How the Parkland Students Helped a Columbine Survivor Find Her Voice

For two decades, Salli Garrigan didn't think her story mattered—until Parkland.

Salli Garrigan, a 36-year-old mother of two, was a junior at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, when two shooters entered the school on April 20, 1999 and murdered 12 students and one teacher before turning the guns on themselves. It was the deadliest high school shooting in U.S. history—until the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, on February 14, 2018, that left 17 dead. As the 20th anniversary of the Columbine shooting approaches, Garrigan tells MarieClaire.com, in her own words, what it's been like to watch history repeat itself over the past two decades, and how the Parkland students helped her turn her grief into action.

There are moments that are still so vivid in my mind it feels like yesterday, but then there are some things that feel so long ago. There are little triggers like a song, or even a smell that makes it all come back. We were told this would never happen again. I believed them.

During high school, I was part of the Pom Squad—the school's dance team. I felt most comfortable with the musical choir class and theater kids, though. I was the quirky theater kid—it was where I felt at home. It was my safe haven. I was in my choir room when we started to open our music and we heard a loud bang. That's when pandemonium broke out. I ran towards one set of doors, but then a teacher stopped me and said, "go back in, they're coming up, they're coming up." So I ran the opposite direction to another set of doors, which led to the school's auditorium. I saw other kids rolling in from other parts of the auditorium as well. But then we heard the [author makes rapid gurgling sounds like gunfire] coming from the lower part of the auditorium. We all dropped to our knees. I remember hearing kids screaming, and a screeching fire alarm.

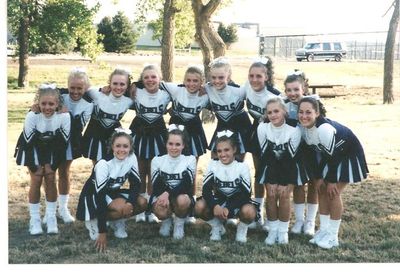

Garrigan (top row, left) with the Columbine High School Pom Squad in 1999.

We stopped and tried to get our bearings. The person in front of me tapped me and told me to keep going. We went across the auditorium to get to the main hall of the school and that's when I saw a friend's little sister who came from the cafeteria. She was white as a ghost. She said there was somebody with a gun. I kept saying, "we'll be okay, we'll be okay, let's just get out of here." So we went towards the front door of the school, and as we turned around a teacher in another hallway quickly pointed us towards a route of safety.

Garrigan’s junior class photo. She wore the same outfit the day of the shooting on April 20, 1999.

We had so much adrenaline. We caught up with a gym class who thought it was just a typical fire alarm, so they were kind of sauntering out. Then suddenly all of us started running and we hurled ourselves over the fence. Now I look back and I'm like, how did we jump over that fence? We made it out to a parking lot in Clement Park—a park right next to Columbine High School. I didn't have a cell phone. I had a friend who did so I asked him, "Is there any way I can call my mom? I feel like I need to let her know I'm not going back to school today." I called her and was like, "I don't know what happened, some people are saying there was a shooting, but I just want you to know I'm okay. They're taking us to the [public library] and that's where I'll be." While we were on the phone she turned on the TV and just said, "Oh my god." And then I was like, "But I'm okay mom, I'll talk to you soon."

The timeline is still a little confusing to me, but I want to say I was out of the school within seven to 10 minutes.

I don't remember mental health resources being offered to us at the time. Our school was very faith-based, so I think a lot of people found help through church. I didn't. I found help through my friends and my family. There were teachers who helped us as well. We all went through it together. We supported each other and were like, "hey, we're here to talk." I can't say the school helped with anything, but then again it was all so new. If anybody cried there would be a camera on you. I felt like we weren't able to heal together because there were always cameras around. We were under a microscope. I don't think anybody really knew what to do. Even the media didn't know how to handle it. Unfortunately, because of that, it glorified the shooters, which caused many copy cats. Look at where we're at now.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

For the longest time doing theater was my outlet. It was my escape. A place to tell somebody else's story. I didn't really hide, but I didn't proactively talk about being at Columbine. I think for a while that actually was helpful. At the time of the shooting, I thought bullying and mental illness was the problem—especially at our school. But as the years went by, I started to realize guns are the problem. I wanted to act and change laws to make it harder for people who shouldn't have guns to get them.

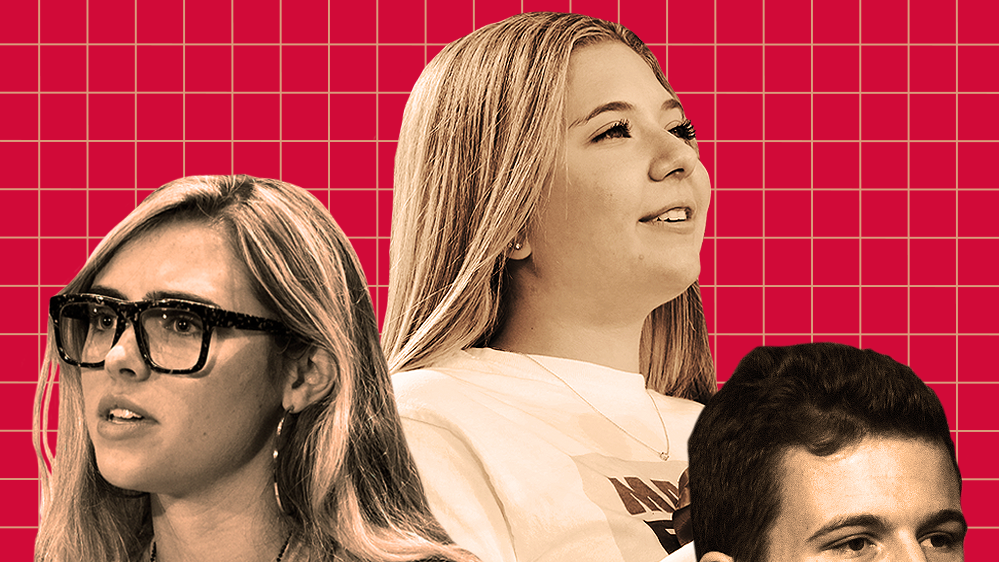

I joined Moms Demand Action in 2016 after the Pulse Nightclub shooting. I was like, if I join maybe I can do something. But I wasn't really active until the Parkland shooting. For the longest time I felt awful. I felt hopeless every time it kept happening again. I would always call my best friend, and we still do unfortunately, just to check in and be like, "how are you doing with this one?" Then we usually have the conversation what do we do? How can we help? I just feel so helpless. I said that for a long time until I saw the Parkland students fighting back and having a voice. I finally realized after all of those years that I, too, could have a voice.

I just want to be that person that says if you don't speak out, 20 years will go by and nothing changes.

I never thought my story mattered or would be enough. But I was encouraged by members of my local Moms Demand Action chapter to share my story at the Parkland vigil last year because of the parallels between Columbine and Parkland. It was rewarding to finally feel like my story could make a difference. I had friends from Columbine reach out to say I had given them the inspiration to share their own stories. It took me 19 years to find a community like Moms Demand Action and the Everytown Survivor Network.

Garrigan picking up her 4-year-old daughter from school in Alexandria, Virginia. "Right now I feel fine dropping her off. When she goes to public school, I'm probably going to have some reservations," Garrigan tells MarieClaire.com. "I'm compartmentalizing everything. I have to go one day at a time or it's going to drive me mad. I'm trying to figure out whether or not a lockdown drill is the right thing to do for kids."

Since the Parkland students started speaking out there's already been so much change. I want more change right away, but they're making incredible, positive change slowly but surely. They're a different generation. They grew up with the lockdown drills. They already knew what was happening again and again and again. It finally happened to them, unfortunately, and they're not backing down. They just keep fighting and they keep it at the forefront of everyone's minds. It's like look at these kids. They're so eloquent when they talk about it. All you want to do is follow whatever they do. For me, I just want to support them and be that person that says if you don't speak out, 20 years will go by and nothing changes.

You have to know that there will be triggers. You have to accept it. That was a thing that was hard for a lot of us at Columbine. We didn't want to let people know we were hurting for the longest time. For me, I wasn't physically injured or in the library, so I felt like oh, I wasn't really a survivor, which is silly. Sometimes you don't think you're really a part of it—even if you were. I know a lot of people who deal with survivor's guilt that plagues them throughout their whole lives. An outlet is so important. The outlet could be doing advocacy work, of course, but you need something else too. You can honor through action, but I highly recommend finding a hobby. For me it was theater. It's so important to find that to make you happy and release those positive endorphins.

Garrigan (right) and fellow members of the Everytown Survivor Network.

I moved out of Columbine in 2007. First to New York, then down to Virginia. It's helped. I highly recommend moving out of the affected community. It can get a little toxic. There are such different beliefs in Columbine. Some people believe in more guns. Some people, like me, believe in gun violence prevention. There's always a little bit of fight about it back and forth, but after 20 years I think people are calmer and coming together no matter what they believe. It's a lot better than it was.

No notoriety is key. We cannot glorify the shooters. That's exactly what they want. It's truly the best day of their lives because they know they'll be a star after it. And when it comes to mental illness, it's about bringing people together. What has helped me a lot is meeting other survivors with unique situations. Connecting survivors to one another, which Everytown does a great job with, along with referrals to direct services, is also important. Know that it's okay to call people.

Even if you feel like you're not a survivor, you can always reach out and text "HONOR" to 64433 to figure out ways to help. People are there to support you. Everyone's narrative matters in this fight.

If you’re thinking about suicide, are worried about a friend or loved one, or would like emotional support, the Lifeline network is available 24/7 across the United States. Call 1-800-273-8255.

RELATED STORIES

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.