Donald Trump Is Inspiring More Women to Run for Office Than Ever Before

Why women all over the country are newly motivated to get off the sidelines, roll up their sleeves, and enter the world of politics.

Alex Lipman's political career started over a cocktail, a plate of gnocchi, and a sensation of cold fear at the prospect of a Donald Trump presidency. Coming down from the stress of exams, Lipman, a 30-year-old law student at DePaul University, was out to dinner with friends in late May when the conversation turned to the contentious presidential election. Trump was the presumptive Republican nominee, and stories of his unorthodox views and offensive behavior—his proposals to ban Muslim immigration and to build a wall along the southern border, his comments denigrating women and suggesting Mexicans are rapists—had Lipman's dinner companions in a state of panic and dismay. "There was this overwhelming fear that rights across the board were about to be destroyed," Lipman recalls.

Before that dinner, politics interested Lipman but weren't an animating force in her life. "These policy conversations, conversations about representation, didn't really exist in my world before this cycle," she says. "I'm about to graduate, and I was trying to figure out what I was doing with my life." She's still planning to practice law at a firm, but when she took note of her peer group's anxiety about the election and their fresh interest in politics—as well as her own—she started crafting an addendum to her plan: She would run for a position as an alderwoman, the equivalent of a city council member, in her hometown of Chicago. Trump's victory in November solidified her decision.

It's an uphill battle: While Lipman is left-leaning, she will run as an independent in a city dominated by hierarchical Democratic politics. But she believes the unpredictable results of this last election demonstrate that she, too, can overcome the obstacles of funding, party backing, and playing by the political rules. "If I have the willpower and a decent enough message that constituents believe in and agree with, it doesn't matter if I have the money or the connections or if I'm fighting the Democratic machine here in Chicago," she says. Watching Hillary Clinton's near win and Bernie Sanders' insurgent campaign also gave her hope that both women and grassroots efforts can succeed. Trump made her angry, but fury is not what drove her to run. "It wasn't outrage," she says. "It was empowerment."

Trump made her angry, but fury is not what drove her to run. "It wasn't outrage," she says. "It was empowerment.

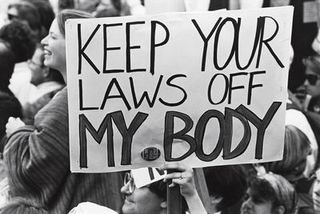

Lipman is one of a critical mass of women across the U.S. shocked into action by the 2016 presidential election—and, as a result, some are angling to get their names on a ballot in the coming years. Women are standing up in other ways, too: Building on a rich history of women taking to the streets to call for everything from the vote in the 1910s to equal rights in the '60s and reproductive rights in the '80s, in January, millions of women participated in the Women's March on Washington in D.C. and in cities all over the country and around the world to stand up for their rights. Organizations from Planned Parenthood to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) are seeing influxes of donations—Planned Parenthood received some 80,000 donations in the days after the election, and at the ACLU, whose website crashed on November 9 from so much interest, donations were up 7,000 percent within a week of the election. But, according to groups that train and promote female candidates, what's unprecedented is the number of women throwing their hats into the political ring.

"On November 8 and in the wee hours of the morning of November 9, like 4 a.m., my phone was buzzing off the nightstand," says Diane Fink, executive director of Emerge Maryland, a Frederick County, Maryland–based organization that helps Democratic women run for office. "It was women saying, 'I want to do something.'" Emerge saw applications to its candidate training program double. "That was a shock," Fink says. "We expanded our class because of it." (Emerge typically caps its candidate training class at 15; this year, it went up to 23.)

At She Should Run, a nonpartisan organization in Washington, D.C., that also assists women considering entering politics, the response has been similarly overwhelming. "What we heard from women throughout the cycle is how disgusted they were about the discourse that was taking place around politics, and especially the misogyny we were seeing front and center," says Erin Loos Cutraro, the group's cofounder and CEO. "Since Election Day, we've seen over 4,500—and counting—women step up. To give you context, we usually see about 100 or so women come into She Should Run each month. It's quite remarkable."

On November 9, Lipman and millions of American women like her woke up to a new normal: a country where the president-elect is a man who has bragged about groping women, calls women who challenge him pigs and dogs, sexualizes and sometimes humiliates women he finds attractive, and who ran a campaign many found shockingly misogynistic. The difference between the percentage of men who voted for Trump and women who voted for Clinton was 24 points, the biggest gender gap in 44 years. And women of color rejected him especially forcefully: Just 8 percent of African-American women and 26 percent of Latina voters cast ballots for Trump. "There has been an awakening after this election, an awakening that we are now all living in a Donald Trump country," says Stephanie Schriock, president of Emily's List, which endorses and raises money to support pro-choice Democratic women. "And these women, particularly young women, realize they are the ones who are going to have to stop this. And they are rolling up their sleeves and saying, 'Put me to work.'" But no matter your party choice, "We need women involved and running—this needs to be about more than supporting or not supporting the president," says Lauren Leader Chivée, CEO and cofounder of All In Together, a nonpartisan women's organization that works to advance female leadership. "All In Together has always been committed to helping women of both parties do that, but it does feel like the response lately is, 'I get it now; tell me what to do and I'll do it.'"

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Monica Weeks has her sleeves rolled up. "After the election, I was like, I have to do something. I can't not," says Weeks, a 29-year-old Cuban-American. "And it can't just be volunteering. It needs to be a real action." She and her husband have started talking about moving from their current home in Washington, D.C., back to Weeks' home state of Florida, where she feels more connected to the Cuban-American community and thinks she could make a bigger impact. That's their first priority for 2017: Make a plan, including sketching out a timeline, for Weeks' run for a local position in Miami. "It's really daunting to think about," Weeks says. "But for me, I see this as part of my civic duty. My way of giving back to society is helping with women's rights."

Weeks works as a photographer and an interior designer, and while she has long supported women's rights, electoral politics have held much less appeal—some of her views don't fit into neat ideological boxes, and she values authenticity and the ability to speak her mind freely. "I thought I'd be more powerful and have my voice heard more outside of Congress, because I always thought I would have to compromise my values in order to be in politics," she says. "I love House of Cards, but it's like, Oh, my God, do I have to be this terrible of a person to do well in politics?"

This election changed that equation. She watched women like Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren and Nevada Democrat Lucy Flores, who lost her congressional bid, fight for what they cared about without selling out. "There are more badass women coming out and giving me more hope," Weeks says. She admires Clinton as well, she says, "but a lot of what inspired me to do this was fear and, frankly, anger."

She also thinks she's uniquely positioned to convince skeptical voters to support her and the policies for which she would advocate, including reproductive rights, education, and preserving the Affordable Care Act. "A lot of my family voted for Trump," Weeks says. "And I think what I bring is an empathy and an understanding of what 'those people' feel, but I'm also able to talk to them and say, 'This is why I think these policies are better for our community.'"

The forces driving many of the women who run are exactly what Weeks describes: a combination of anger at the election results, passion for the issues they care about most, and a deep dedication to the next generation. "A theme coming from women who are stepping up for the first time is outrage, not just at the direction this country is going, but also at the overall rhetoric and environment that we have created for women and for girls," says She Should Run's Loos Cutraro. "We have a lot of women with daughters or girls in their lives who want and expect their voices to be heard, and want to be a role model."

When she was still toying with the idea of running for alderwoman, a turning point for Lipman was watching an anti-Trump ad that showed women and girls looking in the mirror as clips of Trump play in the background. "I'd look her right in that fat ugly face of hers," he declares in one of them; in others, he says, "She ate like a pig," and evaluates women based on their breast size. Lipman choked up watching that ad, and even describing it months later and imagining what it must feel like for little girls to hear their president speak so contemptuously about women, her voice wavers. "It's not, 'Wow, you're a douche bag,'" she says. "It's, 'Wow, you are the face of the entire United States.'" Wherever she can, Lipman wants to counter that message and change the narrative.

According to Emerge Maryland's Fink, this is very much a female thing. "Women run because of a desire to make change, and something they see needs to be fixed," she says. "Men tend to run because of power."

Women run because of a desire to make change, and something they see needs to be fixed. Men tend to run because of power.

Wanting to fix what's broken is Marion Johnson's story. The 29-year-old grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina, and now lives in Durham, where she works at the North Carolina Justice Center. "The issue that really got me 'radicalized' was the Black Lives Matter movement and police brutality," Johnson says. Trump's entire candidacy revolted her, but as a young African-American woman, she also didn't see Clinton as a candidate reflective of the full scope of her concerns. "In some ways, I did feel inspired by Clinton, and in other ways, I don't relate to her," Johnson says. "She is a woman and we went to the same undergrad [Wellesley], so there's that connection, but she's older, she's white, she's rich—so I felt like in so many ways I'm voting for someone who doesn't know what it's like to be me. And then I realized that the only person who understands that is me, and so I should run for office."

Johnson is now considering running for city council or another local position where she can influence the policies that directly affect her neighbors—things like affordable housing and police accountability. In conversations with colleagues and friends, she's heard from other women who are thinking about running, too. "We're realizing that it's important to have somebody who understands our lives as women representing us," Johnson says. "And the best person for that job would be ourselves."

It's not just liberal women making this calculus. Aly Higgins, a 26-year-old Washington, D.C., resident originally from New Hampshire, says she had long toyed with the idea of running for office, but this past election was a turning point. "People are realizing that if they want to make a change, they have to step up and start seeking it," Higgins, a registered Republican, says. She adds that Trump's win was emboldening in the sense that "it showed you that anyone can do this." On election night, she waited for the results to come in at an event with Elise Stefanik, a 32-year-old Republican congresswoman from New York; watching a fellow Millennial woman who represents the issues Higgins also cares about—a strong national defense, a balanced budget, states' rights—pushed Higgins to really consider following in Stefanik's footsteps. "This year on both sides, there weren't enough women who ran, and Congress is not representative of our population," Higgins says. She's working with She Should Run and the Republican PAC RightNOW Women to figure out next steps. "It is so important that we have more women at the table."

This year on both sides, there weren't enough women who ran, and Congress is not representative of our population.

The question political parties and women's organizations are now asking is how to sustain this energy. It's not just that many more women want to evolve into successful politicians; women who have no interest in running for office themselves are also giving money and volunteering to help put other women in positions of power, creating a wave of political sisterhood that could influence elections for years to come. "We've seen an incredible uptick in women and men, but mostly women, donating," says Schriock, of Emily's List. "Over 60 percent were first-time donors."

According to Bob Bland, one of the organizers of the Women's March on Washington, "One of the reasons why I got into [organizing the march] in the first place was to help to make leadership more representative in this country. With equity in leadership, we will experience equity in society." Getting women out marching was just the first step; organizers are now trying to funnel women into the political pipeline, or at the very least keep them politically engaged in an environment where many women find politics offensive and taxing.

Both the Democratic and Republican Parties say they want to cultivate a new generation of leaders. But young women interested in political careers, or even involvement, are at a greater disadvantage. They're saddled with all of the usual reasons women don't run for office—a lack of confidence in their own skills and their ability to raise money, fear that their private lives will be put under a microscope or that they will be scrutinized for their looks, as well as an absence of institutional support and political connections—plus the reality that women under 35 are in the busy stages of building their lives. Focusing on their careers, getting married, and raising children doesn't leave much time, let alone money, for campaigning.

For Amanda Litman, a 27-year-old self-described "campaign hack" in New York (she was the Clinton campaign's e-mail director), the Democratic Party's sluggishness in investing in young people after the election has been particularly infuriating, especially given the current vacuum in Democratic leadership. Despite the fact that Millennial voters trend left, many of the most prominent progressive figures—Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton—are all grandparents over age 65. "Right after Election Day, there was a lot of conversation about the future of the Democrats," she says. "Part of that conversation included building the next generation of talent"—but it didn't go anywhere, and party higher-ups quickly moved on to other matters. "I started thinking, The party is in shambles, there's no leadership, they're rebuilding infrastructure, and there is no outside group that exists to support people under the age of 35 to run for office." So she decided to start one.

The first problem to address, Litman says, is that the way the party recruits is backward: "They focus on the seat first and ask, 'Who do we know we could get to run?' And that limits them to the people they know, who tend to be old white dudes." Campaigns are expensive and often turn into full-time jobs, which is why so many candidates are older and retired, or lawyers whose firms will keep them on the payroll.

To counter that, Litman's group, which is still in the process of starting up, would meet young people where they're at, through ads on Facebook and social media, and cultivate political talent where it resides, then channel those candidates into competitive races. It would fundraise and financially support young candidates. And it would offer a fellowship program providing contenders with a monthly stipend to cover expenses while they're out of work, on the campaign trail. When she tweeted about her idea, she says she received "an avalanche of responses." It's not that young people aren't interested in the electoral process; it's that people at the top of the organized party structures have too often seen Millennials as a voting block, not as potential leaders.

But as much as she believes a Trump presidency will be a catastrophe, his unlikely rise rewrote the political playbook. "The usual path to politics has been blown to smithereens," Litman says. "This is a chance for young women and young people broadly to do their own thing. It's terrifying, but also freeing."

Alex Lipman, who is planning her run for alderwoman in Chicago, is already taking advantage of this new political landscape. She has a website, is learning about how to fundraise, and is honing her campaign pitch. The election isn't until 2019—"But," she says, "I'm ready to go."

This article appears in the March issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now.

Jill Filipovic is a contributing writer for cosmopolitan.com. She is the author of OK Boomer, Let's Talk: How My Generation Got Left Behind and The H-Spot: The Feminist Pursuit of Happiness. A weekly CNN columnist and a contributing writer for the New York Times, she is also a lawyer.

-

Jennifer Lopez Matches Her Greige Sweater to Her $80k Birkin

Jennifer Lopez Matches Her Greige Sweater to Her $80k BirkinThat's some CEO-level color coordination.

By Kelsey Stiegman Published

-

Amelia Gray Borrows Anne Hathaway's Red Versace Corset Dress

Amelia Gray Borrows Anne Hathaway's Red Versace Corset DressIt's the sisterhood of the traveling mini.

By Hanna Lustig Published

-

Prince Andrew's Infamous 'Newsnight' Interview is Revisited in Amazon Prime's New Miniseries 'A Very Royal Scandal'

Prince Andrew's Infamous 'Newsnight' Interview is Revisited in Amazon Prime's New Miniseries 'A Very Royal Scandal'The streamer released all three episodes on Sept. 19.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

11 Books That Are the Antidote to Toxic Girlboss Hustle Culture

11 Books That Are the Antidote to Toxic Girlboss Hustle CultureThese memoirs and nonfiction titles will inspire you to focus on your personal ambitions.

By Andrea Park Published

-

Almost Famous

Almost FamousHalf of the Shondaland dream team, the woman whose work brings 'Bridgerton' to life, is one of the most influential producers in Hollywood. And she’s ready for everyone to know it.

By Jessica M. Goldstein Published

-

Payal Kadakia Is Finally Sharing Her Secret Sauce to Success

Payal Kadakia Is Finally Sharing Her Secret Sauce to SuccessIn her new book, LifePass, the ClassPass founder gives you the tools to write your own success story.

By Neha Prakash Published

-

The Power Issue

The Power IssueOur November issue is all about power—having it, embracing it, and dressing for it.

By Marie Claire Editors Published

-

J. Smith-Cameron Is in Control

J. Smith-Cameron Is in ControlShe’s Logan Roy’s right hand. She’s Roman’s ‘mommy girlfriend.’ And she’s a fan favorite. Here, the Succession star takes us behind the scenes of Gerri’s boardroom power plays.

By Jessica M. Goldstein Published

-

What Makes an Olympic Moment?

What Makes an Olympic Moment?In the past it meant overcoming struggle...and winning. But why must athletes suffer to be inspiring?

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

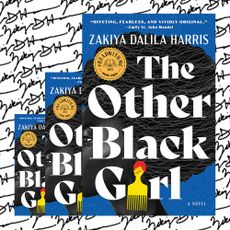

'The Other Black Girl' Gets Real About Racism in the Workplace

'The Other Black Girl' Gets Real About Racism in the Workplace"It really hits home how many spaces don’t allow Black women to really show up as their authentic selves."

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

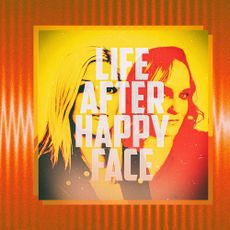

Melissa Moore's 'Life After Happy Face' Podcast Looks at Killers Through New Eyes

Melissa Moore's 'Life After Happy Face' Podcast Looks at Killers Through New EyesThe true crime expert and daughter of the Happy Face Killer opens up to Marie Claire about destigmatizing the label of 'criminal's kid.'

By Maria Ricapito Published