It's Time to Stop Treating Black Female Survivors of Sexual Assault as Race Traitors

Supporting Black survivors—not ostracizing us—is a requirement in the fight to combat systemic racism.

Trigger Warning: This piece includes descriptions of sexual assault.

I first met Russell Simmons at a nightclub in New York City when I was a 19-year-old model. Our friendship was cemented in our love of nightlife and consuming alcohol. When I was 21, Russell and I began casually dating, off and on. In the summer of 1994, I called Russell to let him know I was in town and asked if he wanted to hang out, strictly as friends. As we sat in his usual corner booth at Time Cafe, I noticed he wasn’t imbibing alcohol as usual; he said he quit drinking. That didn’t stop me from slamming back glass after glass of Pinot Grigio. As the night progressed, and we went from party to party, I became extremely drunk. I asked Russell to give me a ride back to the apartment where I was staying. Instead, he instructed his driver to take us back to his place. I didn’t think anything of it at the time—I have been intoxicated and alone with male friends in the past and nothing harmful had happened.

I was lying fully dressed on his bed, semi-conscious and slightly immobilized. I felt myself floating off to sleep, but something made me open my eyes. I hazily saw Russell walking towards me, naked and wearing a condom. I told him "no" and tried to push him off me. I did not consent. I tried to stop him. It didn’t matter. My “friend” ended up violently taking something from me that wasn’t his.

In the aftermath, I struggled to reconcile what had happened to me. Without adequate mental health and trauma care, I couldn’t cope. I cancelled bookings and retreated from the modeling world. People in fashion and entertainment rarely have more than two degrees of separation; finding myself in the same room as my perpetrator again was something I wanted to avoid at all costs—which meant giving up my career just as it had started taking off.

It took a long time—years, in fact—before I felt comfortable sharing what happened to me with people beyond my immediate family and closest friends. I wanted to move on and forget about Russell to the extent anyone can when their perpetrator is famous.

In the late 2000s, I became more open about being a survivor. I disclosed my personal experience with sexual assault and immersed myself in the world of activism against gender violence. I made it my life’s mission to push back on a society that doesn’t believe survivors of gender-violence—particularly domestic violence and sexual assault.

We aren’t allowed to acknowledge the suffering of being both Black and a woman in a white supremacist patriarchal society.

It was only when #MeToo gained traction on social media that I began to think I could share my story, along with my perpetrator’s name, and actually be believed. I knew in doing so I was opening myself up to attacks on my character and calls for my public silence—in a way that white survivors don’t experience—because of our race's history of Black men being falsely accused of rape as justification for racial terror and violence, including lynchings.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The specter of false accusations, combined with the Black community's deep-seated mistrust of the criminal justice system, plays a significant role in why Black women who accuse Black men of rape are seen as being complicit in our society's vilification of Black men as violent sexual predators. Our knowledge of how Black men in the United States are pathologized as predatory rapists contributes to the burden Black women feel to protect our men from a broken criminal justice system. The consequence of this legacy is that Black women are placed in the untenable position of having to choose between loyalty to our race or to our gender. We aren’t allowed to acknowledge the suffering of being both Black and a woman in a white supremacist patriarchal society. Those who do speak out about the acts of violence committed against us are viewed as race traitors—something that is regularly pointed out to me on social media.

Despite knowing this, I chose to share what Russell did because I felt that to not do so would be antithetical to everything I have espoused through my advocacy work. For the first time in history, women’s claims of sexual assault and harassment are finally being heard and, for the most part, accepted as legitimate. Around the time that Jenny Lumet became the first woman of color to publicly accuse Simmons of rape in November 2017, I began working with a journalist to also publicly share what he had done to me. I wanted to mitigate any doubt about women who came forward with claims against him by also saying “Me too.”

Nearly eight months after I initially attempted to go public, my story was published in The Hollywood Reporter. Even then, it ended up being dismissed by Russell* and his supporters, who accused me of being a liar. I found myself isolated and rejected by people I had known for decades. After almost a year of fighting to be heard, my voice was suppressed.

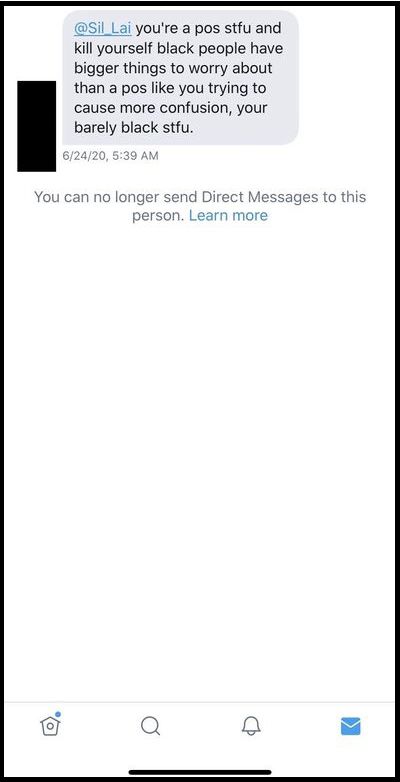

A direct message the author received from a stranger on Twitter.

We’re living in a time when conversations about race are front and center. It is heartbreaking that there are music industry executives, members of the media, and fans alike who still support Russell after so many allegations because he’s a cultural icon and because his victims are overwhelmingly Black.

One of the challenges around the Movement for Black Lives is that the majority of the discourse is centered on cis-heterosexual Black men. This almost singular focus on the police brutality inflicted on Black men created a void that legal scholar Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw's #SayHerName initiative seeks to fill, an effort to direct the public's attention to the extrajudicial murders of Black women and femmes too.

Historically, social movements have pushed the experiences of Black women to the side. We’ve been told to wait. We’re admonished that our cries of suffering—particularly around sexual assault—are a distraction from the movement’s larger goals of addressing police brutality and systemic racism.

I understand why we do this: It is through racial solidarity that we have been able to make social advances in a country that continues to devalue Black lives. But at the same time, dismissing the claims of Black women’s experiences with sexual violence only serves to hold back Black people, as a whole, from liberation and progress.

It is imperative that we elevate the suffering of Black female survivors while simultaneously dismantling the systems of oppression that contribute to the belief that Black women’s issues are a subset of Black issues, while Black men’s issues are, simply, Black issues.

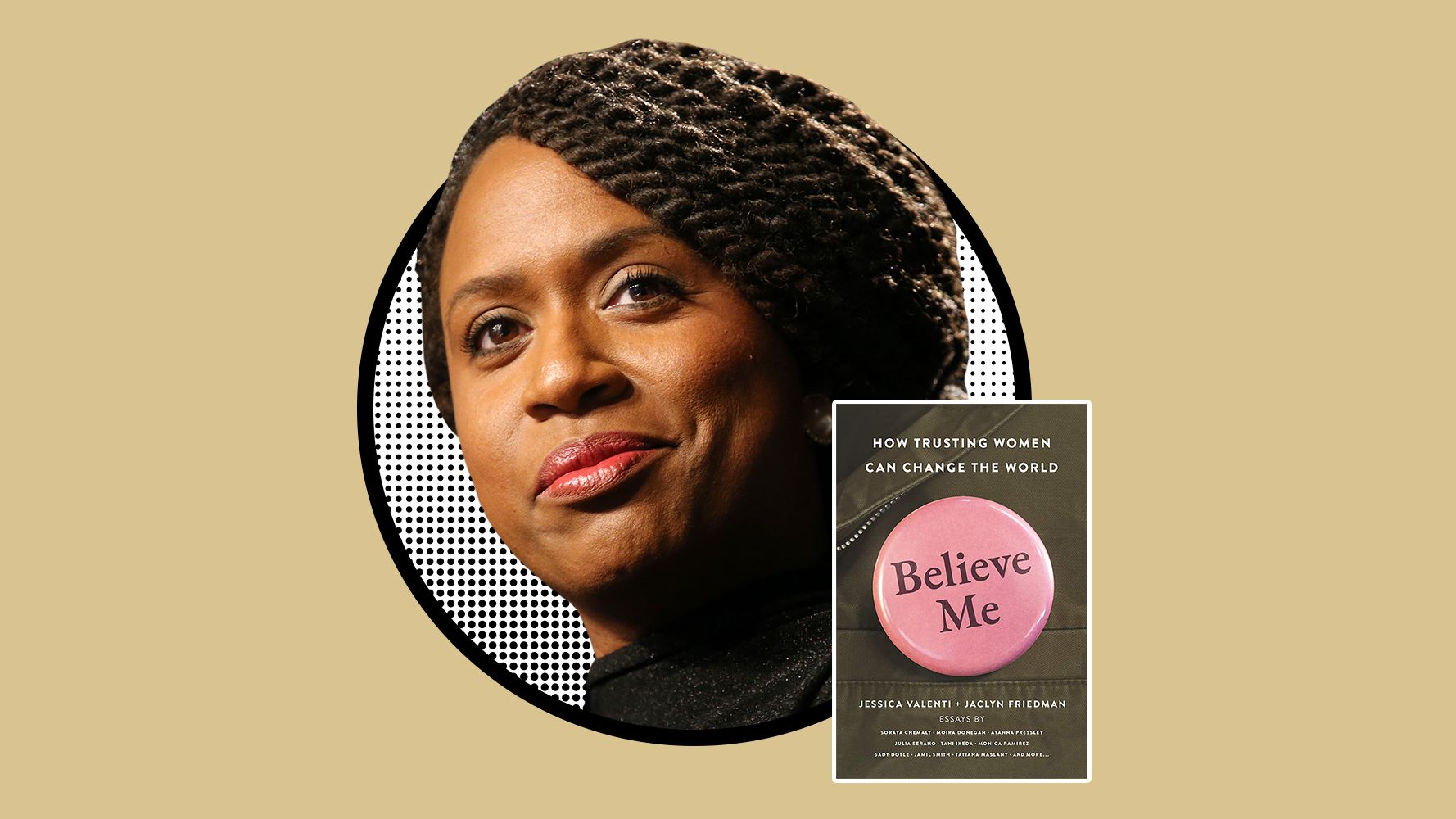

The author at the premiere of the documentary On the Record.

I’m well aware that my privilege as a light-skinned, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied woman with a perpetrator who is famous allows me to share my story in a way many other women cannot—even those who aren’t Black. I’m always thinking about the legion of survivors of sexual violence whose names we will never learn because they are afraid to come forward. They understandably fear not being believed or retribution from the men who assault them or the systems that prioritize men over women, especially transwomen and gender-noncomforming people.

Audre Lorde, a Black lesbian womanist, activist, and poet, famously said, “When we speak we are afraid our words will not be heard or welcomed. But when we are silent, we are still afraid. So it is better to speak.” In speaking out, survivors break societal barriers that police our words and actions. My voice has been heard not just because of my own efforts and that of The Hollywood Reporter, but in large part because of the work of Black female reporters and feminist activists who have fearlessly rallied behind me and other survivors since the documentary On The Record was released. Black women continue to break barriers as we lift each other up in the face of erasure by white media and censure by those in our own community.

But it needs to be a movement that goes beyond the collective efforts of just Black women. The liberation of Black women cannot be secondary to the liberation of our race. By hook or crook, we will hold those accountable who harm or censor us.

This isn’t vengeance. It’s love. Beautiful, radical, transformative Black love.

Sil Lai Abrams is an activist and a primary subject of the HBO documentary On the Record.

*Editor's note: In 2018, Russell Simmons issued a statement to The Hollywood Reporter, via his attorney Patty Glaser, denying all of Abrams' allegations of sexual assault.

RELATED STORIES

Sil Lai Abrams is an award-winning writer and domestic violence awareness activist. She is a sought after speaker on gender violence, race, and depictions of women of color in the media, and has spoken at over three-hundred organizations and universities around the United States. Abrams regularly provides television commentary on gender-violence and has been profiled in numerous magazines, including The Hollywood Reporter, EBONY, Redbook, Modern Woman, and ESSENCE. The Root praised Abrams for her use of “social media to protest the narrative that Black women’s realities can be defined by dysfunctional entertainment” and she has served on the Board of Directors for two of the nation’s largest victim services nonprofit organizations, Safe Horizon and the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Abrams is the founder of Truth In Reality, a media advocacy organization that challenges the racially stereotypical media messaging of Black women and girls. Through digital advocacy, public awareness campaigns, and educational programs, the organization aims to change society’s acceptance of relational violence and reduce gender-based violence in the Black community. In 2017, Abrams was selected as a McBride Scholar at Bryn Mawr College, where she studies sociology and political science. Abrams' books, the 2007 self-help tome No More Drama: Nine Simple Steps to Transforming a Breakdown into a Breakthrough, and 2016 memoir Black Lotus: A Woman's Search for Racial Identity received critical acclaim from numerous literary journals including Kirkus Reviews and the Library Journal. In 2012, her EBONY essay "Passing Strangely" won the National Association of Black Journalists’ “Salute to Excellence Award” in the Commentary/Essay Category as part of the magazine's "Multiracial in America" package.