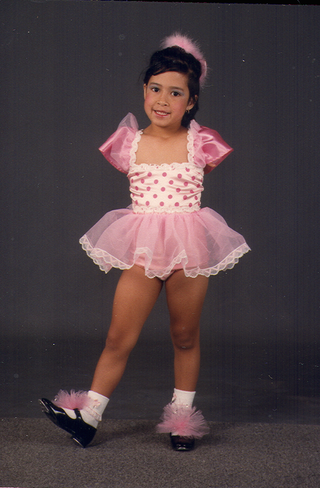

The first thing you'll notice about Jessica Cox, 32, is that she has no arms. It's okay—she's used to the stares. But when you actually talk to the first—as in, like, ever—armless pilot and black belt, you learn that her arms don't define who she is.

Cox has lived with her condition since birth with no explanation as to why she was born without what most of us view as essential appendages. But c'est la vie because this is all Cox has known her entire life, and she's adapted quite nicely to her surroundings—she can fly planes for goodness sake. And when she's not attacking a punching bag with her heels or finishing her documentary Right Footed, Cox makes her living as a motivational speaker. After you hear her backstory, you'll understand why everyone finds her so inspiring–we guarantee it.

Marie Claire: You're not an amputee—in your case, you were born without arms with no known medical explanation. Was it frustrating to have no understanding of your body when you were younger?

Jessica Cox: It bothered me a little because I was so insistent on finding an answer. Most children are curious about what makes them how they are. I went to my mom and asked, "Why am I different? I have so many people around me with arms..." From what I saw, I was the only one who didn't have them.

It was a devastating time—especially for my mom. My parents had no idea I was going to be born with a birth defect. She actually had a normal pregnancy and she was excited I was going to be her first girl. Most of the time, it's more [shocking] for the parents than the kid because the child doesn't know anything different. This is my normal and I've grown up to accept it.

MC: Did you opt for prosthetic arms at all?

JC: I wore them for 11 years. They became part of my everyday routine: I would put them on just like a jacket (or football equipment) and go to school. I was very patient with them and therapy, but I didn't like them. My mom knew I didn't like wearing them, but she heard from the specialist that I needed to grow into [the prosthetics] while I was young. Doctors would say that if I didn't learn to use them while I was younger, there was no chance I'd be able to use them as an adult. They had to make sure the option was available to me.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Come eighth grade—age 14—I got rid of them.

MC: Why did you ultimately decide to give them up?

JC: It's hard for me to explain this to someone with arms—you can't imagine anything different. Because I was born this way, [everything] felt more natural to do with my feet. Plus, there's nothing like the sensation of feeling things with flesh and bone. Prosthetics just felt very foreign to me: You wear them on your shoulders, strap them to your chest, and they're heavy and uncomfortable. If someone gave you a hug, you'd miss that touch. They were more like a cage for me.

MC: I watched this video of you playing the piano, eating with chopsticks, typing on a keyboard—all with your feet. Just how did you train yourself to do all these seemingly "normal" things?

JC: I don't look at it as training—it's more like adapting, as would a 3-year-old learning to trace letters in a preschool class. Just as anyone learns through their childhood during their stages of development, I went through the normal stages. There was a bit of a delay learning how to crawl [and walk] because most toddlers use their arms to grab furniture to pull themselves up. I went threw therapy to learn how to walk, and I probably started [walking] two to three months later than the average toddler.

MC: What about dressing yourself?

JC: Oh yes. Getting dressed is quite the process—I always say that's the most difficult physical task for someone without arms. Getting a shirt on wasn't a big deal, but getting pants and underwear on was more of a process as a kid. I went through 10 or 11 years of figuring out what system would work. I use a hook that suctions on the wall, like the ones on doors to hang clothes except lower on the wall, so that I could wiggle my way into my pants. The suction cup allows me to take it everywhere I go.

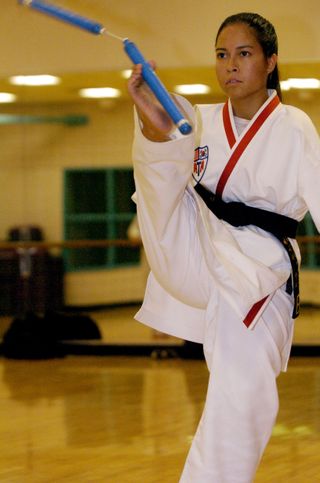

MC: Basically, you kick ass at life—and physically as a black belt. Why did you want to start practicing tae kwon do?

JC: When I was 10, my mom enrolled me and my brother and sister in tae kwon do because she thought it'd be a phenomenal way to have us do something together as a family. Also, I tended to take out my anger and frustration in kicks—and unfortunately, my siblings were the targets. My mom had to put me into something that would channel [my emotions] in a very positive way, and according to my brother, it really did help.

I had envisioned myself getting that black belt, and four years later I got my first on in the International Taekwon-Do Federation. I stopped for a while and picked it up again in college. I rejoined a school and club and earned my second black belt in [American Taekwondo Association (ATA)]. I've been practicing since that sophomore year in college back in 2002 and I am now a third-degree black belt in the ATA.

MC: So now I know never to pick a fight with you. What about being the first person without arms to fly a plane? You have to admit that's pretty awesome.

JC: If you would've asked me about getting a pilot's license before 2005, I'd say you were crazy. After I graduated college, a fighter pilot asked me if I wanted to go up on a flight in a single-engine plane. I always had a fear about being in an airplane, but I took this opportunity to go up on my first flight in a single-engine rather than a big commercial plane I was accustomed to. I was hooked and made a commitment to become a pilot. I wanted to motivate others to not let fear stand in the way of their opportunities.

MC: What exactly were you so afraid of though?

JC: Well, it was losing contact with the ground—not heights. I've always been a daredevil—I loved climbing and looking down from new heights. But maybe it was that lack of control you have [when you're in the air]. I shortly learned that if you can fly an airplane competently, you can fly it safely even if something does happen.

It's hard for me to explain this to someone with arms—you can't imagine anything different.

MC: On your website, it says, "It took three states, four airplanes, two flight instructors and a discouraging year to find the right aircraft." Why did it take so long?

JC: Not only was it an emotional fear, which didn't stop me, but it was more of a logistical challenge. Airplanes are not designed to be flown with your feet. I fly an Ercoupe—it's the only one that doesn't have rudder pedals—and it's NOT an airplane that's been modified by me—it wasn't specially built for me.

It's a standard Ercoupe that's 75 years old. It worked out that this was my fit. Because it was so old, it took an in-depth search to find this type of plane. It needed to be owned by someone—eventually I found Parrish Traweek—who'd train me but also who had insurance to allow me to be one of their students.

MC: What's it like to actually be in the air?

JC: That takeoff isn't scary at all—just the landing. Once you're in the air, you feel that sense of freedom of no limits.

When I'm not stalking future-but-never-going-to-happen husbands on Facebook, you can catch me eating at one of NYC's B-rated or below dining establishments—A-rated restaurants are for basics. Fun fact: Bloody Marys got me into eating celery on the regular. And for your safety, please do not disturb before 10 a.m. or coffee, whichever comes first.

-

Sources Close to Kylie Jenner and Timothée Chalamet Are Finally Addressing Those Baby Rumors

Sources Close to Kylie Jenner and Timothée Chalamet Are Finally Addressing Those Baby RumorsThe gossip surrounding the famous couple has hit a fever pitch.

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Emma Stone Says She Wants to Be Known By Her Birth Name from Now On—Not Emma, Her Stage Name

Emma Stone Says She Wants to Be Known By Her Birth Name from Now On—Not Emma, Her Stage Name“That would be so nice.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Anya Taylor-Joy's Chocolate Corset Gown Looks So Rich

Anya Taylor-Joy's Chocolate Corset Gown Looks So RichAnd those Tiffany jewels?!

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

The Best Bollywood Movies of 2023 (So Far)

The Best Bollywood Movies of 2023 (So Far)Including one that just might fill the Riverdale-shaped hole in your heart.

By Andrea Park Published

-

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ 2023: Everything We Know

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ 2023: Everything We KnowCue up Mike Reno and Ann Wilson’s “Almost Paradise."

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

Who Is Gerry Turner, the ‘Golden Bachelor’?

Who Is Gerry Turner, the ‘Golden Bachelor’?The Indiana native is the first senior citizen to join Bachelor Nation.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

‘Virgin River’ Season 6: Everything We Know

‘Virgin River’ Season 6: Everything We KnowHere's everything we know on the upcoming episodes.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

The 60 Best Musical Movies of All Time

The 60 Best Musical Movies of All TimeAll the dance numbers! All the show tunes!

By Amanda Mitchell Last updated

-

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We KnowNetflix owes us answers after that ending.

By Zoe Guy Last updated

-

35 Nude Movies With Porn-Level Nudity

35 Nude Movies With Porn-Level NudityLots of steamy nudity ahead.

By Kayleigh Roberts Last updated

-

The Cast of 'The Crown' Season 5: Your Guide

The Cast of 'The Crown' Season 5: Your GuideThe Mountbatten-Windsors have been recast—again.

By Andrea Park Published