Inside the Lives of White Supremacist Women

And why their numbers are growing.

Shannon Martinez sat on a porch in Marietta, Georgia with her friends. She stared down at her chunky Dr. Martens and picked at her shoelaces as her long chestnut bangs—the only part of her head that wasn't shaved—fell in her face.

An older African-American man walked down the street, as he did every day, passing their house on his way to work.

"Go home!" one of her friends yelled. "Go home, n-----! We don't want you here!"

For a moment, maybe two, the man stared straight at the group—and then he kept walking.

"He didn't look mad. It wasn't even a look of judgment," Martinez says. "It was a look of disappointment, like, I can't believe this is still happening."

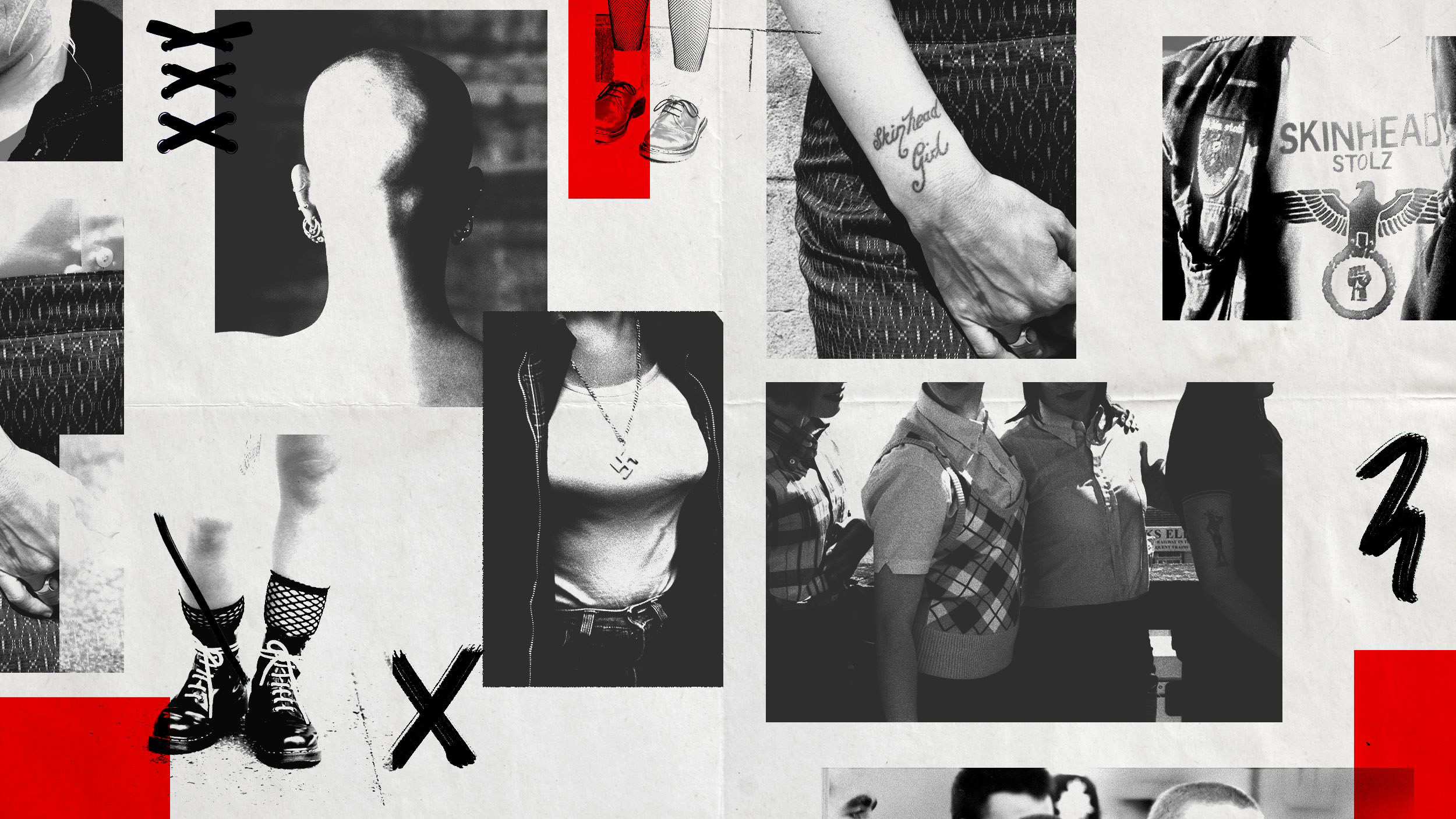

Martinez identified as a white power skinhead for most of her teens. As she bounced around from Michigan to Georgia in the early 1990s, the one constant in her life was her hate group. And she wore the right uniform—red or white laces in her Dr. Martens shoes, a Chelsea haircut (head shaved but for a section in the front), a Fred Perry-brand shirt or sweater under a bomber jacket—so skinheads could find her wherever she moved.

Being a "skin chick" meant one thing to her back then: community.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

But it also meant violence. She and her group didn't stop at spewing slurs and verbal harassment—they threw tear gas into a gay club, used slingshots and BB pellets to attack people's homes, and attended raucous Ku Klux Klan rallies, according to Martinez.

It made them feel, she says, tough and powerful.

White supremacists have gained national attention in the wake of the 2016 presidential election, with former Ku Klux Klan Imperial Wizard David Duke and white nationalist leader Richard Spencer voicing enthusiastic support for President-elect Donald Trump. Despite having himself retweeted messages from apparent white supremacist accounts, Trump eventually disavowed the movement (which had, by this point, celebrated him in the official Knights of the Ku Klux Klan newspaper and held a parade in honor of his presidential victory) and its online contingent, the so-called "alt-right."

But that's done nothing to darken the movement's growing spotlight, or deter the people who are drawn to its beam.

White supremacists may believe the country belongs to white men, but it's an increasing number of white women who are fighting for the cause, says Kathleen Blee, University of Pittsburgh sociology professor and author of Inside Organized Racism: Women in the Hate Movement. The movement appears to be growing overall—the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), which tracks hate groups and their activity, tallied a 48% increase in membership over the last 15 years, and estimates that of the 892 hate groups in the U.S. today, most are dedicated to white supremacy.

"Some have been actively reaching out to women," says Blee, who has interviewed members of the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazi groups, Christian Identity sects, and white power skinhead gangs across the U.S. "They're interested in women because they see them as less likely to attract police attention and less likely to be police informers. Some of the leaders tell me if you recruit women, you get their kids and husbands, too."

White supremacist groups have plagued this country for more than a century. Since the founding of the Ku Klux Klan in 1866, dozens of other destructive organizations have sprouted in its wake, including Neo-Nazis and racist skinheads gangs.

"The groups with Neo-Nazi beliefs tend to be the most violent groups out there now," says Mark Potok, senior fellow at the SPLC. "And the enemies are Jewish people, gay people, Muslims, nonwhites and on down the list."

For Martinez, the attraction to white supremacy was rage. After being raped at age 14 by two men—both white—at a party, she was compelled by what she saw as skinheads' raw and unrelenting anger.

"I believe, in retrospect, that my entrance into the white power movement came as a near-direct result of the self-loathing I felt from that assault," she told MarieClaire.com. "I had hung out with a bunch of punks and scene kids, but the skinheads were the angriest people I knew. I was like, Okay, that's my people."

She says it wasn't really about racism for her, at least not in the beginning. "It was a displacement of my feelings. Like, Me being this way can't be my fault so it must be someone else's fault. The skinheads gave me a place where I could focus the rage and anger I was experiencing," explains Martinez, who grew up in a middle-class household with a mechanical engineer dad and stay-at-home mom. "There was a lack of connectedness in my family growing up, but the skinheads gave me a sense of unconditional belonging."

This is one of the ways new members get their start, according to Blee—they "slide" in from the side, more due to camaraderie than doctrine, and don't fully confront the movement's racist beliefs until they're already bonded with the people in the group.

But somewhere along the way, the hate takes over. And it wreaks havoc. Of the 474 deaths at the hands of domestic extremists between 1996 and 2015, according to the Anti Defamation League, the majority were committed by white supremacists.

"These groups have committed murders, bombings, attacks on gay bookstores," Potok says. "Another big, incredibly dangerous piece of how they commit terror is through propaganda—by spreading lies that legitimize violence against people of other races."

In fact, propaganda about their kids and their safety is one of the ways neo-Nazi gangs like racist skinheads target women. "Things like 'Your kids are going to have to go to school with people who are racist and they're going to learn to hate the white race,'" Blee asserts. "There's a lot of propaganda about nonwhite men being more likely to be rapists—it's not true, but it's part of the propaganda—and it says that, to protect yourself, you need to be involved with the fight for the power of the white race."

There weren't many women in the various skinhead groups Martinez joined—men were the leaders and the very few women played supporting roles. While there are some notable exceptions (one Klan spokesperson is a woman), it's rare for women to have leadership roles or titles in white supremacy groups. It's much more common for women to act as recruiters, luring others into the group.

Jennifer, who asked that her name be changed for fear of retribution, was a racist skinhead in the Midwest during her teens. She didn't commit violence, but helped the cause by passing out leaflets "advocating for racial purity" and making phone calls to senior male members of the group, thanking them for their support and encouraging more involvement.

"My boyfriend was abusive—bad. I always had bruises on my legs," she says of being 14 and dating a 16-year-old skinhead. "It was like, This is how it is. There was no place for women at all. It was like, Stay in bed or in the kitchen."

When she did venture out, Jennifer knew there were risks. Riding in a car with an Asian-American friend one day, a fellow skinhead pulled up alongside them, and Jennifer quickly told her friend to duck down and hide on the floorboard. "My friend was like, 'Why, what's wrong?' and I had to say, 'If they see you with me, they're going to kill me.'"

"It's a very misogynist environment," says Christian Picciolini, the former director of the Illinois chapter of the Northern Hammer Skinheads, who recruited women simply because they would attract more male members. "Even though on the outside, we praised women as being the progenitors of white warriors—they birthed the next generation."

Martinez as a skinhead in her teens

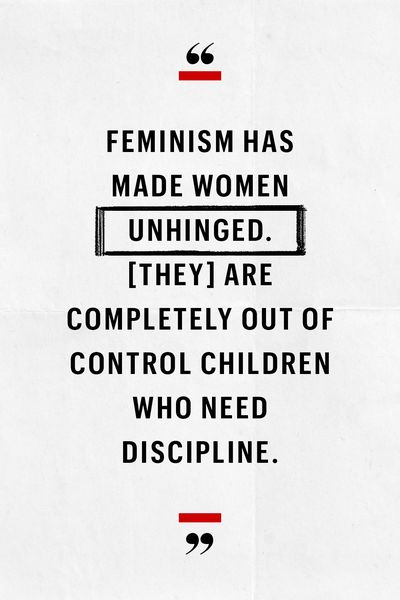

Today, the arguably most vocal faction of white supremacy, the "alt-right," is significantly male-dominated. The neo-Nazi website Daily Stormer, for example, has a recent article decrying women's right to vote, saying: "Feminism has made women unhinged. These people are on a rampage. They have become a collective bloc, intent on forcing their own agenda onto men... Modern women are completely out of control children who need discipline."

But white supremacist women have carved out their own communities online—or so we're led to believe. One site describes itself as "a group of White Nationalist Heathen women writers, artists and film makers. We write about women, parenting, homesteading, self defense, current affairs and philosophy. We aim to return to the ways of our pre Christian ancestors, secure a homeland for the White race and ensure a future for White children." The site, which is peppered with photos of smiling, young white women, includes sections about crafting, motherhood, and yoga nestled alongside sections about "controlled opposition" and "Jews." But Blee says the groups claiming to be for and by women could actually be run by men. "Online, white supremacism is a movement that is based on illusion and subterfuge," she explains. "So it's really important not to take things for what they appear to be. These may or may not really be women."

For Martinez, it was another woman who saved her from the endless cycle of hate groups; after moving to Houston with a skinhead boyfriend, his mother was the one to finally break through. "She took me in and treated me like part of the family," she recalls. "She was able to see through my gruffness. We played baseball and went camping and fishing. I got a job at Kmart. I had not done regular people stuff in so long. It was like, Oh yeah, I remember all of this."

But the thaw took time. "It was several more years of healing before I was able to move on from all of that," Martinez says. Today, the 42-year-old mother of seven works at a local restaurant in Athens, Georgia, home-schools her children, and describes herself as having "radical leftist politics."

"What the hell was I thinking?" Martinez asks now of her troubled—and troubling—past. Jennifer avoided talking about her own for years due to her intense guilt and shame. "I still feel horrible about that day in the car with my friend," she says now. "I can't believe I did that to her." Picciolini even founded a group, Life After Hate, to help people like them cope with what they've done and find a way forward.

Martinez believes it's her obligation to share her story as a cautionary tale—particularly now.

"It's terrifying to me because today I see a lot of parallels with Nazi Germany," she says of the way the white nationalist movement has rallied around Trump, thanks to his campaign promises to build a wall, require a registration for Muslims, and deport millions of immigrants. She finds those policies and their wide support by the movement "completely disturbing."

This year, Jennifer, whose former neo-Nazi gang preached paranoia about and hatred towards Jewish people, took a DNA test and learned she has significant Jewish heritage of her own. "I thought it was fantastic," she says. "And I laughed because I thought of all of those skinhead guys who wanted to sleep with me because I had blonde hair and blue eyes."

Both Martinez and Jennifer are left with permanent scars from their racist skinhead days—Jennifer has a white power cross tattoo on her ankle, which has faded beyond the point of recognition. But the white supremacist version of the Celtic Cross that Martinez got when she was 16, carved by hand with a Bic pen and a nine-volt battery, is still clearly visible on her leg.

"Most people assume it's just a cross or whatever, but if they ask me about it, I tell them what it is," she says. "It's a part of my past, yes, but it's so, so far from who I am today."

Kate Storey is a contributing editor at Marie Claire and writer-at-large at Esquire magazine, where she covers culture and politics. Kate's writing has appeared in ELLE, Harper's BAZAAR, Town & Country, and Cosmopolitan, and her first book comes out in summer 2023.