Oh, Colleen, you're here to butcher the babies again, aren't you?" That's how an antiabortion protester greets Dr. Colleen McNicholas as she maneuvers her silver SUV into the parking lot of the Planned Parenthood clinic in St. Louis' Central West End on an unseasonably warm day in mid-February. McNicholas pulls into a spot—she likes to park in front of the fence nearest the protesters so patients don't have to—and heads to the entrance, carrying two dozen bagels she brought for the clinic's staff.

Once inside, an armed guard waves her through the metal detector and a set of auto-lock doors (the second won't open until the first one shuts). She has just enough time to change into scrubs, shove a few bites of a bagel into her mouth (she'll munch on this one bagel all day in lieu of a lunch break), and wash her hands for the required three minutes before it's time for the first abortion.

By the end of her eight-hour workday, she will have terminated 31 pregnancies.

McNicholas is one of a dwindling group of doctors performing abortions in the Midwest, which, along with the South, is known to pro-choice advocates as the abortion desert. According to the Guttmacher Institute, as of 2011, the most recent year for which data are available, 94 percent of counties in the Midwest had no abortion clinic to serve the 13.2 million women of reproductive age who live there. She works two days every three weeks at the Planned Parenthood in St. Louis—the only remaining abortion clinic in Missouri—flies once a month to the Wichita, Kansas–based clinic where Dr. George Tiller practiced until he was shot dead in 2009 by an antiabortion zealot, and in June will begin traveling to Oklahoma City to work at a newly opened clinic. "Part of the problem with being so committed and feeling so passionate about an issue is that it's hard to say no," McNicholas, 35, says. "It's hard to say, 'I can't do that,' because that means somebody is going without care, and what that means is, they're probably going to have a baby they don't want. So ultimately, I end up saying, 'I can do one more day' or 'I can go one more place.'"

McNicholas leaves her house around 5 a.m. for a flight to Wichita, Kansas.

When she's not crisscrossing the Midwest, she's treating patients at her obstetrics and gynecology practice at St. Louis' Washington University School of Medicine, where she is an attending physician and assistant professor. She also drives two hours to Jefferson City, Missouri, a few times a year to testify before the state Legislature in opposition to bills restricting access to abortions. Once a year, she goes to Washington, D.C., with other doctors to lobby legislators that science ought to trump politics when it comes to providing a procedure that, according to Guttmacher, one-third of all American women will have before age 45. Some nights, she meets with the board members of the abortion-access fund she founded to help Missourian women afford the procedure. (At Planned Parenthood in St. Louis, patients pay from $545 to $1,470, most often out of pocket, as state law prohibits Missouri-based insurance companies from covering the cost, except when the woman's life is at risk.) Whatever precious hours she has left are spent at home with her 5-year-old son (a basketball star in the making) and her partner, an anesthesiologist, who didn't want her name used out of concern for her safety.

It's an exhausting schedule ("Good thing you learn how to not sleep in med school, huh?" McNicholas says, laughing), but one she feels she has to maintain. Soon, however, and to her dismay, her workload may get a whole lot lighter. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court may issue a decision in Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt, the most significant reproductive-rights case to come before the high court in more than two decades—the outcome of which will determine the state of abortion access nationwide for years to come.

McNicholas travels to Wichita once a month to provide care.

At issue is HB2, a law passed by Texas in 2013 that requires abortion clinics to maintain the standards of ambulatory surgical centers, and doctors performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a hospital within a 30-mile radius. Twenty-two states, including Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma, have passed similar surgical-center-requirement laws, while 14 states require abortion providers to have some affiliation with a local hospital. Such legislation is known to advocates for abortion access as Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers, or TRAP laws. In the past five years, states have enacted 288 laws restricting abortion—the most in any five-year period since abortion was legalized in 1973, according to Guttmacher. Since 2011, at least 162 abortion providers of the estimated 553 clinics nationwide have shuttered or stopped offering the procedure, according to Bloomberg Businessweek. Texas saw at least 30 clinics close, and, as a result, women there have had to wait as much as three weeks longer for an appointment and drive an average of four times as far to get to a clinic, according to a survey by the Texas Policy Evaluation Project, a University of Texas–based project to determine the impact of the state's reproductive policies. The survey also found that between 100,000 and 240,000 Texas women between the ages of 18 and 49 have tried to end a pregnancy themselves. "When abortion is illegal, it becomes unsafe and women die—it doesn't go away," McNicholas says. "People think we say that because it sounds scary, but we say it because it is true."

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

When abortion is illegal, it becomes unsafe and women die—it doesn't go away.

In order to determine the legality of the Texas law, the justices will have to revisit a 1992 Supreme Court decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey that said states are permitted to pass measures regulating abortion care so long as such laws do not impose an "undue burden" on a woman's right to terminate a pregnancy. Proponents of TRAP laws say the requirements are necessary to protect women. "Abortion, whether accomplished by an invasive surgery or potent drugs, has significant risks to women," says Anna Paprocki, a staff attorney with Americans United for Life. "Health and safety standards are not a prohibition on abortion ... [they] are common-sense standards that aim to provide maximum patient safety."

Yet the American Medical Association, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Osteopathic Association filed a brief with the Supreme Court in October saying such requirements are "contrary to accepted medical practice and are not based on scientific evidence" and "fail to enhance the quality or safety of abortion-related medical care and, in fact, impede women's access to such care by imposing unjustified and medically unnecessary burdens on abortion providers."

Crosses erected by protesters outside the South Wind Women's Center in Wichita.

All three states where McNicholas performs abortions have admitting-privileges laws on the books. Texas may have put such laws on the map, but Missouri pioneered the legislation, passing the nation's first admitting-privileges law in 1986. Kansas and Oklahoma have also passed privileges laws, but both are currently on hold pending legal challenges. McNicholas has admitting privileges only in St. Louis, which means if HB2 is upheld and Kansas' and Oklahoma's pending laws are enacted as a result, she will no longer be able to perform abortions anywhere outside St. Louis. The clinics in Wichita and Oklahoma City may be left scrambling to find a doctor with privileges, and in the meantime, the women they currently serve— who come from as far away as Texas and Arkansas—will have to drive farther, wait longer, and spend more money in order to get an abortion. "If that happens, it will feel like a whole lot of steps backward," McNicholas says. "I think the word for how I would feel is deflated—disappointed, frustrated, and deflated."

At 7:25 a.m. the next day, McNicholas takes a call from a patient while she brews coffee in the kitchen of her ranch-style home on a tree-lined street on the west side of St. Louis. When McNicholas and her partner moved in about a year ago, they installed an alarm system and security cameras, and met with the local police chief to let him know what McNicholas does. Last September, an antiabortion blogger threatened to protest at McNicholas' home in order to "expose the hidden works of darkness," prompting her to send a letter warning neighbors and asking them to report any suspicious people to the police. And in March, when McNicholas and her partner hosted a Hillary Clinton campaign event at their home with Planned Parenthood president Cecile Richards, protesters picketed on the street out front.

McNicholas was raised on the South Side of Chicago in a family that was "supportive of me being whatever I wanted," she says. In high school, most of her friends were on birth control and some had abortions, and none of them thought of it as an "Oh, my God, crisis," she says. It wasn't until McNicholas went to medical school in rural Kirksville, Missouri, that she realized how different her experience was. "There wasn't anywhere within miles and miles and miles of Kirksville where someone could get an abortion if they needed one," she says. Once McNicholas decided to pursue obstetrics and gynecology (she liked the idea of treating "overall healthy people in a mostly preventive way"), performing abortions wasn't even a question. "As a doctor, my job is not to have an opinion on abortion," she says. "My job is to care for patients."

Coalition for Life St. Louis protesters outside Planned Parenthood in St. Louis.

She didn't get involved with advocacy at first. "I thought doing the procedure was advocacy enough," McNicholas says. But during her family-planning fellowship in 2013, she testified before the Missouri Legislature on a bill restricting access to medical abortions. "It was so eye-opening," she says. "The folks testifying for the bill were all men. I felt like if you're going to make decisions that affect half the population, you should have input from them." But finding other women to testify alongside her was difficult. "When I first started doing advocacy, I would think, Where are all the women who have abortions? Why aren't they standing here with me?" she says. "But as time went on, I was like, Well, we don't expect the people who have colonoscopies to come and talk to the legislature about it." She often ends her testimony with an invitation for legislators to come spend a day with her. "I say, 'Do you want to meet any of these women? Do you want to see what it's like? Do you want to see what kind of impact you're having?'" she says. "Of course, nobody ever does."

If you're going to make decisions that affect half the population, you should have input from them.

Just before 8 a.m., a smattering of protesters stands on the sidewalk near the parking lot entrance. An intern with Coalition for Life St. Louis, who declined to be interviewed, wears a hot-pink vest (Planned Parenthood's unofficial color) and is holding a clipboard next to a sign reading, "Check in here"—a seemingly deliberate attempt to confuse arriving patients. Even though Planned Parenthood warns women about the protesters when they schedule their appointments, many patients stop or pause when greeted by a protester's friendly wave. Others drive in as the intern yells after them, "You have options!" or "Just give us the opportunity to comfort you!" She then scribbles down the car's license plate number and a description of the passengers (she won't say what the information is used for). If any patients stop, the protesters direct them to Thrive St. Louis' mobile unit parked across the street. They tell women they can get a free pregnancy test and ultrasound on the bus, but don't mention that such centers typically counsel women against having an abortion.

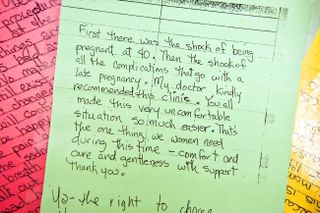

Letters written by former patients in a waiting room at Planned Parenthood in St. Louis.

Once patients are safely in the parking lot, they're greeted by a volunteer from the advocacy group NARAL Pro-Choice America, who escorts them inside. There are 22 abortions on the schedule today. The majority of patients in McNicholas' care fit the profile of women seeking abortions in the U.S. Nationally, more than half (58 percent) are in their 20s, 61 percent already have one or more children, and nearly 70 percent are economically disadvantaged.

Of the patients McNicholas will see today, one is a 24-year-old mother of three from St. Louis whose IUD—the most effective form of contraception available—failed. "This is a situation I tried to prevent," she says, adding that she just started nursing school. She's fired up about her right to make her own decisions about having more children. "I mean, how would you feel if someone came to you, telling you, 'You shouldn't do this because I believe in God'?" she asks. "That's like saying, 'I'm a vegetarian, so you can't eat meat.'" Another patient is a 24-year-old who drove from a small town about three hours away. She says she was drugged and raped at her own housewarming party. "I never in my mind thought I would be here—this is a nightmare," she says. "But this is a decision I had to make because, yeah, I could do adoption, but when that kid hunts me down one day, they're going to say, 'Why?' And I'd have to say, 'Well, you're a product of rape.' That's nothing to put on a kid."

Whether McNicholas is performing a medical abortion, where the patient takes one pill at the clinic and a single dose of four others within the next 48 hours at home, or a surgical abortion, where the pregnancy is suctioned out of the uterus, she only needs about 10 minutes with each patient. She enters the room with a big smile and a cheerful hello, immediately trying to put patients at ease. The first question from surgical patients is usually, "Will it hurt?" McNicholas tells them she can't promise it will be painless—most patients experience varying levels of cramping—but she can say it will be over quickly. The actual procedure only lasts three to five minutes. "You can handle anything for three minutes," she tells patients.

The 40-person staff at the Planned Parenthood in St. Louis constantly worry that the state Legislature will find a way to shut them down. "Anytime there's some new restriction, we have to step back and say, 'What is our current work flow, and how does that need to change? What's our current paperwork, and how does that have to change? What's our current training, and how does that have to change?'" says Mary Kogut, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region and Southwest Missouri. The clinic's medical director, David Eisenberg, adds, "We have spent so much time, energy, and money defending ourselves against these attacks. If they can't stop us from taking care of women, they're hoping they can bleed us dry in the process."

Feeling like they have a target on their backs is not without cause. The state Legislature is currently trying to pass a measure to defund Planned Parenthood, pulling nearly $380,000 in financial support. Legislators successfully stopped the state's only other abortion provider—a Planned Parenthood clinic in Columbia, home to the University of Missouri—from performing abortions last winter. The Columbia clinic had been unable to provide abortions since 2012, when its doctor left for a military deployment. In 2014, when Laura McQuade took over as president and CEO of Planned Parenthood of Kansas and mid-Missouri, one of her primary goals was to get abortion care up and running again. She started looking for a doctor and eventually connected with McNicholas. After a lengthy licensing, inspection, and credentialing process, the clinic was approved to start providing abortions on July 14, 2015. "Within one week," McQuade says, "our schedule was full."

Teenage boys from a local Catholic school protest outside Planned Parenthood in St. Louis.

The very same day, however, the Center for Medical Progress (CMP), an antiabortion organization, began releasing undercover videos purporting to show Planned Parenthood officials discussing donating fetal tissue from abortions to research. CMP used the heavily edited videos to make the case that Planned Parenthood was illegally selling fetal tissue for profit, which Planned Parenthood denies. (CMP's director, David Daleiden, has since been indicted on a felony charge of tampering with a governmental record and on a misdemeanor charge related to intent to purchase human organs, and faces up to 20 years in prison; he has petitioned the court to have the charges dismissed. Twelve state investigations have cleared Planned Parenthood of any wrongdoing.)

Within days, Missouri's Senate formed an ad hoc committee, called Sanctity of Life, to investigate the state's Planned Parenthood clinics, though neither participates in a fetal-tissue-donation program. The committee applied pressure on the University of Missouri, where McNicholas had obtained admitting privileges, and in December, the college revoked the category of privileges McNicholas had been granted, making it so the Columbia clinic could no longer provide abortion care. "I'm horrified that Missouri has gone back to being a one-provider state," McQuade says. "We remain deeply frustrated that we are unable to provide women the health care that they deserve and that we have the ability to provide, but [we] are being blocked by a hostile legislature."

The result is few doctors with privileges—often none in the same town or city as a clinic—so doctors like McNicholas rack up frequent-flier miles, jetting from state to state to provide care.

They aren't alone: Admitting privileges are often incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to secure. Many hospitals refuse to grant privileges on religious grounds (nearly one out of nine hospital beds in the country is in a Catholic-run facility), or because they receive a large portion of their funding from a state legislature (as is the case for state- and university-run hospitals) and don't want to risk losing their financial support by becoming embroiled in the politics of abortion. Other hospitals may have requirements that all physicians with privileges admit a certain number of patients a year, which is an impossible quota for abortion providers to meet because the procedures are extremely safe (Guttmacher estimates that the risk of major complications requiring hospitalization is less than 0.05 percent). The result is few doctors with privileges—often none in the same town or city as a clinic—so doctors like McNicholas rack up frequent-flier miles, jetting from state to state to provide care.

On Friday, McNicholas' alarm rings at 4 a.m. She's on one of the first flights of the day to Wichita, where she will spend the next two days at the South Wind Women's Center, one of three clinics in Kansas. It's run by the Trust Women Foundation, which opens abortion clinics in underserved communities (its second is slated to open in June in Oklahoma City; McNicholas will fly in to work there once a month). Named in honor of Dr. George Tiller, who often wore a button reading, "Trust Women," the foundation reopened the clinic in the same facility four years after Tiller was assassinated in 2009 in his church by antiabortion extremist Scott Roeder. (Roeder was convicted of murder and is serving a life sentence.)

Founder and CEO Julie Burkhart heads both the foundation and the clinic. She worked for Tiller for seven years and has six photos of him framed in her office. Burkhart says she "felt a calling" to reopen the clinic after his death. When she approached McNicholas to work at the facility, McNicholas carefully considered the decision. "I certainly don't make light of security," she says. "But one of the things that drove me was that I felt it was a really important stance from the abortion community to say, 'You're not scaring us—we're not going to stop doing what we're doing just because you walked into somebody's place of worship and murdered them.'"

McNicholas puts a patient at ease.

Today, like most days, protesters have set up a dozen small wooden crosses and a handful of gruesomely graphic signs outside the center's entrance. One protester screams, "Children do not deserve the death penalty—they don't want to be torn limb from limb! Repent before the hand of God comes against you!" as patients make their way inside. The woman has also knitted a baby blanket to show to arriving patients. "It helps women realize it is a baby and if they let it live, they will enjoy it," she says.

McNicholas is ushered inside by an armed security guard who worked as Tiller's personal bodyguard for 17 years. (He wasn't with Tiller that day in the church; "He felt pretty safe there," says the security guard, who didn't want to be identified.) Within 10 minutes, she's inside an exam room with the first patient. She will perform 24 abortions today and 17 tomorrow before heading home. "Lots of people assume the hardest part of my job is the work—abortion after abortion, how sad that is," she says. "But the truth is, the hardest part of my job is when I have to say no to somebody." Most often, McNicholas says, she has to say no not for a medical concern, but a legal restriction—increasing numbers of women are getting abortions later because it takes time for them to scrape together enough money to drive hours away, stay in a hotel, and afford the procedure. By the time they arrive, they've passed the legal limit on the number of weeks pregnant they can be and still have an abortion. (In Kansas, the law permits abortions at or after 20 weeks if the woman's life is endangered.) "It's so devastating to me to see a woman's face when they don't want to be pregnant and you're the last person who can help them, and you can't," she says. "They are forced to continue with their pregnancy by law."

It's so devastating to me to see a woman's face when they don't want to be pregnant and you're the last person who can help them, and you can't.

With the Supreme Court decision looming, McNicholas can't help but think of the many more women she may have to say no to in the coming months as a result. "I don't know what is going to happen, or what changes or requirements we will have to take on," she says. "But those of us who provide abortion care are an innovative, creative, and determined bunch—we will continue to find ways to make sure women have access." For now, she remains focused on her current patients. "The best part is when somebody gets off the table and gives me a hug because they feel like, I just got my life back. I'm going to walk out of here and have a new start—whatever my goals are, I'm going to reach them," she says. One of her hopes for telling her story, she says, is that other doctors will say, "If she can perform abortions in three places, then I can do it in one."

"It does feel overwhelming and daunting to take this on," McNicholas admits. "But it's doable—you really just need that first hug from a patient and then you're hooked."

Back in Wichita, she completes the last abortion of the day just before 3 p.m. She checks on her patients in the recovery room, and then she's out the door, with 30 minutes until her flight takes off. She makes it through airport security just in time to board the plane. She'll have one day at home with her family tomorrow before it all begins again.

This article appears in the June issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now. (An earlier version of this article inaccurately stated that the results of the survey of Texas women were those who have tried to end their pregnancy after HB2 was enacted, when in fact the study did not focus on post-HB2 attempts. The error has been fixed.)

-

Olivia Rodrigo Finds the Perfect Spring Dresses at Reformation

Olivia Rodrigo Finds the Perfect Spring Dresses at ReformationShe's worn the brand twice in the past week.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Curiously, Just as Meghan Markle Sends Samples of Her New Strawberry Jam Out, the Buckingham Palace Shop Starts Promoting Its Own Strawberry Jam on Social Media

Curiously, Just as Meghan Markle Sends Samples of Her New Strawberry Jam Out, the Buckingham Palace Shop Starts Promoting Its Own Strawberry Jam on Social MediaThe clip promoting the Buckingham Palace Shop’s product—we cannot make this up—is set to Mozart’s “Dissonance Quartet.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Zendaya's Latest 'Challengers' Serve Is Nearly a Century Old

Zendaya's Latest 'Challengers' Serve Is Nearly a Century OldThe 1930s-era dress may have been pulled months ago.

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

Documentaries About Black History to Educate Yourself With

Documentaries About Black History to Educate Yourself WithTake your allyship a step further.

By Bianca Rodriguez Published

-

In 'We Are Not Like Them' Art Imitates Life—and (Hopefully) Vice Versa

In 'We Are Not Like Them' Art Imitates Life—and (Hopefully) Vice VersaRead an excerpt from the thought-provoking new book. Then, keep scrolling to discover how the authors, Jo Piazza and Christine Pride, navigated their own relationship while building a believable world for Riley and Jen—best friends, one Black, one white, dealing with the killing of an unarmed Black boy by a white police officer.

By Danielle McNally Published

-

Love Has Lost

Love Has LostQuasi-religious group Love Has Won claimed to offer wellness advice and self-care products, but what was actually being dished out by their late leader Amy Carlson Stroud—self-professed “Mother God”—was much darker. How our current conspiritualist culture is to blame.

By Virginia Pelley Published

-

What Does "ROC" Mean at the Tokyo Olympics?

What Does "ROC" Mean at the Tokyo Olympics?It's a temporary workaround in the aftermath of Russia's massive doping scandal.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Trolls Thought I Was Anthony Weiner’s Cyber Mistress

Trolls Thought I Was Anthony Weiner’s Cyber MistressTen years later, I realize I shouldn’t have been ashamed.

By Megan Broussard Published

-

Celebrate AAPI Heritage Month With Gold House's 2021 A100 List

Celebrate AAPI Heritage Month With Gold House's 2021 A100 ListVice President Kamala Harris, Oscar-winner Chloé Zhao, Naomi Osaka, and Saweetie are just a few of the leaders uplifting the AAPI community this year. Here's how to show your support.

By Ying Chu Published

-

The Unbearable Whiteness of Ballet

The Unbearable Whiteness of BalletIn an exclusive excerpt from her new book Turning Pointe, contributing editor Chloe Angyal lays out the ways that white supremacy is embedded in ballet's most basic foundations.

By Chloe Angyal Published

-

Magi Was Excited to Be the First Ethiopian on 'The Bachelor.' Then Came the Tigray Conflict

Magi Was Excited to Be the First Ethiopian on 'The Bachelor.' Then Came the Tigray ConflictHer fellow contestants rallied around her during ethnic cleansing in her Ethiopian home.

By Emily H. Johnson Published