by a yard where her grandmother would plant rosemary and tomatoes. She shared a bed with her two brothers and mother, who worked as a street vendor. There wasn’t an inside bathroom, but Fraser-Pryce remembers, with a wide grin, that there was always an abundance of laughter. So many days spent playing with her cousins in the yard, knocking and making music with paint cans and drums.

Versace dress; Miu Miu sunglasses; Gianvito Rossi shoes; Talent's own bracelets

It was on her first-ever trip out of the country to compete in Pennsylvania that Fraser-Pryce met Jeanne Coke, of Wolmer’s Old Girls’ Association, and who would ultimately be integral in helping her reach the next level. Coke began sending the aspiring Olympian funds to cover things like school, books, and lunch. She wasn’t used to this kind of generosity without wanting something in return. “Being from an inner city, I don't like taking stuff from people because you take things and they require something of you,” Fraser-Pryce says. “But her intentions were pure. She’d call and make sure everything was okay. She saw what I could be from the beginning."

Things took off from there. Winning titles at the Under-18 Championships and then on the international stage: medaled at four consecutive Olympics, first Caribbean woman to win gold for the 100-meter, third fastest woman of all time, the list goes on. She earned the nickname “the Pocket Rocket” for her small stature and impressive speed. And she earned endorsement deals too, including from Nike. “Her dedication to her craft is almost incomparable,” says Tanya Hvizdak, vice president of global sports marketing at Nike. “She thinks differently about how she trains, and that has afforded her the ability to do this for such a long time. Shelly will run through walls when she’s committed to getting something done.”

She’s certainly gone places, but in other ways, has never left home. Fraser-Pryce still goes to Waterhouse every weekend to attend church; she shows up at her son’s school and flies past the other parents at races on sports day (you’ve likely seen the viral videos).

The particular Sunday that I arrived in Kingston in May, there was a ceremony in Fraser-Pryce’s honor as the mayor renamed Ashoka Road, the street she grew up on, “Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce Drive.” When they unveiled the sign, there was a misspelling in her name. You wouldn’t have known by her behavior, wearing a wide smile, waving to cameras and onlookers. That she was more concerned with how everyone else felt about the mistake than the mistake itself is a tell of who she is; humble, with a steadiness of spirit that is fascinating for someone always in motion. (The sign was fixed the next day.)

“All of those years I’d walk that street at six o'clock in the morning, often with my head low,” she says. “Sometimes I didn't have any breakfast. I was always quiet. That day, I stood on that same street with my head held high, alongside my son, my husband, and a whole host of my family.”

This isn’t the first time she has been honored by the island where track and field is a thread of unity in the fabric of its culture. Just four months ago, Fraser-Pryce was awarded the key to the city of Kingston, which she celebrated by making a $50,000 donation to her high school. She’s big on giving back, hoping to provide opportunities she didn’t have to young students through her Pocket Rocket Foundation. “I know what it feels like to have the dream but lack the resources,” Fraser-Pryce says. To date, the Foundation has provided nearly 100 academic scholarships to students across dozens of Jamaican high schools.

Blumarine dress; Dior earrings

Wearing an orange and white top, jeans, and a Richard Mille RM 07-04, Fraser-Pryce orders a frozen passion fruit lemonade. I follow her lead and do the same. It’s a late May evening, and we’re sitting under a pink and white umbrella at one of her favorite Kingston restaurants, Fromage. A spot that’s nestled next to a popular night market where local vendors sell craft honey and frozen popsicles; Bob Marley and Lauryn Hill’s “Turn Your Lights Down Low” is playing over a speaker in the center of the square.

Within minutes of sitting down, a woman stops to praise Fraser-Pryce. “I’m so proud,” she says. “You make Jamaica proud, you know?” Holding the menu and deliberately resisting eye contact, Fraser-Pryce smiles timidly, and says thank you. Interactions like this would happen twice more during our 90-minute conversation. A friend of Fraser-Pryce’s, Aisha Praight Leer (a two-time Olympian herself) describes the beloved athlete as “Jamaica’s Michelle Obama.”

Our talk turns to the Olympics. After pulling out of last year's Games, Fraser-Pryce didn’t provide much context. There were headlines about an injury, but that didn’t seem exactly right. “Last year was very hard for me mentally and physically,” she says. “I’ve always done it for the flag and showed up to do it for my country. But what happened in Paris, that was a ‘me’ decision.”

As she tells it, after cruising through the 100-meter heats at 10.92 seconds, she was basking in what she calls “that final Olympics feeling. She adds: “I felt good. I was just ready to let it all go, no fear.”

But when she arrived at the gate at Stade Annexe for her next run—the same gate she had entered the day before—she was denied access. “They tell me that the gate is closed, and I’m like, Well, the track is like right there and I used the gate yesterday. They tell me that they made the decision to not use the gate that morning.”

For a runner, every second, every inch, matters, and Fraser-Pryce didn’t want to expend extra energy to walk the longer distance to another gate while carrying a heavy bag. She waited for at least 30 minutes, allowing the crew manning the entrance to make some calls, thinking eventually she’d be let in. “It wasn’t like there were a hundred people trying to go through the gate,” she says. “Walking to another entrance meant going by pedestrians and other attendees walking.”

During that time, a bus of athletes arrived from the Olympic Village, and she says that more eyes on her made her feel humiliated. With every passing moment, she was making a conscious effort not to get worked up or upset. News outlets would ultimately report on this, and a video surfaced on social media that showed her in a heated discussion with a stadium employee.

She would never be let in, and eventually, she walks to an alternate entrance, and begins her warm-up. There’s a rhythm to her routine, and traditionally, Fraser-Pryce gets to the track three hours before competing so she has time to get into a calm headspace, listen to her gospel music, and then begin her warm-ups. Because of the issue at the gate, she loses an hour.

Things are off, she can feel it. During her final two reps on the track, she can sense her body “shutting down,” as painful muscle cramps wreak havoc in her legs, only rivaling the uneasy feeling in her gut.

Her mind is racing. She couldn’t go out on the track and blow it. She didn’t come this far to plummet like this. Her final Olympics race couldn’t end this way. “I was probably having a panic attack,” she says. “I felt I could see it in front of me—and it was ripped [out of my hands]. I’m a warrior; I’m a fighter. I love rising to the occasion. I wanted to do it for my country, but I had to ask, What's right for me?“

LaQuan Smith top, skirt; Versace sunglasses, ring, shoes

And so, as the public watched an Olympic semi-final with an empty center lane where Fraser-Pryce should have been, she was making her way back to her family, distraught. Upon arriving back to her Airbnb, her son saw her and asked, “Mommy, why didn’t you run?” The warrior dissolved into tears.

In the days, weeks, and months that followed, Fraser-Pryce went nowhere near a track. Instead, the morning after her exit, Fraser-Pryce was on a flight to New York City to spend time off-the-grid with her family near Canarsie, Brooklyn. She did the normal, touristy things: museums, Legoland, going to restaurants.

Being with the people who cared about her the most proved healing. She remembers one night, in the dark before bed, her husband telling her, “‘I know you weren’t sure about 2025, but if that’s something you want to do, you have my support,’” she recalls. “I felt so broken, his support gave me legs.”

There’s a release as Fraser-Pryce shares the story, a loosening of her shoulders, but it wasn’t always this way. She opens her phone and reads me a note she wrote to herself earlier this year about that time: “The last two years have been very difficult. The most painful. I felt abandoned, lost. I couldn't express myself to anyone. I went through so much grief and sadness. But I'm giving God thanks for the ways he showed up for me, nonetheless.”

Gucci jacket, skirt; Richard Mille watch

It wasn’t the first time Fraser-Pryce had been knocked down. She found out she was pregnant right after a devastating toe injury that hindered her performance at the 2016 Olympics, where she won the bronze medal. “When I got pregnant on the heels of that injury, I didn’t get the opportunity to do that [on my timeline]. I was sad,” she says.”

Fraser-Pryce was so worried about what people would think of her pregnancy, she kept it a secret, including from her own mother who learned of the news with the rest of the world. That she was grappling with what having a child would do to her career puts into sharp focus what it means to be a woman in sports and the challenges that come with it. When your body is the vessel for your success, a pregnancy can be seen as a career ender. “For a lot of us here in Jamaica, we are already battling with our insecurities of not feeling like we belong, and not feeling like we are worthy,” Fraser-Pryce says. "But I’ve always had the mentality, I’m just gonna work my way back. That’s how we grew up. That’s how my resilience became so strong. I always thought, Nobody's gonna give me anything. I have to make you see that you need me.”

Still, she didn’t know what getting back to the track would look like post-baby. But in October of 2019, with temperatures hovering around 95 degrees inside of Doha’s Khalifa International Stadium, Fraser-Pryce was prepared to find out. “I faced so much adversity going into that championship; track was the outlet that I had to pour into,” she says. “I believe in the power of alignment. When things are aligned, no one and nothing on this earth can stop that. I was anxious. I was nervous. I was a lot of things. A part of me wanted to prove that I was still good. But being there with my son, I looked at him and thought, it doesn’t matter what happens.”

The race was over almost as soon as it started, and Fraser-Pryce crossed the finish line taking first in 10.71 seconds—in some school zones, that speed’s worthy of a ticket; the equivalent of running almost 21 mph. In doing so, she won her eighth world title, ten years after her first, just a little over two years after giving birth to Zyon (named after the Lauryn Hill song and spelled with a “y” deliberately like “Fraser-Pryce”) in an unplanned cesarean birth.

It’s 6 a.m. on a Tuesday morning, so of course, Fraser-Pryce is at the track, preparing for what she tells me is “her final year, but not a farewell tour.” She’s wearing tan shorts and Nike Pegasus, her 5-foot-one-inch frame a small speck compared to the towering nature of the 35,000-seat Jamaica National Stadium where she stands on the 200-meter line. Her coach, Andre Wellington, is there too, along with two 17-year-old athletes preparing for Jamaica's National Junior Championships that he’s summoned to work alongside Fraser-Pryce. One of her favorite songs, “Black Sheep” by Masicka, is playing out of a small Bluetooth boombox in the background as she warms up. One moment, she’s activating with a resistance band while chatting with Wellington. Next, doing some dynamic stretching.

Once she’s ready to segue into the running drills that mimic what she’ll be doing on the track, like getting her knees up, she changes into a special pair of spikes featuring the birthstones of her grandmother, Zyon, and her own. She was supposed to wear these shoes that August night in Paris for the race she never ran. Now, they’re now the only pair she wears.

Watching Fraser-Pryce push her body to new levels of what’s possible is emotional. The barriers athletes break, in some ways, makes us feel like we’re capable of more, too. And so, as I watch from the sidelines, sitting in the shade, it’s impossible not to find myself rooting for her. Still, I can’t help but wonder: Is the impossible possible this time? As Fraser-Pryce knows as well as anybody, great sports stories aren’t guaranteed to end in greatness.

That, and she’s older now. A decade older than the average age of 27 for track and field Olympians. When I ask her how she feels about competing at this stage of her life, Fraser-Pryce speaks with confidence. “I’m adding to the conversation of what it looks like to be a female sprinter,” she says. “I’m here to inspire someone who may not find success until they’re in their thirties. Now they have a blueprint, because I did it first.”

What’s driving Fraser-Pryce also feels deeper this time around. It’s not accolades or fame she’s chasing; she’s already got that. This lap is for something more important—herself. "This was on my terms. I didn’t tap out because someone said I should,” she says.

Undisputed is that she’ll give it her all. “I’m the kind of athlete that’s always going to come back harder the next time,” she says.

The race, when it comes, will be over in seconds.

And then she’ll slow down, an interesting thought for a woman known for her speed. She’ll focus on her family, her faith, her philanthropy, her hair care company AFIMI—all important parts of who she is. “I want my legacy to be the totality of who I am; the mom, the athlete, the entrepreneur, the philanthropist,” Fraser-Pryce says. “I want it to be about impact. The impact that I've had on and off the track in creating space for other women to understand that they can thrive in life.”

And in that way, she’s already crossed the finish line, smiling with her arms in the air—she’s won.

Photographer: Michael Schwartz | Stylist: Mobolaji Dawodu | Hair Stylists: Ashley Akemi and Autumn Suna | Makeup Artist: Dani Perez | Manicurist: Alexa Estrada | DP: Biagio Musacchia

Special thanks to The Goodtime Hotel

Emily Abbate is a Brooklyn-based, veteran journalist on a mission to empower women to live healthier, happier, and more-motivated lives. Now a 13-time marathoner and triathlete, the certified wellness coach and former fitness editor at SELF is the brains behind the podcast Hurdle, acclaimed by The New York Times as “addictive,” cusping 10 million downloads with listeners in more than 220 countries. You can find her most recent bylines in GQ, Women’s Health, and Marie Claire.